Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe venomous Doctor Palmer

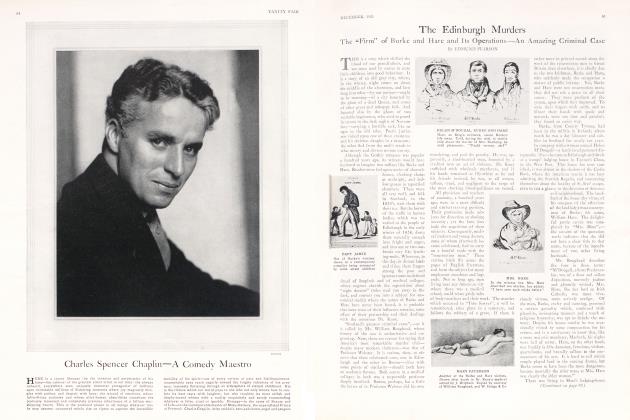

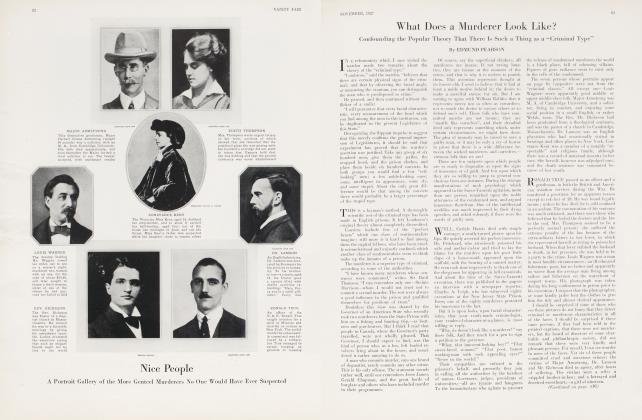

ANOTHER FAMOUS MURDER CASE BY EDMUND PEARSON

EDMUND PEARSON

■ "When a doctor does go wrong, he is the first of criminals. He has nerve and

he has knowledge. Palmer and Pritchard were among the heads of their profession." —Sherlock Holmes in The Adventure of the Speckled Band.

That William Palmer, the doctor—holding a surgeon's diploma from Bart's— should turn out to be a murderer filled his community with a mild dismay.

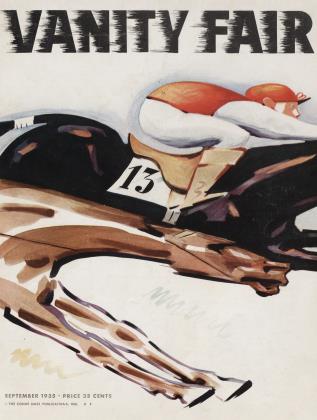

But that William Palmer, the sportsman, the racing-man—owner of Goldfinder and The Chicken—that this ornament and devotee of the "Sport of Kings" should have murdered not only most of his family, but also some of his associates of the turf— this caused Great Britain to rock with horror. It spread consternation to the farthest reaches of the Empire, and makes venerable judges and prelates, even today, discuss the exact words in the racing phrase used by Palmer at the dreadful climax of his career.

Palmer was a bad boy. In his native town of Rugeley (not far from where Burton is built on Trent) when he was a rosy-cheeked nipper in nankeen trousers, he was cultivating a pious exterior, to conceal his juvenile deviltries. He was always "very respectable" on the surface.

■ "Mr. Palmer a murderer!" exclaimed the folk of Rugeley, when the truth came out. "Why, he used to make responses in Church louder than anyone else!"

Not only louder but holier—such was his voice during the service. His mother—not, perhaps, a qualified expert as to virtue— referred to her son, to the end of her days, as "my saintly Bill."

It may be true that the saintly Bill, from scratch, carried the handicap of bad blood. He was one of seven children, to whom their father left seventy thousand dubiously acquired pounds. Their mother was the heroine of several infragrant scandals. In the flock of seven brothers and sisters, there were three black and four white sheep, so the matter of heredity is puzzling.

William's first employment, appropriately, was with a firm dealing in drugs. His embezzlements from them were made up by his mother, and he escaped punishment. At about the age of eighteen his apprenticeship to a surgeon was marked by the persistence with which, as often as he could, he robbed men of their cash and women of their virtue. The surgeon soon decided to part with this bright young man.

