Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

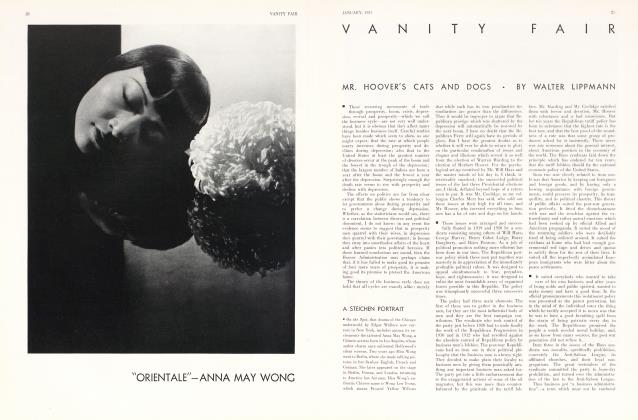

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Theatre

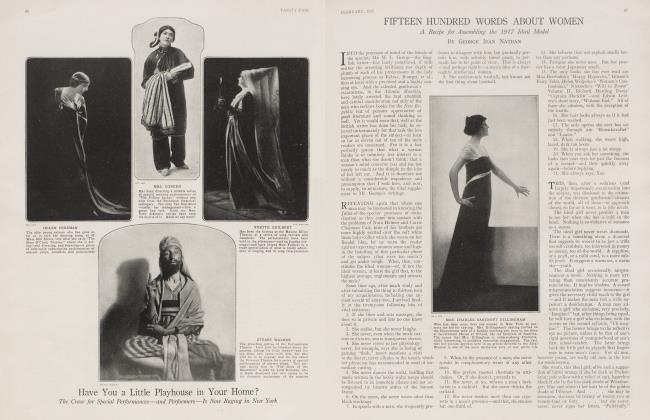

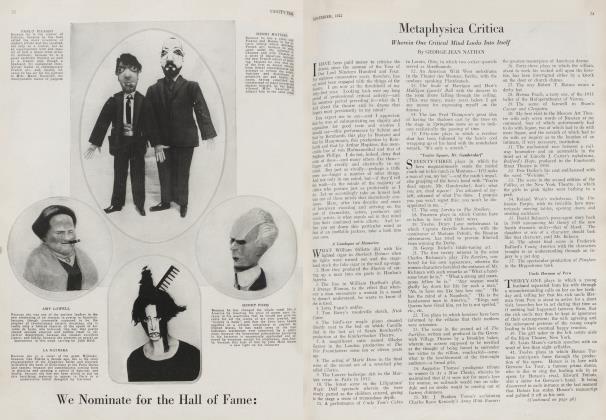

George Jean Nathan

■ THE THEATRE GUILD.—It is all very well to say that the Theatre Guild has been producing some pretty indifferent plays in the last few months—and. accordingly, I duly say it—but just where it would find very much better ones, I for one do not know. True enough, it has in its possession Alfred Savoir's Lui, which is infinitely better than Roar China!, with which it saw fit to introduce its season, and also Maurice Donnay's paraphrase of Lysistrata, which is not only superior to Elizabeth, the Queen, its second production, but even more greatly superior to the version of Aristophanes currently on view in another part of town. But, aside from these two manuscripts, I suppose that, things being what they are, it is doing just about as well as it can do. For the sad truth is that never before within the period of my memory has there been, in America as in Europe, so great a shortage of reputable dramatic writing. If the Guild is this year not doing the kind of plays one has a right to expect of it—well, no more is anyone else. The simple fact is that, save for a few plays that have already been gobbled up, that kind of play is not being written.

