Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

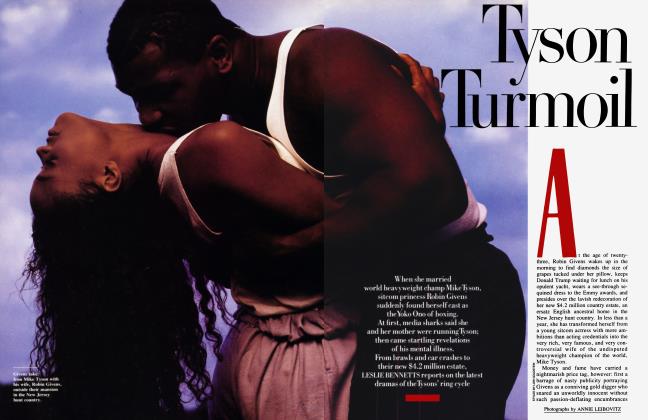

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowANOUSKA WHO?

Fashion

The bright new spark of London fashion is Lady Weinberg, a.k.a. Anouska Hempel

GEORGINA HOWELL

If you're wearing a hat, hold on to it. Anouska Hempel, who started her "ready-to-wear couture" business two years ago, may look like the Little Match Girl, but anyone in the vicinity of this waifish Australian blonde is swept along in a force field of her imperatives. She's past you and up the stairs before you have time to take off your coat. "I'm on a high energy level at the moment," she calls back over her shoulder. "The trouble is, my metabolism can't catch up."

Venetian mirrors reflect a blur of red silk cloque above twinkling black pumps with scarlet rosettes as she nips along the gray corridors of Blakes (the extraordinary hotel in London's South Kensington that she also runs), pursued by a housekeeper, a majordomo with a sheaf of lists, and myself, her metabolism stumbling along in the rear.

Practically the only bright spot in this year's London fashion shows, her collection brought excited ovations and a chorus of "Who is Anouska Hempel?" Her stamp as a designer is extreme formality combined with stylization derived from strong technique. In her black-and-dark-blue shop in Pond Place, billowing with operatic drapery, the strict tailoring of her chic little suits rustles shoulder to shoulder with her evening dresses: khaki satin and black velvet, lipstick-red silk, draped sheaths with surrealistic wings and volume, bells of black lace, tables of canotiers with black ribbons, velvet, veiling, and Ascot cartwheels. You can buy them at Barneys New York, Jimmy's in Brooklyn, Claire Pearone in Ann Arbor, and Maxfield in Los Angeles. They are sexy, predatory, grand, and cost between $2,000 and $10,000.

She designs the clothes, she says, for the fun and glory but "more importantly for the sake of doing something really well." Followed by an assistant taking dictation on the run, she leaps from her black Mercedes holding a bottle of pink champagne for the workroom and scoots through the shop and upstairs to introduce some of the "wonderful interna-

tional hands that make it all possible"— from Diisseldorf, Tokyo, Paris, Poland, Greece, and Brazil—under the supervision of premier Roy Allen, who was apprenticed to the tailoring trade at fifteen and spent twenty-five years with Queen Elizabeth's dressmaker Hardy Amies. With hundreds of dresses on order, there are two workrooms in full swing, plus Anouska Hempel's private studio across the road from Blakes. But still the Croc-

odile Dundee of the clothing business doesn't express herself in fashionspeak.

"You can change the shape of a woman in a second. It's all built into my dresses with good old gardening wire, all wrapped up in green piping," she says. And "I don't give a hoot about the subliminal message: I give them strict tailoring with a little bit of nonsense for day, and for evening I give them dresses that push up the boobs, pull in the tummy, and banish the bum!"

After only a handful of collections, half of her market is in the U.S., and she boasts such customers as the Princess of Wales, Ann Getty, Ali MacGraw, Carol Price (wife of the U.S. ambassador in London), and a group of Rothschilds.

The dress business is the latest, and probably not the last, division of the style empire that she began twelve years ago when she and her first husband bought a down-at-heel rooming house and turned it into the $50 million hotel it is today. In 1980 she married the widower Sir Mark Weinberg, chairman of the Allied Dunbar insurance giant; their combined family extends to six children. For three years she stayed at home to get them settled and then, in a burst of pent-up creative energy, established the fashion house.

"Housekeeping check," she calls, doing her Leona Helmsley number, tapping on a door at Blakes. She bends double to peer through the keyhole, then turns the key. A rush of lavender and potpourri sweetens the air. We step inside an Indian palace. Behind a cascade of swagged curtains (a Hempel hallmark), fine sudare blinds with gray silk frogging and tassels cast slatted shadows across a maharaja's gilded bed and thronelike chairs made from elephant howdahs. The bed frieze is repeated in gold stenciling on the walls. A beatenbrass tub chock-full of cut mauve flowers shimmers on a table hidden in rich drapery.

Anouska Hempel stops dead. "This is the wrong bedspread. Why? You should have three spares for each room and this should be gray. See to it. What on earth are those mirrors stuck way up there for? They're supposed to be level with the bedside tables. Ring for Lenny. Tell him I'll kill him if he's made a mark on the silk."

By the time she started the hotel she had already worked through four other careers. As an actress she kept hearing what other international actors wanted: a place to stay when filming which wasn't like a hotel. "After that I just decorated each room as though I was going to live in it myself."

