Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

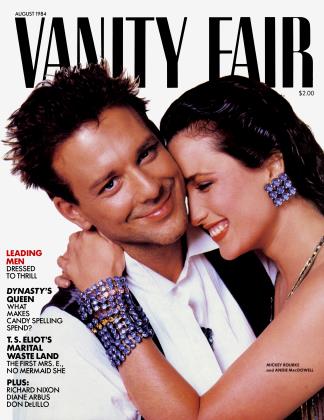

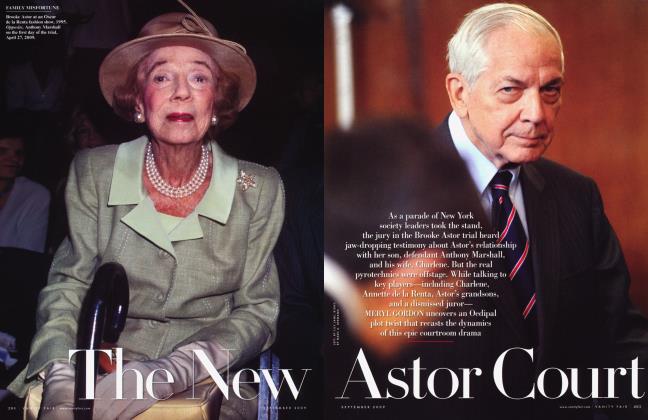

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowVIV AND TOM

What they didn't tell you about T. S. Eliot in Modern Poetry 101 is the harrowing story of his first marriage. It was pure bloody hell. During the Waste Land period, "Tom" and "Viv" Eliot were locked in a neurasthenic drama that pushed him to the brink of madness, and her beyond it. PETER ACKROYD, in & researching his new Eliot biography, penetrated these dark years

PETER ACKROYD

Me was on the telephone to Virginia Woolf in April, talking in what she called his “sepulchral** voice about Viviens swollen legs and their humiliating difficulties with servants.

Thomas Steams Eliot, in his last years, declared that there had been only two periods of his life when he was happy— during his childhood in St. Louis and during his second marriage. The sometimes desperate unhappiness which he experienced in the years between, the years in which he wrote his poetry, can in large part be accounted for by his impulsive but, in the end, unendurable marriage to a young Englishwoman who has been variously described as her husband’s muse and his tormentor. It is possible that she was both.

In August 1914, at the age of twentyfive, Eliot had gone from Harvard to England in order to study at Merton College, Oxford. The following year, which marked the beginning of his career as a poet, was also the year in which his private existence was altered radically; while still at Oxford he met a young woman and, a few weeks later, on June 26, 1915, married her. Her name was Vivien Haigh-Wood (originally Vivienne, but she abbreviated it, although Eliot when exasperated would stretch it out to its original pronunciation). What kind of woman was Vivien when he first encountered her? She was vivacious rather than beautiful, according to the English poet Osbert Sitwell, when he met her three years later. She was self-conscious, alert to the point of oversensitivity. She liked to go to plays and to dance to the music of the phonograph; she always dressed well, although sometimes in a startling manner. She had a gift for expression and an instinctive sharpness of wit which was close to cruelty; her voice was rather high—like that of a parrot, someone said. “Please don’t laugh,” she would say if someone misinterpreted her, “there’s nothing funny about that!” She was described by a member of Eliot’s family as a “delightful person, charming, interested, sensitive to beauty,” and Osbert Sitwell said that she must have seemed to Eliot the embodiment of the carelessness and audacity of youth, although she was, in fact, six months older than her husband.

Her parents, Rose and Charles Haigh-Wood, were an exceedingly respectable upper-middle-class Edwardian couple, representing the kind of Englishness to which Eliot in succeeding years would be most susceptible. Her brother, Maurice, eight years her junior, was an officer in the army. Vivien’s father was a landscape artist and portrait painter, but he derived much of his income from his estates in Anglesey and Dublin. Vivien was, in other words, affluent and socially acceptable.

