Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

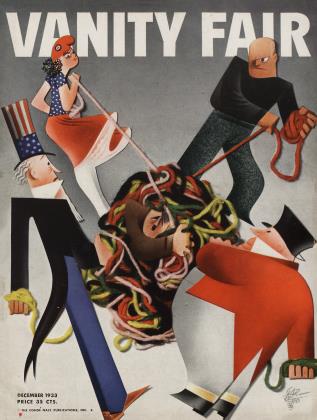

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe pulse of revolution

ROSIE GRÄFENBERG

A retracing of the revolution-fever in other nations at other times, and the lessons they may hold for us

They call it a "New Deal"; hut could they not just as well call it a revolution, although a peaceable one? There can be only a few people left who still regard the events of March 4th and following as nothing else than the natural results of a change in Administration. As the events of these first nine Roosevelt months move into history, we begin to piece them together and assemble their significance. And the sum total has many of the characteristics of a coup d'é.etat.

" Was it a revolution or was it not a revolution? The best way of finding out is to try to determine what ordinarily constitutes a revolution, and what signs attend its progress. It is not difficult to find contemporary examples; there has a^eady been another revolution in 1933, and as to its reality there can be no doubt. Historic parallels, such as those I am about to offer, may be of questionable value when applied

to the current American situation—the overthrow of one party and the complete dominance of another—but there can be no denying that the word "revolution" has lurked in the minds of many during the past three years, and almost any light that one may throw on revolutions in other countries should he welcome in this one. First, consider the most recent exhibit—Germany.

In the first days of the Nazi coup d'etat in Berlin last spring a smart young stormtrooper stood in uniform and swastika arm-band at a crowded corner of the Kurfiirstendamm and called out, "'Out with the Jews!' A highly interesting brochure about the criminals of the Republic. 'Out with the Jews!' Only twenty Pfennigs." He held up a pile of copies. Right next to him stood a little old woman calling out, "Fresh lilies of the valley. Only ten Pfennigs"— and held up little hunches to the passersby. Most of the passers-by decided upon tin? lilies of the valley, at the expense of the highly interesting brochure. Perhaps because they cost less. Perhaps because the flowers stood for something in their lives which had more meaning for them than the highly interesting brochure.

Another way of saying it would be that in every revolution there remains a large degree of ordinary life, of mere day-to-dayness, which cannot easily he overrun by politics. For those who have to go through them, revolutions have not even a clear beginning. The overthrow is not identified with any one definite event, which changes existence with a single blow. On the day of the fall of the Bastille, that July 14th which history has decided upon as the birthday of the French Revolution, Louis XVI wrote down in his journal that he was out hunting.

Like any modern technical machine, revolution runs along almost silently and elegantly, as if on rubber tires. Street-fights and barricades are no longer its natural symptoms; they are its traffic interruptions. In Petrograd, on the day the Bolsheviks seized power, theatres, movies and restaurants were open, and only those who listened closely could detect that a coup d'etat was just being carried out.

But the Fascist revolutions—such as took place in 1923 in Italy and in 1933 in Germany—proceed with even greater elegance. They remain largely within the frame of legality; they are constitutional revolutions. Since history has accustomed us to associate revolutions with violence and bloodshed, frequent doubts arise as to whether these latter ones are to be considered as revolutions at all. Actually, however, the only change is one of revolutionary tactics: now the violence and bloodshed are carried out in the years before the actual coup d'etat.

Thus the four years which preceded

the so-called March on Rome were filled with the violent deeds of an actual civil war. The actual March on Rome, however, was commanded by Mussolini from his sober and comfortable Pullman car: he received power from the hands of the king just as if he had been any prime minister. It was only later that the March on Rome was elevated into a revolutionary symbol.

It was also in the years which preceded Hitler's victory that the stabbings and shootings mounted up between the Nazis on the one hand, and the Communists, Socialists and Reichsbanner-men on the other. If Hitler now totals the number of casualties of the Nazi revolution at 40,000 (apparently in order to prove to the world that a full-blooded revolution really took place), the figure is probably exaggerated. Nevertheless, a more or less latent civil war had been going on. But when Adolf Hitler actually took control, he did so through parliamentary elections—strictly according to the rules of the Weimar Constitution. The German people surrendered their liberties voluntarily, not under the pressure of physical violence. Although at the time there was much talk of a national revolution, the only symbol of it was a torchlight parade through the Wilhelmstrasse.

The motor of Everyday keeps on running even while the social structure creaks in each of its joints. It runs with the fuel

of habit, of technical organization, and of the mental lethargy of the individual. That this motor is going to run dry, that it has no inherent force, and that in a short time it is going to stand still forever, one may fail to recognize. This everyday quality deceives one about the fact of revolution; it acts as a sort of self-expression for the condemned classes.

