Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAmerican Buffaloes

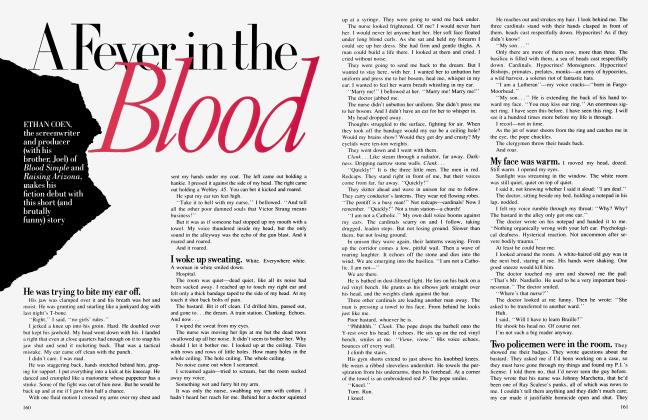

BRUCE WEBER

BRUCE WEBER photographs a Mount Rushmore of Hollywood tough guys.

PETE HAIL

Images of these men have been part of my life since I was a small boy. They are firmly inlaid in that part of me that is imagined, unreal, melodramatic, and oddly gorgeous, the gleaming region of lies that were more deeply experienced than real life. I look at their faces now, in these extraordinary photographs by Bruce Weber, and it's clear that all of them are moving to the sunset. But if that is so, then I am too. We've traveled a long way together. And I search memory for the moment when 1 first saw them, on lost afternoons when all of us were young.

In a flash, I am in the turbulent darkness of the Minerva Theater in Brooklyn, the air stained by the odor of a backedup sewer, and I'm watching Red Ryder gallop through the odorless, bone-clean canyons of the American West. With him is Little Beaver, and I don't know then that Little Beaver is Robert Blake. He is just an Indian kid, my age, and I wish that I could have his job, pursuing villains in a clean and empty place. This was the time when movies were glimpses of other worlds, beyond the tenements; they were not yet the products of producers, directors, screenwriters, or actors. Little Beaver was as certainly Little Beaver to me as Baretta, more than thirty years later, to a ten-year-old, would be clearly, firmly, and permanently Baretta.

Now I'm in the Globe, and I am rooting with my hoodlum friends for the sleepy-eyed villain to take out Hopalong Cassidy, who we believe is the greatest putz in the West. The villain walks better than Cassidy, he talks better, his eyes never open in fear or alarm. We don't know his name is Robert Mitchum. We don't know that the same Mitchum is also the dirty, sweaty, cursing Lieutenant Walker in The Story of G.I. Joe. He just is a soldier. Real.

We're in the Sanders a few years later, or the Venus, or the Carlton, and a fighter named Midge Kelly is snarling his ferocious way to the middleweight championship of the world. This is Kirk Douglas, but in the darkness we're matching him against Sugar Ray Robinson or Rocky Graziano and we don't think he could go three rounds.

It's a few years after that. We're older, we go to the rowdy neon palaces of Forty-second Street, and we know now that movies are made by human beings and not snatched from the air by magic. The picture is The Day the Earth Stood Still. The guy with the furrowed brow, the pained look, the intelligent eyes, the quality of doubt—that's Stuart Whitman. He never becomes a star; he is more like us in some way, part of the blur, but always there.

He is certainly not the man we saw one night in 1947 in the RKO Prospect. We were watching a movie called Kiss of Death, and a scary gangster named Tommy Udo was kicking a grandmother down a flight of stairs. He was blond, with dangerous eyes, wearing a wide-brimmed hoodlum hat and a white tie on a black shirt, devoid of loyalty, even to his friend Victor Mature. This was Richard Widmark, and years later, when I was in a New York bar talking to Joey Gallo, who was a real gangster, he told me that the most important event of his young manhood was seeing that movie. "I copped all of Widmark's moves," Gallo said. ''I copped his clothes, his hat, the shirts. I even took his laugh. Remember that laugh?"

Sometimes an unforgettable performance is a curse. In Weber's photograph, Widmark looks like a character from a Ross MacDonald novel, one of those damned human beings who travel into middle age without ever removing the stain of a youthful crime. Widmark has played cops, Marines, detectives, heroes; but lurking always in the shadows is Tommy Udo, with his manic giggle. In a way, Widmark's entire career has been spent doing time for Tommy Udo.

A great photographer is capable of freezing time and unleashing it, giving us that single decisive moment while allowing all previous ones to exist. I look at Mitchum's great ruined face in Weber's photograph, at the exhausted pouches and wary eyes and the curl of bitterness around the mouth, and he seems a container of a thousand other images. This is the man who tried to break the neck of Gregory Peck in Cape Fear. He has killed a lot of other people too, made love to many women, allowed the softer side of his personality to show less often, in Ryan's Daughter and The Sundowners. I also know something of the man himself: the '48 marijuana bust, the Depression childhood, the long hauls across America when he was still a boy and writing poetry in secret. I've heard through friends the tall tales he makes up with an artist's skill and tells with great conviction. Some people even believe him. All of that is in this picture. Mitchum has come to look like someone you meet hanging around a bus station. That is the image that he invented himself.

A photograph is a fragment of time, often of extraordinary clarity, but the fine photographer always modifies the moment with doubt. In the old glossy studio photographs, there was never any doubt; they said, This is a movie star. But look at Kirk Douglas in Weber's portrait. Yes, he is an actor, and a good one—Paths of Glory, The Bad and the Beautiful—but he is also the son of Herschel Danielovitch, a peddler from Russia, who abandoned his wife and six daughters when Douglas was fourteen. The boy, who was then called Issur, would make it to the gaudy heights of American life, defeating poverty and obscurity; but something in his eyes tells us that after seventy years on the earth he is still capable of fear. That his children have made it is probably the only true way this son of an immigrant has of keeping score.

Obviously, the career of an actor is not a continuous line, and the peaks and valleys are often not his fault; unlike the poet or the painter, he cannot practice his craft alone. Weber forces us to examine Stuart Whitman as perhaps we never have before. There is satisfaction in the face, confirmed by the presence of the cigar. But there are other things too; disappointment might be one of them, because Whitman was often a pilgrim through the wastes of second-rate movies. His attitude says, What the hell. But we also sense that somewhere behind the satisfied mask there is a question: What ip What if a good role had come to him very early? What if he'd found his Kazan or Huston or George Stevens? What if he'd stayed home hungry instead of taking still another movie for the money ? We know he has made many millions with realestate investments; Weber suggests here that perhaps the money was not enough.

All of these men have managed to last a long time, and one possible reason is that we have never truly known them. They possess secrets. Still. They remind us that the great movie actor strips away the mask, but they have not totally stripped away theirs; in each, we see a longing for a newer, more comfortable disguise. All grew up on the dark side of that generation gap caused by the Great Depression. They didn't have to play at poverty; they lived it. It seems as if they often took roles strictly for the money, knowing that what they were doing was perishable junk. But they also remind us that what we get from most actors is a series of feints—they can fake us out of position, but something in them prevents the throwing of the follow-up punch. These men, for all their failures, disappointments, and defeats, went to work prepared to be carried out on their shields.

These men have managed to last a long time, and one possible reason is that we have never truly known them. They possess secrets. Still.

So if there is a peculiar quality of self-mockery about them in these photographs, a certain weariness, they are redeemed by a kind of splendid grace, suffused with the poetry of exhaustion. And if you were to ask them to judge their lives and their careers, they would probably answer with a phrase that applies to all human beings who have made it to the finish line: Guilty, with an explanation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now