She was also quite unlike the women Eliot had known at Harvard or at Oxford. In the months before he met her, he had been complaining about both his virginity and his shyness, and also about the lack of female society. He was worried about the future, and did not know what kind of life he wanted after Oxford. Now this virginal, perplexed, intellectually overrefined but emotionally immature young man encountered an adventurous and vivacious young woman. She was for him a revelation of sexual and emotional life, and one in which he might be able to lose all his doubts and anxieties. And what would she in turn have seen in Eliot, apart from a very clever young man who flattered her self-regard by becoming infatuated with her? He was goodlooking and quick-witted, a foreigner who might extricate her from the world of Edwardian respectability, and a poet for whom friends predicted a great future. She complained later that Eliot had “tricked her imagination”; it is more likely that, in the first months of their companionship, he adopted her impulsiveness and gaiety and so seemed much more vivacious than in fact he was. And here were the makings of their unhappy life together: from the beginning, they quite misunderstood each other’s characters.

There were also more immediate problems. During the first months of their marriage Vivien began to suffer from the poor health which was to mark the rest of their life together. Her problems were largely nervous in origin, however, and the symptoms included headaches, cramps, and, from the age of twelve, according to her brother, an irregular and overfrequent menstrual cycle. As a result of the last complaint, she had an obsessive habit of washing her own bed linen, even if she was staying in a hotel.

One of the friends to whom she and her husband turned for advice and support during the early years was Bertrand Russell; he had been Eliot’s tutor at Harvard, and offered the couple the use of his flat in London in the autumn of 1915. He was a notorious philanderer and Vivien herself was somewhat flirtatious, but at first his affection for her was primarily of a paternalistic kind. Indeed, he maintained an almost proprietorial interest in the Eliots’ affairs for the next few years, even after they had found a small flat of their own near Baker Street. Often he would have lunch with Vivien when Eliot was working; he also gave her many expensive gifts. This was to prove a less than ideal arrangement, since on one occasion in the autumn of 1917 Russell broke his selfimposed vow of paternalism and (acceding, perhaps, to her requests) made love to Vivien—at least this is what he claimed in a letter to his mistress, Lady Constance Malleson. The experience, however, he found “hellish and loathsome.” Russell did not explain why, although no doubt Vivien’s physical problems were in part responsible.

It would be wrong to underestimate the bonds between Eliot and Vivien even in the midst of these difficulties. The writer Brigit Patmore knew them both in the early days of the marriage, and has left a remarkable account of their behavior toward each other. They were, by her account, exhausting company because they treated everything with a “terrible seriousness.” On one occasion Vivien told her what a “frightful time” she had with her husband, but Brigit Patmore noticed how Vivien could sometimes enliven him and arouse in him a schoolboyish humor. One has the impression of a couple who relied upon each other, in the sense that they lived off each other’s nerves, and were able to amuse each other also— accomplices against the world.

Nevertheless, the cramped surroundings and sordid environment in which they lived in London threw them too closely together and confirmed the emotional dislocation from which they both suffered; by 1919 Eliot was writing about the “indestructible barriers” which exist between human beings, and proximity gave rise to mutual depression and sickness. It was a form of maladie a deux; when worry and exhaustion made Eliot ill, his condition affected Vivien’s already highly nervous disposition. As a result, they were beginning to spend a great deal of time apart—perhaps they came to an agreement, if only unspoken, that it was best to do so—and they rented a succession of country cottages in which Vivien stayed and to which Eliot traveled from London, where he had become an employee of Lloyds Bank.

Eliot’s reputation both as a poet and as a critic was being established in these first years—a period which culminated in the publication of The Waste Land in 1922. Vivien harbored great ambitions for her husband’s poetry, and there can be little doubt that Eliot, uncertain as he often was, relied upon his wife’s support and encouragement in what seemed to be his unequal battle against unfavorable circumstances. Even when she was away he would send her drafts of his work, and in the margins of a typewritten copy of “A Game of Chess,” in which an anxious, harried woman is portrayed, Vivien wrote “Wonderful.” It has been suggested that such passages offer accounts of Vivien herself, but no nervous, anxious woman who saw herself mirrored in this way would write in such a manner, and it is more likely that Eliot and Vivien were aware of their predicament, and were at this stage inclined to make a game of it. They both possessed a strong theatrical streak, and the element of willed drama in their relationship was not entirely negligible.

