Sign In to Your Account

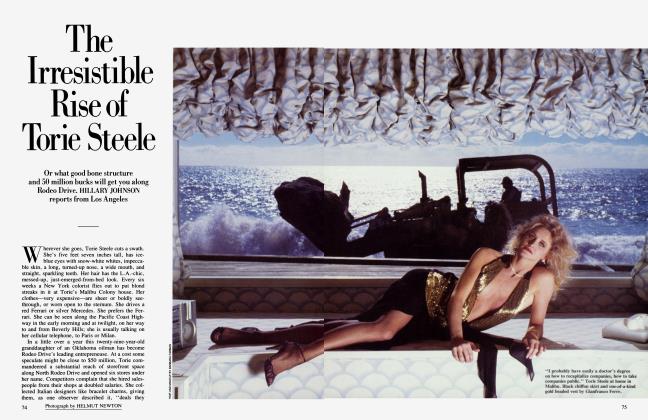

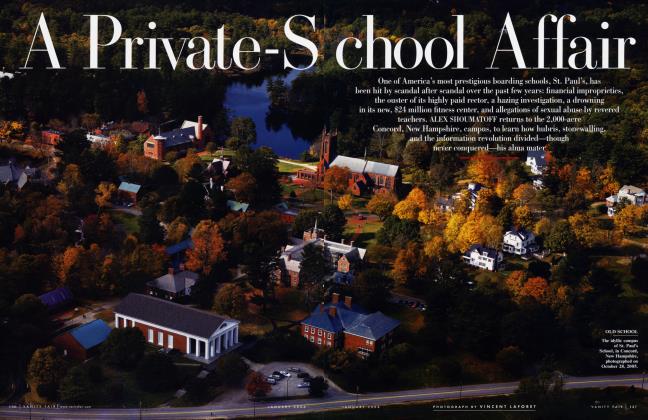

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLOUIS AND CANDY

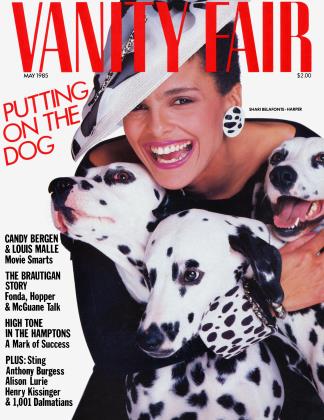

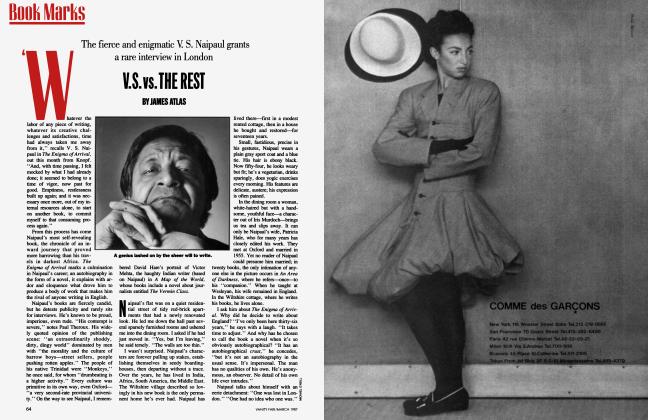

His new film, Alamo Bay, is now in the theaters, and director Louis Malle is in Paris with wife Candice Bergen for a few months' vacances. JAMES ATLAS followed him there to hear him talk about film, family, and his fascination with America

JAMES ATLAS

Louis Malle and his wife, the actress Candice Bergen, were planning to leave for Malle's country estate in the Dordogne that night, but it turned out that Italo Cal vino was in Paris, so they decided to stay over and have dinner. Malle chose the restaurant, Le Quai des Ormes, on the Right Bank, overlooking the Seine—an easy walk from the apartment they've sublet on the lie de la Cite. He was in a relaxed mood; his latest film, Alamo Bay, was scheduled for release in New York within a few weeks, but it was that grace period just after a project is finished and before the reviews have come in, too late to make changes and too early for the critics' verdict. After nine years in America, Malle had come back to Paris for a few months "just to see how it is." For now, he was "having fun"—visiting friends, spending time in the country, screening Alamo Bay. "We were going to go to Venice or go skiing in Switzerland, but Paris is terrific. It's like being en vacances."

