Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCapitalism on trial

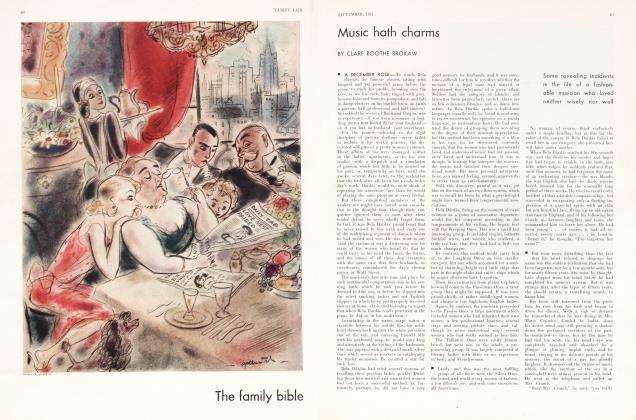

CLARE BOOTHE BROKAW

WASHINGTON ROAD-SHOW.—In Washington, with the final enactment into law of a complete national relief program, the curtain has been rung up on the first act of a great human comedy called "Capitalism on Trial". Authored by an aspiring and heretofore unknown group of politicoeconomists hopefully dubbed the Brain Trust, produced by that gallant and daring entrepreneur, our current President, stagemanaged by Congress—this 10-20-30 billion dollar thriller promises the public—poor compelled audience—a conventional Happy Ending of the depression. Surely this Gargantuan drama offers an all-star cast. Czars of industry, steel barons, labor lords, financial kings, and a starry-eyed retinue of economists will strut and descant for all your money's worth along the green banks of the Potomac. A vast supporting cast of lesser industrial lights has been recruited from "the sticks"; every Main Street from Seattle to Tampa has proudly sent an incipient Barrymore of Industry to tread the Washington boards, to crowd the wings and supply convincing off-stage noises. . . .

THE DEVIL WAS SICK.—Oddly enough, not even the most gouty and Calvinistic critic complains that this massive production is a purely artistic experiment, or that it springs, like Pallas Athene, from the head of a Jovian Moley. Success or no, it is, in essence, the answer to a wide popular demand. During (he past sad four years, weaknesses in the mechanism of the capitalistic system have become as painfully apparent as a wen on the leading man's nose; it is now proposed publicly to remove the disfigurement leaving, if possible, the charming, if somewhat aristocratic appendage intact. No, such an analogy is superficial. It goes deeper than that; deeper than a mere aesthetic operation on the handsome face of Capitalism. Lately, it has been impossible to ignore the searching, bitter questions that have been raised concerning the vital organism, the deep anatomy of our system of economy. This is the question: Is that system sick unto death? Dying? Had it not better die? Even in the Ivory (headed) Towers of the Last Bugged Individualists the sharp doubt has penetrated, spreading confusion and dismay. Nice pal liatives and plausible cures; obvious quackeries without number, have been suggested; Capitalism is a native American, and dies hard; some sav it is so tough that it will live despite disease or remedy; at any rate, we have resolved to try, somehow, to ameliorate its sufferings.

This fine charity, which yon may hope is not misguided, has crystallized itself into legislative prescriptions, filled during the mad months of March, and while April laughed her girlish laughter, by both your Houses. Most drastic of these prescriptions, strong and curiously pink, is the medicine known as "The National Recovery Act". Watching our desperate Capitalism reach for it. cynical Communism quotes:

"The Devil was sick.

The Devil a monk would be;

The Devil got well;

The devil a monk was he!"

A MIGHTY ACT OF MAN.

