Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe RIPE Stuff

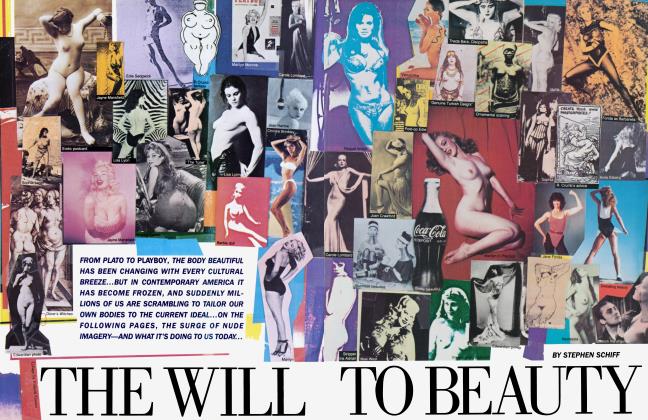

Kelly McGillis, an actress with womanly curves, a beauty in the vanguard of the new voluptuousness, by STEPHEN SCHIFF

STEPHEN SCHIFF

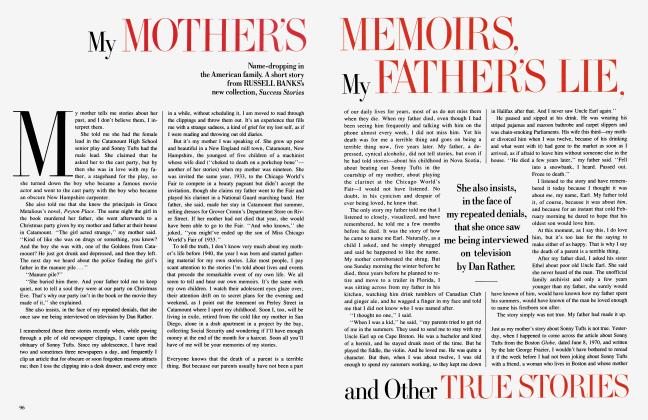

There is a new look in the movies—or rather an old look renewed—and Kelly McGillis has it. When you see her romancing Tom Cruise in Top Gun, you can't help thinking, How can this tall order of vanilla fall for that runty little peanut? She's too much woman for him, no matter how many loops he can loop in his F-14. Kelly is blonde—some days—with the sort of grassy eyebrows you find on so many actresses and models of the last few years. But the main thing is her size. Fully five feet ten, this is a big girl, a strapping, fleshy girl, and she has curves the way Harlow had curves. Not for Kelly the Sharpened-Pencil Look: she will never Nautilus herself to a splinter. "Been lifting weights," she assures me. "Can't you tell?'' I can't. She pulls up her sleeve to expose a woeful flap of biceps, and I shake my head. "Well, for me that's good,'' she insists. And then, pouting, "I'm a girl.''

Just so. Besides the forgettable Top Gun (in which she plays an astrophysicist who instructs fledgling fighter pilots), the twenty-eight-year-old Kelly has made only two movies. Yet when she first appeared on the screen, in 1983's Reuben, Reuben, she already seemed the eighties' answer to Grace Kelly: an expensive-looking blonde whose knowing blue-gray eyes gave her the kind of regal cool the movies hadn't seen since the studio days. Californiaborn and Juilliard-trained. she was a modest, moonfaced creature, still waitressing nights and weekends at J. T. McFeely's in Brooklyn and hoping for more movie work. That was before the director Peter Weir saw Reuben, Reuben and cast Kelly as the Amish widow in Witness—opposite Harrison Ford, whom she matched scene for scene. Kelly's fiercely peremptory gaze grounded her amid the movie's roughspun woolens and wheat-colored light. and she looked like no other heroine in recent film: bullnecked, full in the hips. with a meaty waist and an air of sturdiness that appeared milk-fed and farmgrown—and quite improbably sexy. "In a sense, it was like doing a period movie,'' Kelly recalls, "because of the garments you wore, what they did to you physically. It changes you when you have to go for days without ever slouching around in blue jeans." She's slouching around now in her new West Hollywood apartment, wearing fuzzy black tights and a white T-shirt that could accommodate a Green Bay Packer or two. Her hair is curly and all over the place (a bit of it even turns up in the coffee she serves me), and her boyfriend, the gangly twenty-three-year-old actor Barry Tubb (also in Top Gun), drifts in and out, dispensing wisecracks and sometimes tripping over the furniture. When Barry stumbles, Kelly laughs—or, to put it more accurately, guffaws—but her explosive hoots always subside, quite unnervingly, into the low purr of the compleat femme fatale. Which Kelly's personality in no other way resembles. She's a floppy, rather companionable sort, a big, affable kid poured all unawares into the body of an old-fashioned Hollywood seductress.

