Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

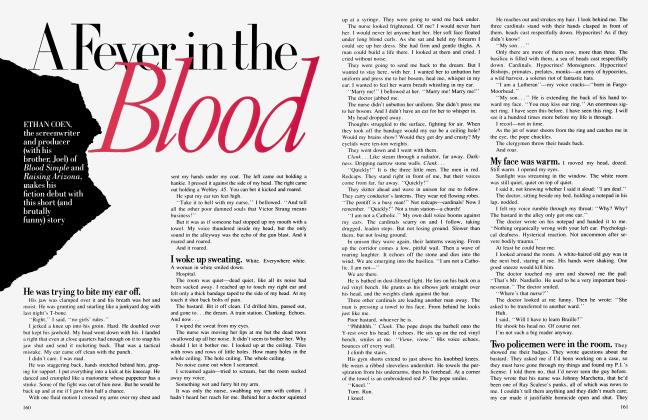

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLionizing Christian

EDMUND WHITE

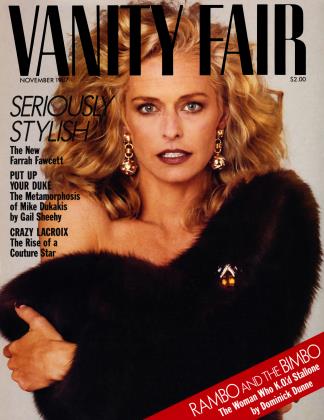

Christian Laconic is now the It Boy of Haute Couture. Not since Yves Saint Laurent seized the fashion thrown twenty-five years ago has there been such a roar of approval. This month Lacroix unveils his ready-to-wear at Bergdorf's. EDMUND WHITE reports from his Parisian salon and la his hideway in Arles. And we emptied the salon to show how it looks without the crush of taffeta

Paris has witnessed this year a triumph of packaging and merchandising worthy of Madison Avenue: the launching of thirty-sixyear-old Christian Lacroix and his new house of haute couture. Not since Yves Saint Laurent emerged twentyfive years ago has such a fuss been made over a fashion tyro. Americans were especially ecstatic after his first show, last July. Hebe Dorsey, clothes critic for the International Herald Tribune, exclaimed, "You can see he loves women!" John Fairchild, publisher of Women's Wear Daily, was wildly enthusiastic, and Kal Ruttenstein, senior vice president of fashion direction at Bloomingdale's, declared, "One of the most brilliant personal statements I've ever seen on the runway." The French press was only slightly more guarded in its exuberance.

Every velvet ribbon and satin bow on this package was selected and tied with fanatical precision. The show started with a salute to Lacroix's native Arles. A slightly dowdy "Queen of Arles" and two blissfully unaffected maids of honor, wearing traditional shawls over long dresses and tiny lace caps, trooped in to a folk song. Then the tempo changed to sassy, the music to a fandango, and the audience, composed of journalists, society leaders, and such luminaries as interior designer Andree Putman, Paloma Picasso ("My father would take us to bullfights in Arles"), and Stella McCartney (Paul's daughter and Lacroix's apprentice), began whooping and applauding nonstop right up to Lacroix's final bow, when he was pelted with flowers like a matador as he stood shyly beside Marie, the young, gray-haired house model, who was in a foaming white wedding skirt, black bolero, and bird-bedecked hat.

Part of the audience Lacroix attracted seemed younger than the usual group at these affairs. This "second-row crowd" was bright, energetic, theatrical, and ready to buy. A lot of them went twice.

I had to see the show a second time in order to take in fully the candy-striped miniskirts, dappled ponyskin kimonos, Provençal prints and pastel minks, winter sombreros and picador caps, tortoiseshell sunglasses suitable for a chic nervous breakdown, gilt brooches patterned after the bullfighters' cross (with anchor and tridents)—it all began to look like the dressing room in a theater where Carmen and The Pirates of Penzance were competing for space. In the delirious atmosphere, boots dripped jet, sleeves dangled mink tails, purses sprouted driftwood-bonsai handles, a wide pink bow cinched in a skirt the color of pistachio sherbet, a model tangoed by with a red silk lunch box in hand while the man beside me rapidly sketched her and the cameras flashed, another model entered sporting a pillbox that had given birth to an enormous black rose. . .The collection was so nutty and feminine that the next day Madonna phoned to make an appointment to see it.

