Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

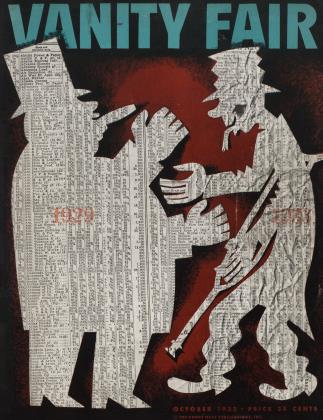

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSophisticate, 1933

RICHARD SHERMAN

A service to those who have hitherto been confused as to the current recipe for mental chic

■ PRESENTING A WONDER-KEY TO URBANITY.—You too can he intelligent, you too can he sophisticated. ... If the components of the baseball and subway mobs are simply one pattern multiplied a millionfold, the same is true on a smaller scale of caviar-eaters and Proust-readers; and therefore it is no longer necessary that any man or woman vegetate on the arid fodder of his own mediocrity. Lift yourself by other people's bootstraps, hitch your wagon to a star, cast out the mote within your eye—in short, enter the society of those whom you have long admired from afar: the intellectually and socially suave. And how? Not by cutting out an attached coupon blank, hut merely by reading the following paragraphs. which form a practical and easily assimilated answer to the question. "What must I do to be regarded as sophisticated today?"

In prefacing this handy guide to contemporary savoir faire, this baedeker to brightness, it must he explained that there will he no attempt at defining either "intelligence" or "sophistication." Like humor and love, they are concepts—or consummations devoutly to he wished—that sour and often disintegrate entirely when subjected to analysis. The only two qualifications are. first, that "intelligence" as here used has no relation to mental profundity; it so happens that much of what the sophisticate says sounds like truth (and maybe is—who knows?), hut the present modest investigation is interested only in exposition; it states hut does not judge. Second, "sophistication" has nothing to do with money.

■ A CODE FOR THE CONSCIOUSLY CLEVER.— General philosophy. Today's sophisticate has no general philosophy, which is one of his claims to sophistication. Nevertheless he does display basic moods, and for want of anything more definite these may he regarded as his working code.

First, you should adopt a mild skepticism toward the universe and all its contents. As will he noted, there are important exceptions to this rule, instances where systematic cynicism is frowned upon and a boyish enthusiasm encouraged, hut they are exceptions only. 1933 skepticism differs from that of past seasons in that it is neither venomous nor hitter: on the contrary, it is of a light-hearted, if complacently fatalistic, nature. The era of savage pessimism has been succeeded by a more tolerant variety of unbelief.

Second (this is an outgrowth of what used to he known as post-war frustration), you should confess a facetious bewilderment in the face of modern life. I) has been impressed upon us in a thousand ways and in as many magazine articles that ours is a swift-moving, complex age; so that now no one is so foolhardy as to pretend to understand what it's all about. This somewhat indefinable—but modish—spirit may best be expressed by a phrase: "I'm sure I can't cope with it. It's much too big (or deep, or fast, or difficult) for me." an attitude applicable to anything from the workings of farm relief to the unscrewing of a pickle jar.

Third, you should fear the obvious as if it were a deadly poison. This precept, apparently so easy of adoption, is fraught with danger due to the fact that although obviousness is to he avoided, simplicity is to he admired. Here lies a pitfall for the novice.

Detachment, ennui, horror of sentimentality, the penchant for satire—these and other time-tested attributes of worldliness are so much taken for granted that they need no further enlargement in an advanced class such as this. Instead, let us proceed from the general to the specific, always remembering that all bright people are much alike on the surface (which is the only thing we are concerned with here) and always being comforted by the knowledge that the surface is seldom scratched.

■ TOPICS OF THE DAY.—Politics. During the fat years, the intelligentsia and the sophisticated—non-synonymous terms which are used interchangeably here as indicating one superior group—didn't have to bother much about politics. They concentrated largely on the arts, on social criticism, and on the titillation of the five senses. Now, however, you must be politically minded, and should he able to discuss municipal, national, and international questions with an air if not of authority at least of lively interest.

