Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE LAST DAYS OF SAIGON

JAMES FENTON

who was there

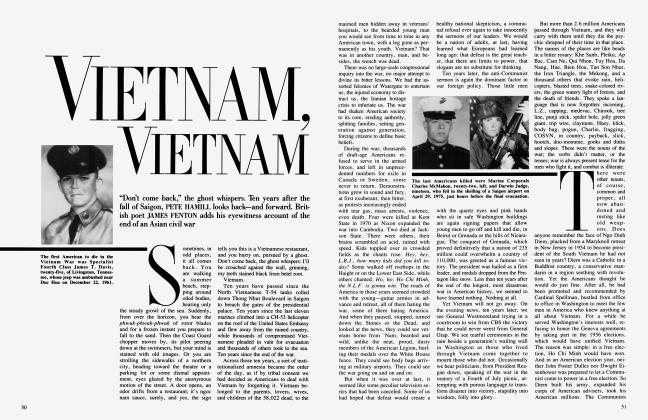

I arrived in Saigon from Bangkok on April 24, 1975, the day before my twenty-sixth birthday, determined to stay and watch the city fall. That evening the garden of the Continental Hotel was crowded for dinner. The famous Dr. Hunter S. Thompson was there, surrounded by admirers. All the Indochina hands were back, so it seemed, for the last act—which, to the Americans, meant the evacuation. My superiors on the Washington Post were gloomy, having been ordered to leave with the American Embassy, on pain of dismissal. Being British,

I was perhaps immune from a sense of impending cataclysm. Everyone was talking about the secret password, which would be broadcast when the time came to go: an announcement that the temperature was 105 and rising, followed by the song "I'm Dreaming of a White Christmas."

While the Americans were removing their friends and their friends' friends from Saigon, at a rate of 10,000 a day, the Vietcong were investing the place with their own troops. The operation was haphazard. The soldiers came in wearing Saigon uniforms, in military trucks that had been acquired during the last few months, as the southern army had retreated in disarray. They took up positions near important installations, in order to take control swiftly when the time came.

On the afternoon of April 28 I thought. That's it, the insurrection has begun. I was in my room at the time, when without warning the whole city became ablaze with rifle fire. I went up to the top floor of my hotel, where a deserted billiard room was a relic of the days of American R. and R. But there was nothing to see, only a noise—a massive, unvaried, unstinting noise. Then, as suddenly as it had started, the firing ceased. The opinion in the hotel was that Marshal Ky was back.

I walked out into the deserted street. No dead bodies. Nobody much around. The timing had been brilliant. Minh had finished his speech calling on the Americans to leave, and on the other side to negotiate. The other side had announced at once that this was not enough, there had to be unconditional surrender. From now on, we thought, anything could happen, and happen very swiftly. We were already at the mercy of the Vietcong and the North Vietnamese.

At the Continental Hotel the next morning, all the talk was about the previous night's fighting. People had seen planes shot down with Strela missiles, and several who had seen this were convinced now that they should leave. I remembered my resolution: whatever happens, stay.

Some people get rich on others' misfortunes, and it appeared that I was one of them. I became, during the course of the day, the acting bureau chief of the Washington Post. I had a bureau.

The keys were waiting for me, together with a charming farewell note from the staff. I had a pleasant young Vietnamese assistant, who was good enough to show me how to get at the petty-cash drawer. There was a nice bathroom, also plenty of books and a bottle of Polish vodka in the icebox. I settled down to work.

David Greenway, then a correspondent for the Post, phoned me from the embassy. They were stuck. Nobody had come for them, and the embassy staff were getting nervous that the place might be shelled. Oh, and did I want the car keys? They had left the Volkswagen by the embassy gate.

Now the helicopters, the jolly green giants, began to appear, and as they did so the city suffered a terrible change. The noise of the machines as they corkscrewed out of the sky was a fearful incentive to panic. And as the evening grew darker it seemed as if the helicopters themselves were blotting out the light.

Returning to my new office that evening, I found a note from my nice Vietnamese assistant informing me that the office was likely to be looted by soldiers and that he had therefore taken home the petty cash. This was the last time I heard from the man. Then I went to the icebox and broached the Polish vodka. It turned out to be water.

As we gathered in the Caravelle Hotel a few hours later, the press corps were in the best of spirits. We did not know how slow or bloody a takeover to expect, but this did not spoil the brave mood of the evening. We had a distant view, from the penthouse restaurant, of the war. Toward the airport an ammunition dump was exploding. Great flames would rise up and slowly subside. It was like some hellish furnace from Hieronymus Bosch.

The next day, April 30, Saigon fell, faster than we could have believed possible. It was the strangest and, I have to say, the most exciting day of my life.

At the American Embassy the looting had just begun, and the streets outside were littered with typewriters. Several cars had been ripped apart. I went into the embassy with the looters. Paper, files, brochures, and reports were strewn around. Because I was regarded suspiciously I began looting, in order to show that I was entering into the spirit ofthe thing.

On the first floor, a framed quotation from Lawrence of Arabia read: ' 'Better to let them do it imperfectly than to do it perfectly yourself, for it is their country, their war, and your time is short."

I turned into a small kitchen, where a group of old crones were helping themselves to jars of powdered milk. They looked up and saw me, screamed as if found out, dropped the powdered milk, and ran.

I did not realize at the time that there were still some marines on the roof. As I forced my way out of the building, clutching my pile of looted books, they threw down tear-gas grenades onto the crowd. I found myself running hard, in floods of tears.

When the sirens wailed three times, it meant that the city itself was under attack. I returned to the hotel roof to see what was happening. Across the river, you could see artillery firing and the battle lines coming closer. Then two flares went up, one red, one white. Somebody said that the white flare was for surrender. In the restaurant the waiters sat by the radio. I asked them what was happening. ' 'The war is finished. ' '

I looked down into the square. Almost at once, a waiter emerged from the Continental and began to hoist the French flag. From the battlefield across the river, the white flares began to go up in great numbers. "Big" Minh's surrender broadcast had been heard.

I could not have guessed that, in the space of a mere morning, the last Americans would leave (at 7:53), and that the South would surrender.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now