I had expected a lot of movie talk, but dinner was like an M.L.A. convention. Affable, gracious, effortlessly polite, Malle has the eager, deferential air of a lyceen sitting for an exam. He talks about books with such intensity that it's hard to remember he's a director; about the difficulties of making a movie out of Calvino's novel The Baron in the Trees ("Amazingly enough, Dino de Laurentiis has the rights. It's the only book he's ever read"); about a conversation between Beckett and Ionesco ("They sit for an hour in a cafe and say two sentences"); about Nicole Stephane's efforts to persuade him to direct Swann in Love ("I went back and read it over again, which was the worst thing I could have done, because it made me realize the whole project was unnecessary"). Not the kind of talk you hear around the pool at the Beverly Hills Hotel.

Calvino, shy, diffident, unworldly, has the old-world manners of an English teacher at a girls' school in the Berkshires. He's spending the next year at Harvard, giving the prestigious Norton Lectures, and he's worried; his precursors—T. S. Eliot, Lionel Trilling, Igor Stravinsky—have set a high standard. He hasn't decided what to say. Mrs. Calvino, an elegant, vivacious woman with strong opinions, is apprehensive about Cambridge; she wants to meet "people, not writers." Malle is acerbic about a well-known director: "You must never phone him," he cautions, "because he'll think you want something." Two famous men at a dinner table usually means a lot of subliminal competition, but Malle and Calvino defer to each other like the two old cronies in Pinter's No Man's Land. Courtly and soft-spoken, they display the attentiveness of powerful people who have trained themselves to listen to others.

Candice Bergen has no trouble keeping up. Unlike the models she derides in her well-received memoir, Knock Wood—"exotic, long-limbed girls'' who arrived for work with "the entire Alexandria Quartet, the complete works of Dostoevski in paperback, a volume of Kierkegaard"—she actually reads books. She's been making her way through Hemingway, and can hardly believe how bad parts of For Whom the Bell Tolls are, but she thinks Fitzgerald's Babylon Revisited stories still stand up. She's just finished The Emperor: Downfall of an Autocrat, Ryszard Kapuscinski's book about the last days of Haile Selassie. The Cal vinos have been to see Mary McCarthy; we talk about her work. Only when I'm back in my hotel room thumbing through Knock Wood and come across a photograph of Bergen in Sidney Lumet's film of The Group do I remember she starred in it.

Since their widely publicized marriage in 1981, Malle and Bergen have divided their time between Bergen's apartment on Central Park South, Malle's country estate, and the far-flung locations demanded by two hectic careers. Their Paris pied-a-terre, a duplex atop one of the grand old buildings on the quai aux Fleurs, has a temporary feel; when I was there in February, they'd only just moved in. It's a simple apartment, sparsely furnished with a leather couch and a few contemporary chairs. The walls are bare, the bookshelves in the upstairs room are empty, but the views are magnificent. One window looks down over the flying buttresses of Notre Dame, another across the Seine to the lie Saint-Louis and the floodlit fagade of the Hotel de Ville. "It's a dream apartment," says Candice Bergen; "sinful," according to Malle, who wanted something "a little more discreet."

Their lack of ostentation reflects a grace bestowed by privilege. Malle goes around in old sweaters and rarely wears a tie; he has the neat, informal look of a Sorbonne professor. You'd never guess that he belongs to one of the oldest and wealthiest families in France, owners of a sugar business that has been in operation ever since the Napoleonic Wars; when the Royal Navy blockaded France and cut off supplies of sugarcane from the Caribbean colonies, Malle's great-great-great-great-grandfather on his mother's side marketed a way to make sugar from beets. "You can still see the name on the wrappers: Beghin."

Malle is the third of four brothers. The oldest, Bernard, is a dealer in rare books and incunabula; Jean-Frangois is a stockbroker. Vincent, the youngest brother, is an independent producer who has been living in New York for the past five years; his films include Marco Ferreri's La Grande Bouffe and Dusan Makavejev's Sweet Movie. But it's Malle, the famous one, the eminent director, who is known as le petit. Small and lithe, with curly hair graying at the temples, he has the tentative air of a younger brother used to being bullied. A rapid, enthusiastic talker, he's so candid that you feel like protecting him instead of asking questions. He blurts out his opinion of a director, then regrets it, worries about the reception of his new film, apologizes for being late when he's on time. He's troubled by the description in Candice Bergen's autobiography of his "trim athletic body," his "fine-featured and romantic" face, afraid his brothers will "make fun" of him.