Yet at bottom the sophisticate knows that all is still vanity. (Vide General Philosophy.) Such manifestations as the Seabury investigations and the Morgan and Kahn inquiries he views as exciting hut in no way the dawn of a new day. On the other hand, at the present time the enlightened citizen (opposition party enthusiasts excepted, naturally) is likely to approve of the Roosevelt administration, though he remains sufficiently individualistic to quibble about practically all of its policies. It is one of the few instances where his preference coincides with that of John Doe, 85-87 Northern Boulevard, Queens; and because it does coincide he frequently feels compelled to justify it by his own brand of rationalization

As to the particular variety of politics embraced—that, until the mode becomes more thoroughly standardized, is up to each person: a surprising and rather dangerous latitude is allowed. At the moment. Communism appears to be losing caste—the general parlor verdict being that "it's simply another form of autocracy crushing the individual"—and the adherents (Continued on following page) to a benevolent despotism seem to be swelling in number, but neither trend is well enough organized to be termed obligatory. The permanence of the capitalistic regime is still being so hotly debated that it looks as if it would be good conversational material for some time to come.

In general the sophisticate's political views are compounded of Walter Lippmann's writings (since Mr. Lippmann's syndication, the dernier cri is to scorn him: watch this—it may become the vogue) ; of cursory reading from the liberal weeklies; of the direct opposite of whatever stand is taken by the Hearst papers or the Chicago Tribune: and of how the political leaders look and talk in the news

It is perhaps superfluous to point out that no one can hope to be a true sophisticate and still claim membership in and uphold the ideals of the Republican Party. Among the intellectually élite, the G.O.P. has long since been relegated to the role of national comic, and only the most iconoclastic dare to mention Hoover without automatically accompanying the name with a smile.

Economic beliefs. Whether single-taxer or Marxist or old-fashioned gold standard bearer, you should be ready to declare that after all money isn't everything. To be rich is also to be slightly vulgar. Those who do happen to he cursed with great wealth must pursue an ascetic course if they arc to escape the accusation of Philistinism.

Whatever your financial status, you should aver that what you really want is to live on the land and off its fruits. Obviously nothing would lure the sophisticate from the city, but that is beside the point: he gives the impression that his chief desire is to get away from this mad treadmill of machine age work and pleasure. This pose, so effective today, was equally popular in France during the eighteenth century.

If you have made a success in your own profession or business, you should modestly laugh it off. Success, you say, depends on the breaks—and the breaks were with you, that's all. Work, persistence, honest effort are but snares and delusions.

To regret the passing of the boom years is bad form. The attitude to express now is that the crash was beneficial because it brought us to our senses. Although there was actually considerable unemployment and penny-pinching then too, the years 1924-1929 have become in retrospect one long Cecil B. De Mille-ian orgy. "What fools we were then" is today's refrain, and when Wall Street goes bullish now it is well to he heard remarking (between calls to your broker), "Maybe it's prosperity and maybe not—hut heaven keep us from another boom." Everybody else wants a boom; you alone appreciate its perils.

You will be considered knowing if you maintain that big business is essentially bad business because of its impersonality and lack of individualism. But big business under state direction that is, collectivism (a bigger business than we yet know)—is big business with the curse removed.

■ SEMI-SERIOUS CONVERSATION.—Social beliefs. Pronounced pacifism is no longer in favor. You should freely admit the horror and futility of war—but, you argue realistically, "After all, one can't contravert human nature, you know." Disarmament activities are therefore to he viewed with a jaundiced eye.

You should distrust the wonders of science and modernity. Just as the farm is theoretically to be preferred to the city, so the buggy is to he preferred to the automobile, theoretically. The world, you maintain, was a happier place before the Industrial Revolution, and the Century of Progress is a hollow monument

"New-school" methods of teaching should he condemned as unsatisfactory. There is a definite trend back to the conservative spare-the-rod-and-spoil-the-child theory.

Missionary work, either religious or pedagogical, is crass interference with the lives of .others. So, in fact, is all social service. Those who participate in it do so because their egos are inflated by the gratitude of the saved. The Congo savage is a happy man when left to himself; to try to better his state will only harm him.

Now that the feminists have fought and won their battle, feminism is not à la mode. The bright woman should do everything within her power to conceal her brightness. "Careers" for women have become old-fashioned; she now wants it clearly understood that her place is in the home.

Even though you know nothing about it, you will do well to maintain that the Orient is due for a renaissance in power. (Their culture, you are convinced, has always been superior to that of the West.) Nordic supremacy is to be hooted at. England, you believe, is on the brink of a decline and fall equal to that of the Roman Empire in utter finality.

You should hold that democracy is a vulgar form of government, and that almost anything is preferable to it-anything from Communism to an absolute monarchy.

Ethics and morals. Religion itself need not consume much of your attention. They say that in England there has been a drift toward formal piety, but it has not caught on over here except among Buchmanites. God is still out. To be a practicing Methodist, Baptist, or Congregationalist, for instance, is to eliminate oneself immediately from entry into the haut monde. Episcopalianism and Catholicism are a little more possible, but even they are dangerous unless rationalized in some unique manner. Never forget that as a sophisticate you may participate in certain mass movements but that your reasons for so doing must not be mass reasons.