Scandals did tend to cluster around Palmer, and it may be an unfriendly estimate which ascribes to him the unauthorized paternity of children by fourteen different women, other than his wife. The historians—and they are many—differ about some of the incidents of his career. Thus, Dr. George Fletcher says that it is not proven that Palmer was guilty of the murder of his uncle; of a racing friend, named Bly; and of a man named Abbey. Miss Tennyson Jesse, on the other hand, gives good reasons for suggesting that the Bly business was suspicious.

That his medical attentions to one man consisted of plying him with brandy till he died (carrying on, the while, an affair with the man's wife) would be grievous news, if it did not emphasize William Palmer's one conspicuous virtue. He touched none of the brandy himself. He was practically a teetotaller. Charged, during his short life, with almost every known vice and crime, he was never reproached for drunkenness.

And he observed the conventions, the little decencies, of life. The wide mourning band, on his hat, in the portrait, is a token of respect for some relative or friend he had just helped across the dark river.

By the age of twenty-three he had studied medicine at Bartholomew's Hospital; received his diploma; married a girl named Annie Brookes; and set up his household in Rugeley. Patients did not come to him, nor did he care. He had an income, and if it failed, there was his mother who seemed delighted to submit to his swindlings. In Staffordshire, the chief concern of mankind was the horse, and Palmer's knowledge of that animal was far from despicable. Before he was thirty he was celebrated on the track, but his grand manner of life, as well as some racing misfortunes, had landed him in difficulties which he tried to repair through the money-lenders.

Before coming to the authentic case which made Palmer famous not only in the annals of the turf, but in the history of legal medicine, it may be well to glance at the pack of little scandals which barked around his heels.

His intrigue with one Jane Burgess is attested by a packet of letters still in existence. They are said to be very shocking, and remain unpublished. A mild attempt at blackmail, by Miss Burgess, seems to have been the only crime connected with this affair. Dr. Palmer and Miss Jane Mumford's baby "died after it had been visited by him." Of Dr. Palmer's five legitimate children, four died in infancy. Of course, untimely deaths of children, in the 1850's, were frequent. Still, it is said that the Doctor's way with babies was to dandle them on his knee for a while, after which they usually went into convulsions and died. Poison on one of the Doctor's fingers; the finger then covered with powdered sugar, and the infant allowed to suck the finger— this, it is hinted, was the Doctor's method.

Mrs. Thornton, the Doctor's mother-inlaw, was induced to visit him: she died within fourteen days. There was a horsey person named Bladen, to whom Palmer owed £800. Mr. Bladen became a houseguest at the home of the Doctor, and Mr. Bladen, in a very few days, was both dead and buried. A funny old doctor named Bamford, who was over eighty, and perhaps senile, accommodated young Dr. Palmer by signing death certificates whenever asked to do so.

Palmer's creditors contracted a habit of sudden death. Years afterwards, a conversation between two book-makers was overheard on a train. One of them, named Kirby, described a visit he once paid to Dr. Palmer, to collect a debt of £25.

"Sez 'e, ' 'Ave a glarss of sherry, Kirby.'"

"'I shall be glad to 'ave one, Mr. Palmer,' sez I, 'if you'll join me.'"

"'No', 'e sez, 'thank 'ee, Kirby, I never drink sherry.'"

"'No more don't I, Mr. Palmer,' I sez."

"'Come an' 'ave a little look round my farm,''e sez, 'I've got some nice little pigs to show you.' "

"An' when we was lookin' at the farrer, 'e sez: 'You've been so good in lettin' that little account of ours stand over, I'll 'ave my cook send you one of those sucklin' pigs all ready to roast.' "

Continued on page 64

(Continued from page 31)

" 'No, thank 'ee, sir,' I sez again."

"I worn't goin' to drink 'is damned sherry nor eat 'is pizened pig."

For the murders of his wife and his brother Walter, Palmer was actually indicted. Mrs. Palmer was insured for £13,000 and died within six months. On the life of Walter Palmer, the Doctor tried to secure £82,000 insurance; he did obtain £13,000, but soon after his brother's death, there were other and even more startling things to be explained.

A young sportsman named John Parsons Cook had become Dr. Palmer's chum. They went to races together and made many a bet. Cook owned Polestar, brother of Palmer's Morning Star. Assignments of wagers, and other involved business, would cause Cook's death to be profitable to Palmer, at a time when he was in dire need of cash.