No matter how many weights Kelly McGiliis lifts, she'll never be a modernist idealher form will never siniply follow function.

Talking about herself makes her nervous, and she keeps running her hand under her T-shirt, unconsciously stroking her chest, occasionally grabbing great chunks of flesh. These days, it's remarkable to see an actress who has any. I have always been a partisan of the screen sirens of the forties and fifties, the Ladies of the Big Shoulders—Rita Hayworth, Ava Gardner, Jane Greer, Lauren Bacall, Gene Tierney: imposing actresses, women whose appearance at the top of the stairs had a certain riveting grandeur, a certain weight. Ever since forties-style padded shoulders came back into fashion, I've been waiting for the bodies beneath them to return as well. But they haven't. Where shoulders should be, there have been mere clavicles, and the clavicles have been shored up by sinew, and beyond that by pointy outcroppings of sternum and rib. Flesh has disappeared from our vocabulary; the stuff that enshrouds contemporary bones is either muscle or fat, the former deemed good and the latter odious. But with the emergence of Kelly McGillis and a few other stars, a change is in the wind. While luxuriant dreadnoughts like Jessica Lange, Kathleen Turner, Madonna, and Kim Basinger—not a sylph among them—flatten all comers, the celebrated fashions of the designer Azzedine Alai'a transfigure the plushly upholstered body. Lushness is sexy again; the Skinny Minnie chic that dominated the seventies has toppled.

"I still don't think I'm beautiful," Kelly protests, and means it. Overweight in high school, she claims that her self-image now is based on how she looked then. "I was too big, and that always made me feel like a loaf." But this is 1986. It was the seventies that condemned fleshiness—along with every other cover-up. The very notion of concealment became revulsive to Americans; we'd had too much Watergate, too much Love Canal, too many dirty tricks. Americans showed their distaste for secrecy not just by electing the inept yet doggedly honest Jimmy Carter but also by chasing after natural fibers and natural foods and natural let-it-all-hangout therapies. Women no longer wanted their outsides to hide what was inside; for the first time in memory, they wanted their muscles to show, and their bones and veins.

The female body, all scapula and deltoid, became a sort of organic version of the Pompidou Center, its tubes and tendons thrumming away in the open air. But no matter how many weights Kelly McGillis lifts (and one gets the impression that her regime is not exactly draconian), she'll never be a modernist ideal—her form will never simply follow function. Lucky thing postmodernism is upon us. Decoration has become desirable again; the new White House is better at pomp than at circumstance; buildings and fashions and design have all succumbed to the allure of allure. The come-on is back; we've rediscovered the ancient verity that concealing a little is sexier than revealing all. Hence the return of flesh, that most beguiling of cover-ups, that most seductive of advertisements for our Self. Kelly McGillis's time has arrived.

In Top Gun, she looks splendid, towering over the macho mites she's supposed to be teaching, slouching moodily in doorways like the black widow in a film noir, sending tough guys spinning with a steamy glance. Top Gun may be the palest summer hit in memory, but Kelly McGillis has the ripe stuff.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now