For Malle, Paris is a novelty; he marvels over the city like a tourist on his first trip abroad. "I've been away so long that I feel like a New Yorker here," he told me one afternoon, dawdling over a bottle of Beaujolais in a wood-beamed old brasserie. "When I left in the mid-seventies, the French were still convinced that Paris was the cultural capital of the world. There was a lot of anti-American feeling, a lot of snobbery. But I wasn't ever really comfortable with all that. I've never felt especially French myself. It was wrong casting as far as I was concerned. Stendhal wanted to be Italian."

In a way, Malle doesn't seem French. The gray suit and pullover worn without a tie are Parisian enough; a cigarette dangles, Belmondo-like, from his lower lip. The references to Corneille and Racine, to Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, give off a Left Bank aura. But Malle's lack of chauvinism, his frankness and self-irony betray him for the maverick that he is. He's impatient with the parochialism, the self-absorption, the willed sensitivity of so many French directors: the preciosity of Claude Chabrol or Bertrand Tavernier, the fey romanticism of Eric Rohmer, the sentimentality of Claude Lelouch. "Whenever I come back, they're right where they were when I left." Godard, he says, is "Swiss"—that is, provincial, unworldly, didactic, an heir of Rousseau. "The French have this terrible habit," Malle complains. "They have theories." The film journals, once dominated by Marxism, then existentialism, now talk the language of structuralism. But this intellectual rigor is an illusion, he insists. "The truth is, there hasn't really been any serious culture in France since the end of World War II—and only a Frenchman would disagree."

In the beginning, Malle himself was the quintessential metteur en scene. "When I was thirteen, I announced that I wanted to be a writer, but my brother Bernard convinced me that I should become a director because I couldn't sit still." So he borrowed his parents' 8-mm. camera and started making "pretentious surrealist films" on the family estate in Thumeries. "They were very skeptical about the whole thing," he recalls. "It was as if I'd said I wanted to join the circus." Malle pere expected Louis and his three brothers to join the business, and packed Malle off to the Institut des Etudes Politiques ("where all the French bureaucrats go''). After a semester, Malle transferred to the Institut des Hautes Etudes Cinematographiques, then signed on with Jacques Cousteau and spent four arduous years at sea; he was an assistant on Cousteau's famous documentary The Silent World. Back in Paris, he worked with Robert Bresson on Un Condamne a Mort S'est Echappe. By his mid-twenties, he was ready to strike out on his own.

Malle's early films, however daring, reflected a world he knew firsthand: the world of the haute bourgeoisie. Most of them were shot in Paris; they featured French stars like Jeanne Moreau and—in Vie Privee—Brigitte Bardot; they had the lyrical, ironic style characteristic of the New Wave; they were intensely literary. Le Feu Follet was based on a novel by Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, Zazie dans le Metro on a novel by Raymond Queneau.

Le Souffle au Coeur was suggested by Georges Bataille's Ma Mere. "That was my La Boheme phase," Malle says. "My films were all about being an artist."

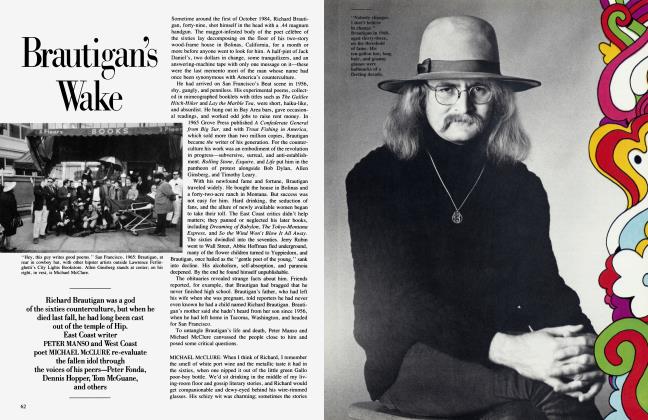

One of the greatest dangers for any artist is repetition, the impulse to copy one's own successes. What's astonishing about Malle's career is its incredible variety. Thrillers, romances, comedies of manners, adaptations of novels: within six years of his debut, Malle had worked in so many genres, been through so many critical triumphs and reversals, that it was hard to imagine where he could go from there. "Barely past thirty," Andrew Sarris proclaimed in the Village Voice, Malle was "washed up in the French film industry."