Faye Dunaway likes the black suite with its two black-and-gold four-posters and the window bars, because she has a thing about security. Rupert Everett moved into the Gipsy Room with its black Portuguese bed and armoire exuberantly inlaid with mother-of-pearl, and stayed a year. Bianca Jagger likes the Jade Room with the botanical prints, Nastassja Kinski the Madison with twenty-three Kipps views of English country houses and parks. Issey Miyake liked the Indian gilded bed, but put the cushions and bedspread in a closet to simplify his room. Even the chamhres de bonnes in the attic, starting as low as $175 a night, are formal, intimate, and unique. In the reception area, where Shanghai Express meets Key Largo with lacquer and birdcages, seagoing trunks and an old black telephone, visitors may pass Mickey Rourke, Princess Pignatelli, or the Aga Khan on the bamboo stairs. In spite of the strong sense of theater, there is nothing stagy in Anouska Hempel's decor, or in her couture.

"I'm an engineer and builder and architect at heart, and everything I do has to be secure and perfect first. The quality on the inside of my clothes is exactly the same as the quality on the outside. A room in the hotel is done to the same standard as my own house."

They are rooms and clothes for duchesses—and Lady Weinberg dines with a few. But comparisons to other social figures turned designers, such as Carolina Herrera or Jacqueline de Ribes, are wide of the mark. A closer London parallel might be Lady Tryon, the Australian wife of a banker baron, and a confidante of Prince Charles's. Dale Tryon's warmth and candor won her a prime place in London drawing rooms and shooting circles before she astonished her friends by bringing out a line of dresses.

Dale Tryon, however, came from crusty Toorak in Victoria and grew up in green gardens beside swimming pools, skied and sailed and went to a finishing school. Back up from that several lightyears and you'll begin to grasp Anouska's origins. Forbes, on the way to Broken Hill, is four hundred miles west of Sydney. "I'll tell you what it was like," says Anouska. "Flies, sheep, dust, dirt, sand, gum trees, burs, snakes, and spiders. You had to be strong. You never cried."

Her mother is Russian, from St. Petersburg—"An aristocrat? That'd make her laugh." Arriving in Australia via the cotton fields of Shanghai, she met and married a wheeling-and-dealing German farmer from South Africa. Anouska Geissler was the eldest of their three daughters. "All we ever saw outside the family were an Irishman and two farm laborers on the station. And, once a month, the Flying Doctor, who brought the correspondence courses we children were supposed to do." Her mother sent for McCall's patterns, and between jobs the girls quite literally cut up curtains to make frocks.

At seventeen Anouska sailed for England with one sister in tow, £10 in her pocket, and one coat between them. "We had no idea anywhere could be so cold." Out of money in two days, the seventeen-year-old pounded the pavements in the coat, trying to find work, while her sister stayed in bed. Finally she went into a bank, demanded to see the manager, and borrowed £100 on the strength of a fantastic story about her father being a millionaire. She went to the London Accommodation Bureau to find a room and came away with a job.

A few years later, when she was dealing in property, running an antiques stall, and acting in commercials and films, she married Constantine Hempel, a Reuters journalist. Then he was killed in a car crash. After that she concentrated entirely on their two children and the shabby rooming house they had invested all their money in. Room by room, she set about restoring, renovating, decorating. She was receptionist, cleaner, window washer, and she began to exploit her talent for attracting a devoted core of staff. "It's easy. If you're motivated enough yourself, you can motivate others. Motivate enough people and you can get anything done."

For some years after her husband died she refused to contemplate other relationships, but in 1980, she married a neighbor, the distinguished South African lawyer and financier Sir Mark Weinberg, whom she'd first encountered at a residents' meeting about whether their road should be used as a bus route. "He got his points over quite brilliantly," she remembers. "I was emotional, volatile, didn't get my facts straight, and he laughed at me."

Today she entertains for him with dazzle and eccentricity, plays the corporate wife to the hilt, most recently at a convention in the Seychelles, and has installed the extended family—including their six-year-old son—in quite shatteringly elegant surroundings of dark-green Venetian Empire. "Mark says it's uncomfortable," she reflects. "I wouldn't know," she adds naughtily. "I'm hardly ever there."

Time together is spent in their weekend home, an old moated house in Wiltshire. Even there she can't be stopped for long. She has already established a conservatory and a vegetable garden.

She is fierce about her independence. "The profit from Blakes finances the fashion. Now and again I have to ask Mark's advice on tax structure. I'd be stupid not to, but it nearly kills me."

She's an individualist who puts her own strong stamp on everything around her. Even when the Weinbergs go on holiday they take their own linen and silver, stacked into Vuitton trunks, and on arrival at the borrowed villa she'll reorganize the house from roof to cellar. At present she's battling to bring herself down from a U.S. size 6 to size 4, so she can save time by wearing model samples from the shop.

Does everything have to be exactly right? I ask her. Does she work out every morning? Does she go in for facelifts and energy diets?

"D'you think I'd look like this if I did?"

In her late thirties, she looks very pretty, but tired. Only her husband, say her staff, can exercise a calming effect. The academic and financial wizard, seldom off some government body or think tank, keeps a close eye on his wife and manages to ground her effectively from time to time. Once recently she was incensed because her staff had substituted basil for the mint leaves with which her guests were meant to conclude the meal by wrapping them around chocolate beans.

"Life's too short to get steamed up about details," he told her across the table. "Anouska—this is only a dinner party."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now