Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE FAST LANE AT HOME

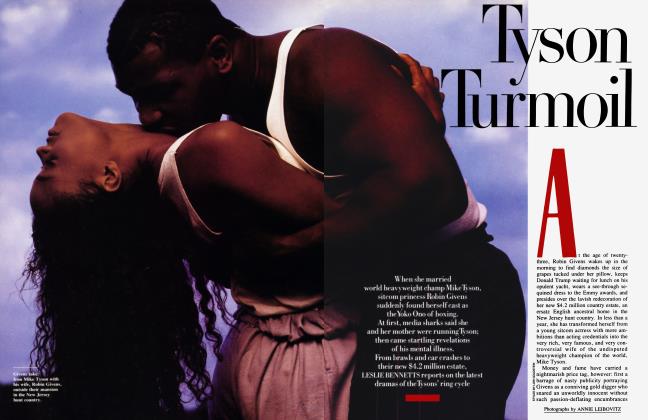

Kenneth Jay Lane, the man who made costume jewelry indispensable on the best throats and wrists, thinks of his Park Avenue home as a tent. GITA MEHTA opens the flap and takes a look around

GITA MEHTA

The first time I visited Kenneth Jay Lane at home, it was for lunch. Not one of Mr. Lane's large luncheons but an intimate affair for three in a dark Manhattan town house with crystal balls glowing on every table. The crystal balls were redundant. Kenneth Lane was already the man who had made it more fashionable to wear costume jewelry than the real thing, burying forever the era when only women with fabulous wealth, such as the Cunard ladies, had the courage to wear junk jewelry, daring to grind their emeraids down to look like glass beads.

The elegant Mr. Lane's real glass beads are a sign of distinction, sold in his shops in London, Paris, New York, and Los Angeles, and worn by women whose names are synonymous with glamour—Jackie Onassis, Princess Margaret, Nancy Reagan, Audrey Hepburn, Elizabeth Taylor—a success that owes much to the designer's sense of fun.

Twenty years later, Kenneth Jay Lane is still having fun. The dark town house has been exchanged for vaulted rooms with moldings you could drape around your shoulders and get married in, so hoch the baroque. "I had them specially commissioned. They're made of soap."

Instead of crystal balls and chandeliers, huge billiard-table lights add additional glow to a Sister Parish lunching here, an Earl of Warwick there. Nina Hyde, textile expert, sits on the leopardskin. Galanos, creator of First Lady outfits to K.O. the Kremlin, puts his drink down on the table covered with village sarongs. Dazzling urbanites, who would get agoraphobia if they had to step off the curb farther than it takes to get into a limo, discuss the shortage of men in Manhattan in front of a painting of Bedouins staring into a horizon of sand dunes while the Rajmata of Jaipur chats with her goddaughter Cornelia Guest under a picture of an Indian water carrier propped up on an overflowing bookshelf.

'When I left my last house I got rid of everything. Then I started collecting again.

"I had the moldings specially commissioned. They're made of soap."

"Why all these things from the East, from Arabia?"

"I must have read The Wilder Shores of Love when I was too young. Actually, I like the East because it's slightly less serious than the West. I also spend a lot of time listening to Barbara Cartland singing 'The Desert Song.' Here, let me play it for you."

He disappears up the stairs onto a minstrel's gallery crowded with books, and Barbara Cartland's genteel warble oozes over the balustrade. "It's not just the East. I've always collected things. When I was a small boy I had an uncle who used to throw arrowheads around in the dust so I could collect them."

"How did you get into baubles, bangles, and beads?"

"Shoes. I was designing shoes for a Scaasi collection. We made jewelry to match the rhinestone shoe ornaments, and I thought a collection of costume jewelry would be fun. So I ended up doing one, because I wanted to see it. That's my song: 'Show me!' "

His pleasure at being shown has made him that rare thing, a man of the world who isn't bored. Delight and erudition shine through his descriptions of forgotten churches built by Venetian merchants on islands in the Adriatic Sea; the Moroccan cavalry in flowing white garments guarding the palace of the king; movie stars strutting their stuff at Irving Lazar's parties in Hollywood for the Academy Awards.

"Are you a native New Yorker?"

"No. I'm from north of the border. Detroit."

The desert paintings begin to make sense. What else would you dream of, in a north-of-the-border winter?

"And my mother was the very first lady U.S. marshal."

I die for Mom. "Did she have a star and six-guns and all?" His laughter turns into a Doc Holliday cough. We both light cigarettes for a breather.

"When I left my last house I got rid of everything. Then I started collecting again. I always think of myself as living in a tent."

Some tent. And yet the nomad's restlessness is visible in the objects, pictures, magazines, and books filling his apartment, which display not just a collector's passion but an endless curiosity about the world. Those who have had the misfortune to be abroad with Mr. Lane know just how endless that curiosity can be, as they journey in ancient taxis to places without addresses so that he can spend happy hours chatting with craftsmen, before he finally exclaims, "Great Quality!" and buys something.

(Continued on page 220)

(Continued from page 163)

Or engage in the endurance test required to reach the ruins of some past civilization which he, oblivious of the discomfort and without a crease in his Savile Row suit, surveys at length before pronouncing, "Great Quality!"

Despite the Anglophilia suggested in his attire, it's the enthusiasm lacking in ennui which proclaims Kenneth Lane an American dandy. Contemporary European dandies are inhibited by the weight of a Proust or a Beau Brummell, but for all the information about the world that is translated into decoration in Kenneth Jay Lane jewelry—the serpent bracelets of the odalisques, the gold collars of the Aztecs, the enamels of Indian royalty—its fun lies in the fact that it's about dressing up and having a good time, like the man who creates it is doing.

As he studies a catalogue for yet more things to collect and yet more places to visit, he peers over his reading glasses to inquire, "Did you know Scaasi is Isaacs spelled backwards? Do you think I should have changed my name, too?"

You can take the boy out of Broadway but you can't take Broadway out of the boy. So guess what Lane is, scrambled? That's right. You've got it. Elan.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now