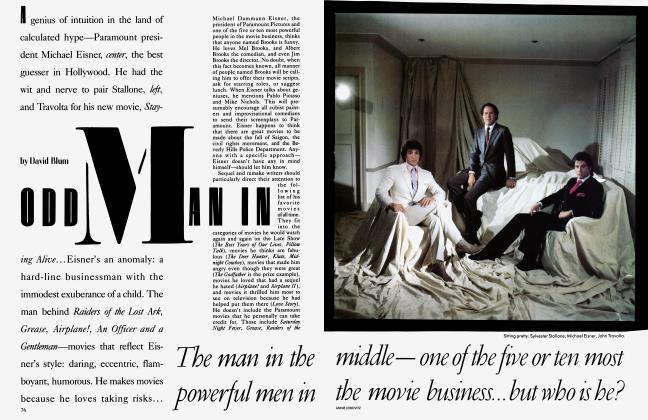

Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWORK HABITS

Bette Pesetsky

A STORY

I have succeeded,” my father said. “So can you. I could tell you such glowing tales of my success. But I’ll lay my cards on the table. Nothing is permanent.”

My father sat me down. “It happened,” he said, “when you were seven. Can you be expected to remember from when you were ⅛ seven? Your brother was fifteen. What happened to him later I put right at their door—right at the door of the Empress Chocolate Company—‘Sweetest Sweets in the Ozarks.’ In March when the spring water ran the coolest, they pink-slipped me like a candy surprise. My life will henceforth go down unknown paths, I said to myself. Meanwhile, I had to go home. I was consolidating it all in my mind, the reorganizations, the red columns, the declining sales, the American sweet tooth gone cavity-free. To this I added the factors of my age, my wife, my not fully grown children.

“I came home. We had dinner. We had breaded veal chops, mashed potatoes, peas, salad. Your mother cleared the table, no one helped. She brought in the poached pears, the coffee. In the living room in a glass bowl were the Empress’s finest chocolates—dark, with hazelnuts. I had the whole event planned, net profits, gross losses, escrow accounts. But instead I sipped my coffee—black, unsweetened—and blurted it out. They let me go today, I said.

“Your brother looked at me. He had the hardness of city babies. Do we have for bread and so, or not? he says. Of course, I say. As I edged towards the door, torn with pain, you all shrieked and tore at my clothes. Where are you going? you shouted.”

My father kissed me, a kiss of luck. I went into success. Three jobs in fifteen years. I went from Chicago to Detroit to New York. I moved up, I moved up into middle management. But I had hopes, dreams, thoughts of further promotions. “It’ll come,” my husband said. My husband was very loyal. “They’ll recognize your worth.”

Sometimes I wrote out a letter of resignation. But I didn’t submit it. I stuffed it into my purse and took it home to burn.

My friend Arthur and I once collaborated on a booklet called “How to Stay Awake in Meetings Without Dancing”—it was rather funny. We duplicated it and passed it around at the office. It was much enjoyed and got us into no trouble. “You were lucky,” my husband said.

Does it bother me that I now have only a daughter for the future? Not at all, my father wrote. Trust people. Once I got on a bus without any change. I stood there holding a dollar bill. Excuse me, I said. Does anyone have any change? My voice was low, apologetic. I was young, not yet assertive. No one moved, no hand slid forward. Listen, I said, I must stay on this bus. I’ll be late for work. I might lose my job. One set of hands moved slowly to purse, opening vinyl purse made to look like leather with pretend straw handles. From a woman, old, vain. Here is the change, she said. Bless you, I said.

I went to work every day. Middle management goes to work every day. In the genesis of the week, I came alive in time for Tuesdays. What happened on Tuesdays? On Tuesdays the section supervisors met at ten. We sat there, a dozen of us. They fed us coffee from a soupscented urn and glazed doughnuts. One of the section supervisors did imitations. He did Clark Gable. He did Charles Boyer. He did Jerry Lewis. Sometimes district supervisor Barlow conducted our meetings. We heard from him a lot about feedback and interface. Arthur can’t stand him.