But let us forget, thank you. all strained metaphor, and turn to journalese. The great, informed press has spoken of The Industrial Recovery Act in superlatives somewhat reminiscent of Barnum and Bailey's "100 panoplied and Hollywood's mastodonic films"; say the editors: The act is a "colossal experiment", "a prodigious trust", "an infinite undertaking, complicated beyond mortal conception", "a gigantic, stupendous. Brobdingnagian enterprise", "the most revolutionary, unparalleled legislation in the history of the country". Left-Wing commentators claim that it "promises economic emancipation" etc., etc., and, since you are always offered a reasonable choice in these United States. Right-Wingers find in it "economic chaos", "disgraceful political compromise", "blighting bureaucracy". . . . Here and there we hear opinions tempered to the winds of public opinion. Robert Lund, the President of the National Manufacturers Association, and Henry I. Harriman, our own U. S. Chamber of Commerce's enlightened head, gave it calm hut patriotic approval. The latter gentleman found it not entirely to his heart's desire, but, a stalwart, stood by, calling on Business for "wholehearted cooperation" with the provisions of The Industrial Act.

■ DESCRIPTION OF A BEHEMOTH.—Let's examine this Wonder-Bill. The Act contains two major divisions: one creating a public works program of $3,300,000,000 to he spent as quickly as possible; the second suspending the Sherman Anti-Trust Laws and allowing, even forcing, industry to establish codes of practice that may include the regulation of wages, hours, and production, with promised watchfulness by the government to prevent exploitation of the consumer through unfair prices. Elsewhere this process has been outlined as, first: exhortation (to the patriotic impulse, no doubt); second, persuasion; third, negotiation; and in the event of failure to coax reason into the thick skull of a recalcitrant industrialist, the thumping use of the license club, a Governmental bludgeon guaranteed to produce "wholehearted" cooperation.

The purposes of the Bill are surely well-meant and clear. Wholesale regulation of industry in order (a) to improve the prevalent unsocial level of wages, and, (b) to reduce hours so that available employment shall be more widely distributed. Its intention is also the application of a synthetic stimulus to industry. to raise prices, reduce the burden on debtors, increase employment; all this to the end that the purchasing power of the masses may be raised—and the capitalist restored to his proper heaven, why not?

Why not, indeed? Well, to the capitalist, to capitalism, this bill, whose obvious purposes are all "good news", is, nevertheless, fraught with disturbing implications, unorthodox potentialities, which should, if they don't, challenge his wary interest.

For, it is by no means certain that the objectives of the National Rescue Act can be attained without the adoption, in future, of regulations even broader, even more stringent, than those inherent in the determination of minimum wages and maximum hours. In fact, industry itself clamors for price-fixing, which means to business chances of profits, and limitation of production, in order to avoid the adverse effects of liquidation of capital unwisely invested in over-exploited fields.

The power to determine all of these factors is inherent in the Bill. Wages, hours, prices, profits, and production can be set for interstate commerce by the Administrator.

So it would seem that the editors are right: here is the broadest instrument of "planned economy" ever wielded by a so-called capitalistic country; an instrument forged in a philosophy utterly remote from the principle of laissez-faire and rugged individualism so dear to the "new economics" of the '29-ers.

Continued on page 51

Continued from page 19

The administration of the Bill, the technique of its use, is at this writing still in a formative stage. It will he Herculean labor. One looks with sympathetic misgivings at that brash soldier, General Hugh Johnson, who has assumed the task of cleaning so many Augean stables. What one brain can fully comprehend the size and complexity of an undertaking to regulate American business? Who could visualize with sweet justice, undertake with wise strength, the regulation of more than 7.000 separate industries, comprising 500.000 or more business institutions which draw upon a laboring force of over 45.000.000 men and women who are employed in the production and distribution of 60 to 80 billions of dollars of divers goods and dissimilar services, working tinder varied living conditions and climates? No, your head would split with this effort. As a matter of fact, the whole thing is likely to tell quite a lot on the General's constitution.

In order to escape the necessity of administrative omniscience, the effort is being made to urge each industry to establish its own code of practices, or to submit basic codes upon which the Administrator and his board may improvise or build. This "self-determination" of industries (to raise a not too reassuring Wilsonian echo) will receive the sanction of Government under the licensing clause. The policing of codes after establishment, the jurisdiction over practices, the correction of abuses, and even the imposition of wiser, or more social codes upon those who initiate poor ones, are complexities awaiting the solution of the proper and future time.

