Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPHOTOGRAPHY

Old Master Prints

Clegg & Guttmanns double takes

ARTS FAIR

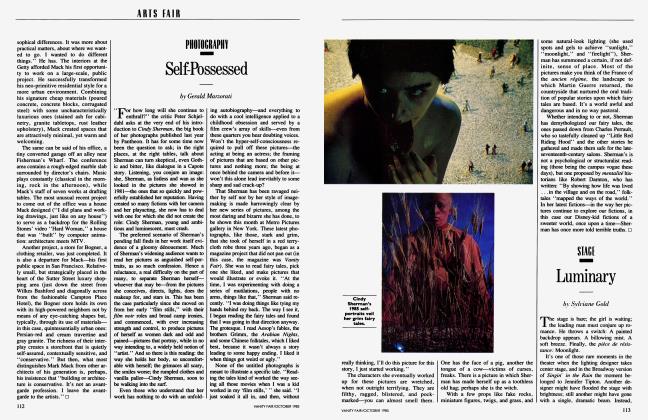

The Bronsteins were dressed up and fidgety and a little apprehensive— which is just how Clegg & Guttmann expected to find them.

"When we do commissions, there is the problem of our wanting to get at something, and those being photographed wanting something else," Martin Guttmann had said at lunch the week before. "We are interested in the things that have always been there in portraits, since the 1600s. How are people represented? Who controls the meaning, the sitters or the artist?"

"It's complicated," Michael Clegg said.

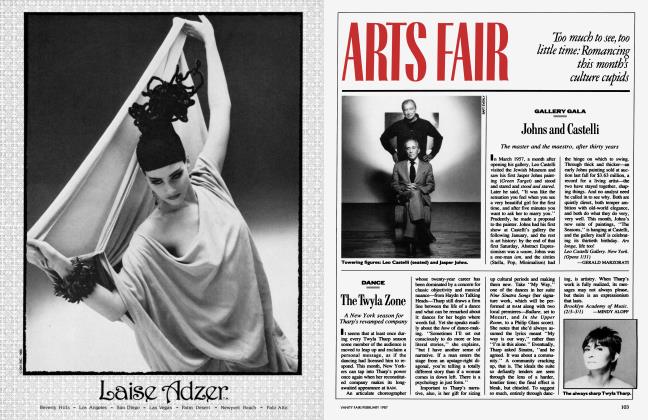

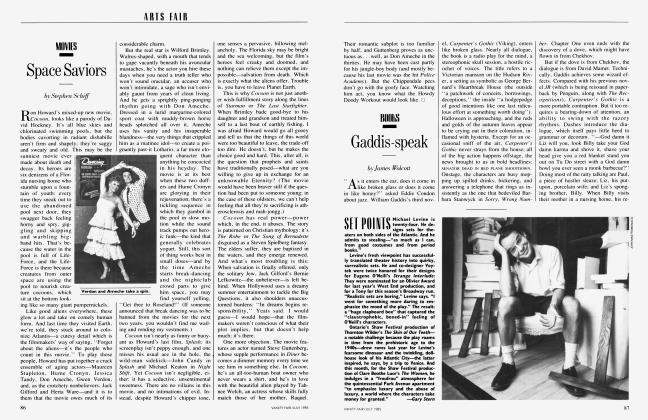

The Bronsteins, in the foyer of their apartment on Manhattan's Upper East Side, were five: Peter, the successful divorce lawyer; Jean, his wife; and their three boys, Charles (eleven), James (nine), and Frederick (two). Clegg & Guttmann (both twenty-eight) are one, an art team in the nascent tradition of Gilbert & George. They do commissioned photographic portraits. Or, rather, they do "commissioned portraits" the way Cindy Sherman did "film stills"—they make pictures that at once use and sardonically abuse certain conventions of representation. Their portraits are studies not of the persons posing but of the pictorial tropes —established hundreds of years ago and long atrophied—of pose itself. To look at a Clegg & Guttmann portrait is to be seduced just long enough by the chiaroscuro, the burnished realism and stolid expressions of the sitters, to see these effects as effects.

They used to hire actors to sit for their portraits, which they began to make in 1980 and have since shown in New York at Nature Morte and the Cable Gallery. Most of these pictures are takeoffs on the hushedand sombertoned portraits of executives from the pages of corporate reports. Lately, the artists have branched out into what might be called genuine fake commissions; approached by someone who has seen their work, they agree to do a photo session, but make no promises.

While Clegg & Guttmann unpacked their equipment (a four-by-five view camera and two cheap spotlights), Peter led me into the dining room. "The portrait—it will be two panels, and lifesize, as I understand it—will hang in here, on either side of the fireplace," he said. "I'd thought of having it in my office. But being a divorce lawyer, it would be a little funny, a large portrait of my family, and the clients, with their families breaking up. . . "

In the living room, Clegg & Guttmann set about tacking to a wall the backdrop they had brought along. Behind their sitters they always hang a huge photographic blowup of a stately room or a grand hallway they've visited and photographed. When used as backgrounds, such spaces were thought by the Dutch painters to lend a picture timelessness and repose; today they lend ads and prime-time melodramas a look of art, an old-master gloss. The blowup for the Bronstein shoot, blue-black and dramatic as night, was of a suite of floor-to-ceiling windows. Clegg & Guttmann had found them in a YMCA in Jerusalem—the city where they got to know each other in an afternoon art class fourteen years ago.

The backdrop in place, Clegg & Guttmann turned their attention to wardrobe. Charles and James were to change into white shirts the artists had brought along— purposefully too big because, Clegg had said, "the imperfections are so important." Blue blazers for the older boys, fine. Frederick's little sailor suit, fine. Peter was O.K. in a dark suit, but the tie had to go. "He's a lawyer," Guttmann said. "He must own a striped tie."

The first photograph, to become the right-hand panel of the portrait, would be of Jean, James, and Frederick. In the cab, on the way to the Bronsteins' apartment, Guttmann had shown me a photocopy of Goya's Holy Family—the idea for the composition. "Every age has to invent portraiture, but it's really more like reinvent," Guttmann had said. "And that's pretty easy with photography." In the living room, Jean sat before the dark backdrop with her children at her side; her face was bathed in the light that had shone down on the Virgin, then the queens and ladies at court, then the wives of the burghers of Amsterdam. "Are you sure that light isn't too harsh?" Peter said. "I'm not sure that it is so flattering."

A little later, Peter posed for the lefthand panel with his eldest son. He removed his glasses, adjusted and readjusted his hands, crossed and uncrossed his legs. "What kind of expression do you want? Smile? Look aggressive?"

"Opaque," Clegg said, and a certain intensity drained from Peter's face. At the back of the camera, the image could be seen, form and composition accentuated. Clegg studied it, then clicked several times. He and Guttmann had gotten what they wanted; Bronstein stared gently, seriously into the distance—he might have been weighing business matters in Delft.

Gerald Marzorati

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now