Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA poke at poker faces

PAUL CALLICO

There seems to he no dictionary or reference hook that offers a proper definition of the strictly American phrase, or descriptive name—''Poker Face," hut it is popularly supposed to indicate the bland, cold, impassive face of the expert draw poker player, at the critical moment when he is examining the cards that he has purchased in the hope of improving his hand.

You may well imagine that if you are the nervous, emotional type who blushes, grins ecstatically, swallows his Adams apple, and begins to bead moistly at the upper lip, upon discovering that the one card draw is really a fifth spade, that you are going to be a popular guest at poker parties as long as your bankroll lasts. 1 he average poker player when he is drawing cards contorts his features into what looks like an advanced case of Verstopfung in the fond belief that he looks like an old Mississippi River gambler. However, you get the idea. And this is not an article on the fine old game of Poker, but on sport, on poker faces in sport, and what I am about to say is that you can have them.

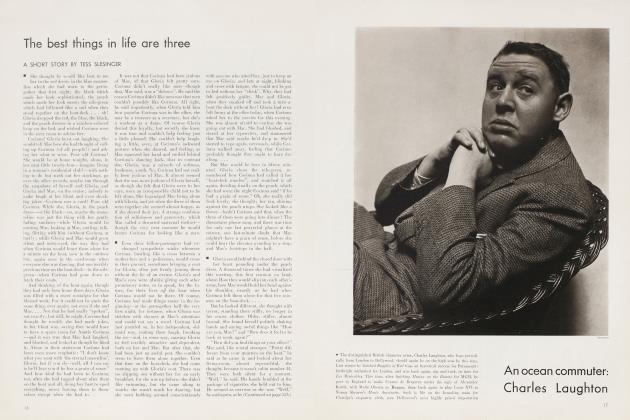

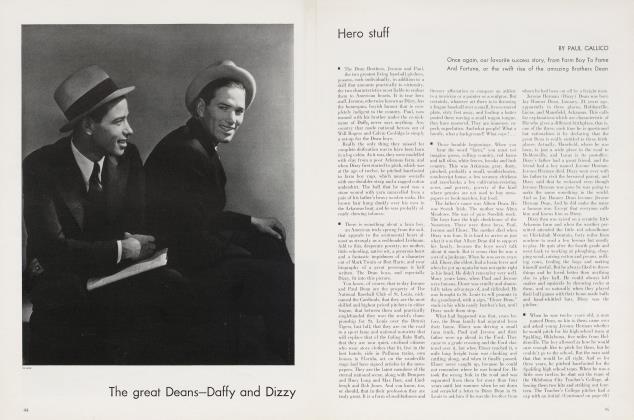

It all seemed to have begun back in the riotous days of the Golden Decade when all athletes, amateurs and professionals were heroes and the sports pages were soaked with the gay colors of careers and personalities. They were the days of Dempsey and Cobb, and Ruth, and Tilden and Johnston and Weissmuller and Sande and Rob Jones, and Ederle and Lenglen and er . . . Helen Wills. Helen was a cute little girl from California with pigtails who could outbat all the other girls at tennis. Helen didn't have any color. She would come on to Forest Hills with her Maw, whop the lady tennis players and whop them good, and then go back to California. We were selling color in those days and selling it at nice prices too, and color we had to have. And nicknames. Those were the days of the Four Horsemen, and the Wild Bull of the Pampas, and the Manassa Mauler, and Rig Bill and Little Bill. One of the brighter young men watched Miss Wills playing through a tournament, apparently without changing her expression and named her Little Miss Poker Face, and Little Miss Poker Face she became and remained.

Now the actual truth of the matter is that while Miss Wills, now Mrs. Moody, appeared to have a cold expressionless face during play and one that completely masked her emotions, actually she hasn't. I proved this to myself one time many years after the nickname had become firmly fastened to her by taking a pair of powerful field glasses into the Marquee at Forest Hills and bringing her face up so (Jose that I could see beneath her inevitable eyeshade (which became first her trademark, and then a national fad) and in a rather tight match with an English girl. I read practically every emotion on her lovely face—alarm, pain, exasperation, delight, laughter and fear.