Vivien’s nervous illnesses, however, steadily intensified. In the first months of 1923 she had what was described as “catarrh of the intestines” combined with enteritis, and this was followed by a septic influenza which threatened to turn into pneumonia. The main cause of these disorders seems to have been a form of malnutrition induced by the severe diet which her doctors had ordered for her; by the end of April she was reduced practically to a skeleton and had almost died on two or three occasions. Then, on the recommendation of Lady Ottoline Morrell, a friend and patron of many contemporary writers, Eliot sought the help of a German physician who was also a “lay psychologist,” Dr. Marten; he specialized in a treatment which combined near-starvation of the patient with an injection of animal glands, and it appears that in July some cultures were sent over from Germany in order to help Vivien. She was well enough in this month, however, to visit Virginia Woolf, who described her as “very nervous, very spotty, much powdered.” Vivien was certainly acutely aware of her position; in a letter to Virginia Woolf in April she had expressed anxiety about the fact that she had ruined her husband’s holiday in the Sussex cottage which they had rented. Her own sense of isolation was profound; when Eliot returned to London in June, she told Virginia Woolf that she hated the cottage but, although she wished to accompany “Tom,” she knew that she had to stay in comparative retirement. In fact, Eliot was at great pains to be with her as much as possible; he was traveling between London and Sussex throughout the summer of this year, generally on the weekends but also taking one day’s leave each week from the bank.

A very serious problem was his lack of money. In response to one despairing letter, the New York lawyer and patron John Quinn had sent him $400 and promised to do so annually for three years. But his expenses were heavy; apart from the two rents which he was now paying, Vivien’s medical bills were also very large. Despite his attempts at financial prudence he had been living beyond his income, and his savings were quickly being used up. The only way he could earn money was to settle down and write as many reviews as possible for the magazines with which he was associated, but even if the will was there, the energy and concentration were not. The effects of overwork and strain were quite noticeable to Eliot’s friends, and there are many references to the oddity of his behavior. That oddity can be glimpsed, for example, in the manner in which he guarded himself. When Mary Hutchinson, a close friend, was preparing to visit him in some rooms he had taken by the Charing Cross Road, he told her to ask the porter for “Captain Eliot” and then to knock at the door three times. When Osbert and Sacheverell Sitwell were invited to the same place for dinner, they were told simply to ask for “the Captain.” The strangeness of these instructions was compounded by the fact that the Sitwells noticed, while dining with him, that he was wearing face powder, “pale but distinctly green, the colour of forced lily-of-the-valley.” Their observation confirmed what Virginia Woolf thought she had seen— green powder on his face. The year before, she had suspected that he painted his lips, and in March 1922 Clive Bell told Vanessa Bell that Eliot “has taken to powdering his face green—he looks interesting and cadaverous.” Osbert Sitwell’s explanation for this use of makeup was that he wore it in order to accentuate his look of suffering, so that he might more easily provoke sympathy. This would undoubtedly conform with Eliot’s strongly realized sense of drama, contemplating himself as a romantic or dramatic figure, as he once said of Cyrano de Bergerac, and thus enjoying his situation all the more keenly—as if only by displaying his suffering could he actually experience or deal with it. It is significant that the only people who noticed his makeup, and probably the only ones in whose company he wore it, were writers and artists; it is unlikely he powdered his face before going to the bank, for example. His sensitivity to atmosphere was such that he may have wanted to live up to it; wearing face powder made him look more modem, more interesting, a poet rather than a bank official. He was too intelligent not to realize the effect he had on others—that slightly chilling and aloof quality on which his friends often commented—and this was one way of mitigating it.

Since he was living in a state of intense anxiety, such minor eccentricities are quite explicable. A more conventional expression of his strain occurred at a party which he gave in December 1923; he invited, among others, the historian Lytton Strachey and the Woolfs. Vivien, apparently, was not present, and Eliot proceeded to get very drunk; he was eventually sick and then'sank into a stupor from which he was barely able to rise to speak to his departing guests. Throughout his life, in fact, he drank a good deal (rarely showing signs of inebriation—part of his remarkable self-control), and he once confessed to the novelist Elizabeth Bowen that he needed alcohol to get into the mood to write, although this remark may have been more jocular than accurate.

