Sign In to Your Account

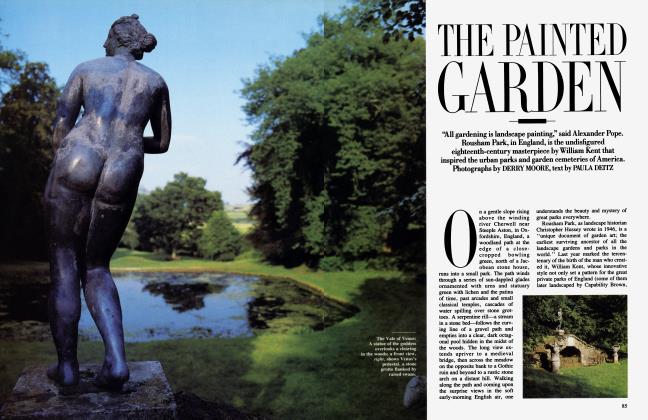

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE SCALPELS OF AREQUIPA

RICHARD SELZER

For the last fifteen years a group of plastic surgeons have journeyed from the land of cosmetic surgery to the “undeveloped” countries of the Caribbean and South America. This year writer and surgeon RICHARD SELZER joined the medical procession with pen and knife

INTERPLAST. It is one of those ugly X names for which Americans with an entrepreneurial need to describe themselves have a penchant. It stands for International Plastic Surgery. Incorporated. The organization—which sends out expeditions of surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, and technicians to perform reconstructive plastic surgery in so-called undeveloped countries— was founded in 1969 by Donald Laub, who twenty-five years ago was one of my interns when I was chief resident in surgery at Yale. In his other life Don practices in Palo Alto, California. Among other things, he has performed what is perhaps the largest number of sex-change operations in the world— over four hundred of them—but now he and I are sitting on a hotel porch in Arequipa, Peru, sipping coca tea.

“Why did you start Interplast?” I ask him, and he tells me that in the beginning it was to get patients for his residents to operate on. As the great majority of cases in the States are private, there is insufficient clinical material for the training of plastic surgeons. A simple solution was to practice abroad. But almost at once, in the face of the need, the overwhelming numbers, and the severity of the various deformities, the priorities were reversed and the needs of the visited rather than the visitors came first.

The length of this expedition will be two weeks. We are a team of twenty.

I am an interloper here. A turkey among peacocks. Just so is a mere generalist among a pride of plastic surgeons. Still, I have been engrafted upon this expedition. My colleagues will be Peruvian doctors and nurses. I shall remove the gallbladders of the Indians here, reset their intestines, ligate and strip their varicose veins—the same work I do every day in New Haven. But I have also come to observe, which is to behold and perceive.

Our trip from North to South America is hardly Xenophon’s march from Babylon to the Bosporus; still, it is in the heroic mold. Twenty people, all unused to and resisting regimentation, each with that certain “sweet arrogance” that belongs to men and women trained to a fare-thee-well in their life’s work—it is not easy. In Miami, a surgeon wanders away and is nearly lost; in Lima, a nurse stops listening and misses a vital connection. Yet in the end we have been coaxed and prodded on and off the succession of planes, buses, and cars that have carried us to Peru. Seventy crates and cartons of equipment have been ushered through customs. Interplast uses none of the precious resources of the host country. We have brought our own: sterile gauze, hemostats, scalpels—all.

We are assembled in the lobby of the W Hotel Crillon, in Lima. The next morning we fly to Arequipa, in the southern highlands. We shall work there in the government provincial hospital named Honorio Delgado. In the evening an exuberance possesses us. It is a kind of glee at the prospect of shared labor and adventure. Friendships which had been initiated in airports along the way are cemented. Absent is the wariness of new acquaintances inching toward intimacy. There is no taking of measure, no hesitation. The team is being forged. A MASH mentality prevails. Veterans of previous expeditions regale novices with tales of surgical derring-do. The initiates sigh and fidget. Later I fall asleep dreaming of Peru. Of condors and gold. Of llamas and emerald mountains. Of cruel Pizarro and his conquistadores.

