Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

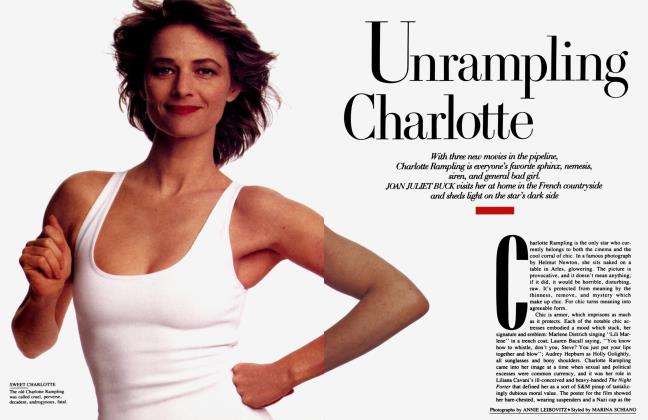

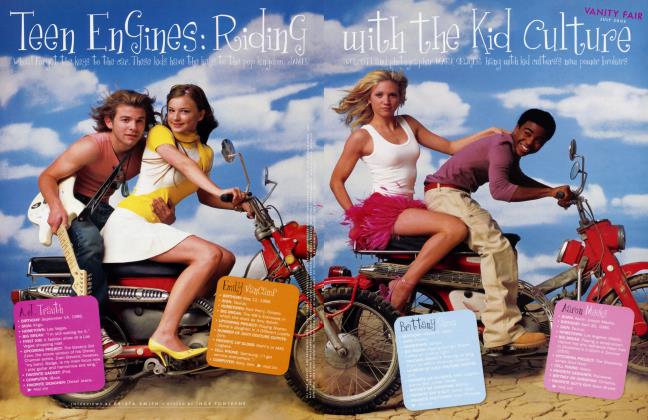

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHollywood Knives

What is the real story of David Puttnam's tumultuous year as head of Columbia Pictures? Why did half of Hollywood, from Ray Stark to Warren Beatty, set out to get him? What went wrong with Coca-Cola? And what was the Bill Cosby connection? TINA BROWN finds out

The day David Puttnam resigned as chairman of Columbia Pictures, after just one year in the job, the Hollywood producer Ray Stark came on the phone to accept an invitation to a Vanity Fair party. "Well, darling, it's a bad day for Rule Britannia," he commented genially. "Your compatriot turned out to be a real asshole, didn't he? He should go off and be a professor somewhere. ' ' Stark was one of the adversaries who had sought to disenchant Coca-Cola, the owner of Columbia, with its new hire from Britain. As a major Coca-Cola shareholder, and the producer of two of Columbia's greatest money-makers, Funny Girl and The Way We Were, he has always enjoyed special influence. Now he was savoring a coup. Not only Puttnam had gone, but also Fay Vincent, the president of Coke's entertainment-business sector, who had head-hunted Puttnam. The man taking Vincent's place as head of the merged Tri-Star and Columbia was Tri-Star's Victor Kaufman, a Stark protege. Vincent had been put in charge of Coke's bottling investments.

Two days after Stark's call, David Puttnam threw himself down on a sofa in a New York apartment next to his wife, Patsy. "It's Fay Vincent I feel sorry for," he said. "They bottled him, you know.

"I've got a new F-word," he added. "Family! The CocaCola family I used to hear so much about."

The last time I had run into Puttnam was in the Speedwing Lounge at London's Heathrow Airport on his way back to Los Angeles after Christmas at his mill in the Wiltshire country side. "What I love about Coke," he had told me then, "is how up-front they are. I've got three years to get results and they're going to leave me totally alone to get on with it. Wonderful, isn't it, American business?"

"I was rock 'n'roll up to my eyebrows?

Now, a year later, the deposed Puttnam looked toxic with fatigue. He is one of those people who go into high gear under pressure. He paced round and round, tugging his two-tone beard and talking even faster than usual. Patsy was unrattled. Slim, blonde, and gutsy, she remains a proud sixties girl who rarely wears makeup or moderates her demotic candor. Like David's, her conversation crackles with Cockney slang. They weren't merely surprised by Coke's financial maneuver. In Patsy parlance, they were "gob-smacked."

