Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

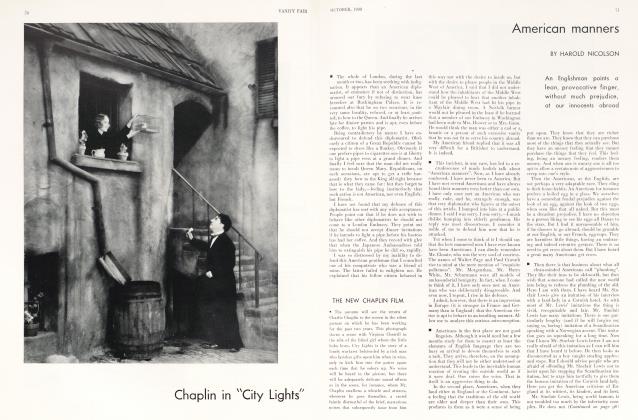

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWilliam T. Tilden II a genius of the tennis courts

William T. Tilden II is an undisputed genius of the tennis court.

Genius is a difficult quality to control, whether it is in a poet, surgeon, politician, or tennis player. Like most outstanding qualities, it usually irritates and antagonizes the people who do not possess it. They should be more generous. They need not be entirely approving in their attitude but they can cultivate a receptive attitude toward genius, one which forgives its faults for the sake of its virtues.

Am I wrong in saying that it is the tendency of most of us to make the way of genius a hard one? To criticize, with just a touch of bitterness, the manifestations of genius, to emphasize its failings rather than its virtues?

William T. Tilden II possesses the magic quality of genius which sets him apart from other tennis players. He is the outstanding figure of the tennis world today. No one need tell us this. Those who understand tennis, and who are old enough to have seen the beginnings of the game, when it was played by an earlier generation, say that Tilden is the greatest player of all time. There is no reason why we should not believe this.

But what has he done for tennis?

One often hears, from over-fastidious critics the same comments on him, endlessly repeated . . . "He has had his own way in tennis for the last ten years," "He has run every tournament he has played in," "He has run the Tennis Association—although it has pretended it has been running him," "He has questioned the decision of linesmen and umpires," "He never goes to tennis dinners," "Once he upset the Davis Cup play," and so on. I've heard them all. They all irritate me very much.

Because he has been, for so long, a tennis leader, there are many people, who, on principle, like to believe the uncomplimentary things they hear about him. We all know people who want the icing on somebody else's cake to be bitter.

But has Tilden always had his own way? Probably no more than he has deserved to have, being the leading tennis player of the world. Excellence will have its reward. Constantly in the public eye, he has become a victim of the inevitable popular suspicion of the world's favourites.

It is true that he has been accorded privileges not given to the rank and file of tennis players, but this is a natural result of his excellence in sport. But he has never (and I can say this as one who knows the character of Tilden well) accepted an advantage which would be in the least unfair to his adversary, or to any other player.

He refuses to go to tennis dinners. But is that such a great fault? Perhaps Tilden follows a certain schedule which bars late, long, or rich dinners. Perhaps officials' speeches, sometimes saccharine with phrases concerning exalted sportsmanship, bore him.

