Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPUBLISHING'S NEW RAJA

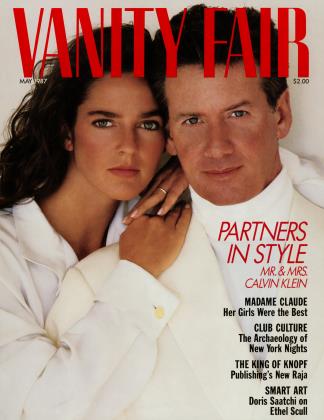

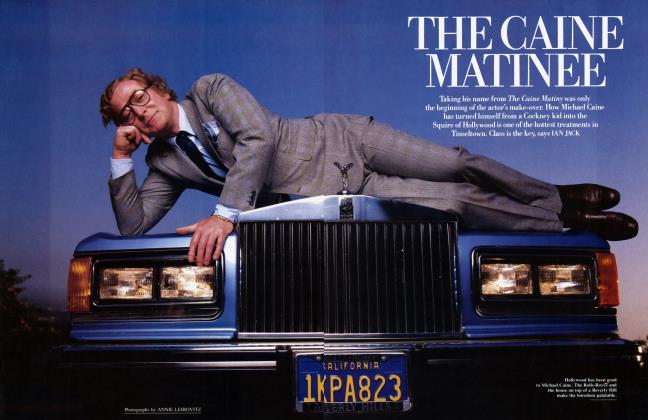

This is the man who's taking over at the house of Knopf, the chair vacated by the new editor ofThe New Yorker. Indian-born, English-educated "Sonny" Mehta is both urban and urbane. In fact, reports IAN JACK, Mehta and his witty wife, Gita, will bring back to literary New York some of the social luster of the original Mr. & Mrs. Alfred A. Knopf

IAN JACK

When Robert Gottlieb, president and editor in chief of the venerable publishing house Alfred A. Knopf, became editor of The New Yorker magazine early this year, he had no doubts about who should have his old job. He proposed only one name, that of Sonny Mehta, who for fourteen years headed the editorial side of Pan Books, Britain's second-largest paperback company. But why entrust the future of one of the most famous publishing imprints in America to a forty-four-year-old Indian citizen with very little experience of finding and publishing hardcover books, and no experience of selling in U.S. markets?

To the unsuccessful candidates for the Knopf job—and several well-known names were bandied about town as contenders before Mehta's appointment was announced— this may seem like a reasonable question, although Gottlieb finds it parochial. "Sonny has a very high international standing," he says. "Also, he's a very good person." And in New York, or at any rate the parts of it that care about such things, knowledgeable heads nodded in sage agreement. Newspapers and magazines were full of quotes from publishers and agents describing Mehta variously as "eclectic," "shrewd," "brilliant," and "humorous."

Mehta himself did not immediately throw his hat in the air. A few days after accepting the job, he was sitting in his London office confessing to a feeling of "primal fear." Talk of his brilliance made him nervous. "I mean, just why the fuck do they think I'm brilliant?" He thought he was about to discover "whether I'm any good at all.''

The Mehtas are products of the steady Westernization of the Indian elite.