The flight from Lima to the mountain city of Arequipa takes little more than one hour, but I think the direction must be straight up. Abruptly, Peru vanishes and we are engulfed in fog. Peaks and crags dodge our wings and miss, but barely. The plane flutters, banks, rolls all but over, and we are on the ground. It is less a descent and landing than a careful insertion into Arequipa. Half of us are to be housed in Peruvian homes, the rest are wedged, three to a tiny room, at Turistas, a pink-and-green hotel made of volcanic rock. We do not stop to unpack but rush to the hospital to begin our work. The great clinic, we are told, is already in session, CONSULTORIO CIRUGIA PLASTICA DE INTERPLAST, reads the sign on the wall. Black crayon on yellow paper. Within minutes we are fully engaged in the examination and selection of patients for the days of surgery ahead.

The hospital of Honorio Delgado is slowly, imperceptibly settling into a state of splendid ruination. One day it will be the twentieth century’s medical Machu Picchu. Every floor bears great gouges where tile and stone have crumbled. Every ceiling is a constellation of cracks. Should something break, it will

stay broken. There is no such thing as restoration or replacement. Honorio Delgado has run out of catgut, scrub suits, dressings. Rubber gloves are mended and reused the next day and the day after that. Each scrap of gauze is retrieved from a bucket, washed and folded, and made ready to blot another patient’s blood. The scalpels of Arequipa enjoy longevity. If these knives could speak, they would spin tales of the dozens of incisions each of them has made. At Yale or Stanford, a knife has a lifetime of a single operation. Each procedure here is dictated by the cost of the material needed to do it. The staff is paid, but poorly. Carlos Galdo, the chief of men’s surgery and the equal, at least, of most of the surgeons I have known, earns $300 a month. Before an emergency appendectomy, the patient must buy the suture material, gauze, and knife blade to be used upon him. If there is no money, as is usual, the residents themselves must buy the material, paying for the right to heal their patients. But Interplast, ah Interplast, has come to Peru, its cartons bursting with throwaway knives, suture material of every caliber and variety (catgut, nylon, Vicryl, silk), tanks of anesthetic gas, intravenous fluids, and an array of clever instruments (dermatomes, staples, retractors, endotracheal tubes). We are both proud of and embarrassed by our plenty. Under the awed gazes of our hosts we squirm. Always, we are the rich gringos.

Clinic is held in two tiny examining rooms in which at no time are there fewer than a dozen people. Four examinations are being conducted simultaneously. In one corner Iris Figueroa, a beautiful fourteen-year-old girl, glows among our white coats. Her mother holds up the girl’s right hand for us to see. It has but one finger, the index, which protrudes like a talon. The rest are absent save for a cluster of soft nubbins bunched at the knuckles.

Leo is our hand surgeon. “What is your name?” he asks her.

“Iris,” she says and lowers her gaze.

“Wiggle your thumb,” says Leo. His English is translated into Spanish by a nurse. But what can he mean? There is no thumb. He means only to see if she moves the bone at the base of what should have been her thumb; the one hidden in the featureless pad of tissue in which all five metacarpals exist uselessly. Iris tries to wiggle it; she tries very hard to do what the doctor has asked her to, even shakes her head at the effort. There is no movement to be seen. Still, palpating, Leo feels something at work within that pad of flesh.

“We can separate this ray out,” he says, thinking out loud, “make a web space, deepen it all the way to the wrist. Then she will be able to pinch.” The girl’s mother lifts Iris’s other hand and we see that this one too is blank, blind, dumb. And fingerless. For a moment we are still. Then:

“Is she rightor left-handed?” The interpreter is busy.

“Right,” she says at last. And we smile as though we have just received the best news. And we have. All this while, the girl has been eating our faces with her eyes.

“Put her on the schedule,” says Leo. “I’ll do her tomorrow.”

“There’s no more room on the schedule tomorrow,’’ says Fran Taylor. She has charge of making out the operations list. “In fact, you’re all booked up for the whole two weeks.”

Leo says nothing, only looks down at the small unfinished hand, paw really, that he is holding.

“It’s just the way it is,” says Fran. “We can’t do them all.”

