Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

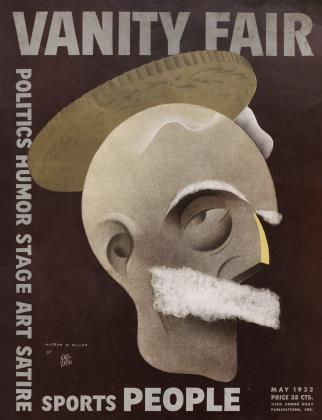

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBolivia Bill

GEORGE MILBURN

A portrait of Governor Bill Murray, of Oklahoma a State in which, it has been often said, "Anything can happen"

Miss Edna Ferber, the lady novelist, wrote by way of preface to her version of doings down old Cimarron way, "Anything can happen in Oklahoma!" Her statement, obviously, is extravagant, hut it is true that some unusual things do happen in Oklahoma. However, any reasonably accurate narrative based on the State's history would not resemble a super-spectacle scenario so much as it would the plot for a hilarious comic opera.

The record is strewn with paradoxes. Example: it is possible, in Oklahoma, for an anachronism to he the man of the hour.

The pioneers have turned out to he poverty-stricken wretches, toiling for men who came in after the country was well populated. Only the Negro slave States have a more unequal distribution of wealth, and no other State in the Union has so great a ratio of tenancy by white farmers. These Oklahoma sharecroppers dwell in the utmost squalor. They are people to whom wooden floors and glass windows represent luxury. They have neither the independence of the Ozark hillbilly nor the individuality of the Texas cowman, their two nearest kin. They never have a dollar that they can call their own. The only thing that they do have is the right to vote, and what dismays the middle-classes in town and city is that they doggedly exercise that right. Every four years, these pioneers-turned-peasants grope toward a savior who promises to ease their burdens. It is their majority that elects the governor of Oklahoma.

"Now the niggers and the poor white trash have a governor!" exclaimed William H. Murray, the people's choice. What he meant was that he had not forgotten whose votes had elected him, as Governors of Oklahoma have had a way of doing. An impartial student of such affairs would probably say that Oklahoma has never had a more sincere or capable executive than the man who is called "Alfalfa Bill," the Sage of Tishomingo, and, less cordially, "Cockleluirr Bill," "Wild Bill," "Bolivia Bill." His predecessors, unfortunately, have been such glorious quacks as to make this a dubious tribute. But lie can still come off very well in comparison with his contemporaries in neighboring States.

It may be that news services, supplied by the bitterly hostile daily press of Oklahoma, have spread abroad the impression that "Alfalfa Bill" Murray is a clown. It is, in fact, a belief prevalent in Oklahoma, and it is not without some foundation. Too often, however, the Governor of Oklahoma's incongruity has been mistaken for buffoonery. He should not be classed, say, with Huey P. Long, the Governor of Louisiana. The Sage of Tishomingo belongs to an era of grand oratory and bust-the-trust and torch-light parades. Almost thirty years have passed since he was first prominent in territorial politics, and neither his ideas nor his physical appearance has changed very much in that time. He is a lonely man today, a vestige of pioneer politics.

There is more evidence for this than his mode of dress and his nickname. One of the most certain and striking ways of dating him is by means of the bawdy jokes he tells— and he tells them very well indeed. He has a rare store of them. Rare, because what impresses his listener immediately is the fact that such stories went out of existence twenty years ago. They have been forgotten. They are lusty, frankly obscene, Rabelaisian in the true sense. The difficulty is, all the situations are those of a horse-and-buggy civilization, and one must be an antiquarian to know when to laugh. It is not enough to say that "Alfalfa Bill" Murray is old-fashioned. He is not of our time.

He makes overt admission to a mild agnosticism, faintly redolent of Ingersoll's lectures and Victorian parlors, although he realizes that his toleration may be injurious in a State thickly populated with Baptists and Methodists. His aged father, a Nazarene preacher, spent years in praying for the conversion of his infidel son, but to no avail. He has made a comparative study of religions, and he says that he considers Confucianism the best of the lot. But he belongs to no church, attends none, and has an outspoken distaste for "manmade creeds." At the same time, he attributes his own rise to a Higher Intelligence that controls the destinies of nations, and he is fond of praying in public to a "Father of All Mercies." He says, "I'm no authority on how to get to Heaven, but I do believe that religion is essential to liberty protected by law."