It was a premature obit. During the next decade, Malle went to India and produced a six-hour television film, L'lnde Fantome; he made Murmur of the Heart and Humain, Trop Humain, a documentary about workers at a Citroen factory near Paris; he created a masterpiece, Lacombe Lucien, the story of how a decent but limited peasant boy becomes a Nazi during the Occupation. He made a surrealist film, Black Moon, loosely based on Alice in Wonderland. By the mid-seventies, he was ready to move on again. "I was bored by my own world," he says. "I needed to revive myself, to do something different. I felt that I'd exhausted what I knew."

America was an obvious choice. Like his compatriots Godard and Truffaut, Malle had been influenced from the beginning by Hitchcock and Griffith, the Marx Brothers and W. C. Fields. For the New Wave, Hollywood was a crucial source. But Malle's preoccupation with America went deeper. "My family was very Anglophile, very interested in everything British and American, and I'd gone to the U.S. many times since college. I was drawn to that Walt Disney culture." Malle is virtually bilingual; only the occasional Gallic inflection ("comfort," "controversy") or an original rendering of some idiom ("I nearly fell from my chair") betrays his nationality. Malle himself is unim-

In the deep of my heart I've always felt I didn't have to make good at the box office.... If you learned to drive in a Bentley, having a Rolls-Royce isn't an ambition.''

pressed with this facility—"Being bilingual makes you a wonderful concierge in a hotel"—but it's clearly enabled him to feel at home in what is, after all, an alien language and culture.

At home, but not entirely at home. "When I came to America I was very much an outsider," he says. "I felt like a displaced person arriving in a new world." It was a while before he found his voice. His first American films, Pretty Baby, set in a turn-of-the-century brothel in New Orleans, and My Dinner with Andre, that garrulous dinner party a deux in which the avant-garde theater director Andre Gregory recounts the particulars of his identity crisis to a credulous Wallace Shawn, were curiously stylized, the work of a director for whom America wasn't entirely real. Even Atlantic City, widely praised for its portrait of the seedy hustlers and hangers-on who populate that squalid town, had an artificial quality. The characters were too predictable— anthologies of American types.

Alamo Bay, which opened last month in New York, is the first of Malle's American films that feels American. Suggested by a 1980 article in The New York Times Magazine about the conflict between Texas shrimp fishermen in the small towns along the Gulf Coast and Vietnamese refugees who began fishing the same waters during the late 1970s, Alamo Bay would seem an unlikely project for Malle. "It's a story about people who don't belong," he says. "Here were these refugees who were just dumped in these little towns by Catholic relief agencies and had to make it on their own. They had come to the end of the line. There was nowhere else to go. And yet it's such a universal fate. The same thing happened to the Jews, the Arabs, the Poles."

Malle got in touch with the author of the article, Ross Milloy, a freelance writer in Austin, but CBS had already optioned it for a TV documentary. Two years later, the option lapsed and Milloy called up Malle, who flew down to Texas to have a look around. "It was a strange experience," he recalls. "There was something very raw about that whole subculture. It's a real six-pack society: Macho Country, men with a big gun and a big heart. But they're very polite; they have actually good manners. You'd show them the script and they'd be horrified by the four-letter words: 'We would never say that.' "

Touring with Milloy and Alice Arlen (Nora Ephron's co-author on Silkwood), who was writing the screenplay, Malle interviewed fishing wardens, filmed locations with a video camera, hung around bars in the port towns on the coast. "He's absolutely fearless," Arlen says. "He would drive into these rough little towns with one main street and explain that he was a French director, and suddenly people would be talking as if they'd known him forever." Getting up at dawn, driving all day in a hot car, Malle exhausted everyone. "His energy is unbelievable," says Arlen. "He has more enthusiasm and curiosity than anyone I've ever known."

Why is a scion of one of the wealthiest families in France, who drives around Paris in a BMW and dines out in the finest restaurants, who numbers among his friends descendants of the French aristocracy satirized by Proust, drawn to such gritty themes? "I think my main incentive in becoming a filmmaker was to deal with people and cultures I wouldn't know otherwise. I mean I wouldn't want to do a comedy of manners about people in New York. Maybe it's the classic rebellion against a strict Catholic family upbringing, but I love to make people feel provoked and disturbed and threatened."