“You tell her, then,” says Leo. There is a short volley of Spanish. Something pale and vague flits from the face of the girl. I think it must be hope. Her head drops down and away. She is trying not to show what is churning inside. But courage has its limits, in Peru as everywhere else, and there are tears. With her single finger she reaches up to wipe them away.

“No room?” Leo asks again. He cannot seem to understand.

“No room,” says Fran.

“Give her a high-priority slip for next year. We’ll be back next year,” he says to Iris. “I’ll fix it then.” Fran writes out a slip of paper, marks it “priority,” and hands it to the mother of the girl.

However, a surgical schedule is not graven in stone. Just when you think you’ve got it made out once and for all time, along come fever, cough, infection—all the mischances of the body— to cause one operation to be canceled at the last minute and another to be put in its place; Lest a precious slot on the list be wasted, substitutes must wait at the ready. There is an understudy kind of chanciness about it. The Indians know this, and they do not leave us until they are certain there is no hope.

Paper is shuffled, the door is let open a bit, and a woman leads a seven-yearold boy into the room. He climbs up on the table that Iris has just left. Where his lip should be, a nude rubbery insect from which a single tooth projects.

“What’s your name?” asks Don.

“Miguel.” Don laughs as though the name itself were funny.

“Say 'el gato,’ Miguel,” he says. “Say ‘Coca-Cola.’ ” The boy looks at his mother. She nods.

"El gato," says Miguel. “CocaCola.” But it is only an approximation. The vowels leak out of his nose; the consonants are blunted, furry.

“Unilateral cleft lip and cleft palate,” says Don. “We ought to get it fixed now. Later, there will be less chance for speech improvement. He’s at the right age.”

“Now,” says Fran, “you know there’s no space for it. Why do you make me say it again and again?” She tells the mother it cannot be done, tells her to bring him back next year. She gives her a slip of paper. They rise to leave.

“Good-bye, Miguelito,” says Don. “Adios, amigo." It is the boy’s turn to smile.

Just at noon the sun comes out for the first time. In its rays the hospital of Honorio Delgado blanches. Through the tiny window of the examining room we see the huge snowy cone of Misti, one of the three volcanoes that ring the city of Arequipa. It is dead, they say. Burnt out. But I don’t know about that. There is just the whiff of temper in that bit of cloud the peak has snagged. What mountain could hold its peace in the face of so much heartbreak? Once, I arrived in Paris some hours later than I had planned, only to find that the hotel had given away my room reservation. "Complet," announced the desk clerk, dismissing me with her back. Very Parisian, I was to learn, after dragging luggage the heft of boulders into a dozen other lobbies in search of shelter, to be met each time with another "complet.” It is a small thing to sit up all night in a foreign city waiting for the dawn. I know that. “No room” in Peru is worse than “complet” in Paris. Still, as I watch the disappointed children leave the clinic, I think of that cold and tired night.

I step out into the waiting room, from which the throng spills to the out-of-doors, where there is a topiary garden—shrubs in the shape of a llama, a condor, an ocelot, an angel, each one carved precisely as if by a surgeon of Interplast. From this garden I spy on the patients. How beautiful they are. Tiny. Even the tallest of them is shorter than the least of us. Every shade of brown and gold is represented in their skin. Their hair is full and black. All their sexuality seems to reside in their hair. Again and again the children are scooped up and pressed into their mothers. The children eye each other’s deformities with solemnity. The mothers, too, cast quick glances. It is said that the Incas were all exterminated during the Spanish conquest, that their race is extinct. But I don’t believe it. The genes of the Incas are here in this courtyard full of serranos. Now and then I see a perfect pre-Columbian face, and then I am sure.

Here, in this legendary waiting room, one would think deformity the* natural state of mankind. No child but with his cleft lip, burn scar, webbed hand. The marred and the scarred far outnumber the others. The children are quiet, reserved. There is no restlessness in them. Only, they wait. The longing in their faces is all for a clever scalpel, a tiny row of meticulously placed sutures that will redeem their lives. See how the examining-room door opens again. Something billows forth from the crowd. Yet no one moves. It is only their breath that has surged. The lucky name is called out: “Fabian Platera Choquehuanca.” A woman carries a fully swathed infant into the examining room. The rest inhale, exhale, and settle into waiting. Many have come on foot from great distances, from villages high in the Andes. Still, they are not disgruntled. Nor are there predatory lawyers circling at the periphery. There is only the eternal eloquence of the wound. All at once, from the examining room, another “no room,” followed by a hush in which I think to hear the volcano rumbling. I go back to duty.