The financial transactions of Palmer and Cook baffled many an accountant, and the physical sufferings of Cook, during certain midnights of November, have caused learned men to write, literally, shelves full of books. To reduce a complicated story to the simplest form, it can be said that Palmer and Cook put up together at a Shrewsbury inn with the sinister name of The Raven, and that a day or two later, in Rugeley, Cook stayed at a hotel opposite Palmer's house. At these places Palmer gave bis friend brandy and water, and coffee, and soup. At The Raven, and still more at the Rugeley hotel, Cook was very sick. Palmer was in and out of the bedroom, and the drinks he administered caused anything but relief.

Cook's illness took a most distressing form, and the recital of his agonies, as witnessed by chambermaids and others, constitute famous chapters in the lore of toxicology. Something of the sort was described, not with entire accuracy, in Mr. Kipling's "Reingelder and the German Flag," when the unfortunate scientist was "doubled into big knots, and den undoubled, and den redoubled mooch worse dan pefore." For the symptoms "vas all dose of strychnine." And Dr. Palmer had recently made two purchases of this fearful, but—at that time—littleknown drug.

By special Act of Parliament, Palmer was tried in London, as the feeling at Rugeley imperilled the chance of an impartial hearing.

Never did doctors have such a good time, or dispute one another so flatly.

Old Dr. Bamford, of course, had attributed Cook's death to "apoplexy." Dr. Palmer, the scientist chiefly interested. had done his best to fog the paths of the investigators by jostling their elbows at the autopsy, and trying to upset the jars containing specimens selected for analysis. The Crown experts testified that thetetanic convulsions of the dying Cook were those resulting from strychnia. But antimony and not strychnia was found in the body, and whether this is explained by Dr. Palmer's jostlings, or by what, it opened the door for the physicians called by the defence.

These gentlemen, in one way or another, referred to Mr. Cook's "inherited delicacy"; to his "mental excitement"; to syphilis; to apoplexy; arachnitis; tetanus (both traumatic and idiopathic) ; to angina pectoris; and to epilepsy.

There was enough erudite conversation about poisons to furnish forth three or four detective novelists. One court stenographer got something into his notes about "exhetwich"—a venom still unrecognized by science. In another place this appears as "tschk." Plainly, a Russian word. The world's knowledge of strychnia was widened, and there emerged the interesting fact that from strychnos toxifera come those delightful lethal drops called woorara, better known to the tellers of tales as curare, which, as the justly popular arrow-poison of the South American Indians, has done its deadly work in a dozen novels. This may or may not be allied to "the hellish oorali" mentioned, in a poem, by Lord Tennyson. I merely offer the suggestion.

Perhaps, in the words of the policeman in "Michael and Mary," Cook was murdered by "one of they secret Horiental poisons, wot leaves no trace." Murdered he was, and by Palmer, and the jury, after a long and careful trial, so decided. When William had been convicted he sent a note to his solicitor, referring to the powerful argument against him made by the Attorney General, Sir Alexander Cockburn. He wrote:

"It was the riding that did it!"

And this by no means remarkable epigram has, for some reason, discernible only in the British Isles, been as carefully treasured as that other much-touted quip, in Meredith's "Egoist," referring to Sir Willoughby Patterne's possession of a leg.

Dr. Palmer's stud was sold at Tattersall's and Prince Albert the Good bought the mare, Trickstress, for 230 guineas. And the Doctor, himself, was taken back, "for the sake of the example," to his own county of Stafford to be hanged.

He had been implored to confess, and clear up the puzzle as to bis methods. To these requests, he only remarked :

"I am innocent of poisoning Cook . . ."

But he added: ". . . by strychnia."

This left everything where it had been. Perhaps, at the final moment, Palmer's professional pride was touched. Perhaps, like many murderers, he felt a sense of injustice, because the manner of the crime remained undetected. But strychnia or something else was a point of wholly technical interest to the unfortunate Mr. Cook.

The day of the hanging followed a rainy night; there were puddles on the ground and the little Doctor minced delicately along on his way to the gallows, carefully avoiding the mud and muddy water.

England's chief hangman, Calcraft, was not present, and the work was done by a local yokel, who worked at cut rates. He was named Smith—a tall fellow, in a velveteen jacket, loose trousers, and a billycock hat. If Dr. Palmer noticed any slight, he made no remark.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now