Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

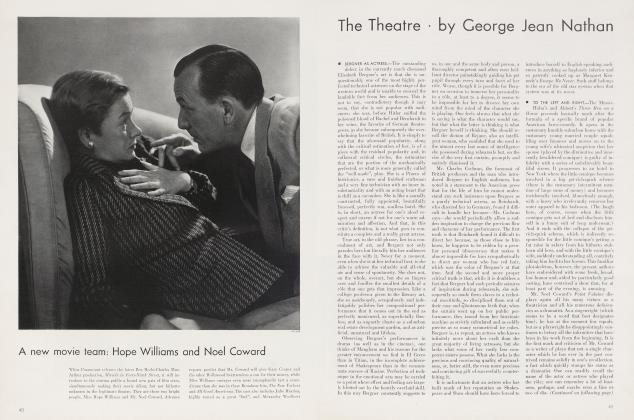

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Theatre

George Jean Nathan

PREAMBLE.—Sympathy with mere good intentions is, unfortunately, no business of the critic. I say unfortunately, because it seems too bad that criticism must at the moment continue its uncompromising course in the presence of applaudable intentions hamstrung through no fault of their own. I allude specifically to our producers. If ever there was a time in the American theatre when many of such gentlemen were ready and eager to do something worth-while for it, that time is now. No play of quality need wait for a production; no competent actor need be out of a job; in short, no opportunity for merit's immediate hearing has ever been so good. But where are the plays; where are the actors? Inasmuch as I am paid an extravagant honorarium to answer any and all such questions, whether I always know the answers or not, I shall proceed to expatiate.

There are, alas, hardly any plays of any real quality in sight; the sparse handful that there are have been quickly snapped up and are duly to be shown on the local stages by their happy impresarios. As a critic of the theatre, if not as a producer. in it, I have either seen or read the bulk of recent European manuscripts and, in the lot, if my judgment counts for anything, there are not more than a half dozen at most that even remotely approach the reputable, and these have already been pounced upon by one or another of our starved and hungry managers. Since January first of this year, I have also read one hundred and fifty-two play manuscripts by American authors, with a view to finding one good enough to include in a series of modern drama of which I am the editor, and nary a one—with the exception of O'Neill's Mourning Becomes Electra, already under contract to another publisher— have I laid eyes on. In this juncture, what can the producers do? They have to produce something in their theatres—despite the lofty contention of critics who, not being burdened with real estate mortgages, taxes and a ceased revenue, very aesthetically argue that it would be better if they didn't—and so they take hold of the best secondor third-rate stuff they can lay hands on and shamefacedly trust to God, Percy Hammond and the New York Title and Mortgage Co. to get by for the time being. The notion that these producers would not gladly produce better stuff if they could find it is a notion close to the fancy of reviewing fledglings, retired dramatic critics and other such idealists who vaguely imagine that it is always the fault of managers and producers when the theatre is not better than it is. The theatre at the moment isn't better than it is for the simple reason that there is nothing lying around for the managers and producers to make it better with.

It is the vain idea of the average dramatic critic that when a manager or producer telephones or writes to him bidding his suggestion as to a good play to produce, the manager or producer in question is simply trying to horn in on him privately and personally and work himself, through implied flattery, into his good graces. I can think of nothing more ridiculous. What the manager or producer is trying to do is simply to get track, if possible, of a good play. A critic is not and should not be a self-consciously grand creature locked in an ivory tower with a couple of bouncers standing guard over his aloof Corinthian elegance; he is and should be part and parcel of everything that may in any way conceivably help and improve the theatre and drama of his day. And as one such critic with a desire to do his modest share in that direction, all I can say is that, in answer to numerous recent prayers for suggestions as to good new plays, all that I have been able to tell the imploring gentlemen is that I'll be damned if I know of any.

In the matter of good actors, it appears to be the same. With so many of the younger talented ones selling themselves to the talking pictures, the producers are up against it when it comes to casting what plays they have. Most of the younger players who are not in Hollywood and are available to the producers are, with certain admirable and praiseworthy exceptions, not in Hollywood simply because they have not the necessary physical appeal and personalities to get the profitable Hollywood invitation, and so the theatre, taking them on willy-nilly, must contend with their lack of those very qualities that mean so much to the stage and to drama. The result is that the theatre, with the certain exceptions noted, finds its platforms for the time being inevitably occupied by young men and women completely without magnetism and glamour—and with very little skill to boot. It is a fact known to me personally that plans for the production of no less than eight plays have had to be abandoned because the producers could not obtain young players, now in the pictures, to do them and because the producers knew that to cast them with the lustreless players presently available would spell, and properly, their failure. And it is a second fact known to me personally that at least three meritorious plays about to be or recently revealed to local audiences have, to their producers' loud and agonized groaning, as a last resort been arbitrarily cast with players who give the producers a severe colic every time they think of or look at them.