The door bangs open and a young boy of eight runs in and hugs Fran.

They cling to each other, laughing. There is a barrage of Spanish. Fran explains:

“He had a double cleft lip. We fixed it last year.

He and his mother have come all the way from Puno to show us. Look.

You can’t even tell.” She turns to the boy.

“You are handsome,” she says. He laughs and races out of the room.

A nother day. Another ten cleft lips _/l_and palates. We are pushing to get them all done, all that we have promised, before we leave.

A short lesson in embryology: Mesenchyme is that all-purpose undifferentiated tissue of which we are largely composed early in fetal life. Mesenchyme is not stationary, but flows, folding upon itself, rising into ridges, incorporating within itself little sacs and hollows. Within the first trimester of pregnancy it happens, sometimes—far oftener in Peru than in the United States, it seems—that the mesenchyme destined to form the upper jaw, the lip, and the palate fails to fuse in the midline of the face, or even to migrate to the midline of the face. And so there is a cleft where there should have been an uninterrupted smooth and attractive joining. Such an intrauterine mishap runs in families. Should a mother or a sibling have a cleft lip, then the odds turn grimmer for the unborn. Inbreeding, it is said, plays a part, the grouping and concentration of negative influences. And malnutrition. And multiparity in which an eleventh or twelfth child is born to a woman in her forties or later. For the Indians of Peru such risks are high. They live in such a state of genetic vulnerability. Interplast has come here to repair and reconstruct, to correct the inborn errors to which society and culture have made these people susceptible. So we tell ourselves and others. So we believe. But that is not the only reason we have come. Honesty insists that we have each of us come for our own entirely other reasons. The surgical residents have come for the experience of operating on great numbers of these deformities. Within two weeks they will have performed more of these operations than most surgeons will do in a lifetime. For some, it is the opportunity for virtue that we are seeking. Such opportunities are not without the element of self-aggrandizement. For still others it is the exhilaration of the exotic that beckons, or the lovely sense of camaraderie that is to be found in working together for a purpose we think high. Last, there is the need for human beings to challenge themselves. In surgery it is best done by tackling the most difficult of clinical situations and prevailing. Next to the control of the birthrate, the correction of malnutrition, genetic counseling, and the teaching of simple hygiene, all our surgery is nothing. Still, that we have come to do it is enough for us.

A doctor must have a heart that is unmoved by news of a far-off massacre but breaks at the death of Juliet.

In the operating room the ancient X pedagogy of surgery goes on, but here as in Babel. The doctors and nurses of Arequipa speak no English; we, no Spanish. Still, hand guides hand within a sleeping patient. Voices murmur.

“Paciencia, paciencia. Lento, por favor." And after a difficult technique newly mastered, “Felicitaciones, amigo."

As usual, the surgeons are confident, the anesthesiologists nervous. It is the role of the anesthesiologist to rein the surgeon in, restrain, lest in his enthusiasm the surgeon endanger life. These associates are the conscience of the operating room. They, the statesmen. We, the warriors.

¡Miracolo! It is Iris Figueroa who is the patient on the operating table. A last-minute cancellation. An infant with too low a blood count, crackles in his lungs. An anesthesiologist has said no. The infant’s misfortune is Iris’s good luck. Now we are in the middle of the surgery. The skin flaps have been cut. A full-thickness skin graft has been taken from the girl’s groin. There is still much to do.

Anesthetist: “How much longer will you be at it?”

Surgeon: “Another hour and a half or so. Why?”

Anesthetist: “The trouble is...we are almost out of oxygen. The tank is on empty.”

Surgeon: “No.”

Anesthetist: “Yes.”

Surgeon, angrily: “How could you let that happen?” Then, flatly: “We’ll have to find a good place to stop.”

Anesthetist: “That would be right now. I’m going to have to wake her up.”

Surgeon: “Can you wait one minute?”

Anesthetist: “No.”

