Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOn Not Knowing America

A Kaleidoscopic and Highly Imaginative View of New York by One Who Has Never Visited It

HAROLD NICOLSON

THERE is a tiresome story somewhere about John Stuart Mill. I think it was John Stuart Mill, though it may have been Ruskin, or even Spencer, or perhaps Matthew Arnold. It was someone, in any case, who took his education and his mission seriously. This person had a way, when he purchased or was sent a book, of going on a solitary walk and considering what, before he had read the book, he then knew about the subject of which the book treated. The book, let us say, was entitled With Rod and Gun in Patagonia. John Stuart Mill (I feel sure somehow that it was John Stuart Mill) would walk among the laurels thinking all that he could think about rods, and guns, and Patagonia. He summoned from the recesses of that encyclopedic brain odd bits of stuff and fluff on all these three subjects, and then, thus clarified, he would return to the study, light the green lamp, adjust his spectacles, and read the book. On finishing the work, he would compare, or, as he would himself have said, "confront", what he had known on these subjects before he read the book with what he knew of these subjects after the book had been read, annotated, criticized and digested.

THE difference, he records, between the two stages of awareness was often very great. He recommended the system to other students. This recommendation reached me when I was at Oxford. I would be told by my tutor that I must read Stubbs' article on the three fields system. I obtained the article from the library. Without so much as a look at its contents, I rode around Port Meadow thinking hard of Dr. Stubbs and of the three fields system. What, before opening his article, did I know of these subjects? The answer, I regret to state, was "Nothing at all." The answer, after I had read the essay, was much the same. But the experiment had proved interesting. I have often experimented since. "What," I now say to myself, "do you know about America now that you do not know about America?" The answer, unlike that returned to Dr. Stubbs, is "A great deal." Nearer and nearer comes the eventful day, when I also shall land in America. What do I know about that landing? I know it, and of it, in every detail. There is nothing in my prefigurement of that vital and I trust impending event which is either vague to me, or inaccurate. I shall now place it on record. You shall see for yourselves how vivid, how penetrating, how sensitive are my first impressions of the great and illiberal continent which I have never seen.

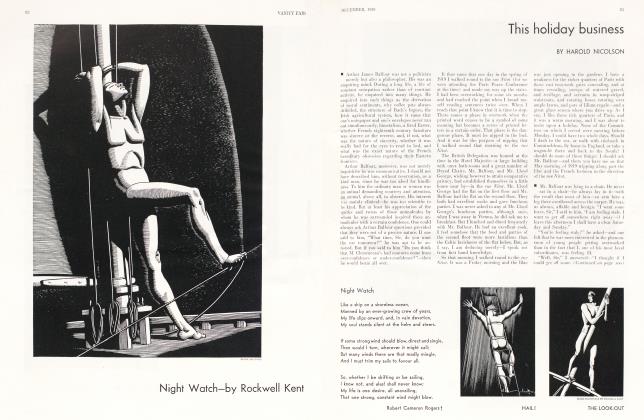

I SHALL cross, I think, upon the Ile de France. A pretty name, I feel, and a pretty steamer. There is a gymnasium on board with electric horses and a swimming bath, and one is allowed Medoc for luncheon free of charge. Besides I like the French, their cooking, their exotic flavour, and the way they allow one to break all the rules. Yes, I shall cross by the Ile de France, embarking at Southampton, I suppose, and thus avoiding any very abrupt severance from my native island. The prow of the steamer will point westwards, north-westwards. It will plough its way through large dark waves, carefully avoiding icebergs. There will be a wireless from which one will pick up French propaganda for a while; and then English folktunes; and then, an exciting moment this, the first notes of American uplift.

I shall read German novels in order to annoy the Captain and French novels to annoy my fellow-countrymen, and American novels to enlarge my mind. I shall sleep and eat, and ride on the electric horse. I shall walk round the deck in rubber shoes, and in rubber shoes I shall walk back again. And then again around. I shall tap French barometers. I shall have Dubonnet before dinner, and after dinner I shall have Cordiale Medoc. The click of my typewriter will be heard in the saloon.

