Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTeen Dreams

Stephen Schiff

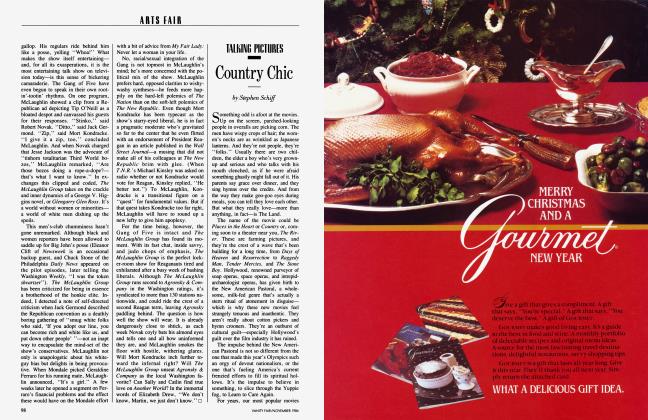

TALKING PICTURE

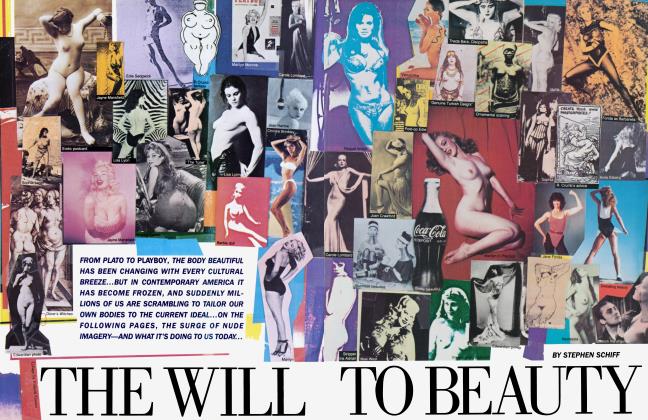

Teenage boys, who are the chief consumers of American entertainment, are unhappy creatures. Passing the hours in a thick haze of hormones, awkwardness, and benzoyl peroxide, they want out—and they don't want to work very hard getting there. And that is why, in almost every medium, they go for pornography. By pornography, I don't mean just erotic no-no's—Penthouse Pets and Debbie Does Dallas. I mean the cultural equivalent of a narcotic: the shortest, most reliable path to escape, orgasm, obliteration. In music, for instance, teenage boys like heavy metal. In cuisine, hamburgers. In literature, comic books. (In higher literature, Stephen King.) In art, Christie Brinkley posters. And in movies— well, that's what I wanted to talk to you about.

During the late seventies, two forms of movie pornography were manufactured just for adolescents. The one that drove right-thinking moms crazy was the psycho picture, which was widely misinterpreted as being antisex. It was always about a faceless fiend who would peep at lovemaking teenagers and then, in a puritanical snit, murder them. But Halloween, Friday the 13th, and their kin weren't endorsements of their maniacs' higher moral standards; these movies had subtler motives. When kids watched the sex, they naturally became aroused; then, when the madman's knife plunged, they shrieked, leapt into the air, had giggle fits. Tension and release. Unless a teenager was willing to don an oversize raincoat and skulk away to the Pussycat Art Cinema, this was the closest to orgasm he could get in a darkened theater.

Then there was the party movie, whose ancestry dates back to such farseeing pioneers as Annette Funicello and Frankie Avalon but whose more immediate roots can be traced to Animal House. These were pictures about outcasts, maladroit boys preyed upon by the secure and the powerful (in short, the jocks). In the party movie, the tension came from the nerdy heroes' pursuit of vindication, and the climax was always an orgy: revenge, spectacular destruction, ecstatically spurting beer cans.

Finally, in 1981, an unsung visionary named Alan Myerson realized that the screen's morals had loosened enough to admit the next step in teen fodder: actual blue movies, with sex and nudity and all the yummies grown-ups trundle off to Times Square for. Thus was born a cheap little picture called Private Lessons, in which a whiny youngster lost his virginity to his daddy's sultry maid, played by that precipitously aging love goddess Sylvia Kristel. The movie was coy and simpleminded, and the sex in it mostly teasing flashes. But it worked. Private Lessons was a bigger box-office hit than Nashville, than Norma Rae, than Chinatown. And after it, the deluge: The Last American Virgin, My Tutor, Homework, Spring Break, Private School, Up the Creek, Meatballs Part II, Porky's, Porky's II, Police Academy, Revenge of the Nerds, and the art film of the cycle, Risky Business. As the psycho movie faded (overkill?), the party movie expanded to include the fruits of Myerson's scholarship. Now the outcast boys were virgins. Their dream women were the property of the jocks. And victory meant not only reprisal but sexual initiation at the experienced hands of the prettiest girl around, who combined towering piles of erotic symbolism—she was Madonna, whore, mother, sister. Above all, she was cheerleader.

These movies wouldn't bother me so much except that, with stuff like Porky's raking in the profits, no one in America wants to make serious pictures about teenage sexuality. In fact, I didn't know what we'd been missing until I saw the astonishing French film A Nos Amours, which is being shown at this year's New York Film Festival. Directed by Maurice Pialat, it's a harsh, rough-edged movie about a young girl, Suzanne (the plain but mysteriously sensual Sandrine Bonnaire), who loses her virginity and then, in the face of a tom family life, be gins to take sex like a drug, frequently and dependently, and always to deflect love, never to enhance it.

For her, sex itself functions as a kind of pornography. A Nos Amours isn't comforting; it's a personal, angry, even vengeful movie, full of unsettling intimations of incest and cruelty. And it feels lived. Pialat himself gives a perverse and bruising performance as the father, and the scenes of berserk family squabbling are so wrenching, so detailed and true, that they seem to bleed off the screen into the world around them. Yet for all its turmoil and fury, A Nos Amours has a haunting, elegiac quality: Pialat notices striations of light on a tile floor, the pleasure Suzanne's brother takes in the smell of her skin, the buggy anguish of Suzanne's mother, who looks mortally love-starved—she's withering and dying before our eyes (and her eerie, mirthless smile will be the last thing to vanish). After dozens of American teeny-porn movies, it's hard to imagine a masterpiece about adolescents and sex, one that expands the universe of teenage concerns instead of reducing it. But that's what Pialat has given us; certainly A Nos Amours is the best movie I've seen in 1984. One wonders whether it could ever have been made in a country where teenagers are regarded only as a market, never as a subject.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now