In 1925 Eliot began openly to discuss with his friends the possibility of a separation from Vivien, for her sake as much as for his own. They had been looking once again for a place in the country—anything would do, since they were desperate to get away from London. But once again Vivien’s health broke down, and there seemed no end to her mental and physical agonies. Both Edith Sitwell, the poet, and Ottoline Morrell have described the strange and incoherent letters they received from her, in which she would describe her terrible “troubles” and explain that she did not know what to do. Aldous Huxley has described how her face “was mottled, like ecchymotic spots, and the house smelled like a hospital.” The smell would have been that of ether, which was then used as a tranquilizer for patients suffering from nervous disorders. Vivien would have rubbed it over her body. It has been said that she was an “addict,” but it is rather the case that she was prescribed morphinebased medicines to alleviate some of her symptoms. In the spring and summer of 1926 she was traveling to various sanatoriums in Europe, sometimes with her husband and sometimes alone.

It was during a visit to Rome in this year that Eliot surprised his traveling companions by falling to his knees in front of Michelangelo’s Pieta, one of the first outward signs of his growing attachment to a form of religious belief. On June 29, 1927, Eliot was baptized and received into the Church of England at Finstock Church in the Cotswolds. Vivien was not present at the ceremony. The next day he was driven to the palace of the Bishop of Oxford, Thomas Banks Strong, where he was confirmed in the bishop’s private chapel. This formal attachment to the Anglican communion was extended when, in November, he became a British subject. It was really only the legal recognition of an evident fact: “In the end I thought: here I am, making a living, enjoying my friends here. I don’t like being a squatter. I might as well take the full responsibility.” His dress and demeanor were indeed now of the English type.

Unlike her husband, Vivien was not able to cope successfully with her obsessions and anxieties. In the year of his conversion she was unhappy and often distraught. She was no longer really “normal,” and he had to persuade her in September to return to her sanatorium near Paris.

Throughout this period, in fact, she was going from one sanatorium to another. She was well aware that her behavior was alienating Eliot still further, but she no longer seemed able to control it; it was an instinctive cry for attention and for help. When she returned to London in February 1928 from the Sanatorium de la Malmaison, she began to suffer from the delusion that Eliot was having an affair with Ottoline Morrell. She caused scenes at parties, shrieking at him, “You’re the bloodiest snob I ever knew!” She always knew how to wound and anger him. Novelist Anthony Powell records in his memoirs a rumor about Eliot that was then going around: “They say Eliot is always drunk these days.”

For a man who was peculiarly attentive to manners and to the formal courtesies of “society,” the behavior of a deranged wife would inevitably lead to anxiety and a sense of shame not far

She caused scenes at parties, shrieking at him YouYe the bloodiest snob I ever knew!"

from panic. He often refused invitations to dine; to those who did not know him well, and who invited him and Vivien to social gatherings, he sometimes excused himself on the grounds that he and his wife were too busy to attend evening parties. But he could not disguise the situation from his friends; Virginia Woolf refused to visit them, although her own mental balance was so precarious that her husband might well have forbidden her to have any contact with an apparently “mad” woman. There are photographs which Eliot and his wife took of each other in the garden of their house in 1929. Eliot, seated in a chair with their dog, Polly, on his knees, smiles cautiously at the camera (and at his wife behind it). Vivien stands at the back of the garden, looking elderly and frail and worn.

Early in 1929 Eliot’s face became swollen and two teeth had to be removed—one of a number of dental operations which he was to suffer over the years. His main concern, however, was still with Vivien; he was reading the clinical notes compiled on her in the French sanatorium and consulting with her doctors. He was on the telephone to Virginia Woolf in April, talking in what she called his “sepulchral” voice about Vivien’s swollen legs and their humiliating difficulties with servants. “We’ve been deserted. Nobody has been to see us for weeks.”