He is not a prohibitionist but insists that prohibition is an economic, and not a political, issue. He confesses to taking a little whiskey for medicinal purposes, at times, although he is cautious enough not to denounce the Volstead Act. Once, in a jocular mood, he proposed to connect the pipe lines, running from Oklahoma to Chicago, with the stills in the mountainous country of southeastern Oklahoma.

The Governor holds a degree of "Bachelor of Sciences" from the quondam Springtown Male and Female Institute in Texas, but bis bandwriting has never developed beyond the painful scrawl of a schoolboy. A partial explanation for this may be that he spent, all told, only eleven and a half months in school. However limited his formal education, there is no question about his being a native wit and philosopher,—profound only in contrast with the level of intelligence around him.

Usually those biological sports who rise above the mediocrity of the rural community are content to sit whittling on a goodsbox and spitting into the dusty road, delivering all the while original and passably sound criticisms of the government, with occasional flashes of real brilliance. Murray was a curbstone philosopher in the village of Tishomingo, where he set up a law office in 1898. There is that about his gruff speech, his dogmatism, his vindictiveness, that suggests the old-fashioned inferiority complex. Some of his childhood recollections point that way, too. He ran away from home at 13, a scrawny, undernourished, nearsighted child. He had tender hands, and no manual labor could toughen them. He couldn't catch a baseball, and he wasn't good at out-door games. He had encounters with merciless bullies. He was illiterate at that time, and he was made cruelly conscious of his ignorance by boys of his own age who had had a little schooling. But once he could command the reverential wonder of a small town, something set him into action. Perhaps it was the Higher Power lie sometimes credits. More probably it was a series of coincidences.

At least lie made no remarkable success, neither as a lawyer nor as a farmer. Having married a Chickasaw Indian girl in 1899, he was ready, within a short time, to retire to his wife's allotment. There he spent the days lolling in a barrel-stave hammock, reading. He wrote to a professor at Dartmouth, asking for a reading list, and that sympathetic, anonymous man sent him one of those selections of the world's best books. Murray read everything on the list. He would ride over to Tishomingo occasionally and give the town boys an earful of knowledge. So he came to be known as the Sage of Tishomingo.

He seems always to have been a man of quick, violent enthusiasms. About this time he developed such a strong enthusiasm for a newfangled crop called alfalfa that the word got around over the Indian Territory. He was invited to write an article about the plant for a Muskogee newspaper. An inspired editor wrote a headline for it: "Alfalfa Bill on Alfalfa," and coined another, more popular, nickname for the Sage.

The Sage's entrance into politics seems to have been a matter of chance. There was a fairly hare-brained scheme for creating a new State to be called Sequoyah set forth in 1905. Murray, the enthusiast, attended the Sequoyah Convention in Muskogee. There he formed a fateful alliance with a shrewd politician named C. N. Haskell (who afterwards became first Governor of Oklahoma and absconded with the State Capitol, portable at that time because it consisted of nothing but office paraphernalia). Thus, two years later, Murray became president of the Oklahoma constitutional convention.

Continued on page 72

Continued from page 25

He has shown repeatedly that he is a clumsy hand at politics. He was defeated when he ran for governor in the election of 1910. He was elected to Congress in the Democratic year of 1912, and he was in Washington until 1917. However, in making his third campaign for re-election, he snorted at the slogan, "He Kept Us Out of War," something that no astute politician would have done. His jingoistic speeches lost his place in Congress for him. He ran for governor a second time in 1918. and he was again defeated.

It was at this disheartening stage of his career that he developed an enthusiasm for South America. He was pretty well washed up financially. He owed $47,000 and it was necessary for him to sell the Indian allotment to pay his debts. After four years of South American travel, he decided to establish a colony of Oklahoma farmers in Bolivia, a sort of Swiss Family Robinson venture. Hence Bolivia Bill. The project was soon deserted by his bewildered worshipers, hut the Murray family had to live on for five years in the midst of miserable failure.