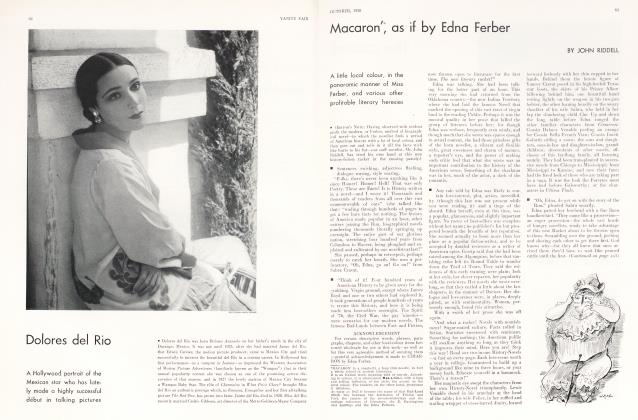

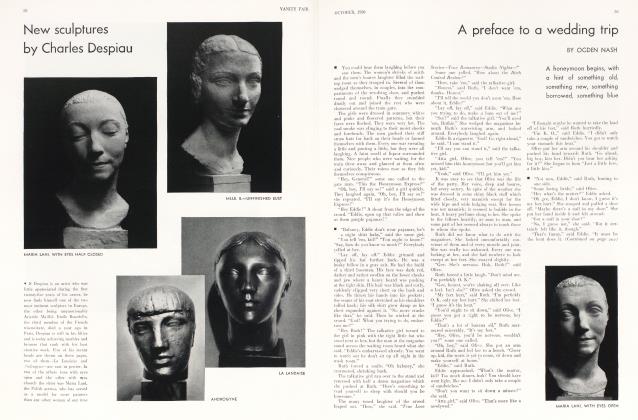

HELEN WILLS

And what about Tilden and his difficulty with the United States Lawn Tennis Association? Tilden is an individualist whose conduct is perhaps a little coloured by the erratic quality of every genius. He was brought before a row of middle-aged and stern officials to be judged upon the question of whether he was a professional or an amateur tennis player. Perhaps he felt that they were over-serious. Perhaps lie decided that they were too pompous in their interpretation of the rules. Perhaps he felt that their eyes were so intent upon the rules that they failed to recognize the true spirit of tennis as a sport. Perhaps he became so impatient with them that he was irresistibly impelled to break some of the many rules which they had made.

Again! He is irritated by linesmen! Terrible thought! I have watched Tilden play in hundreds of matches, and have seen him sometimes look at linesmen in no uncertain terms—but—(and this is the important point)—no more for himself than for his opponent. He will question a decision that concerns his opponent as quickly as one that afTects himself. He makes his demands for himself and opponents alike. His dramatic and imperious gestures are a part of his nature. He cannot behave otherwise than dramatically upon the court. His generosity and his fairness to his adversary are quite beyond question.

What has Tilden done for tennis? What he has done is beyond estimating—and beyond compensation. First of all, what is his record?

His name appeared in the first ten of the National Tennis Ranking as early as 1918, —being ranked second. The next year he again ranked number two. The next year he stepped into first position, and since 1920 has been first among all American tennis players. For ten years lie has been the leader! Ten years is an eternity in sport. During that time he has shown how tennis should be played—in a beautiful style with finished and masterly strokes. He has shown how perfectly speed, tactics and style can be combined. We are safe in saying that no other player has so ably included all of these in his game. There have been players who overwhelmed with their speed, there have been others who were master strategists—but there has never been another to equal Tilden in the combination of all the qualities which go to make up the ideal tennis champion.

During the ten years that Tilden has been at the height of his career, he has played not only in the National events—Davis Cup and International meetings—but in countless tournaments and exhibition matches as well. In Europe his skill and his example have inspired the tennis players of four countries. He has encouraged hundreds of young players throughout the country. Thousands upon thousands of people have watched him play, have marvelled at his display of graceful stroking, have seen how the game can be played by a genius. Those who were learning, went home with a better idea of how to execute their own strokes. And last, but far from least, these thousands have derived a definite and an almost inspired pleasure from seeing him in action on the court. The endless hours of enjoyment which his tennis has brought to the multitudes who have seen him play, is beyond computation.

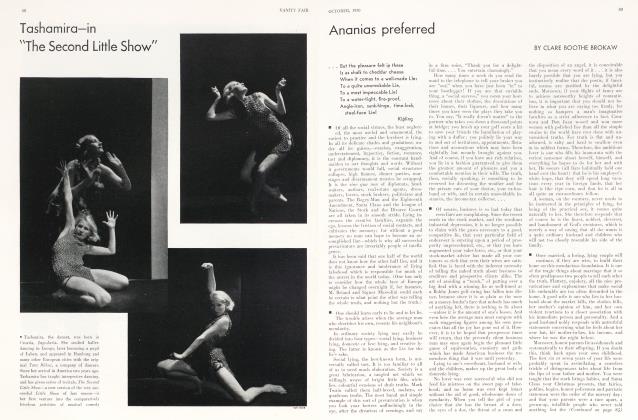

Long, thin Tilden, with his burning, deepset eyes, his delicate and slender fingers, his over broad shoulders, his wisps of straight, dark hair, his little mannerism of twitching at his left sleeve with his right hand, his way of leaning his head on one side and snapping his fingers at a bad shot—all these one remembers. Never in repose, always supercharged with nervous energy, Tilden is as restless as the sea-waves, a creature of constant activity, and endless change.

If the game of tennis had not happened to engage Tilden's attention, what would have happened then? Well, I am somehow convinced that his genius would have shone in some other field; for it is genius that produces perfect craftsmanship, not craftsmanship that produces genius. And it is certainly fair to assume that genius like Tilden's is a quality that dominates whatever material it has been given to work with.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now