And still some years later, one glorious sunlit afternoon when we were driving around San Francisco she told me the reason why she wore the famous eveshade. In this instance, the simple explanation wasn't the correct one. It wasn't to keep the sun out of her eves, hut to keep her opponents from reading her face and taking advantage of what they saw written thereon. If anybody ever had Helen Wills on the run in those days when she was unbeatable, they never knew it.

The damage, however, had been done. The dead pan had been introduced in sport as something admirable. Professional and amateur athletes enlisted under the sign of the cold fish. You see them still going through terrific competitions coldly, unemotionally, expressionless. They give me a pain. If they only knew it, they give the average spectator a similiar ache. Because the whole psychological basis of spectator attendance at sports events, is vicarious participation.

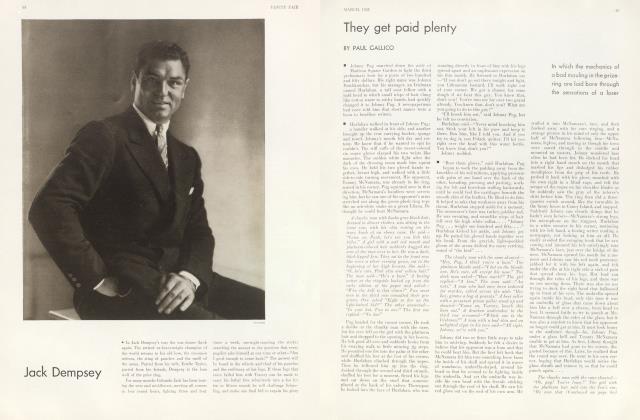

Some of the greatest thrills I have ever had from watching sport have come from catching some single, fleeting expression on the face of an athlete that told me a story. There was the night that Tunney and Dempsey fought for the second time in Chicago. Dempsey knocked Tunney down in the seventh round and then tried to knock him out.

Tunney, desperately hurt, ran, that is, kept ever moving backwards, to save himself. Dempsey chased him. Tunney's legs, even though numbed by the paralysis of the chin punch, were young and strong. Dempsey's were the tiring, inelastic limbs of a fading athlete. Around and around the ring they went, Tunney, his face to his foe, fleeing,—Dempsey, dark, scowling, lusting for victory, following. Finally, Dempsey stopped. He could go no further. I watched his face. He stood staring at Tunney with contempt, and, with his hands, motioned Tunney to come in and fight. Tunney was too smart. And then there came into the eves and face of Dempsey such a strange and bitter look. It was self realization. He was in that moment a has-been. The championship had been in his red leather mittens, and HE had failed to take it. HE was no longer as good as he had been, The Dempsey of five years before would have caught his man and finished him. What a helpless, despairing, dramatic look. I remember, that sharply, and painfully, for a second, I felt everything that Dempsey felt. That look had taken me into the ring with him, and 1 lived all his weakness and discouragement, and his tremendous will to win and the tragic inability to do so.

Continued on page 57

Continued from page 18

There was Max Baer in his amazing and puzzling failure to defend his title against the third rate Jimmy Braddock in the Madison Square Garden Bowl, a few months ago. In the early part of the fight, his face was a clown's mask of arrogance, contempt, simulated anger. He was acting every minute. But, along towards the twelfth or thirteenth round, he came out of his corner, and the aggravating, self-satisfied, smart alec had suddenly become a human being with whom 1 suddenly found myself in sympathy. Because on his face was a queer, puzzled expression. The fight was almost over. The man he should have destroyed in three rounds, and for whom he had shown humiliating public contempt was still in front of him and winning the fight. He had failed to hit him solidly, failed to hurt him, failed to outbox him, failed at everything, lie was asking himself —"My God, how did this happen? What SHALL 1 do? What CAN 1 do? Why is this guy still here? I should have knocked him out in a round. I AM a great hitter, hut there he is. still. . . ."

At that moment, my anger against Baer vanished. We were sharing a common experience. I had once, twice, many times taken an opponent too lightly, thought that I would wave my hand and end the matter. And I remembered how I had felt when it was too late to do anything about it. A thousand voices had called to me"Sucker . . . sucker . . . sucker. . . ." They were calling to the losing champion now, the same voices. He was, after all. my brother. Between us there was a warmth. I felt sorry for him. It was a dull, boring prizefight, but, when I left it, I felt that I had had an experience.