The producers, in short, are not to blame for the prevailing state of affairs. One cannot make bricks without straw. Nor can one make a theatre without plays and players.

GUILD EXHIBIT NO. I.—This shortage in available actors is clearly perceptible in the instance of the Theatre Guild's production of Alfred Savoir's He. That the Guild made every effort, after its try-out of the production last Spring, to recast the play in one role at least with a more suitable figure is common gossip. But, finding the job impossible, there was nothing left for it to do but to let things stand as they were and grin and bear it. It is thus all very well for us critics to tell the Guild that the casting in this or that direction is deplorable, but the Guild itself knows it already and there is nothing it can or could do about it.

Savoir's comedy provides a very much more amusing theatrical evening than the average. One reads of it that it has—Deo gratias!, bellow some of the reviewers—an idea behind it, as if every play, whatever its quality, didn't have some kind of idea behind it. When reviewers use the word idea, however, they wish us to believe that the playwright has evolved out of his cerebrum a concept that tends toward the original and unusual in a metaphysical and philosophical direction. Thus, a creditable play with an idea behind it as substantial in another channel as, say, that of What Price Glory? is never catalogued by them as a play with an idea, whereas some such completely negligible exhibit as, say, Hotel Universe, with its juvenile gropings toward metaphysics, receives their imprimatur. The idea behind Savoir's play is the height of commonplaceness, even theatrical and dramatic commonplaceness, which is pretty much of a height. But as it gestures faintly in the direction of the transcendental, with undertones of a defective philosophy shrewdly concealed in wit, it is hailed as having something of an intellectual disposition, whereas a play like Payment Deferred, that has a basic idea, unpretentious as it is, at least equally profound, is politely dismissed as merely an interesting murder play.

(Continued on page 80)

(Continued from page 36)

The so-called idea behind Savoir's play is that each man's God lives only in his own particular prejudice. If this is an "idea" in the reviewers' minds, then what terminology would they employ for the thrice more original and philosophical idea behind some such confessed light comedy as Hermann Bahr's Kinder? The truth of the business is that the idea upon which Savoir has built his play is not only a banality but one which has already often served the theatre. But while that may he the truth of the business, it is hardly the point. For the point is that the idea does not matter. What matters—and here I simply merchant a very obvious platitude—is the way the playwright has treated the idea. His treatment is as fresh as his idea is stale. Substituting theatrical ingenuity for ingenious reasoning and some deft writing legerdemain for profound thinking, and glossing over his philosophical deficiencies with a very fair grade of wit and humor, Savoir has turned out a comedy flicked with satire that passes an evening very agreeably. And what more, in these dramatic hard times, should anyone ask?

THE IDEA CANCER.—This critical itch for ideas in plays, so assiduously urged upon our playwrights by the professors in the Sunday theatrical supplements, is doing more than its share toward the debilitation of American drama. Not content with the simple, artless but none the less sometimes worthy drama that has come from American hands, the critical gentry are covered with a prickly heat induced by the continued absence from it of what they call "ideas." Giving heed to their lamentations and injunctions, certain playwrights, otherwise talented, who have no more gift for the drama of ideas than a Frenchman has for beer-brewing, foolishly proceed to wreck what competences they have by proffering a species of mental pabulum that needs only a red apple for teacher to put it in its proper setting. Time and again, accordingly, we engage a playwright, who would have been quite all right if he had been left alone, making mock of his own especial skill by trying to live up to the ridiculous critical desires and demands. And time and again there is thus lost to our theatre a play that, in its own field, might have been pretty good but that has been botched out of merit because the author had been persuaded to try to make a bigger man of himself than he really was.

Philip Barry is a case in point. Having a pleasant little talent for pleasant little comedies, he has been sent by his admiring counselors on a detour toward the profounder drama of ideas and has not only forsaken the field of writing for which he is best equipped but has made something of a monkey of himself. There are several other cases as well, and Mr. George M. Cohan now finds himself one of them. No man writing for the American theatre has given it more entertainment than this same Mr. Cohan; no man has written more simply amusing comedies, farces, musical shows and revues. But now, having been led idiotically to believe that what the critics and their public want is not only amusement but something to make them think to boot, he has gone and turned pseudo-philosopher and thrown a wrench into himself. In his latest play. Friendship, he started out in the old entertaining Cohan manner, with easy humor, with that uncommonly dexterous theatrical chicane of which he is a past-master, and with laughter ready to spring out of every crack of his manuscript. But not long after his commendable beginning he began to get self-conscious after the prevailing dramatic mode and to feel that, if he were going to be in the swim and the good graces of the critical fraternity, he had better stop being merely very amusing, as in former years, and go in for a little moral philosophy or some other such intellectual delicatessen. So what did he do? He plunked himself down in a chair just as the audience was getting its money's worth all around, straightened his face, and started in to ratiocinate with a world of gravity on the cause and effect of modern materialism, the jesuitry of the younger generation, the ethics of this and that, and analogous matters that bored stiff all those of us who had had such a grand time at The Tavern, Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford, Seven Keys to Bald pate and his plays of other days.