This will last for five whole days. A feeling of expectancy will then descend upon the company and we shall shortly afterwards sight Sandy Hook. I shall be impressed by this, and shall gaze over the taffrail, gaze westwards, at a low smirch of coastline,—a lighter line against the lumbering sea, a darker line against the grey but lightening clouds. I shall be filled with appropriate emotions. "This," I shall say, "is the United States."—"Are the United States," I shall correct, being particular about such things, and on this momentous occasion anxious not to offend in any way.

Thereafter will come a flurry throughout the ship. Deck stewards walking about with a scrutinizing expression with drinkchits in their hands. Middle-deck-stewards totting accounts. Cabin-stewards being officious. Saloon and bar-stewards ostentatiously locking up drinks. They will come and take from me that little flask of cognac which I had bought at Cherbourg. There will be several hurried weddings taking place on board, and sweet champagne will be drunk in the deck-parlour. A sense of discipline and control will descend upon us: we shall think of our past life, and, finding it not altogether blameless, we shall throw from the port-hole such objects as may evoke suspicion or distrust. Proust, Lawrence, Joyce, Benedictine, the Manuscript of this present article, those silly pyjamas which I bought at Viareggio, my presentation copy of Trotzky's memoirs— all these will follow each other into the bracing waves of the off-shore Atlantic. Saddened but immune, I shall reappear on deck. The Statue of Liberty, dominating Ellis Island, will emerge from the mist, holding in its hand the torch of rectitude. I shall feel wdcked and small. I shall go back to my cabin and cast into the waters a translation of the Greek Anthology.

BY then the incomparable outline of New York will have appeared, like slits of cheese, upon the sky line. "That," I shall say, "is the Woolworth Building, and that the Times." It will be at this stage that, observing several motor launches rollicking out towards the steamer, I shall begin to bother about reporters. Supposing that they ask me, supposing—a far more awful thought —that they know—about my past life? That time in Constantinople for instance? Supposing that they ask me why I have come to America, what I think of prohibition, and Al Smith, and Miss Edith Sitwell? Supposing that they ask me about politics? Supposing that they mistake me for Beverly Nichols? Or for Mr. G. K. Chesterton? Or Dean Inge? Supposing (and this is a terrible supposition) that they pay no attention to me at all?

I retire to my cabin, to my state-room. I rehearse the impending encounter. American reporters, I have been told, must be treated as man to man. "Well, boys," . . . that's how I have got to begin. That was the way that Count Bernstorff always began. "Well, boys, here I am, and fire away." "Fire away," is it? or "Fire ahead"? The latter would be better, it is a mistake to begin being American at the start. I sit there, pondering on these things, being brisk with myself, avoiding all appearance in my rehearsal of that English drawl which so offends the impatient American brain. "Well boys, see here, I'm not what you might call . . ." Yes, that is much better. A tap at my cabin door. "Vous ne descendez pas, Monsieur? Voici une demi-heure que nous sommes déjà atterres" At that I collect my luggage and go ashore.

(Continued on page 102)

(Continued from page 55)

Quays are the same in any country. One descends upon them from an inclined plane. In America, however, the gangway is floored in India-rubber, —a pleasant pattern in green and white. The quay itself is carpeted in a pleasant shade of moss-green. There are palms and azaleas in tubs along the alley that leads to the custom shed. The custom shed itself is a fine building in green marble, an exact copy of the Propylaea at Athens. It is with"great diffidence, in order to avoid the reporters, that I advance towards the shed. I am told ("Say Guy . . ." my name is not Guy but I like the intimacy of it all), I am told that I must draw lots for the man who is to inspect my luggage.