Puttnam was in philosophical overdrive. "Hollywood plays to your weaknesses," he said. "Whatever you are, it makes you more than you want to be. If you're a bit aggressive, it makes you very aggressive. If you're a bit deceitful, it turns you into a liar. It's literally a godless place. I cope with it very badly, I'm afraid."

Puttnam arrived in Hollywood a bit angry. He left it very angry indeed.

If any of the films he has produced defines the psyche of David Puttnam, and illuminates what happened in Hollywood in 1987, it is Chariots of Fire. Not only because it was a huge success, beating out Warren Beatty's Reds for the Oscar for Best Picture in 1982, but because it synthesizes Puttnam's inner conflicts in a victory of self-definition.

David Puttnam's own race for success began in the sixties, when he was a flash rock 'n' roll kid from a ■ London suburb who zoomed up through the advertising business. After a spell as a photographers' agent (representing David Bailey and Richard Avedon), he graduated to producing movies, classy little pictures like That'll Be the Day and Bugsy Malone. Inevitably Hollywood beckoned and he made his big bid for the American mainstream with Midnight Express. As Puttnam had hoped, it was a box-office success, but he felt uneasy about it—with good reason. Oliver Stone's screenplay, directed by Puttnam's friend and fellow Brit Alan Parker, was about an American hashish smuggler's ordeal in a Turkish jail, and it was lurid stuff. The film was attacked for its sodomy, swirling music, and racism. Puttnam felt he had yielded to the sirens of Hollywood by exciting the crassest appetites of the box office. The first public screenings of Midnight Express were traumatic for him. "I expected the audience to dive under their seats in the scene where the trusty gets his tongue bitten off, but instead they started to cheer. I was horrified. I realized the extraordinary impact of the medium we don't fully understand."

While Parker rejoiced in the movie's runaway success, Puttnam went back to London and sought out a Jesuit priest. Father Jack Mahoney told Puttnam he could resolve his conflict by using his skills to make films that could enlarge the moral life of an audience. For Puttnam, feeling he had betrayed his British values, the priest's words became a challenge to reinvent an image of Great Britain through the medium of film. His epiphany came in the fall of 1978, back in Hollywood, when he was sitting in a rented house in downtown Gomorrah leafing morosely through a history of the Olympic Games. He was intrigued by the account of two 1924 gold medalists named Harold Abrahams and Eric Liddell, and he saw the germs of a moral and patriotic idyll that promised to lift him out of the self-loathing he felt after his lucrative bout with grunting Turks.

The film Puttnam made, Chariots of Fire, was a squeakyclean classic that not only absolved him of guilt but also reconciled the two sides of his nature. Abrahams, the Jewish outsider in the Cambridge establishment, competitive, professional, a passionate meritocrat, flawed by his fierce desire for glory, is very much a Puttnam figure. Puttnam, half Jewish and selfmade, has always felt intellectually underestimated. "I am what 1 call 'semi-deprived,' " Abrahams says. "They lead me to water, but they won't let me drink.'' He is running against anti-Semitism and elitism. Liddell, by contrast, is the pure conscience-driven hero who believes his talent is God-given and

cannot break his religious principles to run on the Sabbath. He is running for God. His idealized character is reminiscent of Puttnam's view of his father, Len Puttnam, a star news photographer with strong ideas of what England should stand for, who quit Fleet Street in disgust at the cynicism that took over after the war. Patsy Puttnam says, "David is tom between these characters, the man he is versus the man he wants to be. I don't worry about the conflict in the way that he worries."

This conflict is, I believe, at the heart of the rumpus he caused in Hollywood, but the moment in March 1982 when Puttnam went onstage before millions of television viewers to collect his Oscar was very sweet indeed. It was the moment when it all came together, when the push of Abrahams gave him the rewards of Liddell, when his runners won the race for his father's romantic Britain.