“God, it’s him today,” Arthur whispered to me. “Want to interface for lunch? Feed your face instead of your back.” I would have liked to hit him before I started to giggle. Whenever I said shut up, everyone heard, no matter how low my voice. So I stepped on Arthur’s foot instead.

“Wait,” Barlow said at the end of the meeting, the finger pointing at me.

Arthur made a face. “Zap time,” he whispered.

They were homing in on my department. They were asking me to fire Dorothy.

“Today,” Barlow said.

I nodded.

Actually, the firm discharged people quite regularly. How were they chosen? I had once asked Arthur. “A formula,” he had said. “Productivity plus seniority times spit in the air— that’s how.”

Dorothy had the third office down the corridor from mine. She had been with the company for about a year. I looked over her personal data in my folder. She was one year younger than I. She was divorced; there was one child.

My father on the telephone. “We were selling tiny ivory elephants. He had the elephant people there. Deliver, he said.”

It was eleven-thirty when I returned to my office. Arthur had always advised, “Fire them after lunch. The full stomach makes them soporific.” I never turned my back on advice. I stood at my door and looked down the corridor. No activity. All the doors were closed.

I waited until ten past one, and then I dialed Dorothy on the intercom. “Would you step into my office, please,” I said. On my desk was the envelope with the check. We gave money instead of two weeks’ notice. They didn’t like anyone to hang around, a disturbance, people took sides.

Dorothy came in. I had invented a mythology about her. Her skirt was wrinkled. Dorothy did not care. She did not pull it tight when she sat down. I visualized her as ugly, preferably with warts. Two warts on the nose. Hell, Dorothy, I would have said. You’re canned.

There stood Dorothy burdened with the customary pad and pencil. In the past two years I had had to fire four people. One of them, a small blonde, had immediately slumped back in her chair. “My father is sick,” she said. “Did you know that? How can you do this when my father is so sick?”

Dorothy was no amateur in life. She must have seen what was coming, because she refused to take a seat. Perhaps I was tapping the envelope. She just leaned back against the door and crossed her arms. Her expression was cynical, weary, unfriendly.

“I’m truly sorry, Dorothy,” I began. “But the economy, you realize. There have been cutbacks all around. I will certainly give you a reference. Have them write directly to me.”

“Yes,” she said and held out her hand.

I gave her the envelope, and she said nothing further but immediately left the room, closing the door quietly behind her.

Only once before had it been that easy. A man had stood in Dorothy’s spot, and said some words not clearly heard. “What?” I had said. But he only shook his head and left.

I had delayed my lunch. I was eating my sandwich when Malverne, the reception-area office manager, knocked on my door. “Gone,” she announced. “Dorothy left. She just put on her coat, said so long, and walked out.”

“So?” I tasted lettuce, the bitter ends of roast beef.

“It’s her room.’’ Malverne’s cheeks were reddened by the pain of holding back. “She didn’t clean out her room. And that room is being borrowed by Fiscal this very afternoon.”

I felt the blame. Dorothy was in my department. I could have ordered Malverne to clean out the room. The old fox had expected that, hoped to forestall it by complaints.

“Get a carton,” I said. “Find a carton somewhere. We’ll empty into it. Dorothy will probably come back to get her things.”

After I finished eating, I walked down the corridor to Dorothy’s office. She had abandoned ship. Papers on her desk from the morning’s assignment. Pen uncapped and two sharpened pencils near the lamp.

Malverne was sly. The carton was already by the desk. Malverne was not. I stacked the papers from the top of the desk into the In basket. Work that I would assign to someone else. This was going to be simple. Three of the drawers were stuffed with supplies, nothing else. I bequeathed them to Fiscal. I had only to clean out the top side drawer— the usual personal junk. Towards the back of the drawer a blue spiral notebook, not office issue. I opened the notebook to the first page—My Life Story! Now that I would save for later.

Not enough in the desk to require a carton. I slid what there was into a large manila envelope and labeled it Dorothy. I took the envelope back to my room and put it on the shelf behind the desk.

I stiffened my back and went home. “I slit a throat today,” I told my husband.