Roar China!, by a Russian michaelgold named Tretiakov, is a crude propaganda bomb fashioned in a Moscow cellar out of a German Expressionist cigar box and some Drury Lane scenery, and loaded with seltzer bottle carbonic acid which the author, in darkness, has mistaken for nitroglycerine. Essaying to arouse indignation over the European and American exploitation of China to selfish ends, with a general reflection upon the oppressed of the earth, it is so immoderately indignant that it misses all effect. Every child, when first he has learned to play the piano, plays everything, whatever its nature, with has foot glued to the loud pedal. So the amateur in drama confuses unremitting vibration and noise with projective power, hiding his lack of virtuosity in a nervous and arbitrary racket. Tretiakov, at every turn, confounds perspiration with persuasion. He waves red flags, shoots off guns, throws idealistic epileptic fits, sets of! giant fire-crackers, yells, screams, shouts, gesticulates and otherwise so greatly substitutes a theatrical hydrophobia for authentic drama that, when the evening is done, one has the feeling that one has seen a play acted less by a troupe of actors than by a troupe of stage directors who are excessively angry with them. Russia, since the Soviet regime, has disgorged a lot of such stuff as Roar China!, none of it, as art or even as approximate drama, worth the laughter to blow it up. The mass of it closely resembles the kind of theatrical hullaballoo that concerned itself with denunciations of militarism in war-time Germany, save that it substitutes indignations against capital and an apotheosis of the humble worker for indignations against the monarchical impulses behind slaughter and an apotheosis of Miss Democracy, and, further, that it is immensely inferior on all counts in dramaturgic skill.

That propaganda, if handled by an artist, may not conceivably have a place in drama, I am not too certain. There have been propaganda plays written by artists that have, for all the critical superstitions and by-laws, been meritorious. But, since artists are few and far between, the propaganda drama by and large amounts to little more than the miscegenation of stage and soap-box, with a dull little fevered bastard as offspring. Such plays as Tretiakov's are weasel drama in the disguise of a ferocious bull. And, since art has no share in them, their snorts and roars frighten and convince no one.

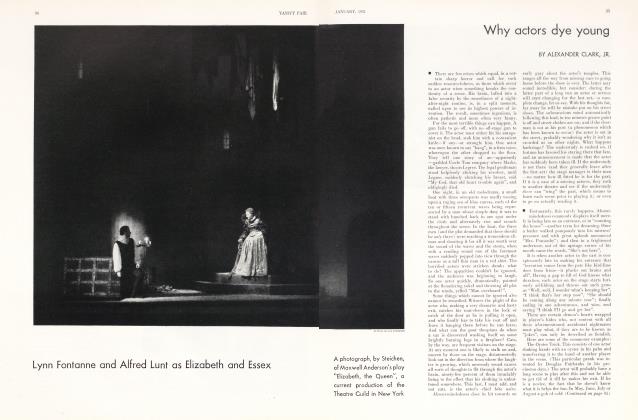

Elizabeth, the Queen, by Maxwell Anderson, though it leaves much to be desired, is in a class apart from the mad Tretiakov frothing. It aims at dignity with an honest, if not always sufficient, talent and it has enough respect for drama not to boss it obstreperously off-stage and wheel out, in its stead, a gigantic papier-mache hand with a threatening finger pointed at the audience. If it does not achieve its purpose, it is simply because the historical drama seldom does, save its fabricator be a poet so eloquent that he can make his auditors largely oblivious of the fact that the drama has anything at all to do with history. History, or at least an apocryphal version of it, gets in Mr. Anderson's way too often and interposes itself between what gift for poetry he has and the necessary audience remission of historical consciousness. He often writes gracefully and sometimes beautifully, but it requires a steadier and more consistent beauty of craftsmanship ever to make an audience agreeably forget that, for all the occasional beauty of word and line, it is still looking at some very funny actors' knees in red tights, some disturbingly tin spears, a lot of excessively stagey armor worn by actors who got a shave and hair-cut that afternoon at the Hotel Astor, and a very evidently Jewish young man passing himself off as Francis Bacon.

• Dealing with the oft-told tale of Elizabeth and Essex, Mr. Anderson builds his periodically paraphrased play around the single episode of the Ireland campaign, using that episode as a focus for the passions of his central figures. His first act is the best of the three; the second is dull and halting; and the third, in the tower chamber before the execution, resolves itself into little more than a Flavia-Rassendyl hokum scene of leavetaking, with Flavia made up in a red wig and talking throatily of England and government instead of wistfully about Zenda and the moon. But while Elizabeth, the Queen in the aggregate snaps Strachey with a dollar kodak, it has its moments nevertheless. It fails, when it does fail, without shoddy. Its fault is that, while it occasionally interests, it does not excite. Nor does it glow. And without those qualities, historical drama collapses.