As for sex—if there is a trend at all, it is toward conservatism. Easy and frequent divorce is out of fashion. Since the depression, discontented wives and husbands have gallantly cultivated the mustn't-grumble spirit: they grin and bear it. Naturally this code results in many hardships, but there is a compensatory feeling of martyrdom to be enjoyed.

There is a vogue for larger families. The sophisticated young wife of today talks at length about the number of children she wants to have—"when we can afford them."

Perversion is a little old-fashioned at the moment. You can no longer hope to gain the appearance of worldliness merely by mentioning the words "homosexual" and "Lesbian." Some forecasters prophesy that necrophilism, or something equally bizarre, will be the next fad to capture the fancy of select circles. Although this may be true, it is best for the present to stick to well-trodden paths. Never he the first to try the new, or the last to put the old aside.

Drunkenness is on the wane. Since the arrival of beer, it is considered gauche either to serve or to imbibe a steady succession of postprandial highballs. The younger generation is especially emphatic in its scorn of drinking. They do, however, spend long hours in elaborate discussions of wines.

Personal physical health has made an astounding comeback. Whereas the sophisticate used to scorn bodily vigor and perfection, he now goes in for all the sun, sea. and air he can get. Despite this movement, it is still good to ridicule early rising and before-breakfast exercise as both barbaric and vulgar.

(Continued on page 53)

(Continued from page 28)

THE FINER SIDE OF LIFE.—The arts. Since this classification occupies such a large portion of the conversational patter to be used, special emphasis must be placed upon it.

First, consider literature. The classics are now so well pigeon-holed (Dante, awesome; Dickens, quaint; Shelley, lyric; Voltaire, cynical; etc.) that it is not necessary actually to have read them. As for the writers after 1900—Conrad, Hardy, Galsworthy, and Bennett are dead; not only in the sense that they have ceased to breathe hut because their books are passe. Among the current Americans, Hemingway, Faulkner, and Dos Bassos are holding up well. The old guard— Cabell, Dreiser, Mencken, Nathan (in fact the whole staff of the American Spectator)—is now regarded as somewhat pathetic.

In the dramatic field. Barrie and Shaw are of course merely relics. (Shaw, too, is a "pathetic figure.") Middle-European playwrights are quoted very low, Molnár included. O'Neill has ceased to be the delight of the intellectuals: he is becoming fanny—funny and more than a little boring. The adulation of women's clubs has been his downfall as far as his sophisticated public is concerned. The same fate seems to be hovering over Noel Coward, whose Design for Living brought forth mutterings of discontent from the audience for whom it presumably was written. Likewise with the Theatre Guild which, by widening its subscription list, has lost its hold on the best people. Dowagers may still attend its first nights as a privilege of age.

And now for music, which may immediately be dismissed with one name. It is permissible for you to say that God, Shakespeare, and your mother bore you, but to admit a coolness toward Bach is to he guilty of a deplorable lack of taste. Aside from him, the safest musical bets are those least known -preferably people whose works have never been played in this country. Ravel is a trickster, De Hussy a soporific, Tchaikowsky a tunesmith. Wagner a chore. Opera, of course, is artistically on a par with the horse show.

Lastly, art. Due to the fact that the galleries have been bard hit during the depression, there have been fewer shows than usual and consequently fewer chances for new enthusiasms. Recently there has been a vogue for early American art: American primitives are in high favor, and Copley and Stuart elicit eyebrow-raising and patronizing smiles. Mexican folk art seemed to have reached its peak boom last year, but as long as Rivera figures in the headlines it will probably still be good. In architecture, the vertical (skyscrapers) has been displaced by the horizontal (workmen's homes) as the current favorite.