Puttnam had vowed never to set up home in Hollywood again after his experiences with Midnight Express, and battles he lost over two other movies he produced, Agatha and Foxes. With Agatha, Kathleen Tynan's original screenplay about a few missing days in the life of Agatha Christie, Puttnam could not get financing without a Hollywood star. Which is how the small part of a tall, blond, upperclass gossip columnist interested in Agatha's disappearance became the lead role in an unrecognizable story about a short, dark, American reporter played by Dustin Hoffman. With Foxes, which starred Jodie Foster and Sally Kellerman, Puttnam had wanted to make a movie about teenage suicide. After repeated Hollywood compromises, it turned into a troubled co-ed movie featuring, in Puttnam's words, "a shaming skateboard chase." When it was all over, he decided Britain was the only place he could do good work.

The man who got him back to Gomorrah was CocaCola's Francis T. Vincent Jr., who had assumed the role of the saint at Columbia Pictures in the wake of the Begelman scandal. Herbert Allen, then chairman of Columbia, brought Vincent from the Securities and Exchange Commission to run the studio. ''I knew nothing about pictures," Vincent told me, ''but I knew a lot about trouble." In Allen's words, ''nobody can lay a glove on him," and when Allen sold Columbia to Coca-Cola for the ''ridiculous" price—Allen's term—of $750 million in 1982, Vincent was the co-negotiator who made the deal go like clockwork. He also fitted well into the Coca-Cola corporate culture. The astonishing deal with Coke was the crowning moment of his business career.

It is easy to see Vincent's appeal to Puttnam. He was Father Jack Mahoney with a checkbook. Vincent is a benign bulldog of a man with such an air of paternal decency one finds oneself thinking of him as Father Vincent—and he is indeed a devout Catholic who nearly became a Jesuit priest. He was very successful as a Coke officer, running all its entertainment-business interests, but by 1986 he was looking around for someone to run Columbia. The streak of notable movies (Kramer vs. Kramer, The China Syndrome, Tootsie, and the spectacular Ghostbusters, which took in $220 million in North America) had apparently come to an end. Frank Price had come and gone as top man. His successor, Guy McElwaine, a former artists' agent who, in Ray Stark's term, was ''not exactly a rocket scientist," had a string of flops behind him and a star-studded turkey that was now about to hatch: Ishtar, with Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman, was running six months late and, it turned out, $17 million over budget. Vincent saw more trouble ahead. And so, in the spring of'86, the Saint went shopping for a prince of the movies who would take the Columbia Lady away from all this. He was still without a suitor when he lunched one day at his office with a lawyer in the entertainment business, Tom Lewyn. Lewyn, as it happened, represents David Puttnam and had just pulled out of negotiations with Paramount, who had been trying to persuade Puttnam to come aboard with the current studio head, Frank Mancuso. Puttnam, fresh from his triumph with The Killing Fields and confident that The Mission was the best thing he had ever done, was insisting on total control. He was by now more than an acclaimed producer. He had become the white knight of the film industry in Britain, a crusader who was never off the feisty liberal slot on television. Vincent asked Lewyn what it would take to get a man of the caliber of, say, David Puttnam to come to Columbia. Lewyn, who had Puttnam's rejection letter to Paramount in his briefcase, replied, ''I can tell you exactly what it would take."

It added up to $3 million a year, autonomy for any picture up to $30 million, with control over production and also over marketing and distribution worldwide. (Continued from page 102) And a mandate to produce quality.

(Continued on page 155)

Coca-Cola gave Puttnam "a mandate to make films, not enemies."