On the set, Malle is known as a meticulous and innovative craftsman. ''He's very chancy, very risky," says John Guare, who wrote the script for Atlantic City. ''He wants to lead you to the most dangerous areas." Yet there's nothing haphazard in his method. Every scene is worked out in advance. Even My Dinner with Andre, which gives the illusion of spontaneity, was rehearsed over and over, then videotaped and studied before it was filmed. ''He doesn't have any ego about listening to suggestions—even if they come from totally unqualified people who happen to be passing through the room," says Wallace Shawn, whose cameo appearance as a waiter in Atlantic City led to the making of My Dinner with Andre. ''The quality of his attention is exhilarating. I've never known an actor who hasn't loved working with him. You feel there's actually someone watching what you're doing."

Alamo Bay was shot for just about $5 million; Malle and his brother Vincent put the deal together, hired the screenwriter, got Tri-Star to finance the film. He's frugal about expenses, but he does things his own way—a luxury few directors can afford. ''The one great advantage I have is that I don't need to think in terms of public acceptance, ' ' he says. "I have the freedom to fail." Malle's films have never made a lot of money. ''I've actually lost money being a director. I'm less rich now than I used to be." Even Atlantic City was a succes d'estime. But his inheritance is sufficient to support him in the style to which he's accustomed and to finance his own production company. By putting up the initial investment himself, he can skip the development-deal stage, and he never has to work on projects that don't engage him. "Movies require a considerable investment," he concedes. "In the deep of my heart I've always felt I didn't have to make good at the box office. I wasn't in it for the money. If you learned to drive in a Bentley, having a Rolls-Royce isn't an ambition."

Still, like any director, Malle is dependent on the major studios for backing: "I'm not that rich. No one is." For Malle, the emphasis on blockbuster films is an ominous development. "Movies are a business here, much more than in France, where they're still considered art. Hollywood is only interested in big money-makers." In his view, the invention of the videocassette has been a disaster: "Cinema as a medium is just about obsolete. The

as a medium -SOIete The IS Just Tbere hasn't really been any serious culture in France since the end of World War IIand only a Frenchman would disagre~'

only people who go to the movies anymore are kids who want to neck— the children of Animal House," he complains.

"People like me are practically out of business."

One project of Malle's that never got made was a film about the Abscam congressional scandal. John Guare had written a script, called Moon over Miami; John Belushi had agreed to play the con man who introduces bribe-susceptible congressmen to an F.B.I. agent posing as an Arab sheikh. (Dan Aykroyd wanted the part.) "Hollywood won't go near anything political," Malle says. "If it hadn't been for Belushi's name, no one would even have read the script. Everything else about it scared them to death." When Belushi died, the movie was shelved.

Malle is endlessly fascinated by America, and his films are becoming more American every year. But there's a unity within the incredible diversity of his career. In a certain oblique way, his French films parallel those made in

America. Lacombe Lucien, like Alamo Bay, was about what happens to people when they're caught in the clutches of history. Some of the peasants and petty bureaucrats he depicted were evil, some courageous, but most were just ordinary citizens overwhelmed by events beyond their control. The collabos and those who joined the Resistance turned out to be very much alike. In the same way, the K.K.K. vigilantes who terrorize the Vietnamese in Alamo Bay

aren't just redneck thugs; what makes them vicious is the threat to their livelihood. For Malle, morality isn't absolute; how we behave depends on how life tests us.

How does he think his new film will be received in Paris? "I'm not optimistic. They don't exactly love me here. You're thought of as a traitor if you live abroad. I'm so identified with America that when I run into people I know here now they

say, 'Louis Malle still speaks French!' " Maybe so, but the phone in his Paris apartment rings off the hook. There are calls from old friends, new

friends, people passing through; neither Malle nor Bergen seems to have dropped anyone they've ever known. One afternoon it's the wife of Jack Lang, the minister of culture. Can M. Malle come for lunch next week? "Le ministere? Le douzieme? Bien sur."