The book-buying public usually pays little attention to the publishers of the books it buys, but in this case Mehta was getting the fallout from interest focused on the shift of Gottlieb to The New Yorker, which fed the gossip mills of literate America for weeks, and it made him feel anxious. Some of this anxiety may have been manufactured, a relic of the stumble-and-mumble Jack Nicholson days of the late 1960s, when self-confidence was always decently cloaked in self-doubt. Superficially, there is a lot about Mehta to suggest this period. The first thing that strikes strangers about him is that he comes not so much from a country, India, as an international time zone where the clocks stopped in 1968. He wears sneakers and jeans, his conversation is laconic and decorated with period features ("kind of...sort of'') and the occasional Americanism ("sonofabitch''). The enthusiasms of the 1970s, jogging and rural pursuits, have not impinged on the way he lives. He describes himself as a sybarite. His idea of outdoor activity is watching an international cricket match, preferably played between England and India. His idea of indoor activity is cards and backgammon, preferably played for money. He smokes hard and he pours stiff drinks; he likes to give parties; the idea of that great English treat, the country weekend, fills him with dread ("I'd always be worrying: how do we get back?"). Neither he nor his wife drives. They are at home in taxis and restaurants, flicking cigarette lighters and keeping yawning waiters from a good night's sleep. A friend who has known him for twenty-five years, since they were both students at Cambridge University, remembers him for his "enormous languor." "He was capable of spending an entire weekend in bed or an entire day in the bath, with his toe on the hot tap to turn up the heat." "Laid-back" is a word that, sooner or later, is bound to crop up in any conversation about him. "Reptilian" is another; several friends compared him to a lizard, asleep and yet not asleep on a rock.

Few think that his air of self-containment and self-concealment is affected. Richard Eyre, the director-designate of Britain's National Theatre and one of Mehta's most enduring friends, says of him, "It's true that he can seem almost willfully enigmatic at times, but it's just the way he is, and it would be quite wrong to construe his quietness as a brilliant stratagem of corporate behavior." In any case, the laid-backness is totally misleading as a key to his success as a publisher, a man who in the judgment of his peers and rivals is an inspired finder and seller of books. Lynn Nesbit, the New York agent, thinks he has "the instincts and psychology of a good agent.... He's at all these parties and lunches assessing the personalities of the people he's dealing with. He understands the parameters. He understands where the deal will end."

New York, in the strictly professional sense, should contain little to frighten Mehta. He spent a month or two every year there after he took over as editorial director at Pan, and knows it well. He is admired by those with whom he does business as one of the most formidable publishers to emerge in Britain in the fifty years since Allen Lane devised Penguin Books and gave quality and intelligence to a form of publishing that had previously been noted only for cheapness and disposability—the paperback. Penguin is still Britain's largest paperback house, but Pan has in recent years stolen Penguin's reputation for the new, original, and interesting; the book of the moment. The distinguishing feature of both Knopf and Pan is their ability to find and market "literary" as well as "mass appeal" books, though these are categories which Mehta acknowledges only with reluctance.

Mehta insists on being self-effacing about his reputation. "I think the difficulty with publishing is to know precisely how one has contributed to the success of a book. The director of a film or an opera knows what he's given to the production. The truth is that I've never known quite what I've contributed." Such diffidence is a trait his English friends worry about. They fear that New York might damage a personality that is sustained by privacy, and contort a charm that cannot be produced on demand, for everybody. Sometimes the diffidence even amounts to rudeness, and sometimes it ceases to be diffidence altogether and becomes pure depression. Colleagues recall days at Pan when Mehta would sit grim and silent in his office for hours at a time, until his blackness percolated through the entire building. Then his staff would refer to him as the Ayatollah, and wonder, individually, what they had said or done to upset him. "You needed to be fairly convinced of his genius to work for him," says one of his former editors. "He was a rotten administrator, and there were days when nothing at all would happen other than Sonny sitting behind his desk and pulling a metaphorical blanket over his head."

The blanket seemed to be descending as we left the office to visit his apartment. When we arrived, his wife, Gita, who lay ill in the bedroom, called through the door: "I hope you're telling him some jokes, Sonny." But by that time Mehta was trying to devise ways of not talking at all. "I'm just not a very interesting person," he said.

Gita came into the room and patted his hand playfully. "Oh, you're quite interesting, Sonny." She turned.' "He plays a good hand of gin rummy, you know."