(Continued from page 102)

Vincent, unfazed, flew to London with Lewyn and Dick Gallup, the president of Columbia Pictures Industries, and found Puttnam in a typical Abrahams-Liddell split. Abrahams had been flirting with Paramount, but Liddell had accepted a fellowship at Harvard from October 1986. Patsy had just returned from scouring Boston for an apartment. Either way, he had decided to flee. Since the death of his father in 1981 he had been re-evaluating his goals. His dream of recreating a powerful British film industry and, in the process, of reinventing the England his father had believed in had taken physical shape in the Wiltshire countryside. He had bought a millhouse as old as the Domesday Book, added a cutting room (he cut The Mission there), and worked to make it a creative nerve center for filmmakers, like his friend Robert Redford's Sundance Institute. But by the time Father Vincent flew to London breathing big bucks and the Coke religion, Puttnam's dream had soured. During his years in L.A. he had come to idealize England as a slice of Masterpiece Theatre, only to find when he got back that it had become My Beautiful Laundrette. Slogging away to make his quality films, he felt a mounting re-sentment toward his dependence on foreign investors. Even the money for Chariots of Fire had come from overseas. "He carries a national anger on his shoulder,'' says Alan Parker, "that England can't be a power anymore.''

At age forty-five Puttnam was out of sympathy with Mrs. Thatcher's England; he had lost a fight to stop a duopoly taking control of British cinemas; and his power base at Goldcrest Films, sponsors of Local Hero, The Killing Fields, and The Mission, was on the rocks. Goldcrest was supposed to be dedicated to low-budget, high-quality films using the best British talent available, but in 1985, over his vehement objections, it decided to make Revolution. Originally it was conceived as a naturalistic docudrama of 1776, but Chariots director Hugh Hudson passionately wanted A1 Pacino to play the lead despite a Hollywood price tag of $2 million. Puttnam had never forgotten how a big star had altered the chemistry once before, on Agatha. On Revolution, Pacino behaved well, but Puttnam was proved right (and Hudson wrong): the sight of the star's seventy-foot Winnebago on the lot with smoked salmon motorbiked down to the set daily from Fortnum & Mason made everyone think they were making a Hollywood epic. The budget exploded; the film bombed and so did Goldcrest.

The great white hope of the British film industry was in a great white rage. "There is nothing wrong with the British film industry,'' he snarled, "that a few well selected deaths couldn't cure." Two weeks after Vincent's visit, he and Patsy were on a Coke plane to Atlanta.

Puttnam took Patsy with him to Atlanta—and into the meeting with CocaCola's honchos—for a very specific reason. "He didn't want me to think he had been seduced," Patsy told me. "He wanted me to hear how firm he was going to be about his conditions."

Patsy has always been David's moral safety net. The daughter of a major in the Royal Artillery with strict religious principles, she rebelled against her family to marry David when he was twenty and she was seventeen, with the first of their two children on the way. She didn't like the fast-track adman and photographers' agent that her husband became before his transition into films. But she believed in the idealistic David and kept that view alive for him in the social tumults of the sixties. "I idolize Patsy," Puttnam told me. "I know I've risked losing her in the past, but I've always come back just in time." He seeks her approval constantly, and her loyalty is the basis of his life. His secretary, Valerie Kemp, says, "If David said he was going to live in the Sahara desert, Patsy would fly ahead and look for the right tent." When the couple walked into Coke HQ for the meeting in the president's office, it all went so well there was only one thing missing: the Vangelis theme music from Chariots. The Puttnams were prepared to sign only if they got a declaration of independence for his tenure at Columbia, and they got everything—total authority for a revolution, and an emotional commitment to it as well. Vincent introduced them to his chairman, Roberto C. Goizueta (pronounced Goy-sw?/-ah), and the president, Donald R. Keough.