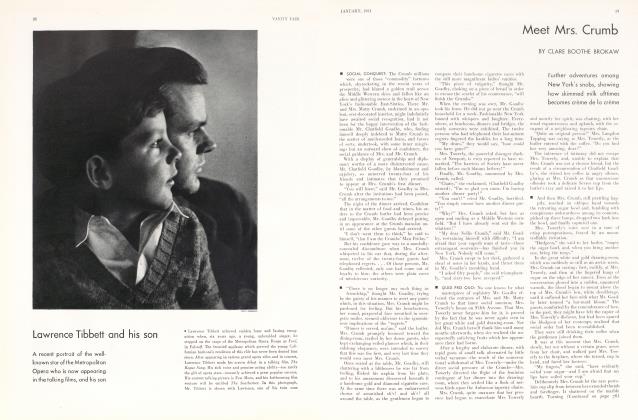

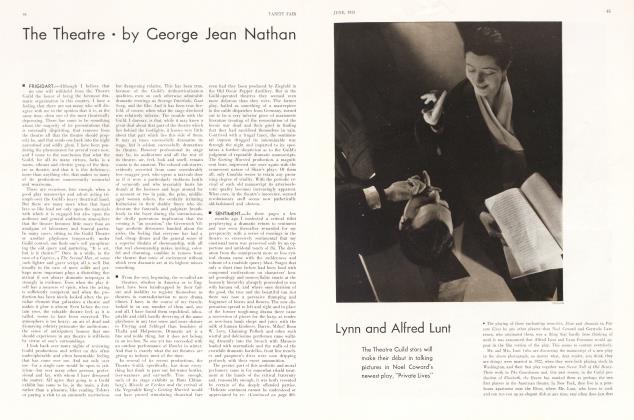

Miss Lynn Fontanne gives an excellent performance of Elizabeth; she grows in stature as an actress year by year. Gradually she has lost that bony histrionic quality, that modern-day British penchant for acting with the neck and that habit of using her voice as if it were a ukelele which, in combination, calloused her earlier work. Alfred Lunt's Essex, on the contrary, is a surprisingly slipshod job. This best of our younger actors on this occasion gets no closer to his role than his costume and, in addition, brings to the reading of his lines a pronunciation and enunciation so garbled and slovenly that the impression is infinitely less of Essex than of Essex Street.

MUSICAL PLAYS.—It may or may not be a lamentable fact and one that reflects either upon the deficiencies of the present-day drama or upon the deficiencies of the kind of people I happen to know, but it remains that whenever I invite anyone to go to the theatre with me these days, the first thing that personasks is, "Is it a musical show?" If the answer is no, the person seems suddenly to remember that he has a very important engagement for that evening or promptly contrives to manufacture an imitation of an ominous cough which, he observes, indicates that he is on the verge of pneumonia and hence must go right home and to bed. The moment a new musical show is announced. I notice that men who have not given me so much as a passing thought for months suddenly metamorphose themselves into warm and lifelong old cronies who jump to the telephone, assure me how much they have missed me, inquire dolefully why it is that we do not see more of each other, and then with poorly concealed casualness ask whether I have anything to do that evening.