Sonny and Gita, Alfred and Blanche. People who remember the original Mr. and Mrs. Knopf say that the Mehtas may restore something of that couple's social luster to the publishing house that still bears their name. And then people withdraw the comparison, remembering that Blanche and Alfred did not have the most harmonious marriage. Sonny and Gita have been married happily, if sometimes rambunctiously, for more than twenty years (Sonny can't remember the exact date) and have a son, Aditya, who is studying mathematics at the University of Edinburgh. They have often been apart—she in New Delhi, he in New York—but when they are together they form a partnership that reminds people like me (who cannot remember the Knopfs) of brittle cartoons in The New Yorker. Theiidomestic life has always been more Manhattan than London. While most publishers live in houses in the northern and western suburbs among tight circles of friends— other publishers, agents, sometimes authors—the Mehtas lived in and still retain a duplex apartment centrally placed between Hyde Park and Victoria Station. While other publishers gave dinners with a guest list that seemed fashioned from a monocultural monosodium glutamate, English and white, the Mehtas threw parties at which it was possible to meet, say, the Rajmata of Jaipur, or Imran Khan, cricket captain of Pakistan, or Bruce Oldfield, the fashion designer, as well as a gamut of authors that on a good night could run to Salman Rushdie, Bruce Chatwin, Germaine Greer, Michael Herr, Ryszard Kapuscinski, Clive James.

Sonny listens to his guests, Gita talks to them. This social dynamic has operated ever since they met as fellow Indians at Cambridge in the early 1960s. Clive James, then fresh from Australia, remembers them there as "the most beautiful couple I'd ever seen.. .Gita said a lot, and all of it was funny; Sonny didn't say much, but what he said was good.'' Gita's wit is well demonstrated in Karma Cola, a book that originated, as some books tend to do, at a Manhattan cocktail party. Marc Jaffe, then head of Bantam Books, introduced a fellow guest to Gita with the words "Here's the girl who can tell you all about karma."

Gita: "Oh, karma's not all it's cracked up to be."

Jaffe: "Hey, that's a great idea for a book!"

Gita wrote with amazing speed, and the result, a vivid description of hippiedom's blundering encounters with what it perceived as Indian mysticism, was well received in America (English critics, including Angus Wilson and Jonathan Raban, thought it too smart-assed for its own good).

The Mehtas are themselves the products of an older and more significant East-West encounter. Not the vain, brief Orientophilia of Western youth in the 1960s, but the slow and steady Westernization of the Indian elite. The origins of Sonny's keen publishing instincts lie somewhere in this hybrid culture, though here we tread the tricky ground of cause and effect in the human personality. All we can do is take Sonny's word for it. "My responses," he says, "are Indian."

To one of Gita's hippies, "Indian" might mean karma and dharma, fate and duty, and a bit of spiritual hash and splash in the river Ganges. Sonny is not obviously Indian in that sense, nor in the sense of a close and rooted family life. He was bom Ajai Singh Mehta into a family of well-to-do Sikhs in New Delhi in November 1942. His father, then an officer with the Royal Indian Air Force, later joined the Indian foreign service to become one of the newly independent country's first diplomats. Posted abroad, he abandoned the badges of Sikh orthodoxy, uncut hair and a turban, and in doing so relieved his son of the need to wear coiled pigtails (Sonny remembers this with gratitude, though he still wears the Sikh kara, an iron bangle on the wrist). By the time he was eight, Mehta Jr. had lived in Prague and New York and acquired his enduring nickname, Sonny, from an American neighbor.

He went to an Indian boarding school at the age of ten, when his father was posted to Nepal, then a primitive and barely accessible part of the world, and, vacations aside, has rarely stayed with his parents since. The school they chose for him was Sanawar, originally a Victorian establishment for the British military which puts in an appearance in Kipling's Kim: "We'll make a man of you at Sanawar—even at the price o' making you a Protestant." On foothills all along the fringes of the Himalayas stood similar schools. Gita, the daughter of a political boss in eastern India, went to one only a few miles up the valley from Sonny's; Rajiv Gandhi to another farther down the slopes to the east. In all of them—in fact in every reputable Indian school—books meant English books, and literature, English literature. Children stood up in class to recite Shakespeare and Wordsworth, and settled down at night with Jane Austen and Dickens. The divisions between the foreign and the indigenous became blurred; the idea that literature had boundaries, like nation-states, made no sense.