Code interpretation, administrative technique:—these are matters of time. A more immediate solution may be required of the potentially if not actually impending struggle between Labor and Employer, arising out of the Collective Bargaining Clause, which Labor, with grand astuteness, has been quick to emphasize and interpret as a governmental implication that unionization is the sine qua non of a fair deal to labor. The employer has swallowed a hitter enough pill, with higher wages and shorter hours; will he swallow the closed-shop pill as well, or must we face strikes, lockouts, a real labor warfare? Undoubtedly the Act. promising as it does some good to all. if forcefully and above all diplomatically administrated. will weather this storm on the horizon.

lint does not all this administrative technique indicate a huge bureaucracy? It does. For better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, business has gone to bed with government, and the two are one. Now, in Washington, is burgeoning a bureaucracy of such staggering proportions as to make that extinct dinosaur, the Farm Board, blush with shame of insignificance. (Eyewitnesses tell how the ante-rooms of the Industrial Control Board creep with insistent job-hunters, ravenous Democrats, slick log-rollers; even in the Sanctum Sanctorum of the honorable General who, bless him, stays close to the open window, there is already the familiar, unmistakable odor of political decomposition. It is, in fact, such sights as these which will provide foresighted editors with material to be placed aside in bulky folders marked "Super-stupendous Senate Investigation of 1936".)

THE CAPITALIST'S DETOUR. And the future? Even the most incurable political wise-acres, and the Wall Street diviners admit that the future, as conditioned by this bill, is hidden in a nasty, soupy fog. Nevertheless, it's now the fashion to claim that it is possible dimly to see stretching away before us two distinct roads—Left and Right along which the National Recovery Act may carry us. At this point the capitalist pricks up his ears, wipes the sentimental mist of the Bulhnarket days from his eyeglasses, and peers with myopic intenlness into his country's future. . . .

Now, your capitalist is a wishfulthinking fellow. Therefore, he asserts that the Recovery Act is with us only to provide a brief detour while the broad highwaymen of his class are out repairing the main route. That detour, which he thinks he sees in the fog ahead, must eventually lead us back to the capitalist road, 1926 style, with all cracks filled in. To prove his point, he argues: This is a temporary emergency measure! Emergency, yes; temporary?difficult to believe. Emergency acts, like five o'clock pick-meups, have a bad habit of becoming regular institutions.

But all riglit. let's agree, for a brief moment, with our dreamy-eyed, hardboiled business man who can see no danger to Capitalism in the Act. that the hill itself is only temporarily placed upon our statute books. Then. I here is not only no danger, but even a rosy side to the thing. Many capitalists are employers, who see under Government regulation the protection, or rather the rebirth of profits, which have been stamped out by "rugged individualism" rampant. Their chief interest, by no means altruistic, in the Act. lies, not in minimum wages and maximum hours, hut in minimum prices and limited competition, through the regulation of selling practices, and even production. Wage and hour schedules they can take, if they're going to get more profits, and escape inventory headaches! Now. why do you suppose these optimists fail to see that the expansion of the National "Rescue" Act into a detailed code of trade operations, means also increased Government control, and. therefore, minimization of the temporary effect and character of the Bill?

But, to go on with the capitalists' argument: the Bill's continued administration is going to cost the country such a whale of a lot of money, the country won't stand for it long. When (they say) the big, publicspirited boys who are down there now volunteering their aid to the courageous General in his war on Depression, grow weary, or are called home to see that the cashier is not raiding the till, or factory hands sabotaging the machinery, or—when the profits hack there cease altogether, or begin to roll in again—the big boys will start the exodus of giant brains from Washington. That is when to administer the bill will cost the little ole taxpayer a pretty penny, for at that point will be installed a paid-for, completely political bureaucracy. Besides, the mere administration of such a legislative Leviathan will become too onerous, too unwieldy for survival. (Note, in passing: It is intimated, in Washington, that the canny Mr. Johnson is even now working upon a plan that will impose a small fee upon each industry regulated under this act, the collective fees to pay the running administrative expenses.)