That many of the musical shows are not much good and that these gentlemen are fully privy to the fact does not dissuade them from solicitousness over the state of my friendship for them. Any musical show will do. And, as a critic given notoriously to a wholesouled admiration of dramatic art, I am sorry to have to confess that I understand their preference perfectly. At even the poorest musical exhibit, one stands a better gambling chance of amusement than at the average play that the theatre presently uncovers. Having been put upon by so many playsmany of them over-courteously, shamelessly and easily let down in the newspaper reviews—, that small share of the public that 1 happen personally to know (and that you yourself doubtless know in turn) cares no longer to risk an evening in the dramatic theatre and would much rather take a chance on low comedians, dancing girls, some bright colors and music of one sort or another. Once in a while, the taste is proved to be sound, as, for example, in such a revue as Three s a Crowd, for there is more genuine entertainment in a single show of that kind than the theatregoer can find in a whole season, constituted like this one, of plays like Dancing Partner, Suspense, Through the Night, Cafe, That's the Woman, The Long Road, Insult, The Rhapsody, With Privileges, Symphony in Two Flats, The Cinderelative, Frankie and johnny, Roadside, Stepdaughters of War, Marigold, Solid South, Blind Mice, London Calling, Pagan Lady, Sisters of the Chorus, This One Man, Sweet Stranger, His Majesty's Car, Sweet Chariot, The Noble Experiment, Puppet Show, The Last Enemy, As Good as New, Room of Dreams, Mr. Samuel anti Made in France. And when 1 use the word entertainment in connection with such a show, 1 use it not in its idlest but in its best sense. Only punditical dunderheads discriminate in the employment and definition of the word in connection Avith a musical show as against a dramatic play. What entertains an intelligent man may be as soundly worthwhile in one direction as in the other. A dramatic play that merely entertains is no whit better, from any critical point of view, than a musical play that does the same thing. Drama must have more than merely that to earn its salt.

(Continued from page 30)

Three's a Crowd has intelligent humor, some of it pleasantly IOAV; it has some pretty good light satire; it has an editorial sense; it has some excellent dancing, one or two good tunes, some effective color and a nice leaven of irony. And though most of the other musicals lack at least one or two of these qualities, several of them still possess various features that make them a happy relief from the dull, lustreless, routine dramatic stages that spread to the left and right of them. Cole Porter's songs and lyrics in The New Yorkers, for example, provide an ingratiating humorous and satirical intelligence that the dramatic playgoer could not find in an entire season's output of the Hattons, Samuel Ruskin Golding, Frank Harvey, Daniel Coxe, Edgar Wallace, William Du Bois, Michael Kallesser and Michael Grismaijer. In addition there is more humor in the show itself than in any half dozen such straight comedies as Dancing Partner, Marigold or Sisters of the Chorus. In Ziegfeld's Smiles there is dancing by Marilyn Miller and the Astaires that comes very much nearer to being true art than all the bogus dramatic "art" in twenty or thirty such pseudo-serious affairs as This One Man, Insult or The Last Enemy. And there is more fun even in something second-rate like Sweet and Low than you'll find in any number of straight farces produced during a season.

As against shows of thi3 kind, of course, we have a due share of mush oratorios and it is these that plainly prejudice the more professorially minded against the species as a whole. We have, for example, things like The IF ell of Romance, with its lyrics persistently emphasizing the theory that money does not bring happiness and that love is the dream of dreams, with its old-time Lew Fields' comedy horse transformed into a cow, with its tale of the king disguised as a poor poet and of his wooing of the fair princess, with its soldier chorus huddled against the footlight trough and brandishing its swords on the last yelled note, and with its comedian named Otto von Sprudelwasser. We have, for further example, such things as Princess Charming, with the soldier chorus up to the same old business, with the proud Princess Elaine succumbing to the love entreaties of a handsome commoner, with lyrics of the "Palace of Dreams" species, with the princess disguising herself in boy's costume, with the same character pretending at another point that she is her own servant, and with the meek comedian—he is called Irving Huff in order that be may subsequently be mistaken for Ivanoff, the revolutionary desperado—bending himself in at the rear in anticipation of a kick every time he makes an exit.