This may be the seedbed for what his fellow publishers call Mehta's "international feel" for books, but his "eclecticism," another word which haunts him, comes from somewhere else. On the streets of every Indian city, booksellers spread their wares across the pavement, occasionally slapping volumes together to shake off the dust and attract the attention of the passerby. Every conceivable kind of book is there—Plato's Republic, old chemistry texts, the new Patricia Highsmith. Gita swears she has heard one old huckster in Delhi thump a Penguin edition of the Odyssey and cry out, "Sir, sir, Homer has come."

Sonny was hungry for new books and new sensations. "Eclecticism was part of growing up in India," says Gita. "It has something to do with greed." Sonny bought books and more books—thrillers, romances, Tolstoy, Damon Runyon—simply because they seemed to him, in a country with few other sources of entertainment, "the cheapest and most natural form of recreation.'' He caused wonder among his fellow students at Cambridge, where he won a scholarship to study English and history. Richard Eyre says, "He seemed to have an education the rest of us didn't possess. It was as though he'd been equipped with the sensibilities of a New York Review of Books reader at the age of only eighteen or nineteen." Two other qualities that later served him well also became visible. He had a massive appetite for junk reading and a twitching antenna for shifts in popular taste, in films and music as well as books. In Eyre's words, "He always knew what was going to be hot."

Continued on page 133

Continued from page 87

After Cambridge, Mehta tried, rather halfheartedly, to follow Indian convention and his father's diplomatic career, but he overslept for a crucial examination and scored too low to be offered a place in the foreign service. Publishing seemed the obvious choice. He loved books, and yet had no inclination to write them. But English publishing did not throw open its doors to an Indian. Mehta watched with surprise, and some hurt, the effect his skin color had on the men who agreed to see him. They would raise their voices and slow their speech, the better to make themselves understood, and then express polite astonishment that Mehta spoke excellent English. A feeling of separateness was added to his self-containment.

Eventually he found a job with a small hardback house, Rupert HartDa vis, which soon after was taken over by a publishing-and-television conglomerate. The conglomerate wanted to start a quality-paperback imprint that would serve and stimulate the new interest in popular sociology. They gave it a name, Paladin, and put Mehta in charge of the list. Casting around for titles, he took his friend Germaine Greer to lunch. Various ideas were batted back and forth over the table, all of them books for other people to write. Greer thought of her career in terms of academic life. Then Mehta suggested that something could be done with the fact that the fiftieth anniversary of female suffrage in England was being celebrated. Greer says that she "ranted on and on" about the unfulfilled aspirations of women.

Mehta said: "That's the book I want." Greer said: "Oh, Sonny, I'm a university teacher.. .the world's full of bad books by university teachers." Mehta said: "I'll draw up a contract and you can sign it in the afternoon."

Greer got an advance of £750 (about $1,800). It was, of course, a brilliant notion, which Greer is happy to acknowledge as Mehta's, though she says that The Female Eunuch's commercial success owes less to him than is commonly supposed. It took off, in her view, only when McGraw-Hill bought it for America and pumped cash into its marketing and publicity. If so, it was a lesson Mehta took to heart.

Two years later, in 1973, Mehta was made Pan's editorial director. Ralph Vemon-Hunt, the man who hired him, noticed two striking features of his style. One, he wore exotic clothes around the office—sandals, tight Indian pajama trousers, loose Indian shirts. Two, he got on well with the salesmen. "They all liked him. When I came into publishing, just after the war, if you were a salesman you got a sandwich for lunch at the back door. But Sonny knew it was no good just publishing books, they had to be sold, and the first people you had to enthuse about them were the people inside the company."

