Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowVISUAL ARI

Comic Strip Teasers

Kristine McKenna

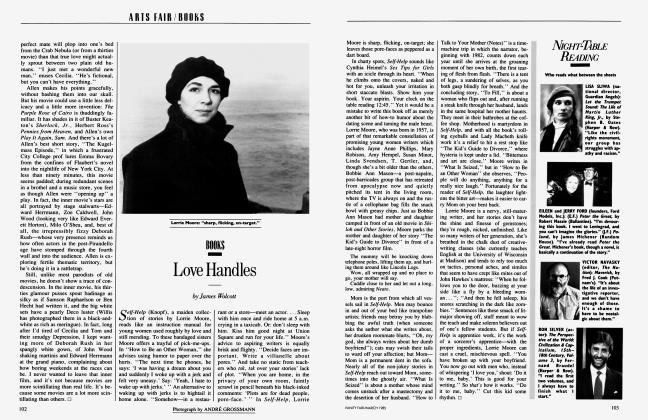

"Fanaticism of any sort is encouraged in Los Angeles," observes cartoonist Georganne Deen. "There are people here who spend their entire lives perfecting a single skateboard trick." As a child growing up in Texas, Deen recalls, "I was always drawing bunnies and lobsters, then putting big tits on them," and she continues to conjure demented mutations—regally clothed insects, Mr. Potato Head at the wheel of a plush convertible, spooked littie kitties she refers to as hypoglycemic cats.

Though Deen makes the bulk of her living as an illustrator, she, along with fellow West Coast art mavericks Matt _ Groening, Lynda Barry, Gary Panter, and Raymond Pettibon, is usually referred to as a cartoonist. High-art power brokers have tended to give cartoonists the bum's rush out of the art world whenever they've tried to elbow their way in, but things are changing on the cheap-white-wine circuit. In the sixties everything was up for grabs, in the seventies punk was the entryway for cultural provocateurs, but in the eighties it's all about power and money. Nonetheless, at the same time that the art world is constricting, its scope is broadening. So magnanimous has the scene become, it's even able to accommodate cartoonists. Works by Barry, Panter, and Groening were showcased in an exhibition titled "Art and Products" at the Bella Via Gallery in Los Angeles last December. In November, Panter had a show at the Tilden-Foley Gallery in New Orleans, and Barry at Seattle's Linda Farris Gallery. Pettibon recently had a solo show at the Zero One Gallery in L.A., and New York's Semaphore Gallery will show his work this spring. This is not to imply that anyone who aces the "Draw Me—You Too Can Be a Cartoonist!" challenge is headed for the walls of the Whitney. These five are not run-of-themill joke sketchers; they have bigger fish to fry.

"Traditionally, comics have pandered to readers' prejudices, but Lynda Barry and I try to undermine those prejudices," says Groening. "We do comics on subjects that people feel extreme anxiety about—sex, death, love, and work, topics that aren't usually addressed in cartoons." Groening's weekly strip, "Life in Hell," often culminates with his central character, an obnoxiously cute bunny named Binky, hopelessly lost in a philosophical maze. Pettibon's single-frame cartoons don't deliver a punch line so much as point a pistol at the reader.

In their late twenties or early thirties, all five came of age with Johnny Rotten; it's been a good five years since punk was cast on the junk heap of obsolete cultural movements, but _ its presence continues to be felt. "Punk was real important for me graphically," observes Panter. "Punk validated a style I've spent my entire life being criticized for liking." Unlike that of the underground comics of the late sixties, and the National Lamp oon-Satur day Night Live crowd, this group's worldview is neither drugged nor smug. Yet they manage to circumvent the dreary self-consciousness of the Jules Feiffer ironic-cartoonsfor-adults school. "The Lampoon had a meanspirited, elitist, conservative, white, college-boy mentality that I never liked," says Groening, whose strip is syndicated in forty-two newspapers in the U.S. and Canada, giving him the highest visibility of the five.

The adolescent zaniness of Mad magazine is more to Groening's liking, and his strip flip-flops between fits of nit-picking and gleeful silliness. Lynda Barry, whose strip appears in Esquire niagazine, speaks in a similarly goofy voice. Her central themes are the secret rituals that enable one to present a cool face to the world, and love in all its permutations.

Thesefive are not run-ofthe-mill joke sketchers; they have bigger fish to fry.

While Barry drifts through life in search of a surefire diet and a teenage dreamboat, Raymond Pettibon gropes through a sixties nightmare. Exploring the hideous dregs of the Love Generation, his drawings are peopled with the kind of human sludge you'd expect to see hitchhiking on a freeway on ramp out of Vacaville. Depicting dazed hippies fried on drugs, runaways with dirty hair and vacant eyes, cultists, fake messiahs, assassins, and racists, Pettibon suggests that the American Dream isn't all that it's said to be. His aesthetic seems to be fed on hard-boiled-detective novels and the kind of lurid crimes covered in the National Enquirer. But Pettibon claims that subject matter is irrelevant, that it's the juxtaposition of words and image that distinguishes his work. He has a point. With jolting punch lines like "I didn't start taking my father seriously until he killed himself," any accompanying image would resonate.

Like Pettibon's, Panter's work gives off a threatening, high-voltage hum. Wrapping a sweetly melancholic sensibility in a drawing style so rough and jagged that it verges on abstraction, Panter pairs text that is often indecipherable with drawings fed on a love of visionary folk art, Elvis Presley, and Disney. An avid collector of toy robots, Panter is hugely successful in Japan; it's odd that the Japanese respond to cartoons so subtly and distinctly American.

Bom in a fit of punkish annoyance, these cartoons seethe with anger at forever being tripped up by an astonishingly stupid world. Within the same strip, the protagonist/victim wises up and gains a sliver of insight into the root of the problem: Something tells me there's an asshole on the premises, these cartoons seem to say, and I have a feeling that it's probably you and I both.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now