Such exhibits fall under the head of what is dubbed romantic operetta, with boredom generally guaranteed save occasionally for a waltz pilfered from Vienna and a couple of new naughty jocularities. I cite another specimen. The scene: Peru. 8:40: Song by Pablo, fiercely mustached, "Pablo, I am Pablo, the gaucho mucho grando!" 8:50: Song by Jack Haines, the white-shirted, putteed American, "Fair Nina Rosa, pearl of Peru, I love you, I do." 9:00: Entrance of comedian with joke: "If there are any fleas around here, I'll get 'em. I got what they call in-sects appeal." 9:02: Entrance of Nina Rosa, passionately twirling her red skirt above her hips. Jumping astride a table, she sings, "With the dawn come dreams of you." 9:10: Love scene between Jack and Nina, with the ferociously jealous Pablo eavesdropping. "A rose for you, Monsieur," whispers Nina in somewhat dubious Peruvian, pressing the bloom to his nose. "I know nothing of roses," Avistfully replies the heroic Jack; "I am an engineer!" Following which he-man non sequitur, he beseeches a kiss. Nina Rosa sadly shakes her head. "Nina Rosa no kiss man till she marry." 9:15: Duet, "Your smiles, your tears," by Jack and Nina. 9:25: Re-entrance of comedian Avith joke about Texas Guinan. 9:40: Pablo, the ferocious, plots to make off with his rival. Jack. 9:45: Topical song by comedian No. 2: "Pizarro was a very narrow man." 9:55: A pair of specialty dancers, their act concluding with the man dancer throwing his Avotnan partner violently to the floor, thus indicating—when she gets up and resolicits his love—that Avomen admire masterful men. 10:05: Nina Rosa, in order to get the secret of the gold mine, pretends to desert Jack for Pablo. Jack beholding them in an embrace, believes his sweetheart is deceitful, proclaims his contempt of her in vociferous song and, tossing his head, declares defiantly that he is off to a party at Don Fernando's hacienda to drink and consort with loose women. Pablo issues a loud, sardonic chuckle. Nina Rosa, griefstricken, reaches out her arms imploringly to the departing Jack. End of Act I.

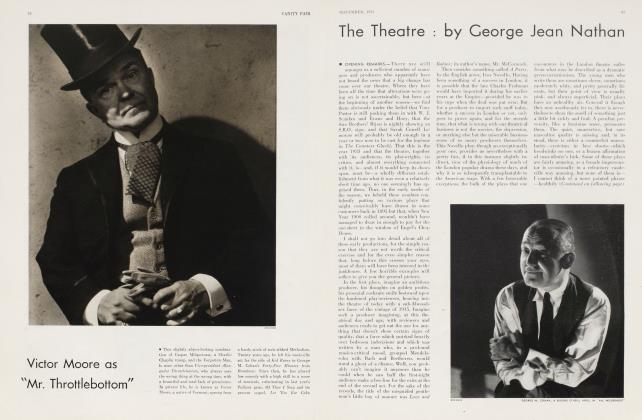

I trust it is not necessary for me to proceed. File Nina Rosa—that is its name this time—under the musical comedy N's. Aside from a brace of pleasant melodies by Romberg and a cute dancing girl billed simply and with an air of complete finality as Armida—like Michelangelo, Napoleon, Listerine and God—it follows Avithout deviation the stereotyped formula. As a contrast, we have Mr. Joe Cook's Fine and Dandy. Cook's idea of a musical show is to do as little as possible about a book and not much more about what, on Broadway, goes by the name of music, and to fill in the gaps between dancing numbers Avith comedy so low that one has to lie on the floor under one's seat to get a bird's-eye view of it. Each year he devises a repertoire of imbecility plus that guarantees laughter from the moment he comes on and displays a highly complex machine which, after intricate manipulation of its countless levers, gears and wheels and after a wealth of buzzing and whirring, projects a small dingus that scratches his back, to the moment—just before the last curtain—when he trips over himself and Dave Chasen and lands squat upon his ulterior embonpoint. NOAV that Victor Herbert is dead and Lehar an infrequent contributor to our music SIIOAV stage—and with Jerry Kern issuing forth only at rare intervals—such monkeyshines are a happy and very welcome substitute for the pretentious noises usually provided by their aspiring juniors. At any rate, the laughter they provoke is intentional.

