Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDivine Demuth

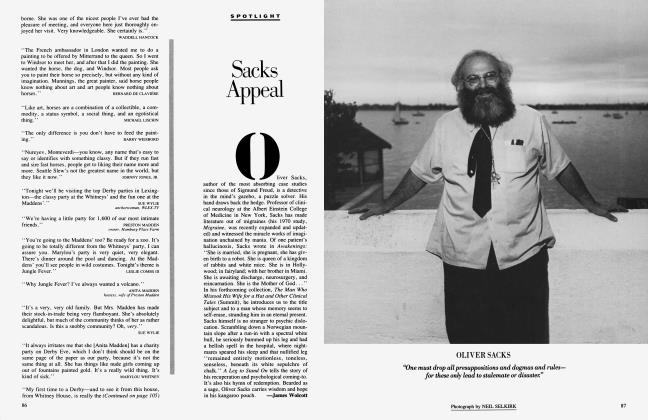

Charles Demuth painted in the right places at the right time, yet, as his friend Marcel Duchamp remarked, "he didn't care where he was in the social scale." Perhaps that's why RICHARD MERKIN finds Demuth's work—now at the Whitney in a rare retrospective—so prophetic and unselfconsciously original

When it comes to art, we have always preferred our butchers {p our accountants: from Marin to Pollock to Schnabel, the chest beaters have captured our imagination more than the quiet, rarefied achievers. Despite over five decades of recognition as an "artist of historical note," Charles Demuth has been one of those artists for whom we've always been a day late and a dollar short. This month, the Whitney Museum in New York opens a pungent and grand retrospective of this complex man whose touch was angelic and who called painting "the 'nth whoopee of sight." In today's cacophonous art world, Demuth's glorious multiplicity of styles, long an impediment to his appreciation, may at last be fully comprehended.

Demuth's best pictures always have a secret meaning, a kind of doppelganger, that distinguishes them from the colder, bolder, more accessible work of his contemporaries John Marin and Charles Sheeler. The astonishing I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, a tribute to his friend William Carlos Williams, not only refers to one of the poet's lines but becomes an independent metaphor for 1920s urban energy. My Egypt, the austere landscape of industrial Lancaster, Pennsylvania—where he was bom in 1883—also refers ironically to Demuth's confinement there after severe diabetes forced him, at thirty-eight, to move back. And his lush floral watercolors often bear eccentric, literary titles. Demuth's pictures, tantalizingly elusive, always suggest more than that which meets the eye.

His life was also dichotomous, poised between aloof propriety (his patrician, devout Lutheran family) and his hedonistic, worldly instincts. After a somewhat overprotected childhood—he was lamed by Perthes' disease, a hip ailment—Demuth attended Philadelphia's prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he painted earnestly in the expected mode of the Ashcan School. But he was truly mesmerized by nineteenth-century Aestheticism ("Art for art's sake"), and parted his black hair a la Aubrey Beardsley. Like Oscar Wilde, whose writings he fervently admired, Demuth probably reserved a significant part of his genius for his life. He was decidedly homosexual, strikingly exotic if not handsome, and always impeccably clad. In life, as in his pictures, he sought the perfect pose. (In the sixties I fell heir to his cigarette case, bequeathed originally to the designer Robert Locher, the onetime lover and lifelong friend of Demuth. It was, of course, black and gold and Mark Cross.)

At home in Paris and New York, Demuth was socially successful and mingled easily (including in the chic New York salon of the Stettheimer sisters) with a grace that Wilde would have admired. He was an intimate of Marcel Duchamp—the two exquisites formed a mutual-admiration society—and a key member of the circle around Alfred Stieglitz. Although more flaneur than bold participant, Demuth frequented nightclubs like Barron Wilkins's and Marshall's (run by blacks and catering to a clientele with liberated morals), the sub-rosa Turkish baths, and, on occasion, les petits theatres du rough trade. Surely the least exhibited Demuths are the clandestine, erotic works he painted throughout his career.

"The locality is the only universal,'' the philosopher John Dewey proclaimed. Despite Demuth's physical deterioration, his robust paintings of the thirties achieved that universality by brilliantly splicing the lessons of Cezanne and Cubism onto the Lancaster skyline. With glowing color, subtle wit, and unerring composition, he took his local monoliths—factories, smokestacks, water towers—and made of them images that are timeless and thoroughly American.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now