Goizueta, fifty-six, is a third-generation, Yale-educated Cuban aristocrat who fled Castro's Cuba and rose in the ranks of Coke as a flavor chemist. He is well honed and suave, the Philippe de Montebello of corporate life, given to reproving managers he considers badly dressed or fat. He beat out the six other vice presidents (known as the vice squad) for the top job by cultivating the grand old man of Coke, Robert Woodruff, who in 1981 still wielded extraordinary power from his south-Georgia plantation homestead. Goizueta, who, it was said, ''knows where every grain of sand was in the office," took to dropping in on the old man enjoying a solitary Fresca at cocktail hour. Today Goizueta is fond of saying, perhaps rhetorically, ''I wake up every morning and ask myself, 'Should I have left Cuba or stayed and fought?' " When Goizueta took over Coke, he made his principal rival, Don Keough, into his chief operating officer, and ran the company as a double act of Roberto and Don. The Irish-American Keough, who plays golf with Bill Cosby, is a useful alter ego, a gregarious networker who is as irresistibly personable as Goizueta is aloof. He has an Irishman's gift for the blarney. Praising Merv Griffin to the Coke empire, he reminded his audience that Merv ''has so much money he could burn a wet elephant with it." His forte is selling Coke to the world, and the Coke corporate culture to its employees—he complimented Merv on having ''a sense of warmth and a sense of caring and a sense of love that makes us all feel like we are part of your family."

Puttnam handed these men his own hymn sheet, two pages of passion about America and its influence on the world through its movies. When he first came to America, in 1963, Puttnam's credo said, he felt part of him was coming home. ''Far more than any other influence, more than school, more even than home—my attitudes, dreams, preconceptions, and pre-conditions for life had been irreversibly shaped five and a half thousand miles away in a place called Hollywood."

Goizueta murmured appreciatively, "You're right. You're right. When I came from Cuba, this is what cinema meant to me. We're ashamed of what we have now."

Puttnam's manifesto swept on. "The medium is too powerful and too important an influence on the way we live—the way we see ourselves, to be left solely to the tyranny of the box office or reduced to the sum of the lowest common denominator of public taste."

The Coke chorus was transfixed. What did it all mean? Puttnam spelled it out. Columbia could make films without stars who took pictures over budget. It could make them without packages from agents like Michael Ovitz of Creative Artists Agency who tied up stars, script, and director and presented them as a costly fait accompli. It could make them with firsttime directors, as many of his own pictures had been. To do this it had to internationalize the studio and address the overseas market—an attractive notion to Coke, which has two-thirds of its sales overseas. All this could reverse a trend that had led to a staggering 400 percent increase in the cost of film production since 1977.

Roberto and Don listened to this radical credo and embraced it all with an alacrity that left Patsy gob-smacked. The only thing they didn't like was Puttnam's insistence on a three-year rather than five-year contract. It didn't seem long enough to accomplish all this, but Puttnam was adamant. The three-year limit was crucial to his self-image as an artist and rebel on temporary assignment as a Suit. "Every time I opened my mouth, they concurred," says Puttnam. "I told them that they had only two choices. They could either bring together the major producers, like Ray Stark, Peter Guber, and Daniel Melnick, and fund them as oarons with their own territories, which meant they would have no control over what they did, or they could do what I wanted, which was to restore the studio's role and offend all of the above. Columbia had become a state run by a weak prince with the barons calling the shots. Some of the barons were good, some less good, but Columbia was a power vacuum being run from the outside by greedy agents and producers."

Abolishing the star system, the barons, and the agents was no sweat to Coke that morning in Atlanta. "We're big boys at Coca-Cola," said Keough, laughing heartily. "A thousand times theater people come to us and say, If you don't do this or that we're going to pull Coke and use Pepsi, and we say, Congratulations, go with Pepsi. As for Stark, we'll take his calls and be polite, but have no worry on that score. In the Coke family, we back the people we hire."

This was what Patsy had come to Atlanta to hear, that when the going got rough her man would not be betrayed. "I've seen so much of the promises people make to each other, always in good faith,-and somewhere something goes wrong. Don't try and change David," she told the big boys of Coke. "People think they can because he seems amiable, but they can't. He will give you blood, sweat, and tears, but there are a lot of people who are going to go for his back. You have to protect him if he is going to do this for you. We'll be moving away from our eountry, away from family and our home."

After her Churchillian aria, Patsy recalls, "I swear a tear came into Roberto's eye."