AMERICA AND ENGLAND.—If Ave

may gain any wisdom from the statistics presented by the American theatre last year and during the season that is now approaching its half-distance mark, one point seems to stand out pretty clearly and that is that very, very seldom has our theatre use, any longer, for English plays, adapted plays that have been great successes in England, plays Avritten by Englishmen living over here or expatriated Americans living in England, dramatizations of English novels, or English musical comedies and revues. The English trademark, whatever the form of entertainment upon which it is pasted, seems—save in the rarest instances— to spell American disaster. Of the English importations last year, all the folloAving Avere failures: Murder on the Second Floor, Rope's End, Dear Old England, Many Waters, Scotland Yard, The Matriarch, The Middle Watch, Thunder in the Air, The Infinite Shoeblack, Lady Clara, Candle Light (an adaptation that bad run a year in London), Other Mens Wives (Avritten by an American Avho has made England his home), and the revue Wake Up and Dream. Bitter-Sweet, a comic operetta, failed to achieve anything like the success it had in its own country, where it is still playing after almost a year and a half, and The Apple Cart was saved only by the Theatre Guild's safe advance subscription policy. Of a total of eighteen importations made during the year in question, only three entertained the general American public sufficiently to do any trade at all. One of the three, The First Mrs. Fraser, did a good box-office trade. A second, Michael and Mary, enjoyed a run in a bandbox of a theatre holding only 298 persons. A third, Berkeley Square, Avritten by an American and an English actor who has been playing in America for many years, did only a moderately satisfactory business.

In the present season, up to the moment of writing, nine English plays, one adaptation that had been a great success in England, one dramatization of an English novel and one play written by an English actor at present residing in America have been displayed to the American public. Of these, instantaneous failures have been Suspense, Insult, Symphony in Two Flats, Nine Till Six, Stepdaughters of War, Mangold, London Calling, Canaries Sometimes Sing and The Last Enemy. Mrs. Moonlight has had a mild trade at the same little band-box that housed Michael and Mary last year; On the Spot seems to be doing business as I write; and the fate of The Man in Possession is still in the balance.

In other words, out of a grand total of thirty English importations of one kind or another, only four—the protected Guild offering excluded—may be definitely said to have paid even their expenses, Avith two others still guess-Avork so far as the local public taste may turn out.

What holds true in the case of the great majority of English plays, apparently also holds true of English actors. With every unusual exception, the American public has lost its taste for English actors to such a degree that their presence in the cast of one of the imported plays only hastens the failure of the latter. This prejudice, based upon reasons that I have hazarded in the past, has grown to such proportions that we find that when an English play infrequently succeeds in America it is almost invariably because American actors have been substituted for English in at least one or more of the leading roles. The First Mrs. Fraser had an American actress as its star; Michael and Mary had Americans cast for its two leading roles; Berkeley Square had American actors conspicuously figuring in its cast; and On the Spot is full of Americans. Mr. Miller will take no chances on his English importation, Petticoat Influence, and will cast an American actress in the leading part. The only English actor today pulling in any trade in America to speak of is George Arliss, and in order to do it he has had to sell his soul to the talkies.

If the plays Avhich I have tabulated bad been failures in England, the present report and deductions from the report would have no significance. But it must be remembered that they Avere, the overwhelming majority of them, successes there and hence refleeted the theatrical taste of our British cousins. That the tastes of the two countries are thus rapidly pulling farther and farther apart is becoming increasingly obvious;

(Continued on page 87)

(Continued from page 80)

Supplementary. ■— Another English importation, Art and Mrs. Bottle, by the author of A/r5. Moonlight, exhibited after I had written the above, shows no signs of achieving any success and will doubtless add itself to the catalogue of British failures. It is trivial and very feeble stuff and not for American theatre-goers. Hello, Paris! is a dismally dirty music show, featuring the depressing Mr. Chic Sale, author of The Specialist. The misguided friend who called me up and asked me to take him to it scooted out of the theatre and gruntingly deserted me half an hour after its curtain went up. Marseilles, a translation of Pagnol's Marius by Sidney Howard, lost in the Gilbert Miller production what modest virtues the original play

showed in its Paris presentation. Poorly acted and staged with a complete lack of atmosphere, it was made to disclose itself here as a semi-caricature of its author's work. That author, however and incidentally, is one of the most greatly overestimated, both in France and in this country, that we have engaged in a number of years. Grand Hotel, made by Vicki Baum out of her novel Menschen im Hotel, is an occasionally amusing but negligible cinematic account of thirty-odd hours' happenings in a Berlin Gasthaus. Played on a revolving stage and embellished with various mechanical tricks and didoes, it is the sort of thing that Reinhardt and other such German producers indulge themselves in by way of trying to make names for themselves at the expense of reputable drama. The local version is ably performed by a troupe including the Miles. Leontovich and Alden and the MM. Rumann, Jaffe and Hull.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now