When he returned from South America in the Fall of 1929, bedraggled and penniless, the whole town of Tishomingo was at the railroad station to meet him. The gruff old prodigal was touched and he muttered, "The loyalty of these people has always puzzled me, hut this last greeting digs me in the ribs."

It was this prod in the ribs, doubtless, that goaded him into the governor's chair the following year. He made his campaign on a shoestring, a very frazzled shoestring. He had everything to win and nothing to lose except a third-time charm. It worked. All the strategy of the politicians could not divert the surge of fanatical worship that came up to him from the impoverished share-croppers.

The Sage is not nearly so impetuous as it would sometimes appear. His play is usually well planned and timed, and he goes forward only with the assurance that he is on safe ground. "You don't catch these hungers making a stern out of me!" he boasts.

'The Summer after his inauguration in January, 1931, he was informed that there were three toll bridges still in operation across Red River on the Texas-Oklahoma border, in spite of the fact that each was paralleled by a free bridge built at the expense of the two States. These free bridges, expensive structures, had been completed for months, with the exception of the approaches on the Texas side. Traffic on the three highways was heavy and the toll bridges were coining money. Murray, having found an early treaty between Spain and the l nited States which granted Oklahoma authority that extended to the southern bank of the river, promptly declared martial law around the three areas. Approaches were hastily erected on the Texas side, the barricades were torn down, and the free bridges were opened. Moreover, Murray ordered the pavement leading to the toll bridges plowed under. All this aroused the indignation of the Texas authorities and the toll bridge owners, hut it delighted motorists. This was the so-called bridge war: nothing very momentous, but it worked. What was more important, it brought "Alfalfa Bill" Murray his first national attention.

Similarly, in his renowned shutdown of Oklahoma oil fields last Summer, frontier theatricals came to the fore. Independent producers already had agreed to the shutdown, and there seems to be no doubt that it would have been effected without the use of force. All that Murray's grandstand play of martial law really did, was lend courage to a vacillating governor and legislature in Texas. The real difficulty was in Texas, and when a curb was placed at last on the great cast-Texas fields that had been flooding the market with cheap oil, the price gradually climbed from ten cents a barrel to seventy cents. The entire credit for the increase in the price of oil went to the belligerent governor of Oklahoma.

He has much more dignity than popular report describes him as having, but he sometimes makes himself ludicrous, unwittingly. He realizes the appeal in owning only one pair of galluses, but there came a day when, changing from one white cotton suit to another, he absent-mindedly walked off to the capitol without any support for his trousers. He spent the day clutching at his dangling breeches with one hand and carrying on the affairs of state with the other. When he is in a sportive mood, he is likely to demonstrate his favorite parlor trick of standing on his head, or to break into a clog dance, no matter whether he is on a platform before a throng or in the executive chamber.

The person who has him pictured as a country bumpkin would be surprised and rather moved to see him come walking into a crowded hall to take his place on the rostrum. He is, at 62, gray and somewhat stooped, but there is dignity in his carriage. The band plays "Hail to the Chief" when he comes down the aisle, and he walks with a stately tread, accepting the tribute of the crowd as his due, without a glance to one side or the other. He has a magnificent stage presence, and he knows how to work all the stops on his deep, drawling voice. His grammar is flawless, although it is rich with colloquialism. He can move an audience to fanatic demonstration, if he is in good form.

He is at a loss as to how to translate his Middleand South-western popularity into Democratic delegations. He is assured of only one. He knows as well as the next man how slim his chances are. and he has never admitted directly that he has presidential aspiration. Less than two years ago, however, he was Oklahoma's most outstanding gubernatorial impossibility.

Already there are thousands of Murray-for-President buttons out, bearing Alfalfa Bill's photograph and the mystic letters "B.B.B.B." Three of these, probably, are the initials for Bread, Bacon and Beans. That second "B", of course, was a mistake in lettering. That should have been a "C". But nowadays, even circuses are out of kilter with the times.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now