Let us stop this nonsense about ideas in plays. Some of the very finest plays ever written have had no more ideas in them, in the current critical sense, than some of the very worst. The present trouble with the American drama is that too many of its authors are trying to write ideas instead of plays.

SEX AND INTELLIGENCE.—That the legitimate theatre has pretty well exhausted sex as a subject for intelligent interest—or even fair amusement interest—is becoming steadily more and more apparent. That sex still occupies so great a share of our playwrights' attention has no more to do with the truth of the observation than the fact that real estate owners are still putting up all kinds of new large apartment houses when the ones already in existence are only one-third filled. Anyone who surveys the legitimate theatre closely must he persuaded that present-day audiences are fed up with sex as dramatic fare, and that only when some uncommonly gifted humorist makes it very funny or some genius converts it into tragic irony does there remain to it a measure of its old arbitrary theatrical pull. Even in France, where sex figures almost as largely in the public and private consciousness as the German frontier, the phenomenon is noticeable. The French theatre has gone broke simply because it concerned itself year after year solely and uninterruptedly with a subject that Frenchmen had their fill of outside it and could no longer find distraction and diversion beholding and listening to within its doors.

(Continued on page 98)

(Continued from page 80)

In England and Germany, though perhaps less so in the latter, audiences seem to be tiring equally of the topic. When they want to get a noseful of it, they go to the revues and the girl shows, just as they do in America. For most of the possible changes seem to have been rung on the subject and what is left, save in very rare instances, is simply repetition. There remains, of course, in every country a certain species of theatre customer who is fetched by almost anything that has to do with sex, provided only it be loud enough; but that the intelligent or even semiintelligent customer is beginning to slump back into his seat and grunt is unmistakable.

The fact is, no doubt, that we are getting or have got too sophisticated for sex plays. The revues, with their sketches that have gone the limit and beyond, have made even the boldest of these plays seem tame. And as it takes a very skilful and richly equipped dramatist to restimulate interest in an already sufficiently familiar subject—and as such dramatists are as scarce as mosquitoes in Iceland —an audience with an experience quota above that of a convent girl (under twelve years of age) can no longer work up any interest in them. A comical line may now and again offer a moment's diversion; an ingenious bit of melodrama may invoke a moment's mild attention; or the spectacle of a personable young woman removing her clothes and presenting a view of her charms simultaneously to her Argentinian lover and the American business men out front may momentarily galvanize some of the orchestra chairs; but, in the general run of things, it all ends there and the rest of the evening slides off into doldrums.

SPECULATION EN PASSANT.—For several weeks after the opening of Mr. Earl Carroll's Vanities, the critical gentlemen of the New York press, with a single exception, worked themselves into a combined and fearful lather of indignation over the dirtiness of the show's sketches. Prospective patrons were not only urged to stay away, lest they be contaminated, but were forthrightly commanded to do so. I shall not go into the matter at further length, save freely to admit that the aforementioned sketches were quite as dirty as the critical gentlemen deposed they were, but at the same time to speculate since when the art of criticism has been supposed to concern itself with the morals, rather than with the intelligence, of a community.

EXPLANATION, EXTENUATION AND APOLOGY.—The earlier portions of this critical department go to press several weeks before this final section. In the earlier section you will note that I refer with some favor to the Theatre Guild's production of the play called He. My observations on the play were based on a view of it in its out-of-town performances. Now that I have seen what it is like in its New York presentation, I wish to warn you. If ever a promising production was botched, here you have it. The exhibit on the Guild Theatre stage is no more like that which 1 reviewed in its preliminary revealment than black is like white. The direction is atrociously bad; the acting company plays the light comedy as if it were a requiem; and some idiot has deleted from the manuscript some of the best stuff that was in it when I originally passed on it. If this sort of thing keeps up, I shall urge the Guild to amplify its personnel immediately with such superior theatrical minds as Mr. Michael Kallesser, Mr. Butler Davenport and Mr. Louis B. Mayer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now