When W. H. Auden visited them, he politely told his hosts that he was glad to see them, whereupon Vivien replied, “Well, Tom’s not glad.” The poet Geoffrey Grigson remembered husband and wife, together with their dog, arriving for tea in their Austin-Morris, a sardine can of a car which caused Eliot endless trouble. As Eliot gravely and courteously answered Grigson’s questions, Vivien kept on asking her husband, “Why? Why? Why?” Eliot by all accounts retained a composed demeanor in public, and often launched into laborious and protracted conversations in order to cover up his wife’s nervous interjections, but there is no doubt that Vivien’s behavior humiliated him.

When the American writer Conrad Aiken had dinner with them in the autumn of 1930, he recalled Vivien’s furtive but intense examination of him— “shivering, shuddering’’—and throughout the meal the Eliots directed streams of hatred at each other. When Eliot in the course of conversation declared that there was no such thing as pure intellect, Vivien interrupted with “Why, what do you mean? You know perfectly well that every night you tell me there is such a thing; and what’s more that you have it, and that nobody else has it.” He retorted rather lamely, Aiken thought: “You don’t know what you’re saying.” Vivien was clearly trying to embarrass her husband in front of his friends. This is not a sign of madness, however, merely of desperation. But more disquieting symptoms were seen by Virginia Woolf when they came to tea later in the same year. Vivien smelled of ether, and her conversation exhibited signs of what might broadly be described as paranoia: “Tell me, Mrs. Woolf,” she said, “why do we move so often? Is it an accident? That’s what I want to know.” The Eliots left precipitately when Vivien thought that their host was making secret signs for them to do so.

Part of her anxiety and restlessness may have been due to the fact that she was taking an assorted and not necessarily complementary range of drugs: alcohol-based items for her headaches as well as various morphine derivatives. But the trouble went much deeper than that; her mother’s fear that she might be suffering from “moral insanity” seemed to be justified, and both Eliot and Vivien’s brother, Maurice, believed that she might do something desperate. Maurice has suggested that at some point plans were drawn up to have Vivien committed to a private mental home—the kind of place to which Virginia Woolf had gone during her bouts of madness—but that she “pulled herself together” and nothing came of them. For Eliot now there seemed to be no escape; however often he spent weekends away, and however frequently Vivien visited sanatoriums in England or Europe, her condition was the fundamental fact of his life. And it seems likely that, in turn, Vivien felt that she did not really know her husband at all: “Why? Why?” is the query Geoffrey Grigson remembered, and it sounds as if she were pleading with Eliot to unravel something of his complexity and reveal himself to her. But by degrees the importunity of her behavior made him withdraw from her even more, causing redoubled anger and suspicion. The choice eventually could not be avoided; if he continued to live with his wife, there would be no end to her sufferings and no end to his own. But if he left her, he would be abandoning the one human being who relied upon and needed him. He could not evade the unhappy consequences of either decision. Eliot was a Christian with a profound sense of sin; it is not too much to say that his soul was in peril. He was caught in a trap, and the need for release finally triumphed. The problem remained of how and when to separate, but this dilemma was resolved for him when he was invited to accept the Charles Eliot Norton professorship at Harvard for the academic year 1932-33. The extended period would give him the opportunity both to accustom Vivien to his absence and to break his marital ties with her.

(Continued on page 97)

The Sitwells noticed, while dining with him, that Eliot was wearing face powder, ’'pale but distinctly green, the colour of forced lily-of-the-valleyf

(Continued from page 37)