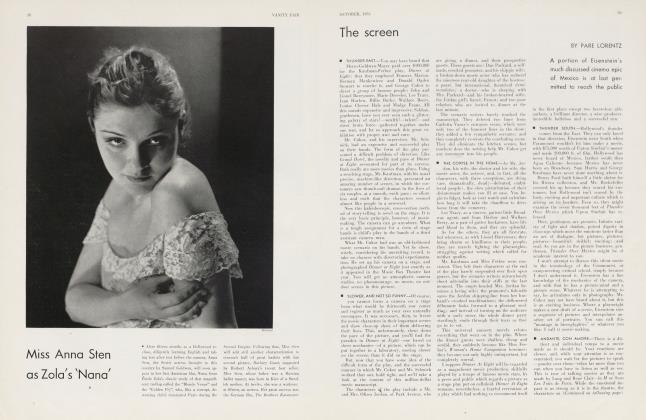

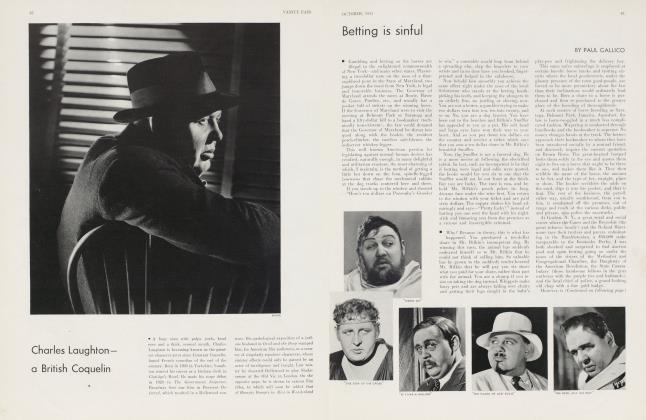

ODDS AND ENDS.—Aside from the above categories—which cover in a regrettably sketchy fashion the main channels of sophisticated conversation and thought—there is also a conglomerate list of subjects on which it is well to be prepared. Take, for instance, the movies. Disdaining the films as lowbrow is distinctly a blunder. You should be able to talk knowingly about them—usually in a satirical manner—and you should he familiar with the work and in some instances the private lives of the various players. Certain of these (Janet Gaynor, Wheeler and Woolsey, Joe F. Brown. Ruth Chatterton, Constance Bennett, Marion Davies) are to be scorned; others (Garbo, Dietrich. Mickey Mouse, Mae West. Charles Laughton. Katharine Hepburn) are to be admired and championed.

By no means to be overlooked is the let's-be-crazy movement. This may he defined as the tendency among intelligent people to become rhapsodical about certain unintelligent or lowbrow things; it is responsible for the fervor which is expended on the Minsky Brothers' burlesque, the comic strips (though they lack the smartness they had when Gilbert Seldes was discovering them), Walter Winchell, Variety. parlor games, roller skating, attending dance marathons, and similar divertissements. It is all very simple, all very innocent, and it is done with a childlike gayety and naïveté.

To forecast what live fads will be this winter is impossible, since they are based on un-reason rather than reason. One may, of course, form one's own cult. Thus you might assume a perverted interest in the rising-hour pep talks of the radio gentleman known as "Cheerio." The procedure here would be to announce publicly that you get up early just in order to hear his wisdom. "You don't like him?" you ask, with mock incredulousness; "Oh. 1 think he's marvelous."

Mention of the word "marvelous" brings to mind still another matter—trivial, it is true, but important in its way. That is the terminology and oral embroidery to be used in talking. The jargon of psychology—"defense mechanism," "inferiority complex," etc.—is not used with its former frequency. At first embraced eagerly by the sophisticated, it has spread so widely among the common people that it has ceased to carry its cachet of novelty. Gutter slang is always welcome: "nuts," "lousy," "scram," and their kin. Slang as a whole, however, should be used with discrimination because it so easily dales the user. There are also certain standard forms—"a sound person," "terribly amusing," "so gay," "a swell guy," "so what?"—which go well: and to sprinkle "as a matter of fact" throughout your conversation lends a desirable impression of glibness. For women the restricted use of profanity is advisable; a "god-damned" here and a "Christ!" there will do much toward brightening an otherwise dull conversation. However, a constant stream of oaths is not comme il faut except for famous actresses. It is also good to stud your chatter with selected bromides: examples, "New York is a wonderful place to visit, but I wouldn't live there," "I don't know anything about art. but I do know what I like." A burlesque archness and a special inflection of voice are employed on these occasions.

(Continued on page 63)

(Continued from page 53)

As for manners, it is to be noted that the importance of table etiquette as a criterion of true worth has dwindled enormously. It is. in fact, a rather shrewd move to cultivate a peasant-like simplicity in your approach to food and drink; a frank and artless directness in soup-eating and chicken-gnawing is to be approved.

And mores? Arrogant rudeness is on the decline. There is prevalent a general spirit of live-and-let-live, and bores are tolerated with a Christian forbearance. Gentlemen and ladies, the current mode says, never take advantage of the fact that they are gentlemen and ladies. Oscar Wilde's definition of a gentleman as "one who is never unintentionally rude" is as obsolete as Oscar Wilde's collected works.Indeed, anyone who makes a distinction between a man and a gentleman is no gentleman.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now