I am amused at this, feeling it a gay thing to embark when disembarking on an element of chance. There is a large roulette board at the entrance made of gold and ivory and it is by this method that one chooses the man who will pass one through. My lot falls to a nice old man in a black peaked cap, and as we walk together towards the luggagecounters he tells me how quickly they do things in America, and how his second daughter had just got a doctorate of nursing, and how much he liked the Bridge of San Luis Rey. From time to time I glance at my luggage. It is still there. My friend— he has been telling me how slowly we do things in England, has also noticed the things. He rushes panting towards them: drawing a platinum and sapphire pencil from his pocket, he signs his full name upon the labels which they bear. A nice man, and what is more, well-educated. When I emerge from the custom house, the lights are already beginning to twinkle and flash. I find a motor cab. Eluding the reporters, who were hiding, I presume, at the back of the building, I give the address of my hotel. My breath is taken from me while, for a good hundred yards, my taxi dashes along the road. He then stops—there is a red light hanging somewhat dolefully above us.

It is long past seven when, through streets at one moment immobile and at the next lashed to furious action, we reach my hotel. The swing doors gyrate to the white cotton gloves of coloured page boys; my bag, or I suppose it would be bags, disappear for the moment in the white cotton gloves of hotel porters; my hand is clasped in the warm hand of the Belgian who directs the hotel. A blast as of a furnace strikes me as I pass the rubber plants and palms of the outer hall, into the vast onyx cathedral of the inner vestibule. I proceed to the desk. I am ignored. I bleat a little remark: "Please," I say, "I think I engaged a ..." I am ignored. Those friendly cotton gloves have gone. "Please ..." I bleat again. I am ig. nored. Already a slight heat-rash is appearing on my flushed cheek. "Say, Guy ..." I exclaim in a sudden voice, a very sudden voice. The man turns towards me and is very polite. After explaining how quickly, etc., etc., he asks whether I want anything. I say I want a room and have engaged one. He shouts a number, and from the recesses of the furnace appear more white cotton gloves and I am rushed towards a machine. It makes a noise, and in fact behaves, like a pneumatic tube. "Ouf," it says, and I am at once on the fortieth floor, in a smaller furnace, enlivened with Rose Dubarry silk. Three telephones stand upon the table. A large glass jug of iced water stands beside the bed. There is a chute in the door through which I chute my shoes down forty flights into the basement. A door on the right hand leads to a tiled bathroom in case I want a bath; a dooi on the left hand leads to another tiled bath-room in case I want two baths, The floor-waiter appears and tells me with a strong Norwegian accent that it is difficult at first to understand how quickly, etc., etc., and I ask for my luggage.

Forty minutes later my suit-case arrives. Poor battered, harassed little thing. The telephone rings. Damn these reporters! I answer it and am asked whether I am Alfred G. Morrow. I stand at the window watching the sky-signs. The telephone rings again. It is the Daily News.

"Well boy," I say quickly, "and what can I do for you?" "Is that Mr. G. B. Loedgman?" I reply that of course it isn't. "Sorry! ring off." I have a bath. Steam issues from the tap, and the cold tap is in itself a geyser. I sit and wait. The hot pipes sizzle softly, and as the over-head railway flounders past in the canon below me, the ice in my jug tinkles softly against the glass. I am depressed and lonely. There is no doubt about it, I should welcome, I should warmly welcome, even a reporter. The telephone rings again. It is really me they want this time. It is Bill Struthers whom I have not met since Persia. He is delighted; I am delighted; he will come round and fetch me. We are all going somewhere that I can't catch. "Hurry up," he says, "none of your beastly British loitering." I hurry up. It is then seven-fifty and I shall easily be dressed by eight. At nine-thirty Bill bursts panting into my room. "Now hurry up you slacker, we haven't a moment to lose." The rest of my first evening In New York, the very pleasant time I thereafter spent in that large but comfortable city, is not yet recorded. Besides I don't care for late hours, and it is time that I allowed my frenzied picturing to subside. Cold grey stars, as I look out from my window, above a little circle of shivering pines.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now