Except for the photo gallery of stars from its glory days in the halls, Columbia Pictures' Burbank Studios resembles a hideous summer camp. In scrubby foothills lanced by the Ventura Freeway, it is two stories of dark-stained wood, its identity proclaimed on a giant water tower in the center of the lot. Columbia Plaza South houses accounting, publicity, and advertising. The Producers Building houses Ray Stark's production headquarters. Puttnam installed his honeycolored Biedermeier furniture from London on the second floor of Columbia Plaza East, and a comer of England in the outer office. Valerie Kemp, the personal assistant he brought from London, is straight out of a British Lion film of the fifties, with wavy brown hair and sweetheart neckline. Even in moments of deepest crisis, there were bluebirds over / the white cliffs of Dover / when Valerie Kemp got on the horn.

From the day he arrived in Hollywood, Puttnam was Liddell in overdrive He went at the job "balls high."

He explained to me, "I only had three years. I didn't have time to piss about." Today he knows that the frontal approach was a mistake. Paramount and Disney have both achieved many of the things he wanted to do by keeping a low profile. They have reduced the number of agent packages and failed to bid on exorbitant projects, but they have done it quietly. "They were a lot more subtle than I was, let's face it," Puttnam agrees. But he also knew he couldn't have done it any other way.

Puttnam's attitude to power was forged by the class wars of England and the radical impulses of the sixties. He was a baby of the Zeitgeist. It is instructive to see the Puttnam of that era caught by the lens of David Bailey in his portfolio of sixties shakers like Paul McCartney and Michael Caine. There he stands, cocky as a Joe Orton character, thumbs flaunting his pelvis, jacket groovily slung over his shoulders, giving Attitude under a Beatle fringe. "I was rock 'n' roll up to my eyebrows," he says now, but the Attitude has its roots in an unshakable class ethic. Twenty years later he has the same friends, the proletarian meteors of the sixties whom he worked with in advertising and who are still bright sparks today, such as copywriter Charles Saatchi, now the world's biggest advertising tycoon, photographers David Bailey, Terence Donovan, and Terry O'Neill, directors Ridley Scott (Alien), Adrian Lyne (Fatal Attraction), and Alan Parker (Angel Heart). The filmmakers of the group are known in Hollywood as the British mafia. They are a macho gang who share ruffian wit, driven talent, and heterosexual energy. They are all bitter romantics about England, carrying their country in their hearts while their heads despise its material limitations.

Puttnam in power was answerable first to his Liddell side and second to his class ethic, a stubborn belief that what you are and what you do are somehow connected. It means saying what you think, believing what you are told, your mates are for life, and Don't Mess Me About. When he started blasting Hollywood excess, it was partly for the ears of the British mafia. He wanted to make it clear he hadn't joined the glitz on the other side.

For this reason he had to take on the big boys right away, and there are few bigger than Ray Stark. "David's a very strategic man," says Alan Parker. "My guess is he wanted to test Coke and see if they were serious."

Stark is not only part of the system of independent baronies that Puttnam wanted to quell in favor of studio power. His relationship with Herbert Allen, a member of the Coke board close to Roberto Goizueta, and the former principal shareholder in Columbia, is one of father and son. Allen, the former chairman of Columbia, comes from an investment-banking family. His father and uncle founded the Wall Street investment firm Allen & Company. His best friend, Stark, was the architect of the deal in which Allen bailed out Columbia for $2.5 million in 1973. And Stark showed his friendship again by throwing his own shares behind Allen when Kirk Kerkorian tried to take over Columbia in 1979. Allen made a whopping $40 million profit on the sale to Coke in 1982. Stark continued to be an eminence grise at Columbia, regaling Allen in New York with the buzz on studio politics. As a board member Allen is not merely a nominal power with Coke, he is chairman of Coke's compensation committee, responsible for giving Goizueta a bonus of "performance units" worth $6.4 million the year of the newCoke fracas for "his willingness to take risks." Inevitably, Stark's telephone buzz proves useful background for assessing the performance of executives at Coke's Columbia.