Continued on page 55

Continued from page 51

However, neither the time restriction clause in the bill, nor the cost and difficulty of administration is your wishful-thinking capitalist's argumentative ace-in-the-hole.

For there is one thing upon which every capitalist apologist for the bill does unite in loud-mouthed harmony with his brothers. Their chorus of faith in the Detour-back-to-old-fashioned-Capitalism is unanimously based on a touching belief in the present capitalistic colouring of the Administrative personnel.

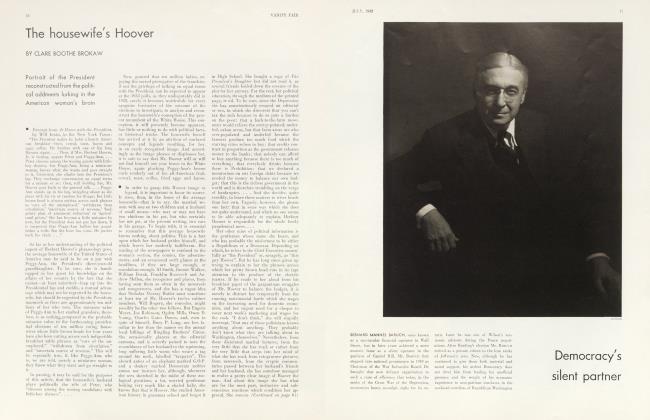

Oh, the time never was when one good capitalist could not look another square in the eye!—and kick his competitor squarely in the breeches. . . . The dynamic General Johnson, the gentle Mr. Gerard Swope, the placid Louis Kirstein, the forthright, upstanding, outspoken, hard-hitting, clean-shaven Messrs. Vereen, Teagle. Gates, Whiteside and Sloan have this in common: they have all been American Money-Makers in their time. Moreover, they are in the habit of slaying after school to talk it over with Herr Professor Bernard Mannes Baruch, who has taught a realistic thing or two to Brain Trustees, Farm Folk, Wall Street Magnates, Foreign Pirates of one sort or another, and five (count them—five) presidents. It is inconceivable to anybody, even Mr. Moley, that such men should betray, not each other, but their deep-rooted instincts. Vision they may have, publicspirited they may be—but their brains are cast in an ancient mold. The mold is familiar, the thought-pattern pleasant to the Main Street shop-owner, as well as to the Wall Street baron; the dyed-in-the-wool capitalist rests his case on this knowledge: The National Recovery Act cannot take the left-hand road, for we are being driven by right-handed drivers.

They point out, too, that the temper of the American people applauds this belief. We Americans enjoy established order; we have no stomach for prolonged Government ownership or control; the history of the depression proves we can suffer anything except a loss of profits in preference to active Socialism.

Perhaps, perhaps. . . . Their guess is as good as Mr. Norman Thomas'; better, as witness the election returns. But who would be so rash as to claim he could gauge what would be, two years hence, the temper of a country in which farmers' strikes, tax evasions, general lack of respect for law, a complete submergence of a Republican electorate, continued as the trend of the hour?

In this fashion the capitalists have taken to their bosoms this Bill and this is the way they have argued: limitation by law, expense and unwieldiness of administration, homogeneity of personnel and the nonsocialistic temper of the people; for the argument much has been, and much can be, said.