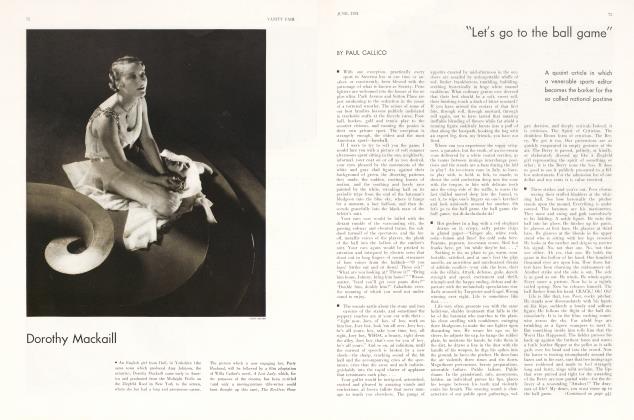

Now there was too, I remember, a certain pennant race for the championship of the National League, last year, in which the St. Louis team beat out the New York Giants in the last few days even though they were not playing one another in the final games. The collapse of the famous New York team was a peculiarly dramatic story and one of vengeance. At the beginning of the season, Bill Terry, the player-manager of the Giants, had ridiculed the Brooklyn Dodgers, the rival Inter-borough team, and, when someone had mentioned Brooklyn to him, had replied to the reporters—"Brooklyn? Brooklyn. . . . Arc they still in the League?"

To have the despised Brooklyn team turn out finally to he the instrument that overthrew the Giants in the last two games and knocked them out of lead, pennant, and World Series money sounds like the invention of a Hollywood script writer, but that is exactly what happened. Thousands of fans jammed the stands as the Brooklyn hatters knocked the Giant pitchers from the field, and the Brooklyn pitchers befuddled the Giant batsmen, and their war cry was—"Is Brooklyn still in the League?" When Bill Terry, the manager who had spoken that boomerang sentence, came to hat, to pop up or ground out, he was hissed and booed, not only by the Brooklyn, hut also the Giant, fans.

I don't think Terry's expression varied a shade the entire two days. When he came to hat his face was a mask, and a mask it remained. There was little sympathy felt for Terry. And yet one little gesture on his part would suddenly have melted that vast gallery of haters and sent them home, enriched by a real sensation of having participated in the series. 1 remember sitting up there in the press box and watching him face blast after blast of public disapproval, without moving a muscle and finding myself vaguely dissatisfied and ill at ease. I wished that he would do some little thing to show that he was experiencing a human emotion. Had he just held his arm in front of his face for one moment in mock-shame and then grinned a little, he would instantly have been en rapport with every soul in the park. We would have felt—"Never mind, old boy! WE know how you feel. We've had many a wisecrack of our own come hack and pin us. . . ."

Sports spectators are desperately and pathetically eager to share the thoughts and emotional experiences of their heroes. One little revealing look, one passing gesture will please them more than perfect performances and winning scores. To see Babe Ruth hit a home run in a World Series has always been a great thrill. But still it remains nothing hut a fine mechanical performance. Eye, judgment, strength and experience combined, turn the trick. But not one of the forty odd thousand at Wrigley Field in Chicago will ever forget the World Series game between the Yankees and the Cubs, when with two strikes and two halls on him, Ruth pointed with his hat to the centerfield fence and then hit the next hall out of the park on exactly that line. The home run showed the kind of ballplayer, but the preliminary gesture revealed the man. The utterly mad, courageous, impudent, self confident swashbuckler. The nerve of him! And to get away with it! Friend and foe alike came away that night loving him for it. That was the kind of thing we would do—if we could.

When Fred Perry, the great English tennis player throws his tennis racquet high up into the air after winning a difficult championship, or hows his head in disgust at gumming up a shot,

I am delighted at being permitted to share his experiences. If I were to heat Jack Crawford, you can damn well bet I'd throw my racquet clean out of the stadium in celebration.

