Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowVISUAL ART

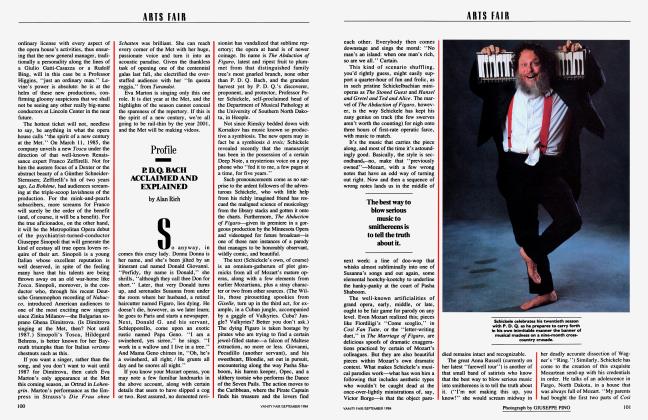

ARTS FAIR

Pleasures Fat and Lean

Cristina Monet

Concurrent exhibitions of ToulouseLautrec at the Museum of Modem Art in New York and of Renoir at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston only reinforce one's prejudices. This redoubtable pair have little in common but that they have been domesticated and overexposed to the point of invisibility.

Renoir's bourgeois pastorals, his sugarplum children and uberous women have been reproduced ad nauseam for the embellishment of servants' quarters and doctors' waiting rooms. Lautrec's graphics have been wantonly pre-empted for everything from spicing up the rumpus room to cocktail napkins and department-store shopping bags.

Perhaps the reason both have achieved, if not been blighted by, such questionable popularity is that at their most accessible they seem to offer an illusion of escape (one idyllic, the other devil-may-care) from the humdrum of daily life. Where Renoir creates images of bucolic and blameless delight—only as erotic as a mother's breast, only as seductive as a baby's behind—Lautrec, like a Fellini-esque ringmaster, regales with a glittery grab bag of existence: dancers and whoremongers, rowdy observers, tarts, and dandified, decadent johns.

The bourgeoisie, with its piss-elegant manners, its predictable posing and acquisitive concerns, is alien to Lautrec. In Renoir, its weight and fat stability are implicitly approved. The scion of an ancient, noble house, Lautrec is at home in his fin de siecle underworld, illuminating with neither passion nor prejudice its ironic paradoxes, its frenzied gaiety, and its morning-after torpor. The slumped postures of the prostitutes in Au Salon de la Rue des Moulins suggest that the wages of sin are paid in abject boredom. The thoughtful melancholy in the face of Moulin Rouge dancer Jane Avril even while she is blithely kicking up her skirts (in Jane Avril Dansant) attests to the painter's oblique empathy.

Vicomte Henri-Marie-Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa was still afloat in his mother's womb when Renoir was exhibiting in the official Salon of 1864. By 1880, when Lautrec had had the accidents which—due to his inbred lineage—were to dwarf him forever, Renoir had secured universal renown with such sumptuous portraits as his Portraits de Madame Charpentier et Ses Enfants and such scenes of sun-dappled haute bourgeoise conviviality as Bal du Moulin de la Galette.

A tailor's son, apprenticed at thirteen as a porcelain painter and a decorator of fans, Renoir never ceased to be awed by the fullness of life—or by his own gift, to him the most wondrous of all life's bounty. At home with his senses, he distrusted intellectual formulations and wished only to share his delight in the fecund world—lush fruit and flowers, cherubic children, and fat, domesticated women.

Standing amid an embarrassment of Renoirs a century later, one is apt to be surfeited by flesh and stifled by sentimentality. It is not the fatness but the fatuousness that repels. "You've got to have a feeling for tits and ass," he is said to have said. Granted. But shouldn't there be something between the ears?

Except for the late period—when Renoir's lifelong quest for an authentic cultural past led him to abandon his submissively bovine womenfolk for a mythic landscape of brutal, archetypal Earth Mothers—his is an exultation one finds it hard to share.

At seventeen, Lautrec arrived in Paris with his past in his pocket, with his aristocratic heritage and the physical grotesqueness it had visited upon him. Forever barred from the pastimes of his patrimony, he cultivated instead his deft hand and mordant eye, drawing the Thoroughbreds he could never gallop, the hunt he could never join. His hunting ground became the Paris underworld, where the crowds surged and danced—where nothing was still.

Surpassing the celebrated eccentricities of his father, Comte Alphonse (who'd been known to drive through the Bois de Boulogne in a coat of mail and dismount to milk his mare when thirsty), Lautrec made high style of his deformity. He flaunted it flamboyantly and handled it with scorn. He enjoyed going about Paris with his cousin Gabriel Tapie de Celeyran, whose extraordinary height gave Lautrec's own lowly measure even more dramatic scale. When Yvette Guilbert, on seeing one of his caricatures of her, protested, "Really, Henri, you're a genius at distortion!" he suavely replied, "But naturally."

Whoring and drunken, princely and profound, Lautrec celebrated the beauty of the dispossessed, the pretenders at life, the humiliated and brave. At a time when Renoir's sugar-and-spice-and-everything-nice is no longer palatable to the sentient few, a bracing dose of Lautrec's uncompromising vision is salutary. His images are of the underside of the fin de siecle, that twenty years or so in which the whole concept of urban ennui came to consciousness. Whether behind the green glow of absinthe and the pop of champagne corks or behind the scraping of coke spoons in tawdry night spots, the nameless anxiety is ever the same. It seems fitting, as our own century screeches to a halt, to pay homage to Lautrec, the first great portrayer of the dance on the precipice.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now