“It’s often a question of retrenchment,” my husband said. “You have to swing with them.” He shook his head. “You have to swing with them.”

My education was not just in the school of life, my father wrote me. I was for many years a night school student. But I worked even through the hardest times. For instance when I worked for Kulmisca. I went one day into Mrs. Kulmisca’s office, thinking in my mind that of all the ways, the open confrontation was the best. I was promised a summer job, a fulltime summer job. Now to face no summer job and the loss of even the few hours I was paid. Mrs. Kulmisca, I said, I fail to understand. No, that is not the best way to put it. I understand too well. I have been found to be dangerous. I will never tell. Didn’t I say that I will never tell? I understand, Mrs. Kulmisca, that you do not know me so well, but I will never tell. My word is enough. I have an understanding with nature—no, hear me out. I grew up on a farm. Farm as it was. Not farm as it is. It was outdoors, there was so little machinery. Mrs. Kulmisca, I can be trusted. Didn’t I say that I would not tell?

The girl on the flying trapeze went back to work. What was I going to do? I was going to open that notebook. My Life Story! Who could pass that up? A chance at someone’s life. Afterwards, I might joke about it with Arthur. “An addition to my voyeuristic past,” I would say. “The past of a peeker and a prier.”

Twice I had read secret diaries. A friend trusted me. The diary was always on top of his dresser. I read it, parts of it.

But Dorothy was different. I didn’t really know Dorothy. I took the notebook from the envelope. Not a lined notebook, an artist’s notebook. I flipped the pages, a bunch of circles and lines. I concentrated.

I turned to the first page. Dorothy had drawn three circles positioned to form a triangle with lines ending in arrows connecting each circle. The lines were so fine and sharp that she must have drawn them with a mechanical pencil.

The top circle was labeled Me, the one on the left was Mama, and at the right Papa. She was certainly beginning at the beginning—the place where you say I was born in a little log cabin.

An Artist’s View of Life! An Artist Looks at Life! My Life as an Artist!

Her life, my life. I hunted in my desk for my clear plastic metric ruler. I used it to measure Dorothy’s lines. Each line was exactly fifty millimeters. I took a piece of paper from my wooden memo box. Using the ruler I drew my first line and then the circle freehand. Hers were better. The point of my number two pencil dulled quickly. I sharpened the pencil for the next try, one line, resharpened the pencil for the circle, next line, resharpened.

In my top circle I printed Me, to the left Papa, on the right Mama. Was Dorothy an only child? Did my brother count? He had gone, disappeared into dark ways, a pioneer in misery. I mourn for him, my father had said. But it’s like he never was.

Now the setup of my family tree wasn’t exactly Dorothy’s. Instinctively, I had done the reverse. Mama second in line. Did it matter who came first? Facts were facts. She didn’t seem to be around all that often. Faulty memory, perhaps. There I was in Union Station, a little girl of five or six, and bawling my eyes out as Mama’s back retreated from me. I called out, I begged. I was held back by an aunt who pinned my arms tightly. In the distortions of childhood, Mama might have been going nowhere, Mama might have left me to purchase tickets, I might have been accompanying her. There might not have been a lover waiting for her on the other side of the pillar.

I turned the next page. Dorothy had drawn three large circles. Beauties those were—no freehand scrawl of mine would come close. I was either going to do this properly or not at all. I dialed Malverne on the intercom. “Are you going out for lunch?” I asked.

Her hesitation was deliberate, but then she was aware that if she said no, I must expect to see her sitting there with sandwich and waxed paper and cartons. “Yes,” she said. “Yes, I am.”

“Would you mind,” I said, “taking a few extra minutes and stopping across the street at the office supply store and buying me a compass.” “What?”

“Ask the man,” I said testily, “for a compass for making circles.”

I had felt the tiny holes in the paper where Dorothy had placed the point of her compass to make the three circles. She used the same names on each circle, but the order differed. Ann, Mary, Sue, John, Dorothy, Dick. Mary, Dorothy, John, Sue, Ann, Dick. John, Ann, Dorothy, Sue, Dick, Mary. Was she saying that the sequence did not matter in first circles? No necessity for boy, girl, boy, girl.