And so in 1932 the Eliots appeared together as a married couple for the last time. There were the usual visits to friends, such as the Morrells; on one occasion they visited them on Gower Street to meet the Italian novelist Alberto Moravia. There were also familiar trips to the country—to stay with his colleagues from the publishing firm of Faber and Faber, for example. Although Vivien had no idea that her husband was actively planning to leave her, the shock of his decision to go away for such a long time seems to have rendered her even more desperate. She told Ottoline Morrell in July that it was due only to Ottoline’s efforts that she felt able to keep going. When Vivien had visited Edith Sitwell in March, the latter’s maid, who had worked as an attendant in a mental hospital, smelled Vivien’s drugs and told her employer, “If she starts anything, Miss, get her by the wrists, sit on her face, and don’t let her bite you.” Conversation on this occasion was difficult. When another guest offered Vivien a cigarette, she replied that she never accepted anything from strangers; it was too dangerous. And when Edith Sitwell met her by chance on Oxford Street during the summer, she greeted her by name and Vivien replied, “No, no, you don’t know me. You have mistaken me again for that terrible woman who is so like me.... She is always getting me into trouble.” On Thursday, September 15, two days before her husband’s departure, Vivien held a farewell party for him at Clarence Gate Gardens. On Saturday he and Vivien, together with Maurice, drove down to Southampton; he was to sail to Montreal and then travel down to Boston. The Eliots walked on the deck of the ship before its departure, and then she returned alone to Maurice on the shore. When the ship left the harbor, it was taking away her husband forever. It was a decisive moment in Eliot’s life, and one which would continue to torment him.

During his sojourn in America he instructed his solicitors to draw up a deed of separation. His primary aim was to keep Vivien away from him until she had accepted his decision to leave her. His journey home was shrouded in secrecy, and after spending one night in London he traveled down to stay with friends in Surrey. By the second week of July 1933, some three weeks after his return, Vivien must have been informed of the true nature of the situation. In that month a formal meeting between her and her husband was held in the presence of solicitors. “He sat near me and I held his hand, but he never looked at me,” she said afterward. Eliot knew his wife well enough to realize that it would take a great deal of time before she was convinced that he would not change his mind about the separation, and, in her highly anxious state, her paranoiac fears once more came to the surface. She accused both Virginia Woolf and Ottoline Morrell of having affairs with her husband. It was rumored that she was going around looking for both of them with a carving knife in her handbag, but according to her brother she had only a “joke” retractable knife, made of rubber, which she carried for effect. Her behavior was bizarre, but it was that of a desperate rather than a dangerous woman.

Eliot’s decision to leave his wife was justified, and it is significant that no one, not even the members of Vivien’s own family, criticized him for it at the time. The manner of his doing so might leave something to be desired, but when Maurice Haigh-Wood asked if there were any other, less cruel way than that of writing through solicitors, he replied, “What other way can I find?” It is a difficult question to answer.

ivien’s diaries for the years after the Vseparation give an extraordinary picture of a woman who was tearing herself to pieces and scattering those pieces in the sight of all those she had known. At first, as Eliot suspected, she could not bring herself to believe that her husband had in fact left her, and then she feared a plot engineered by the hatred and envy of others. She wrote letters to her husband imploring him to come back and “be protected,” but he never replied to them. And so her overriding aim became to see or waylay him. She went to the first performance of his verse drama The Rock in May 1934, but he did not appear. Her diary entries are filled with pathetic memories of “Tom” as he had once been; page follows page of cramped and troubled handwriting. She was talking to herself because there was nobody else to talk to; she was lonely, muddled, not sure whom to trust or what to do, looking forward helplessly to that moment when her husband would open the door of the flat and return to her.

She discovered that he was going to work at Faber and Faber regularly, and so this was the one place where she thought she might catch him. She had a habit of turning up at the offices unexpectedly and asking for him, but she was always told that he was out or at a committee meeting. His secretary at the time, Bridget O’Donovan, has left her own account of such visits: “I would go down and explain that it was not possible for Mrs. Eliot to see her husband and that he was well. .. she was a slight, pathetic, worried figure, badly dressed and very unhappy, her hands screwing up her handkerchief as she wept.” Vivien must also have guessed that her husband’s absences were not fortuitous. When in March 1935 she arrived and demanded to see him, the receptionist prevaricated with her. Vivien exclaimed: “It is too absurd. I have been frightened away for too long. I am his wife.”

And then, in November 1935, she found him. She had discovered that he was to deliver an address at a Sunday Times book exhibition, and she arrived there with the dog, Polly. This was the confrontation Eliot most feared. She went up to him and said, “Oh, Tom”; he seized her hand and said in a loud voice, “How do you do.” The dog recognized him and jumped up at him, but he seemed not to notice. When he spoke at the exhibition, Vivien stood the whole time, keeping her eyes fixed upon his face. After he had finished, she went up to him and said, “Will you come back with me?” He replied: “I cannot talk to you now.” She gave him three of his books; he signed them and returned them to her. Then he walked away. They were never to see each other again. In the following month Vivien sent out Christmas cards signed “From Mr. and Mrs. T. S. Eliot.”