That weekend they were off to Malle's chateau—"an extraordinary house," Bergen writes in Knock Wood,

"one of the oldest in the area, medieval in style and mysterious in aspect, built of buff-colored stone." It was there that she and Malle were married, and her

account of how they fell in love is right out of Hollywood. For all her stunning beauty, her wealth, talent, and celebrity, she had problems with men. There was a famous producer, a childhood sweetheart (Terry Melcher, the son of Doris Day), a Brazilian radical, an Austrian count— even a date with Henry Kissinger. They were all Mr. Wrongs. Unmarried at thirty-four, she had just about given up on ever finding anyone when she was introduced to Malle by Mike Nichols at a Fourth of July party in Connecticut. After a timid and protracted courtship, Malle finally proposed, and they lived happily ever after. "I am grateful for the miracle of my marriage," Bergen's memoir concludes, "that we managed to find each other, that we get to begin our days together, share our lives together, respect each other, support each other and let the other be."

Malle, who has two children by other women (his first marriage was childless), isn't quite as reverential as Bergen; he once complained to a reporter from Time that living with her while she was working on Knock Wood was "like being married to Flaubert." It's not his favorite subject, "/'m going to write now," he interrupted one day when I was going on about her book. "I'll call it Sugar Babies." But he, too, has declared his marital bliss in the press, and they do seem utterly happy. Their marriage, friends say, is "perfect," "secure," "terrific"; on two separate occasions, I heard it characterized as "brilliant." "They surprised a lot of people," says the literary agent Ed Victor, who has known them both for years. "They're a very attractive couple—famous people who somehow never got it right in love. Candice needed a good man, and she got one." Do they plan to have children? I asked Malle one afternoon on the way back to their apartment. Bergen walked ahead. "It's complicated," he said. "There are a lot of.. .logistics." Apparently the matter hasn't been resolved.

Bergen's diffidence complements Malle's own. Despite the life of luxury described in her memoir—the attention lavished on her as the daughter of the celebrated ventriloquist Edgar Bergen; a Beverly Hills childhood that featured rides on the miniature train Walt Disney had in his backyard and Christmas parties where Charlton Heston played Santa Claus; Swiss finishing schools; a successful career as a model and eventual stardom—Bergen is hesitant, withdrawn, the silent wife. She's reluctant to talk about herself; it's bad manners. She was off to London at the end of the month to star in a CBS TV movie produced by Lawrence Schiller (he put together the deal that resulted in Norman Mailer's nonfiction novel, The Executioner's Song), and she'd just been in Hollywood Wives, but she maintains that she "hasn't been doing much of anything," and feels guilty about it. "I know you're not supposed to say that."

Not only doesn't Bergen act like a movie star, she doesn't seem to like performing, and her reluctance comes through. Ever since her debut in The Group, she's gotten decidedly mixed reviews. Pauline Kael, who interviewed her for Life while The Group was being made, was not impressed. The young Bergen, she conceded, was "a golden lioness of a girl," but she simply wouldn't act: "Here she is, an intelligent young girl, beginning—despite her disclaimers—a career in the movies, and she doesn't appear interested enough even to stay awake and observe." Seven years later, she was still in a somnolent state: "Miss Bergen performs as though clubbed over the head," said the New York Times of her performance in The Adventurers. It still happens. "Miss Bergen does some acting," John Corry, a Times TV critic, wrote last February of Hollywood Wives, "but never again are you likely to see an actress look so uncomfortable while she does it."

No one is more disparaging about her career than Bergen herself. Knock Wood is a chronicle of missed opportunities and disastrous performances. "She was wonderfully confident, or seemed to be," Sidney Lumet recalls of her performance in The Group. "If she was unsure of herself, it didn't show." In Bergen's recollection, Lumet had to coax the part out of her; being in front of the camera was an ordeal: "I was playing enough parts in real life." It wasn't until the more freewheeling roles of her thirties—the frustrated housewife who tries to become a singer in Starting Over, the bitchy southern belle in Rich and Famous—that she learned to relax and enjoy herself.

What's remarkable about Bergen is her lack of vanity. "Being that rich, beautiful, talented, and famous is an occupational hazard," says Ed Victor's wife, Carol Ryan, a lawyer in the film industry who has known her for years. "It intimidates people, and Candy's worked hard to correct for it." Once you've gotten used to the face that was on the cover of Vogue, the face you remember from Carnal Knowledge, she becomes just another anxious writer, amazed that anyone would like her book.

I was sorry to leave Paris. 1 would have liked to stay on, hanging around the apartment on the quai aux Fleurs and watching the tourist barges float by down below on the Seine. But I had to get back. Loitering in a cafe on my last afternoon, I noticed a familiar name on the packet of sugar I was unwrapping. "Beghin," it said, "Sucre morceaux."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now