ROUTE NO. 2.—But there is, and you have heard it on every side, a second road, leading into the future—a road which goes straight to State Socialism. It, too, has its advocates who point the signs quite as persuasively as the capitalist. The hill, they say, will survive the limitation of law, the constriction of personnel, the burden of Administration and will find, in so doing, friendly temper among the masses. It is their belief that this Recovery Act is the first step in the inevitable march of our economy from its present state to such a modified status of capitalism as to he quite definitely Socialism. There are Voices, and some of them have found the President's good ear, who say frankly that the bill is consciously aimed at the necessary redistribution of wealth (Vide: the Social philosophy of Candidate Roosevelt, as expressed in his campaign speech before the Commonwealth Club of San Francisco) and towards a planned economy with clearly limited rights for private ownership. According to this capitalist-opposition camp, industry has but one obligation: to render service, not a divine right to make profit; and this service must be assured to the people by the people, through the adequate control of their own Federal Government.

To these advocates of an American State Socialism, the control of wages is only the beginning. They would convert the temporary Act into a more positive and permanent form of social control. Not only do they applaud minimum prices, hut they will cheer to the echo the fixation of maximum prices above which shoes and ships and sealing wax can not be sold. Controlled production gauged to demand follows inevitably—because without this, the ogre of over-production can not be slain. But the second-roaders do not stop there; they could not, if they would. For, with prices and production and distribution and profits fixed like constellations in immutable ever-smiling economic heavens, the direction of profits must also be controlled, and the flow of capital directed by state agencies. With a rigid regulation of profit will new capital be risked in new enterprises? Presumably not: the Government, a whale among the minnows, will swallow these profits through the sale of its own bonds, and then venture this borrowed capital at its own risk. Then indeed the Government will' be, not in Business, but Business itself: private initiative will languish and die, and the stream of production and distribution will course entirely through Federal Halls. ROUTE NO. 37—Well, the Lefl-Roaders take a long mental journey; perhaps they are as wishful in their thinking as the detour-lads. And perhaps, don't you like to think so?, there is, after all, a middle ground, not yet perceived, in the fog ahead. Today, we can't chart it by logic. Fortuitously only will it be found.

Nevertheless, veering now Left, and now Right in our thinking we may speculate on the probabilities of chance, and reach one or two reasonable conclusions: The present act is not apt to deal a death blow to Capitalism, or to "socialize industry", as long as it is captained by its present personnel. That personnel was chosen by the President. Only a radical change in national circumstances will alter the colour of the personnel, and place this potentially radical instrument in radical hands.

But what if there is no substantial or sustained improvement in business?

Then the use of governmental funds to create employment and the increased control of industry must be augmented in intensity and extended in time. Social demands, my masters, will admit no alternative. Moreover, even if boom times, like an erring wife, comes back to Capitalism's home, so much improvement in productive technique has been made since the beginning of the Depression that a restoration of the cock-eyed quantitative levels of '29 would still find us, Recovery Act and all, with 7 millions of unemployed workers. The need for planning in anticipation of this demands continuation, and challenges intensification of government direction in Industry. Again, should prosperity quickly, or slowly, or partially return, as a result of the National Recovery Act, is it not reasonable to suppose that labor, government, even business will look upon it, in essence, in theory, as a lovely goose that laid a golden egg, and not be in too much of a hurry to serve it up for the rugged individualist's dinner?

It is inconceivable that the effects of the Bill on recrudescent prosperity should be negative, but even were this so, as long as the return is coincident with the administration of the Act, the Act will receive, in the popular mind, a good deal, if not most of the credit —another guarantee of its survival.

Anyway, all logic leads to the conclusion that this Bill, for one reason or together, will remain—modified, evolved, or in substitution, a vital force in the governmental procedure of these United States; will survive, in any eventuality, long enough profoundly to influence our industrial mores; and that that survival, although conditioned by changing political bias, and economic trends, spells the end of the industrial skullduggery, of the batblind laissez-faire economics so dear to us in the twenties—and so costly to us in the thirties.

So, although at best it is an inconclusive verdict—unpopular with both soft-headed talking Socialists and hard-hearted working Capitalists of the extreme positions—it is safe to assume that Capitalism, for the next few years, at any rate, will be hanging round our factory doors—on Parole.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now