Thus on the day that Lenin seized control, Grand Duchess Marie traveled by train from Moscow to Petrograd; in her memoirs she tells how unbelievable and how comforting it was still to find clean sleeping cars and polite conductors on board. Here technique and organization had withstood the rush of revolution. Thus on the morning after Hitler became Dictator of Germany, the charming Berlin modiste Mine. Berthe, called up her elegant clientèle to tell them that Paris was now wearing Alice-in-Wonderland headdresses and that the new hats were being worn very high on the head. She took absolutely no cognizance of the fact that the revolution was affecting, rather intimately, the lives of all the accustomed wearers of her Paris hats. And, as it turned out, that was very wise of her. Mine. Berthe did an excellent business with her new hats in those April weeks. Her charmingly perfumed shop became an oasis of elegance and unconcern (Continued on page 65)

(Continued from page 51)

for her clientele—in a word, a symbol of the past. As these ladies had themselves made beautiful, they carried out the regular gestures of the ruling class, and forgot for the moment that these gestures had become senseless in the face of the new revolution.

While the tide of revolution rises higher and higher, the condemned classes hold on to this everydayness as to a raft. Even after the Fall of the Bastille, the French aristocracy staged parties that, even if they were a hit thinned out by the guillotine, were nevertheless still charming. While Hitler was already at work to drive them out, the Jewish and left-wing intellectuals gathered, according to old habit in the Eden Bar in Berlin. So, also, the Russian aristocrats continued, for a longer time than was healthy for them, to listen to the melancholy songs of the gypsies in Petrograd nightclubs.

One can recognize the condemned classes by their failure to sense danger. One can recognize them by that even when a revolution is remote.

The philosophy of a Voltaire and a Diderot, which thought the French Revolution out in advance, was proclaimed by the French aristocrats. Marie Antoinette and all the princes and princesses made pilgrimages to the grave of Rousseau, whose hack-tonature thinking placed a reductio ad absurdum upon the whole monarchical system. At the premiere of the Mariage de Figaro in 1784, the court fought for tickets, and the play, with its challenge against aristocracy, was greeted with endless applause. "I did not think it would he so amusing to see one's self burned in effigy," the dancer Guimard said at the time.

Inner uncertainty, feelings of guilt come over the ruling class; and with them, a surrender of its usual forms and formalities. When Marie Antoinette, bored by the high ceremony of Versailles, fled to the Rousseau-like country atmosphere of the Trianon, she resigned the decorative symbols of power. But it is never a good thing for rulers to try to live as other people do. That fact was borne out at Tsarskoje Selo, where, close by the grandiose baroque palace of Catherine the Great, the last Czar and his family inhabited a modest villa, such as is preferred by the middle-class, with intensive family life and few social duties. Among the thin art-nouveau furnishings in the boudoir of the Czarina, there was still much talk of "rule by the grace of God," but the belief in that had to be kept alive by peculiar medicine-men such as Rasputin.

The hour in which the ruling class capitulates before the ideology of revolution is the greatest hour of the revolutionary idea; it may also be the smallest hour of the revolutionary party. It is a defeat for the revolutionary party because its fire seems to have been stolen by the still ruling class; it is a victory for the revolutionary idea, which now is in the act of putting itself peaceably in power. It may be questioned what need there is for an actual overthrow, once this victory has been attained.

But a revolution, it must be remembered, is a matter not of ideas, but of men for whom the ideas are vehicles to he used in the attainment of power. These men are not satisfied if the old world of ideas is discredited and the new one has conquered. They are not interested in having their brand-new theories realized by the previously riding class; they want to become the ruling class themselves. For that reason the old ruling class, despite its most excellent understanding of the new ideas, must be overthrown.

For this purpose, it is not enough to prove that the former system was bad; proof must be given that the formerly ruling class was bad.

The actual overthrow thus finds the old ruling class in no sense at the high point of its strength, hut in a time of considerable poverty in ideas and materials. The French and Russian aristocracy—filled with inhibitions of guilt, and disintegrating under the new teachings—really knew neither what it should defend nor how it should defend it. Neither the Left nor the Jewish bourgeoisie offered any strong opposition as the Nazis rose up. No leading voice in Germany spoke out for democracy—as if its leading representatives had forgotten what might be said in favor of it. It is the material and ideological poverty of the previously ruling class that explains its thoughtlessness, its stoic resignation, and its undiscerning entry into mistaken alliances on the outbreak of revolution. If one looks closely, one realizes that revolution creates nothing new, hut rather puts its seal upon that which is already there. The signal for revolution has always been given by the ruling classes themselves.

Falling in revolutions is like falling in love. It is a falling without an exact beginning and with an uncertain end. One never knows whether one has finally landed at the bottom or not. The French tell a story of a workman who tumbles off a roof and calls out. as he passes the first floor, "If only it lasts this way!" But his fate is decided when he strikes the ground.

Sometimes it happens that one doesn't strike the ground so hard. Some of the ci-devants save themselves because they are especially cowardly; others save themselves because they are especially courageous. One has the largest chance if one holds to the firm intention to survive at all costs. In the language of modern revolution, that would be called placing one's feet firmly upon the ground of facts. One should he warned against becoming a martyr of the Heretofore. That way, one only wins displeasure in the eyes of the neighbors, and one helps the cause almost not at all. There is no practical guide for revolutions; the only certain means to avoid trouble is —not to let yourself fall into revolution.

The question is still open: does the current performance of American government have the characteristics of a revolution? I would not attempt to answer it. I only submit the symptoms which have marked the appearance and the progress of great European revolutions. If you detect those symptoms here-well, you may get ahead of your fellows.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now