The clothes are not just for pop stars, however. Lacroix's wife of fourteen years, Paris-born Françoise Rosensthiel, with her short auburn hair, mature body, and terrific legs, wears them to perfection. Fran^oise, in the past, helped launch the gift boutique at the Paris Opera house and worked as a designer for Hermes. She has a face as expressive as Giulietta Masina's and a salty, slap-on-the-shoulder humor redolent of the cabaret. But under the hailfellow manner is a sharp, extremely independent, and absorptive intelligence. Neither she nor her husband talks fashion—they both prefer books.

"I loved those early American Technicolor films," he says. "That's even one source of my rather acid colors."

She and Christian have no children, and she wonders if their childlessness hasn't helped them to maintain an adolescent complicity. She does not play a role in his business. As she says, "Perhaps I'm there just to look at things, not to appropriate them. As Godard puts it—to stare off into the air.''

Christian Lacroix is a beaming intellectual who at age four announced he wanted to grow up to be Christian Dior. He is a modest man who can laugh till he cries, but his usual mood is one of gentle reverie and calm precision.

I spent two days with him in and around Arles, visiting the mountain village of Les Baux, Romanesque abbeys, and his cousin's farm. We spent one afternoon in the marvelously restored villa of Lillian and Ted Williams, San Franciscans who, like Lacroix, are obsessed with the eighteenth century. Lacroix praised Lillian's passion for his own favorite period, especially when she showed us her extensive collection of eighteenth-century clothes from Provence. He knelt to examine cloth slippers: "I love this color combination, blue and khaki, so unexpected—and look at this line!" An overcoat reminded him of one his grandmother had worn with an ostrich-feather collar, the body all black ruching.

When I asked him what connection he saw between his designs and American women, he said, "I learned about Paris from American films. I think the distance between a provincial French boy and Paris is the same as that between an American and Paris—for both Paris is a myth that may never have existed but that is real nevertheless." Lacroix has made a hit because of the impertinent, improbable dresses he's invented for that sleek creature who always haunted him when he was a kid: la Parisienne. "I loved those early American Technicolor films," he says.

"That's even one source of my rather acid colors. Another is the look of the forties—Schiaparelli, Balenciaga."

When I mentioned that some people think his clothes look like costumes for operettas, he said, "I'm beginning to design for the stage—I'm talking about doing La Gaiete Parisienne with Baryshnikov." When I reminded him that he'd once confessed he'd never have the "architectural sense" of the designer Azzedine Alaïa, he replied, "I'm more a decorator than an architect, more concerned with mood than structure, and for me mood includes fabrics and accessories." When I mentioned the charge that he's too backward-looking, he said quite simply, "The strength of the future is in the past. That's what gives Japanese designers such power—they've never rejected their traditions."

Continued on page 174

At age four Christian Lacroix announced he wanted to grow up to be Christian Dior.

Continued from page 146

While he was a college student in Montpellier, he specialized in the history of costume as well as in French and Italian painting. He feels that his link to Arles is the one thing that sets him apart from every other couturier, and he is intent on further exploring the connection. "All I have is my origins, the aesthetics of the region, the look of the land and the vegetation." When we visited the house of Louis Jou, a celebrated local printer who died in 1968, Lacroix grabbed an old quilt and pointed out to me the audacious mix of five different fabric designs. His own dresses are enlivened by just such juxtapositions.

And yet, for all his devotion to historic Arles, Lacroix is of two minds about the city. Next year, for instance, Arles will celebrate the centennial of Van Gogh's stay there during the last three years of his life, but Lacroix remarks, "The people had too guilty a conscience to acknowledge Van Gogh until recently. After all, the little boys here threw stones at him. Arles was conquered by the Romans, and it retains a pagan relaxation about sex and a love of public display. When I was a kid, everyone promenaded every evening in their finery. I like to think that my two favorite things, the opera and the corrida, are not too different from the public events that took place here in ancient times. This region is now a stronghold of racism and of the extreme right. But despite these ugly facts, I love Arles, starting with the diversity of the landscape."

