Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA SHORTER "DAY'S JOURNEY"

Jonathan Miller talks to DAVID RIEFF about cutting down to the quick of O'Neill

DAVID RIEFF

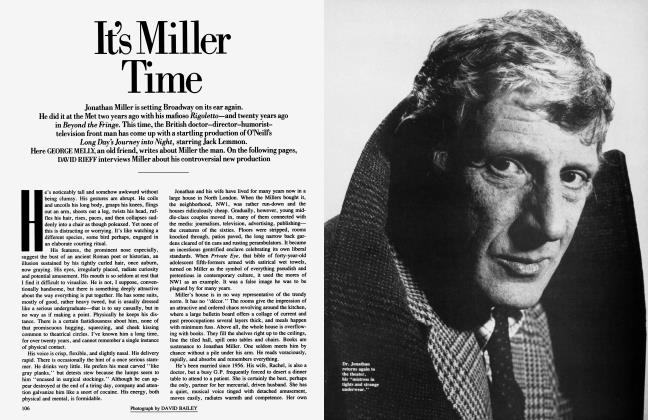

Jonathon Miller's new production of Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey into Night, starring Jack Lemmon, has just opened at the Broadhurst Theatre in New York. Miller is famous for his controversial stagings (when he took over a series of televised Shakespeare plays, a BBC executive was heard to moan, "I hope he's not going to do them underwater"), and his Long Day's Journey is unlike any previous version of O'Neill's masterpiece. The classic American story of the Tyrone family becomes "a fast-moving, rather bitter play which has got great magnitude because of its realism, not because of its majesty." Miller lets the characters interrupt one another and speak at the same time. Their lines mesh together hypnotically. This cuts down on the notorious length of the play (his version clocks in at two hours and forty-five minutes), but the audience misses nothing: all the lines are there, starker for having to compete. During a break in rehearsals, Miller spoke about his work.

Long Day's Journey into Night is the first modern play you've done in a while.

Yes. I did an Osborne play when I began directing, and I've done Chekhov's Seagull and The Cherry Orchard, which are almost contemporary. Of course I've been out of the theater for a long time, by default really, because there have not been any plays for me to work in. Being shut out of the National Theatre because of my row with Peter Hall and not being able to go to the Royal Shakespeare Company because it's a closed shop had the effect of turning me toward opera. But I found that I missed being able to play around with

the inflections and intonations of language. Music gives you this impermeable membrane where you can actually press through and alter shapes of words, but one can't get direct access to them. Music surrounds the words.

What special problems did this play pose for you?

The strength of Long Day's Journey into Night is that it is real. However, even though it was written comparatively recently, in the 1940s, it has acquired a terrible thick varnish of sentimental grandeur. For a start, the characters have become sacred characters. Mary Tyrone is thought to be inseparable from the playwright's mother. She is also the heroic Mary Tyrone of the American stage, so that she has two biographical existences; she is sacred in her role as O'Neill's mother and she is also sacred as the person who was played by Florence Eldridge and Kate Hepburn and Constance Cummings. Now, I think she is sacred for neither of these reasons—indeed, she is not sacred at all. She is a fairly vague space into which a number of claimants can slip. By claimants, I mean people who lay claim to being Mary Tyrone. The problem, of course, is that people who are committed to the notion of there being an actual Mary Tyrone are obviously going to object to almost any interpretation as being a flawed version of the actual one.

But you know, people don't say this sort of thing just about a character like Mary Tyrone; they say the same sorts of things about characters for whom there is no biographical pedigree at all. For example, although there is no actual Hamlet upon whom Shakespeare based his Danish prince, there are all these actors. People say, Well, that's not Hamlet, by which they mean that's not the Hamlet to which they've become accustomed because of the previous impersonations that have claimed their allegiance.

I set out to present this play as engagingly, as amusingly and interestingly as I could, knowing perfectly well that there were things which might easily defeat that purpose, one of which was the famous length of the play. I sometimes think people have confused its length with its title and now assume that if it's not four hours long then it cannot be a long day's journey into night, as the title implies. Many people endure this ordeal in the belief that they are seeing the great American play and feel virtuous as a result of having stuck it out rather the way they stick it out in Bayreuth. But it's not a Wagnerian work. If I set out to do anything radical, and I think I was very reticent, it was because I was determined not to be subordinated by claims that the play was Wagnerian, Greek, Sophoclean, or whatever. The Tyrones are not the House of Atreus.

The expectations you describe people as having about this play strike me as sentimental. It seems that much of your work is meant to correct certain sentimental ideas about great works of art.

I think I have had a certain interest in, or appetite for, something which is slightly stripped down and a little bit bleak. There is a theatrical sentimentality that has grown up around works which we have inherited from the past and which people now think of as being a canonical representation of the period. The exemplary form of opera production, for example, is the style adopted by famous, grand, and glamorous houses like the Metropolitan in New York, the Hamburg State Opera, Covent Garden, and Paris. Somehow the spectacle has to come up to and justify the aesthetic expectations of the patrons of these houses, who are often conspicuously ignorant of how things might have looked and who are also indifferent to real art. They seem to want to be able to applaud the scenery, and what solicits their applause is, in fact, tremendously sumptuous, heavily embossed period detail or what they think of as period detail, and I think that stops one making art. The work becomes floridly moribund.

But you pay very close attention to historical detail.

I certainly don't do anything from the classical period without paying close attention to the way in which things might have looked at the time. When I'm doing nineteenth-century works I will use a great deal of photography. When I did La Traviata many years ago, I wanted to get away from that way of doing the work which is epitomized by the flamboyant vulgarity of Zeffirelli's version, which seems to be taking place in something that is a mixture of a party at George Weidenfeld's and a reception at the British Embassy in 1968. The truth is that if I'm seen as some kind of Cromwellian destroyer of images, it's not because I want to destroy beauty or ruin romanticism, but because I'm interested in trying to strip away these sentimental Victorianisms which have outlived the nineteenth century by many years.

I suppose that if I were forced to identify some common theme in my imagination that was shared by all departments in which I work, I would say that science is the paradigm. I was taught that there's no room for sentimentality in science: you just simply find out how things work. Now, I'm not so naive as to think that there is such a thing as how things were, but there are ways how things couldn't possibly have been. I think it's advisable to eliminate those. And at least by stripping back to something much less ornamental, much less florid, much less sentimental, you can actually make a better guess at what the truth might have been.

You have said that the confusion that surrounds the theme of O'Neill's play and the confusion that surrounds King Lear are somewhat similar. Well, both plays are always assumed to be titanic, and audiences are frequently disappointed if they don't get a sort of elephantiasis of the drama. But King Lear is not written on a Wagnerian scale. And James Tyrone is not Lear. O'Neill wrote a play about a hermetically sealed family that has no friends because of the life that is led by this poor, probably second-rate, actor, James Tyrone. It's fascinating to me that the sons never have girlfriends. All they have is whores. And who does Tyrone meet except second-rate Irish politicians in the Blarney Bar up in New London? You can't make majesty out of that, but you can make tragedy out of it.

The strength of Long Day's Journey is that it is most like conversation. The play is about actual life—by actual I mean not the life of the actual Tyrones but something recognizable, a family speaking fast and bitterly on top of one another, with that volatile iridescence that ordinary conversation has, instead of being a series of set pieces.

The Tyrones seem so alive in your version. Can you imagine them today?

I can imagine them contributing money to Noraid, on occasion sentimentally singing "Wrap the Green Flag 'Round Me, Boys," and on Saint Patrick's Day riding in a float along with one or another of the I.R. A. leaders. It seems to me enough to be tragically real rather than to be monumentally tragic.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now