Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBRUSHING UP

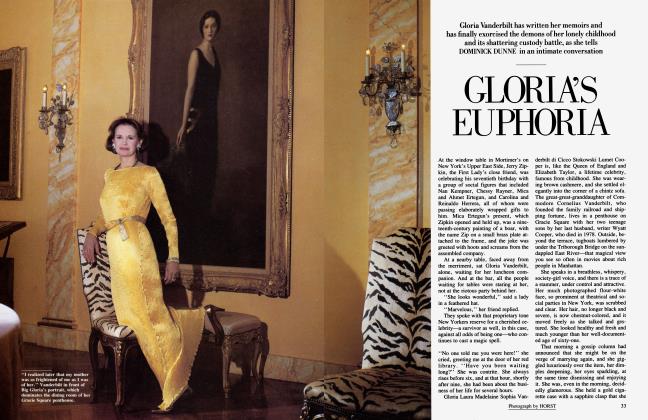

Jennifer Bartlett is one of the most talented painters of the generation between Rauschenberg and the graffiti babies. She wears good clothes, commutes to and from Paris on the Concorde, and has a major retrospective of her work opening this month. JOAN JULIET BUCK caught up with her

During the 1970s Jennifer Bartlett spent a great deal of time writing a novel. This was, she says, because she couldn't say enough with paint. Her writing was "an attempt to categorize, catalogue, and classify events," and she titled the manuscript, in a straightforward sort of way, "History of the Universe." It grew to around two thousand pages of journal entries, character sketches, passages written in verse, and autobiographical narrative, the bulk of which has been distilled into a two-hundred-odd-page book that will appear later this year. Her publisher describes it as a roman a clef.

Bartlett's approach to her novel— breaking down information, speculating, categorizing—is similar to her method as a painter. The show in 1976 that made her a star (the show that New York Times critic John Russell called "the most ambitious single work of new art that has come my way since I started to live in New York'') consisted of 988 separate paintings on baked-enamel squares. The shapes, colors, and lines on the squares were repeated and manipulated throughout the work so that, as Russell remarked, "by the time that we have pondered the 54 different blues which have gone in to the final 'Ocean' section we shall have enlarged our notions of time, and of memory, and of change, and of painting itself."

The series of exhibitions at the Paula Cooper gallery that followed "Rhapsody," the 1976 show, proved that Jennifer Bartlett was consistent. She had an ability to concentrate on one subject and from it produce pieces that could, as Grace Glueck pointed out, also in the Times, be "thought of in musical terms... the statement, development, restatement, variation, and elaboration of a number of themes." In 1981 she showed watercolors and drawings made during a rainy winter in a house in Nice for which she had exchanged her loft in New York with the English novelist Piers Paul Read and his wife. She had had nothing to do but stare at a small garden where a cherub pissed into a small pool between cypress trees, and the cherub, pool, and trees became the subjects of her work. In the Garden was published as a picture book, and in 1983 the garden appeared in a series of huge oil paintings. By then her work was being compared to film because of the way she chose to angle her point of view. Now, inspired by the three-dimensional forms— chairs, a table, a house—she built as part of a commission for Volvo, she is working on sculptures: boats and houses built by her assistants to be the subjects of her paintings. They will also be shown as separate works. So far she has touched every art but ballet.

When I visited the Reads five years ago, while Jennifer Bartlett was in their house in Nice and they were in her New York loft, I was struck by the sight of shelves of extremely fat files labeled "History of the Universe," and, more prosaically, "Letters," "Diaries." These faced the elevator door, and farther on, shelves were stacked with paints, pastels, knives, and brushes in great quantity. In the studio were dozens of panels covered with brushstrokes, destructured images in pale blues. My God, I thought, this woman never stops.

A few months later, at a Sunday lunch, Jennifer Bartlett turned out to be an ironic, self-deprecating, elegant woman with short black hair and a slight drawl. She wore bright-red lipstick, eye makeup, good clothes. The presence seemed difficult to reconcile with the traces of furious output I had seen in her studio.

Jennifer Bartlett was bom Jennifer Losch in Long Beach, California. "Our famous ancestors are Cardinal Wolsey and Tilly Losch, the dancer," she says. Her father was a pipeline contractor, her mother a fashion illustrator. "We lived in an idyllic spot right on the ocean with just a twisted boardwalk in front of the house and then sand. You could watch whales going by on their way to mate. . .

"I wasn't the most popular person in school, though I was in a popular group. I found this discouraging, so I read a lot, which I guess was a way of isolating myself. My grades were bad whenever I was insecure or someone insulted me. I'd just walk out. I started that in kindergarten. I'd hide in the bushes all night, leaving little notes on toilet paper, ringing the doorbell to say, 'Don't try and find me.' Once, when I was about ten, I called up and made a reservation to go to New York. I was astonished at the price of the ticket.

"In the sixth grade I became a deeply dedicated explorative atheist. I would go to all the different churches in the neighborhood and argue with the Sunday-school teachers about their religions. I was always sort of angry...I know I'm describing a complete pain in the ass."

Mills, a California liberal-arts college for women, was the only place she applied to. "I thought people who went back east to school talked East Coast, which I found revolting stylistically." She was encouraged by her art teachers at Mills, although her work was not conventional. "I'd do these very large undersea pictures with everything that's under the sea in them. In fact, I've just recently completed another one." The smile widens—she loves describing absurdities, obsessions. "Spanishmission scenes were my favorite. In the foreground the Indians work in the fields, then you have them cooking their meals right behind, then you have the mission, with the nuns and the fathers, and behind that you have some cows and stuff, and behind that you have the cliffs where they throw over the goods to the ships that are waiting, and then you have the ocean, and then you have.. .Europe!" The missions, of course, were on the West Coast.