This raises a fundamental question about Mehta. Nobody denies his immense strengths as a purveyor of books, but how good is he as an editor, someone who can sustain an author's confidence and improve his work? An editor who has worked with Mehta says he hardly edits at all: "He may offer advice about structure and tone of voice, but I've yet to see him with a blue pencil, poring over a manuscript." Others have had a different experience. Salman Rushdie says that Mehta "pays a most remarkable attention to detail— his eye is really quite extraordinary." Last year they worked together on Rushdie's Nicaragua book, The Jaguar Smile, for several days. "There's no doubt that Sonny substantially improved it." Mehta is happy to receive such plaudits, but he has no illusions about himself as the new Maxwell Perkins, the New York editor who could tease great books from the unpromising woolly jumble of an author's first draft. He knows the legend, but it doesn't interest him. "There are editors who believe that working with the author on his manuscript is their chief, almost exclusive function. I don't see that. I believe that finally it's the writer who writes the book."

According to Michael Herr, Mehta "knows how messy it is to write a book, but he's not a failed writer. He puts the same kind of energy into publishing as writers do into writing." It was Herr's account of the Vietnam War, Dispatches, that marked a turning point in Mehta's career. He had published popular American fiction at Pan with great success, but Dispatches was journalism by an unknown author about a war that had not involved Britain and that most publishers assumed the public wanted to forget; worse, there was no film tie-in. Mehta put it out under the Picador imprint and in the nine years since, it has sold nearly a quarter of a million copies, much to the amazement of its author. In other words—and taking the much smaller size of the British market into consideration—Dispatches had done better in Britain than in the U.S., whose war it attempted to describe. How did Mehta achieve this? There are quantifiable factors; it is not just "instinct." First, he extracted a testimonial from John le Carre and splashed it on the cover: The best book I have ever read on men and war in our time. Second, he pushed a somewhat shy and anxious author into radio and television studios.

The trick bore repetition. In the years since, Mehta has published a whole series of American books that other London publishers considered too problematic for an English audience, or that had been published by them to stunning public indifference. Mehta took them on and got them talked about and widely reviewed. He thinks this is his most satisfying publishing achievement. "The hardcover-publishing process was totally bypassed. We've used paperbacks as the launchpad for a lot of good and controversial new American writing."

As a list of minor cults, it is impressive: Maxine Hong Kingston, Bret Easton Ellis, Edmund White, Tama Janowitz, Spalding Gray. He has got their publicity right and their covers right, judging (accurately, as it turns out) that Britain has an appetite for the present as well as the past, and that the American present is more desirable than the British one, or at least better evoked in books. "Fiction at its best," he says, "should deal with what's happening now." He has no qualms about shoving Tama Janowitz on rock-video shows or persuading Spalding Gray to make stand-up tours of provincial theaters. The result is that both the Picador imprint and Mehta himself have acquired a reputation for calculated trendiness, which has sometimes obscured the more solid qualities in the list and in the man.

Some people expect large things of Sonny Mehta. For example, Gary Fisketjon, the thirty-two-year-old editor in chief of the Atlantic Monthly Press, thinks that American publishing has seen nobody like Mehta, unless it is Gary Fisketjon. He happily acknowledges that he has stolen many of Mehta's publishing techniques—"I've ripped him off as much as I could possibly rip him off"—and he thinks his arrival is "great news for an industry stagnated beyond belief, where so much publishing seems designed to promote mass disinterest." People like Mehta and Fisketjon, says Fisketjon, realize that books are part of the entertainment business.

But Roger Straus, of Knopf's rival, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, has a more modest assessment of the changes Mehta might bring. "I think he'll take some gambles on certain kinds of books because he has offbeat tastes that Gottlieb doesn't share. And I think that, unlike Gottlieb, he won't be eating a lonely sandwich on his lunch hour. He'll be zipping around town and stirring up the elves a little bit."

In any case, an old response will have to be rewritten. On Mehta's frequent visits to New York over the past fourteen years, strangers have often asked him if he is any relation to Zubin Mehta, the conductor, or Ved Mehta, the New Yorker writer. "No," he was apt to reply. "I'm the other Mehta, the untalented one."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now