Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPRESSING GRAPES

Whir

Importers like Ab Simon apply muscle to wine prices

BY JOEL L. FLEISHMAN

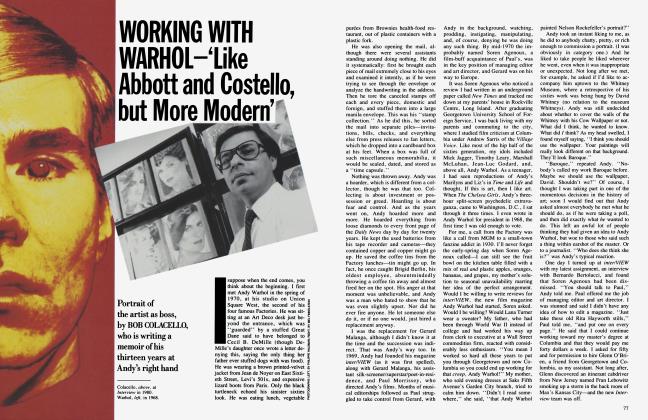

A legion of middlemen —brokers, negotiants, exporters, importers, wholesalers, retailers, and restaurant owners—stand between grape growers and the people who drink wine, and all of them have some say about which wines we will be able to buy and how much we will have to pay for them. But among the many players in the international fine-wine game, none is more influential in setting prices than the large importer, for his purchases are in the thousands of cases. His marketing and advertising schemes create and sustain the demand for particular wines, and with his network of sales personnel he persuades restaurants and retailers to purchase his wares.

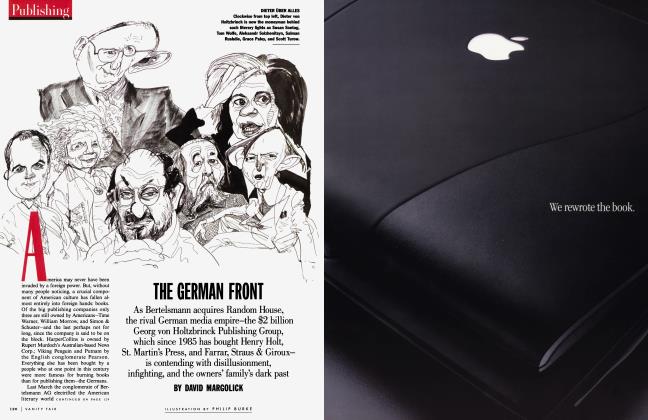

The most powerful importer in the world of quality wines for the last dozen or so years has been a charming, multilingual American, Abdallah H. Simon, an Iraqi Jew with a first name which is thought by some to mean that he is an Arab but which is in fact of Turkish derivation. The company that Edgar Bronfman recruited him to head in 1974, Seagram Chateau & Estate Wines, has become the largest purveyor of fine wines in the world, with gross annual sales of over $60 million. Under Simon's guidance, Chateau & Estate jumped from 45,000 cases of imported wines in 1974 to 900,000 cases in 1986. Simon is the world's largest single buyer of the top Bordeaux chateaux. C. & E. is also the exclusive importer of Perrier-Jouet champagne, which Simon lifted from 100 cases in 1974 to 70,000 cases in 1986, making it the fourth-largest-selling champagne in the U.S. And the firm imports 60,000 cases a year of MaconLugny Les Charmes, which makes it the largest-selling estate-bottled Burgundy, white or red, in this country.

No wonder that when Ab Simon speaks, wine producers listen. Last November, the front page of the New York Times business section carried a headline proclaiming, BURGUNDY PRICES FALL SHARPLY. Three paragraphs from

the end of the story, the reader discovered that a month before the annual Hospice de Beaune auction, Ab Simon— together with another importer, Peter Sichel—had told sixty Burgundy producers that their prices were too high for the U.S. market, which consumes 33 percent of Burgundy's total case output. Both Burgundy growers and Bordeauxchateau owners had grown accustomed to prices that seemed always to go up, or at least remain the same, but never to go down, at any rate for the past five years. But those were years of a strong dollar and a weak French franc. Now things had to change. If, for example, Bordeaux prices in francs for the 1986 vintage remained the same as those for the 1985, American consumers would have to pay 50 percent more for the 1986 wines than they had for wines three years earlier—solely because of the currency reversal. The same would be true for most other French wines, including Burgundies.

In his warning to the Burgundians, Simon gave them twelve years' worth of evidence for what we hereby dub Simon's Law. Stable wine prices, he discovered, produce sustained sales

growth; price increases invariably lead to sharp declines. When prices remained stable for three years, from 1974 to 1977, Burgundy sales zoomed 200 percent in the U.S. When prices doubled in 1980, sales declined 45 percent. And the same pattern repeated itself twice more up to 1986. In other words, unless the Burgundians lowered prices, he warned, there would be a sales decline in the 1986 vintage of about 30 percent. The vintners listened, and prices were lowered by up to 50 percent from 1985 levels.

In a December letter to the chateau owners of Bordeaux, Simon made the same point again. He urged a 15 percent reduction on the first growths, and a 30 percent reduction on everything else, and he got two-thirds of what he asked.

If one believes the universal testimony, Simon's effectiveness derives not so much from his considerable market power as from the extraordinary personal regard in which he is held. In his thirty-five years in the wine business, his integrity, warmth, and loyalty have garnered a host of friends. "The wine business," he says, "is a nice business, full of nice people." Perhaps Simon is a bit overgenerous, but when one is as charismatic as he is, one has the luxury of ordering one's life and business dealings so as to deal only with "nice people." Relationships with Simon seem to be essentially personal in nature, built up over the years, relationships that support and facilitate the transaction of business for long-term mutual profit. For instance, when the 1980 vintage came along—a year of light wines compared with the two preceding vintages—other importers did not rush to buy. But Ab Simon bought just as if it were a great year. "They were good wines at bargain prices," he explains. Lo and behold, it was those purchases made in 1980 which became the allocation ceilings for the much-sought-after great vintages right up to the present. Calculation? Luck? No, long-run relationship! "Take the lesser wines with the great ones," Simon urges. "That's good business. That's marriage. That's life."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now