I needn’t change the names for my circles, those names would do—I just added my own. Weren’t all children’s names alike? I was certain that those people had existed for me, that we had joined hands and moved in a clockwise motion—first John then Ann then Sue then Dick then Mary then I. Playing our games with no self-consciousness, no giggling, just a chant culminating in the command “All fall down!”

I had Malverne’s compass. Brittle yellow plastic instead of metal. I believed that she must have selected that one on purpose. As if perhaps she might not be repaid for the metal one. Nevertheless, the yellow one did just as well, made circles of the proper circumference for my small sheets of paper and my sharpened pencils.

My father called me on the telephone. “I was in construction at the time,” he said. “Now maybe I’m mistaken, but I never saw a mansion or, say, a really big house downed by a tornado. Tornadoes go a lot to developments, to mobile homes, whipping through poor folks like the caress of God. There was some loss of life. The tornado came down about six in the morning. It took the back wall of the Lancelot Apartments complex. Made stage sets of the place. Drive by and look, those rooms seem less than lifesize. The police came and yelled, You all get out of there. We waited until they had gone away, sirens blasting good morning, and then we came right back in to sign up the customers.”

On Dorothy’s next page were two interlocking circles. So we’ve gone into our group phase, have we? All of the names of the first circle were repeated with a few additions, but now all the girls were on one circle and the boys on the other. Ann, Mary, Sue, Cele, Audrey, Dorothy. The circles looped, and John, Dick, Roger, Yale, Frederick were in the second circle. A lot of the same names. This girl had real stable relationships. Didn’t she ever move? Jesus, my mother used to say, I sign up for ballroom and tap at Arthur Murray, canasta at the Legion hall, and it’s covered wagon time again.

“Can you remember your childhood friends?” I asked my husband that evening.

He was reading, thinking, he was annoyed.

“What’s that?” he said.

But he had heard and answered. “Some. I remember some. It depends. I remember a bully named Christopher.”

I did not remember a bully named Christopher. There was of course the prettiest circle, led by a girl admired for the smallness of her ankles, for the slimness of her wrists. I never belonged to that circle.

On my paper I drew my own circles. Sally, Edith, Roberta, Elizabeth, Barbara. They would have to cross with the circle of Eugene, Nelson, who was my cousin, and Steven. I had no more names. I spaced mine wider, measuring so that they were evenly placed around the circle.

Next came four lines ending with arrows, each line fifty millimeters long, one circle at each corner. Dorothy was lower left, and above was Frederick. Audrey and Yale occupied the other circles. I knew that configuration. I placed myself at lower left, above was Steven, and at the opposite ends were Elizabeth and Eugene. I wore purple lipstick that year. You stay out one more time, my father had said, and you’re going to have to learn to walk all over again. Steven and I behaved as did Elizabeth, whose hair was black, and Eugene. We paired in that season and moved together.

“Do you remember your first love?” I asked my husband.

“My first love,” my husband said savagely, “occurred in Westfield one Thursday night. You remember Westfield?”

“No more,” I said. “I do not wish to hear about those adventures.”

Dorothy had drawn a line seventyfive millimeters long exactly parallel to the bottom edge of the page. At each end was a circle, one labeled Frederick and the other Dorothy. They’d ditched the others, I realized. I measured my line and printed my name in one circle and Eugene in the other. Steven had gone off at once with someone else. What do you expect? he had said. I never asked for any of this, he had said. So when I went after Eugene, I knew what I was doing. But Elizabeth? I had some memory of Elizabeth in disorder, of Elizabeth running.

On the next page the triangle of circles reappeared. The top circle labeled Baby, and the others Mama and Papa. I did the same.

There were noises from Fiscal, the sound of their machines, the complicity of Malverne’s laughter. I must temporarily stop. So I put aside my artistic endeavors, my sheaf of memo paper, my pencil, my yellow compass. I had to face my work. There was a report due the next day that I had not yet begun. After all, I collected a salary. Also, there was a meeting at which I must speak.