Eliot’s reactions to this meeting are not known, although it must have profoundly embarrassed and unnerved him, not least because further public encounters of that kind were always possible. His fears were no doubt compounded by the fact that Vivien’s behavior was becoming more and more erratic. As if to lure her husband into a false sense of security, she pretended in the following year that she had gone to America and had hired a secretary, called Daisy Miller, to answer her correspondence in her absence; but she herself was Daisy Miller. In the spring and summer of 1936, she went to the Mercury Theatre on at least seven occasions to see his play Murder in the Cathedral. And then she disappeared from sight; the diary entries stopped.

By August 1938 she had been committed to Northumberland House, a private mental hospital in North London. The records of that hospital have been long since destroyed, but Vivien’s brother has explained what happened to her. Her physician, Dr. Miller, seems to have instigated the move in the summer of 1938 since it was his belief that “she was in need of professional care.” Since Eliot was the one most involved with Vivien’s welfare, he must have either approved of or acquiesced in the committal. He was also a trustee of the Haigh-Wood estate, and was responsible with Maurice for Vivien’s financial affairs; they must, for example, have paid her bills at Northumberland House.

Maurice reported to Eliot that she seemed “fairly cheerful” in the mental hospital. But the long-term effect on Vivien must have been profound; already a lonely woman, she had been dispatched into an asylum by people whom she knew and trusted. The paranoia which is evinced in the diaries of her last years at Clarence Gate Gardens is then partly justified if she suspected that such a course might be taken against her. There are reports that she attempted to leave Northumberland House; it seems that she stayed on one occasion with Louise Purdon, a “night-nurse” with her own flat above a chemist’s, until she was found and taken back. But these reports cannot now be substantiated; we are left with the bare fact that she spent the rest of her life in confinement.

In his 1939 play, The Family Reunion, Eliot created a hero who is pursued by Furies. Some critics have suggested that Harry’s guilt at apparently murdering his wife is a reflection of Eliot’s own feelings after separating from Vivien. The play was in fact being written during the period which led to her committal in Northumberland House. “You would never imagine anyone could sink so quickly” is Harry’s comment on the death by drowning of his wife. And the description of her—“a restless shivering painted shadow”—is very close to contemporary accounts of Vivien.

On January 22, 1947, Vivien Eliot died quite unexpectedly in Northumberland House. She was fifty-eight. On her death certificate the causes were listed as syncope and cardiovascular degeneration. She had worn herself to death. It was so sudden that even her doctors were taken by surprise, and to her husband the news came as a profound shock. She had died during the night, and it seems that Maurice Haigh-Wood telephoned Carlyle Mansions, Eliot’s home after the war, very early in the morning; Eliot’s friend John Hayward received the call and then passed on the news to Eliot, who, according to another friend, “buried his face in his hands, crying, ‘Oh, God! Oh, God!’ ”

Vivien Eliot was buried in a cemetery in Pinner, Middlesex; her husband and her brother were among the few mourners. Her life had been full of pain and perplexity; it is not too much to say that her emotional needs had been fastened on a man whom she never properly understood, and that he in turn was baffled and then enraged by her insistent and neurotic demands upon him. And so it was that she died alone in a mental hospital; as Eliot told Violet Schiff, one of the few who had known them both from their earliest days together, death could only have been a deliverance for her.

Eliot was to live for another eighteen years. One friend has said that he could never bear to mention Vivien’s name, and another has written of his feelings of “guilt and horror, which haunted him daily,” and how once he observed, “I can never forget anything.” The next few years were ones of unhappiness and illness, as if Eliot felt that he must serve a period of penance after the death of his wife. And it was only in the warmth and serenity of his second marriage, to Valerie Fletcher, his secretary, whom he wed in 1957, that he was able to dispel that “shivering, shuddering” ghost who had haunted him so long.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now