Raymond Otto Stark has always enjoyed being on the inside track. Now seventy-two, he has stitched himself deep into the secrets of Hollywood life. At the 1980 Oscars he was honored with the Irving G. Thalberg award. Like Scott Fitzgerald's Monroe Stahr in an unlikely way, he is one of the few producers left who carry "the whole equation of pictures in their heads. " The clue to his self-image looms outside the breakfast-room window of the Georgianstyle house in the Holmby Hills where he has lived for almost thirty years with the sflme wife, Fran, the daughter of Fanny Brice. Among an extraordinary art collection of Braque, Leger, and Magritte is a sculpture garden of Henry Moores. (He has so many, he once sent Moore a cushion embroidered with the words "The Moore the merrier.") The particular sculpture he looks out on over his morning orange juice and coffee is a Giacomo Manzu of a somber life-size bronze cardinal. In movieland's Vatican City, this is Stark's unique role—the profane cardinal of Hollywood. Stark, to his friends, is a warm, loyal, and funny man. But to his enemies he is a demon. Cross him and he becomes the hound of hell.

Stark was not hostile to Puttnam's arrival. He had admired the younger man's work, and at the time of Midnight Express asked Puttnam and Parker to make a picture for him. Puttnam declined, but Stark had continued to be an admirer and liked calling Puttnam "the second-best producer in the world." A year before Puttnam arrived at Burbank, Stark had put out feelers for him to join Columbia, but Puttnam hadn't bitten. So Stark was mildly miffed when Vincent snared Puttnam himself, instead of using him as the go-between, and was mildly mollified to receive Puttnam for tea in the garden in the summer of '86 before Puttnam officially took over at Columbia. The Cardinal was even more pleased when Puttnam sought his counsel. He learned that one roadblock remained in Puttnam's negotiations with Coke. Control of international marketing and distribution of his films was crucial to Puttnam, but this was Coke territory and it meant making awkward staff changes. Stark said he would make a call. Clearly this was effective, because shortly afterward Puttnam got what he wanted. But on that summer afternoon Puttnam made it clear that he was going to ignore Stark's "special relationship" with Columbia and was going to treat him like everyone else: he could be either a producer or a consultant but not both. "I said, Ray, you've got to be one or the other. I can't come and ask you for advice if I know there's a script sitting on my desk from you. Ray told me, I'd much rather be an adviser. I can always get my scripts made at Universal."

Soon afterward Puttnam got a surprise packet: a script from Ray Stark. "He seemed to have forgotten our talk, so I let it go and read the script on the plane to London." It was a story about the twenties torch singer Libby Holman by Jim Bridges that Puttnam thought was old hat. "I thought, Oh, Christ, here goes. I called Ray from London and told him straight off I thought it was a backstage Fanny by Gaslight and it wouldn't work for Columbia. He said, Thanks for being quick."

It didn't occur to Puttnam-Liddell that when Stark did Puttnam-Abrahams a favor on the marketing problem, he expected a favor back. These are the rules of the Hollywood game that Stark and his peers have always played by. In a business of fast-revolving chairs and a frightening variable of hits and flops, the only constant is the favor bank. And the players expect it to be respected. David Picker, the seasoned Hollywood man whom Puttnam hired as chief operating officer, told me, "Ray works on the basis of quid pro quo, but there are no quid pro quos in the world of David Puttnam." Stark wanted to play by the rules of Hollywood hardball, Puttnam by the rules of the Olympics.

In September, two weeks after Puttnam took over officially as chief-executive officer of Columbia Pictures, he got a call from Ray Stark. Puttnam recalls, "Ray said, Why haven't you called me? You've been here two weeks. I thought you wanted me to help. I said, Christ, Ray, my feet haven't touched the ground. I'm living in the Bel-Air and reading scripts all night. He said, You'd better get over here." It was a breakfast meeting, and as Puttnam parked his Audi in Stark's statue-flanked driveway after a sleepless night in the Bel-Air hotel, he was tensed for a showdown.