I had lunch with Arthur that day, and twice I started to mention the notebook, but I did not. We spoke about our reports.

Get on the good side of clerical, my father wrote. They can fry you. For instance the one at Lonsberg’s. Are you Jewish? she says to me the first day. You look like a Hebrew. Well, never mind. Don’t answer if you don’t want. Now Mr. Lonsberg is a fine one, she says. He is the soul of religiosity. Observant. There’s a list of holidays, I know them all. From Rosh Hodesh to Sukkoth. Days, hours, a fascinating choice. But what I’m getting at, she says, is that you can be here, you see, and Mr. Lonsberg isn’t. To be at work when the boss isn’t is a picnic. Now if you’re like me—a Catholic. Observant. So I get off all my own days. The combination is such that I find to my heart’s content a perfect set of circumstances.

You’d think from that she’s a honey, my father wrote. One month later she says to me, Mr. Lonsberg says go. Yes, she says, he always leaves the telling to me. Mr. Lonsberg checked, and there is no Church of the Fifteenth Pentecostal. Oh, I am so disappointed in you. The very golden goose you have overdone.

Two days later I was able to return to Dorothy’s notebook at the place where I had stopped. Dorothy had drawn a vertical line sixty millimeters long with her name at the end and two circles forming a V shape at the top. Frederick was printed in one circle, and James in the other.

Could we part here? Should I label her slut as my mother would have said? She with her lover.

So I drew my line, the circles to form a V, and printed my Jonathan and my Norrel. I could draw one for my husband, couldn’t I? A similar line with God knew how many circles for names.

I’m no dreamer. I knew the life of hard knocks. I could read the cards dealt for our Dorothy. The husband gone. Now would come the line with more circles—not just two. I’d bet a reasonable sum that James would not last. The divorced middle-aged woman, the child. Goodbye, James.

On the following page was a circle—just one large circle. I was disappointed. Dorothy had been fired too soon. She didn’t have time to finish. I put the notebook back into the envelope. My own sheets were paper-clipped and placed in my middle desk drawer.

I went home to spend the evening with my husband. But he had left a message on (continued on page 120) our answering machine. He was working late. He would not be home for dinner. So I ate with our son, who was fourteen.

Continued from page 85

In the morning I checked my telephone file at work. Dorothy’s home number was still there. Sometimes, people had to be called on weekends, when there was a rush job. It was ten o’clock when I dialed her number. She answered almost at once. That was a bad sign, she was still out of work. I recognized her expectant tone of voice.

I identified myself.

“Yes?” she said, her voice becoming cool at once.

“When you left,” I said, “there were some things—some personal items in your desk. I didn’t know what you wanted done with them.”

“Toss,” Dorothy said.

“You left a notebook,” I said.

“Goodbye,” Dorothy said.

She had hung up. That was not the way to behave if you wanted a reference. I picked up the manila envelope. “Toss,” I said and threw it in the wastebasket.

Arthur took me out for drinks. I spoke to him about Dorothy and the notebook. Arthur thought that it was very funny. “My life as a circle,” he said.

“I had midnight supper with Lana,” my father said on the telephone. “Never drop a contact. They say, she told me, that the factory is sold. Sold, I said. To whom? How? It was not in the papers. Lana smiled. Everything is not in the papers, she said. Powerful people can keep facts out. The factory is a privately held business. The stock in the family. Have a gin and tonic, she said. Cooling. At least you have unemployment. Not me, I said. I’m staying. It’s worse when they push, she said. Push? I asked. Oh yes, she said. They can make you leave. Annoyances. Believe me, it can be done. Then you leave and you have nothing. There is no way they will push me out, I said. I can stand up to anything.”

I took a sheet of paper and drew one large freehand circle. The circle filled the entire sheet, and in the middle I printed ME. I pinned the paper on my bulletin board. According to my calendar, I had a two o’clock meeting, a three o’clock meeting, and a four o’clock meeting.

“Never,” my father said, whispering into the answering machine, “never let anything get between you and success.” Q

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now