After studying art history, Lacroix moved up to Paris and found a job in the public-relations firm of Jean-Jacques Picart. If there is a Svengali behind Lacroix, it's Picart, a bespectacled, preppy man of forty. He is now Lacroix's partner and director of marketing, or, as he puts it, "responsable de l''image." He told me, "Christian and Frangoise were doing P.R. freelance for me ten years ago. I recognized he had talent and found him design jobs for Hermes and Guy Poulin. Then six years ago I persuaded the house of Patou to hire him as chief designer. Christian's first six shows over the first three years were flops. After each flop we'd talk things over, have a dialogue. It's not enough to have talent—you must match it with a fitting goal and an appropriate image. These days people pay not for the product but for the image. My job was to listen for Christian's inner convictions and help him make choices."

In January 1986, while still at Patou, Lacroix won the Golden Thimble, fashion's most coveted award. He and Picart decided to launch their own house instantly. The same corporation that owns Dior promised to bankroll them to the tune of more than $8 million over the next four years. As Lacroix comments, "Of course, the value of the franc has completely changed since then, but it's the exact same figure, 50 million francs, that Marcel Boussac invested in Dior forty years ago."

In keeping with the tone of romantic nostalgia that Lacroix and Picart had zeroed in on, they rented an eighteenth-century town house with an immense garden on the slightly faded Rue Faubourg St. Honoré rather than on the much trendier Place des Victoires. Lacroix's card is charm—that's why the official house color is pink and the interior decoration, by Elisabeth Garouste (wife of the painter) and Mattia Bonetti, is a fresh replay of the whimsical designs of Christian Berard in the 1930s. Black flames lap the enormous white sofas, gold flames in wood flicker over the tripod tables, light shoots out of the eyes of the gilt wall-sconce masks.

Lacroix is surely talented, but the magnitude of his success is also due to the dearth of talent in every field in France. The country, which has the world's most sophisticated and cultured audience for creativity, has been craving a hero. Because of falling exports and the falling dollar, France is in special need of a boost to its luxury trade. French journalists and financiers were eager to jump on any bandwagon that looked likely to budge.

That the focus of national attention should be a dress designer comes as no surprise in a country that has never made a tight distinction between art and fashion— the country where Baudelaire wrote about the Dandy, Mallarme edited a fashion magazine, Dufy designed dress fabrics, and Roland Barthes devoted a scholarly tome to le systeme de la mode.

"Rather sublime" was the cautious judgment of Lacroix's first collection by a fellow couturier (and Arlesien), Louis Feraud. "But the clothes are too rigid. Softness is not his forte. Dresses should be supple if they're to promote harmonious thoughts. Yet the whole collection is intelligent, and ten of the pieces were terrific. We must wait to see how the readyto-wear goes down. Haute couture is a sort of laboratory that works up prototypes that are then adapted to the mass market, which is the ultimate test."

That test will be given in two installments. During the last week of October, Lacroix is promoting not only his couture line but also a luxury line of ready-towear in New York, sponsored by Bergdorf's. His cheaper ready-to-wear will be launched next spring.

Whereas the haute couture prices run high (about $200,000 for a sable coat with embroidered collar and $8,000 for a black lace suit), a luxury ready-to-wear dress adapted from haute couture designs and finished by hand will cost just under $2,000. The basic ready-to-wear, which will give a fantasy twist to a much simpler garment, will cost about $500 a dress.

To succeed, Lacroix must conquer the ready-to-wear market. Although the official estimate is that there are two thousand couture customers in the world, Lacroix estimates that there are only about a thousand. For his luxury ready-to-wear Lacroix has his eye on the Texas market: "Texas women have so many events to go to, especially for charity, and the same women keep seeing each other, so they need many, many new dresses."

Summing up the Lacroix phenomenon, Picart remarks, "It may be a charming style but it's not an easy one. Under the sweetness there is something that bums, that's flamboyant. Like a woman who flirts, then creates a slight resistance— that's the way to make a great passion crystallize." In France even passion is a system, and Descartes rules over Venus.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now