Just then, the door to the operating room opens and a huge headless tank is rolled, wobbled, carried even, into the room. Two tiny Peruvian nurses are supplying the brawn. They are dwarfed by the giant tank. They use their breasts and their breath to propel it forward. A monkey wrench is found, and the tubing is switched from the dead tank to this new one. A knob is turned. All eyes are on the gauge. No one knows how much, if any, oxygen the tank holds. The needle pops to the halfway mark. It is enough. The surgeon and the anesthetist breathe heavily, as though it were they who had run out of air.

(Continued on page 105)

(Continued from page 59)

Surgeon: “Now can we get on with it?”

Anesthetist: “Trouble is, now there’s no oxygen in the recovery room. This is their tank. The only one.”

Surgeon: “Suture!”

In the central corridor of the operating J. suite, next to a wall, stands a small, gaudy altar, no more than a crucifix on a tablecloth strewn with artificial flowers. No one pays it the slightest attention. But it is there. In the same tiny storeroom that is stuffed with the cartons of our equipment, the men and women of Interplast dress and undress together. We have not the modesty of the Peruvians, who seem shocked by our shamelessness. Here, too, between operations, we chew away at the slabs of tough fried meat and buns that are handed out by a beautiful young woman who is always dressed to the nines for the occasion—flowered silk dress and high heels. What could she possibly be thinking? Now and then someone takes a roll of toilet paper from the table and disappears. Already, for our sins, the diarrhea rages.

¡Emergencia! One of the palates done yesterday is bleeding. A nurse wheels the rattletrap gumey through the doors of the sala de operaciones. The boy, Juan, is eleven years old. A gauze has been stuffed into his mouth. The end protrudes and is draped over his chin. It is blood-soaked, and more blood drips from it onto his bare chest. With one finger, as he has been instructed, he presses the wad against the roof of his mouth. He is utterly calm in his martyrdom. We place him on his side on the operating table. He will be put to sleep in that position, tilted forward even, in order to prevent blood from running into his windpipe. A mask is held over his face. Above it, dark slanted eyes gaze at something far beyond the swirl of doctors, nurses, and equipment in which he is engulfed. Only once does he move, raising one hand to point to the angle of his jaw, where the anesthetist is pressing too tightly.

“Your finger is hurting him,” someone says.

“Sorry,” the anesthetist says to the boy. “How do you say ‘I’m sorry’ in Spanish?”

“Never mind. He speaks only Quechua, anyway. He’s from a village far up. Not even Pizarro got to it.” Only when the boy is asleep and the tube is secure in his airway is he turned on his back. The packing is removed from his mouth. It is chased by a red froth, then pure blood.

“I see it,” says the anesthetist. We peer into the open mouth of the boy, and we, too, see the tom artery at the front of the incision in his palate. Two four-by-four-inch gauze pads have been unfolded and packed in the throat to prevent aspiration. A metal mouth gag is inserted behind the front teeth and screwed open. Now the site of hemorrhage can be seen with ease. Tick, tick, ticking away. With each beat of the pulse another expensive red jet. A single stitch of Vicryl in a figure eight and we are dry. We are safe. The anesthetist holds out his hand, which is completely painted with blood.

“Can someone wash me off?”

A nurse or a doctor, like an artist, must have an illiberal human heart, the kind that is unmoved by news of a faroff massacre, in Cambodia, say, but breaks each time at the death of Juliet. Juan is wheeled to the recovery room, his mouth still stuffed with gauze packing. The lump is in my throat.