Mills was a special college. Intimate, stimulating. Darius Milhaud and John Cage had been in the music department; the graduate assistant was Steve Reich. By her junior year, Jennifer Losch was working in the graduate department of painting. "That's when I met Elizabeth Murray, who really is my oldest friend. She was incredibly sophisticated—sitting on the floor, reading Joyce and laughing. She painted all the time, just painted. I looked at her and I knew what I was supposed to be doing: there wasn't any question of waiting for inspiration, you just paint, but paint all the time. I was infatuated with Arshile Gorky and de Kooning then, but I can remember my two favorite painters were Cezanne and Raoul Dufy, which is hard to reconcile with my interest in a good formalist tradition.

'Now I have an idea about efficiency and survival."

"My relationship to education was strange. I don't like to learn in front of people. I've always been insecure about learning, so I managed throughout my career to not try things I didn't think I'd be good at, and I'd invent another project and do that instead, but thoroughly."

She became Mrs. Ed Bartlett when she was twenty-two, and the couple went to Yale—he to medical school, and she to the art school. "The only part of my life that has been without complications in terms of making decisions is my professional life." She finished the three-year graduate course in two years, taught in Connecticut, lived in the country with her husband, and took a SoHo loft for $175 a month. She was driving, teaching, painting, and cooking. "It was a nightmare. It was shortly after that that we split up.

"The seventies are a bit of a blur for me. I was writing 'History of the Universe,' telling all of these stories about myself, and after I wrote it I had nothing to say anymore. It seemed alien to me. I was involved with painting, but I was never really satisfied. Some painters have total confidence when they're very young. I was not terrifically fond of my work, but I was real stubborn. It was an extremely competitive, macho kind of situation then. The conceptual artists didn't think I was a conceptual artist, and the painters didn't think I was a painter. Everybody was intense and passionate, totally poor and having the electricity and the telephone cut off once a month. Even so, I would n^ver take the subway, I always took taxis."

She had been surviving on $6,000 a year until the "Rhapsody" show, when she made more money than she had ever seen. She kept teaching because she didn't trust her success, and then bought the loft in New York where she now lives. "One night during that time I had dinner with Paula Cooper and another artist. The artist and I were both talking about ourselves nonstop—the torture and trouble we went through, blah-blah-blah—and criticizing everyone else. Paula drove me home and said, 'I never want to go out socially with you again until you stop talking about yourself. It's such a bore.' She's much that way, and those of us who are in the gallery are lucky to have her as a dealer. She communicates what she likes or doesn't like about a body of work, and it has nothing to do with whether it sells or who else likes it or what. It's always absolutely her. So that when she encourages something, you trust her."

Continued on page 107

Continued from page 84

Jennifer Bartlett keeps away from Paula Cooper's gallery, however. "I knew that, since I got upset when I read about other artists in art magazines or hung around Paula's gallery, I had to stop. And I stopped hearing a lot of stuff that wasn't my business. Now I have an idea about efficiency and survival. The older I get, the less I like to talk about my work." She feels powerless against criticism: "You can usually sense when people don't like your work, and there's not much you can do about it. It seems to me that I spent my childhood convincing people that I wasn't a bad person, and the thought of having to spend another forty years trying to convince people I'm not a bad artist is just too horrifying." This is from a woman who wins awards (most recently from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, in 1983) and has one-woman shows around the world. The book accompanying her retrospective at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis this month is a lavish volume published by the Abbeville Press.

Bartlett also lives in Paris, where an apartment in a famous Henri Sauvage 1912 white-tile building has been turned into a bourgeois version of a loft. Alvar Aalto furniture "chosen in a day and a half' ' in Finland fills a tall white room that remains spare and cool. She travels by Concorde, a little less now that she is married to Mathieu Carriere, the German actor she kept visiting in Paris. Carriere, "who's been a movie star since he played Tonio Kroger at thirteen," is a tall, thin, blond man eight years her junior. He likes to play chess against himself and recently published, in German, a study on Kleist. He is extremely handsome and gives her excellent jewelry at Christmas. They met five years ago when a mutual friend insisted she come to dinner. "This strange man detached himself from the others and started making salmon sandwiches for me, and we've been together ever since."

The new pieces she is working on, the boats made of ready-to-rust steel, the houses five feet tall, and the long fences, demand a larger organization than she has had so far: "I've hired four assistants for the first time. I want to get rid of the furniture in New York, since we have furniture in Paris and here the whole place can be filled with the things. Mathieu has the office, but his territory is really the bedroom because he's very devoted to television. He likes it when I work; he'd hate it if I didn't. At the time I met Mathieu I was already sort of established, so he met me knowing who I am, and was interested in me probably in part because of that. It was a very different situation than having a high-school sweetheart whom you're in deadlock competition with 90 percent of the time."

One of the criticisms that Jennifer Bartlett resents is the line uttered by a former friend: "Jennifer is a legend in her own mind." The quip underestimates the power of her positive thinking. The task she set herself in painting is now realized in her life: the reconciling of paradoxes, the squaring of the circle, being earnest while having fun, setting up restrictions and playing within them. In Paris she rarely leaves the apartment, and apples grow on the balcony. Movie stars come to visit while Jennifer works in the studio, a housekeeper cooks dinner while Jennifer apologizes in California French for the burgeoning numbers at table. There is no actress glamorous enough to play Jennifer Bartlett. She believes in hot lunches, good clothes, and champagne. And she never stops working.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now