This sort of thing is often miscalled color. It is something quite apart. It is more the human, natural touch, the courage and the ease to give away to emotions as we all do. Your so-called good loser with his phony smile and warm, what-a-good-sport-I-am handclasp always makes me a little ill. My kind of guy is the loser whose attitude is—"Well, you louse, congratulations, you heat me all right, hut if you think I like it, you're crazy. I feel awful.'"

Continued on page 60

Continued from page 57

William Lawson Little, British and American amateur golf champion, and Enid Wilson, the fine English girl player, may both he called colorful, but I wouldn't walk a hole behind either unless f had to, because, if I want to see a golf hall hit perfectly, I can go out to any golf hall factory and ask them to let me watch their electric driving machine for an afternoon. They shut me out. Lawson Little looks the same sinking a chip shot from thirty yards off the green as he does when a two-foot putt rims the cup and stays out. Miss Wilson never raises her head or changes her expression from first tee to last green. But they must he glad when they are lucky, and mad when a had break spoils a good shot. If I have a rooting interest in them, for or against, I want to rejoice with them or sympathize with their trouble. In a nutshell, if THEY don't seem to care, why should I?

There was, for instance, the simple and unreported incident of Gene Sarazen finishing one of his rounds at the recent Open Championship at Oakmont. There were some two thousand people banked around the home green. Sarazen had had a terrific struggle all the way around, fighting the course, fighting himself, getting his pars the hard way. He came in needing something like a four for a seventy-five. His second shot was on the green but fifty feet from the pin. He took a putt and found himself with a six footer left. He putted again. The hall ran up to the hole, looked in, changed its mind, rolled around to the side, hesitated a second, and finally collapsed in the side door. The crowd gave a polite cheer. Sarazen then picked the hall out of the hole and drew his hand across his brow, dashing away imaginary drops of perspiration. An absolute ripple of complete understanding ran through that crowd, clear and unmistakable. With one little move, Sarazen had let them in that it had been a tough round. That the whole business had been like that last putt. That he never thought it was going down. That he wouldn't have been surprised if it hadn't. That he was damned glad it had gone in and that he was still more glad that, for that day at least, it was all over. Winning or losing, the galleries will always trail the Sarazens, the Hagens, the Craig Woods, and Jimmy Thomsons, and Paul Runyans. They all have the knack of letting the spectators play along with them.

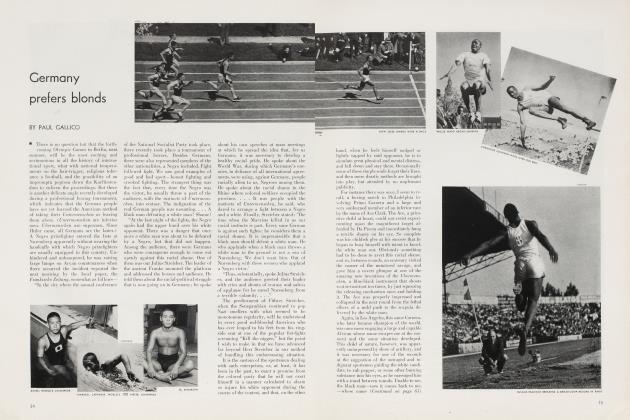

Joe Louis, tHe new colored knockout sensation, features a poker face, cold and expressionless. When the Brown Bomb exploded on Camera and left Old Satch bloody, rubber-legged, with his eyes hugged out in pain and astonishment, the explosion was limited to Joe's fists, His face didn't blow up even a little bit. Even when his glove was raised at the end in token of victory, he showed no particular joy. His features remained set, like plaster. The crowd will never warm to him as they do to little Tony Canzoneri, who, without tipping his opponent, somehow has a way of letting the audience know how things are going with him. For all his faults, Primo Camera is loved in the ring because his huge physiognomy never hides anything: anger, joy, disgust, panic, bewilderment, a pathetic combination, is always writ there plain to he read, and touching ready chords of sympathy. He does manage to look so big and helpless for all his size and strength. That is an art.

And so 'raus mit your Dead Pan Looies and Poker Face Petes and Stone-Eyed Sams. They aren't playing the game and giving money's worth. When 1 buy a ticket to see you perform, I'm paying to see you writhe if you lose. So never mind the icebox 6tare. Squirm a little and give the boys and girls a treat. And find yourself, strangely enough, loved for it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now