The Indians chew coca leaves J. wrapped about a small piece of limestone. The wad is held in the groove between the cheek and the gum. It is the slow activation of the cocaine by the stone and saliva that serves to disconnect, just a bit, the chewer from his hardships. Such usage does not make him happy, nor is it meant to. Only to alleviate. Very sensible, we decide. At the hospital, in the long waiting lines, the eyes of the coca eaters are withdrawn, unfocused. It does seem true that in every culture there is some national elixir to which the people turn for their dreams and for relief. In the spirit of experimentation, shall we say, we pay a little money to a man outside Turistas. Within minutes there are pebbles, there are leaves. In the evening, self-consciously, we try to feel what it is that they feel. Nada. Only, we cannot sleep. And so we go to la peha, the native cabaret. Bottles of pisco on the tables. The nurses and doctors with whom, hours earlier, we have shared disappointment and triumph in the operating rooms teach us to dance. German Munoz, a specialist in the treatment of bums; Luis and Alfredo, who dream of going abroad to finish their surgical training—Luis to the States, Alfredo to Brazil. And the nurses, Juliana, Eliana, and the rest, clapping their hands to the beat, now and then uttering tiny birdlike cries, their eyes gone muzzy with longing. We watch them court each other, the men all gallantry, the women a blend of eagerness and coquetry. Here at la peha it is Interplast that is shy, awkward, encased in a puritan cuirass that holds stiff our hips and shoulders and necks. We marvel at the oiled hinges of our counterparts. At last, midnight, and with it a loss of inhibition. Then we, too, come ashake and aswivel. The music is made with wooden flutes, reed pipes, guitars, and drums. It is immensely erotic, feral. The flutes and pipes cry, shriek, moan. The guitars shuffle chords this way and that. But it is the great drum that governs. Like a cardiac muscle it drives our blood. When, abruptly, the beat changes, we suffer arrhythmia.

"TAonald Laub is assisting a local sur-L'geon, Moises Pacheco, in the repair of a cleft lip. Moises is the single most important man here, for it is he, if anyone, who will inherit the mantle. In a few days Interplast will have departed. Moises will be left to carry on. He is immensely Peruvian—short, beefy, brown, with a wealth of black hair which he has had “styled.” There are gold chains around his neck.

“Tinto,” says Moises to the scrub nurse, and with a sharp stylet dipped in ink he marks out the flaps on the mound of chaotic flesh.

“No, no,” says Don. “Make it longer laterally. Look. Here is the vermilion border. That’s the Cupid’s bow. Yeah, now you’ve got it. jBravisimo/” An hour later, Moises is suturing the two halves of the orbicularis oris muscle, the one used in pouting, sucking, sipping, kissing, all of that. With each suture he restores a new function to that mouth. Minutes later, the flattened nostril rises in a lovely curve to match that of the other side. The defect narrows, is closed. Over the head of the child, the American and Peruvian shake gloved hands.

Later that evening I am walking in JLJ the city with Don.

“Clean, isn’t it?” he says. “No discarded paper or plastic in the streets. No dog shit.” And it is true. Not Paris, but Arequipa is the city of light. If blue skies, herds of mountains, sprays of stars, and clean streets are proof of divine approval, then God surely loves Arequipa. Praise how you will the city that boasts Notre Dame, if to get to the cathedral with unsoiled shoes you have to keep your eyes on the pavement and practice a kind of broken-field running, it just isn’t worth it. In Arequipa the dogs are confined to rooftops and courtyards. In Arequipa in the evening, you can walk and look up at the stars.

O unday. Carlos Galdo has arranged Oan outing for us to a restored eighteenth-century grain mill. After weeks of surgery, clinics, and rounds, we are eager for leisure. We are a caravan of four cars each holding five Interplasticos. There is much hilarity. At El Molino there will be a feast: octopus marinated in lime juice, slices of charcoal-broiled beef heart, pisco, and beer. And dancing, without which a party is not a party in Peru. Peruvians cannot imagine a party where people sit around and converse. What fun is that? they ask. Not much, we admit. The mill is about twenty miles from Arequipa, in the country. I am in the backseat of the last car. Near the halfway mark we cross a narrow bridge that spans a deep gorge at the bottom of which is a swiftly running river. Having crossed, we immediately find that the road ascends sharply, then curves out of sight. The leading cars have already disappeared from view. It is in mid-ascent of that incline that fate casts upon Interplast its most ironic smile. The car stalls. Before the hand brake can be applied, we have rolled backward a few feet and struck a small car filled with people. It is an ancient blue Volkswagen. The driver of that Volkswagen leaps from the car, neglecting, in his ardor for battle, to close the door. Now he and our driver are fully engaged in a passionate discussion which promises to be interminable. I get out of the car to assess the damage. None to our car, I see; only a dent in the front bumper of the other. Never mind, I say. I’ll give him money. Let’s get going. Just then, thinking to disengage us from the Volkswagen, our driver releases the hand brake prior to starting the motor. It is a lapse. We roll back a bit. The hand brake is reapplied. But not before we have once again nudged the Volkswagen. This time, it begins to roll backward down the hill toward the bridge. I chase after it, thinking, I suppose, to reach in and pull up the hand brake. But I cannot catch the car. Faster and faster it rolls. Through the windshield I see the faces of the passengers. Indians, I see. Their eyes are wide with terror. Their mouths are open for shrieking. Just before the bridge, the little blue car takes a small, sickening turn to the left, achieves the rim of the chasm, tips up at the front, and plunges backward into the ravine. All this I watch from a few feet away. And hear the crash far below. For a moment I pause at the edge, then leap. The sides of the gorge are not quite straight. There are stunted shrubs to grab, rocks to brace a foot against. It is an utterly graceless scramble downward, at least half of which is made on skidding buttocks, heels. A series of bounces, really, until that final plummet into the river. A mouthful of raw sewage.

I am twenty feet from the rock ledge where the car has come to rest on its side. From the wreck, whimpering. They are alive! I see three old men. They are covered with blood. The river beneath the ledge is red with it. I try to pull one of the men through a window, but he is wedged. Now I am joined by Bill and Michael. They are both young and strong. I am merely reckless. We shout to each other above the noise of the river. Our voices echo against the walls of the chasm. The air is stagnant, palpable. Michael climbs on top of the car and tries to open the door. It will not open. He pounds it with his fist, a rock. At last it gives, and we pass the three old men from one of us to the next. They are Franciscan monks. They wear long brown habits and rosaries. Somehow, this makes it worse. From the bridge, people throw ponchos in which the injured will be carried up to the road. Other men have come down to help. One of the monks has sustained an avulsion of his forehead and scalp. Blood from the great wound films his face. He is blinded by it. I wipe the wound with my hand, find the artery that is spurting at the base of the gouge, pinch it between thumbnail and fingernail. The bleeding slows, virtually stops. We lay him on a poncho and begin to climb. He is immensely heavy and I must use one hand to pinch the artery. The other is more tired than it has ever been in my life. No mountaineer ever looked more longingly at the summit of Everest than I at the bridge high above. At last we reach the top, and I unpinch my fingers from the blood vessel. The bleeding has stopped. It does not resume. The three wounded men are placed in the back of a truck and taken to Honorio Delgado. The next day we will visit them on rounds. Rows of cotton sutures will crisscross their smiles. From swollen purple mouths they will cast blessings upon us. There will be no single word of reproach. All the same, we will be filled with guilt. We who came to repair and have ended by damaging. Conquistadores!

At last, Carlos and the others have come back to find us. He insists that we go on to El Molino. Shattered, and so malleable, we do. There we find kindly massage, tumblers of pisco. In two hours we are dry. And tipsy. And dancing. Later, on the way back to Arequipa, we stop at the bridge and go to stand again at the edge of the precipice. A rank air hisses up from the depths. Like ones who have emerged from the mouth of hell, we are returned to a state of childhood horror. You are making too much of it, we say to one another. And know that we are making far too little. We pick up stones and toss them over the side. The one I throw takes hours to strike the bottom. It has a muffled sound like the impact of flesh. A noise like that could kill you. I would not go down there again for Saint Francis himself.

A last visit to Honorio Delgado. jfVwhat a far cry it is from my sleek and gleaming hospital in New Haven— all glass and prestressed concrete. And yet, so like. A hospital is only a building until you hear the slate hooves of dreams galloping upon its roof. You listen then and know that here is no mere pile of stone and precisely cut timber but an inner space full of pain and relief. Such a place invites mankind to heroism. For us, Honorio Delgado has become an instrument with which to confront life, a rock that stands firm against the incessant lapping of fate. Even at la pena, at the mill, at the bottom of the ravine, this hospital clung to us like a she-wolf. We could smell her maternal odors penetrating to our hearts. Tomorrow we leave Peru carrying with us the pathetic belief that the way to heal the world is to take it in for repairs. One on one. One at a time. Q

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now