Stark was sitting against the window, and Puttnam found himself looking intently at his backlit ears. "Have you ever noticed them? They're funny pointed little ears you can see the light through." Stark, for his part, was mesmerized by Puttnam's teeth. "They're not teeth, darling," he told me, "they're fangs, fangs that haven't been to see a dentist lately." Clearly, the only movie these two men could make together was An American Werewolf in London II.

According to Puttnam, the lines went like this:

Stark: "Am I going to make pictures at Columbia?"

Puttnam: "What do you mean?"

Stark: "I want to know once and for all: am I making pictures at Columbia?"

Puttnam: "It will all depend on the script."

Stark: "Don't be a smart ass—what's it got to do with the script?"

Puttnam: "I've been given a mandate, Ray, and the mandate relates to scripts I think will work. If I start making scripts other people think will work and I don't, I shouldn't be here. Why don't you run the studio?"

Stark, flippantly: "I could never see a way of making a buck." (In fact, Puttnam had touched a raw nerve. In the throes of the Begelman scandal in 1977, Stark had offered to run the studio for no fee, and Alan Hirschfield, the then president, had rejected him on the basis of a conflict of interest.)

Halfway through the breakfast. Stark took a call from Michael Ovitz, the superagent Puttnam had already told Coca-Cola he would challenge. Like Stark, Ovitz is a serious art collector; he has a clutch of Schnabels, and I. M. Pei is designing his new offices. Both Stark and Ovitz were founders of Hollywood's secular church, the Museum of Contemporary Art. Stark now gave Puttnam one last chance to join the congregation of Hollywood heavies: would Puttnam like to join him, Ovitz, and others on a private preview of the new museum? It was a key test. And Puttnam failed it.

"No thanks, Ray, I'm too busy reading scripts," he said.

"You'd better get your priorities right," retorted Stark, wounded in his sense of himself as a man of taste and generosity.

Puttnam, feeling the invisible presence of another big boy in Ovitz, took them all on. "It bothers me you have relationships with Herbert Allen and people like that," he blurted.

Stark replied, "I can fight my own battles. I don't need Herbert, I don't need anybody."

Puttnam persisted: "Well, it troubles me. It's quite clear that a lot of executives at Columbia had a very bad time. Frank Price (a previous C.E.O.] was frightened of you."

"It's a lie. Frank and I are close friends," said an angry Stark.

"Well, that's not the impression I've got," threw back Puttnam, "but I'm not frightened of you and I'm not going to be intimidated by you, and if that means we can't talk to each other, then we can't talk."

The deteriorating meeting ended abruptly when Stark's brother-in-law, the painter William Brice, came down for breakfast. "This is one of the greatest painters in America," said Stark grandly when it was clear Puttnam had not heard of him.

Out on Sunset Boulevard, a shaken Puttnam put in a call on his car phone to Fay Vincent in New York. Vincent already knew about the scene that had just gone down. In the time it had taken Puttnam to get through, Stark had made his own call. A few hours later, he followed up their stormy breakfast by sending Puttnam another script, Revenge, a project that Columbia owned and that Stark had been developing. This time, instead of risking another phone call or meeting, Puttnam rejected it with a letter that became Stark's cause celebre.

September 16, 1986

Dear Ray,

REVENGE

I'm just off to Europe for a couple of weeks and I thought I should set down my thoughts regarding the above property.

During the past ten days I have painstakingly picked my way through the novella, The Water Hill, and the John Huston screenplays. 1 came to the conclusion last night that this wasn't a property that we'll be in a position to move on in the coming months. With this in mind I suggest the following.

We arrange either formally or informally for you to have a 90 day period in which to set the film up at another studio. Failing this, it will return to Columbia without any further lien and we'll be free to offer it elsewhere.

I say this because in reviewing the film it transpired that the material had been of interest some while ago to a team of filmmakers whom I rate highly. There is always a chance that 1 can interest them in picking up the pieces and turn out a good film at a price that makes it attractive. I'm eager not to close us out of the possibility of being able to reinterest them on terms that we could live with.

The reason for all the neuroses regarding this property is that we have over $600,000 tied up in it and most of all I'd like the use of the money!

See you when I get back.

Warmest regards,

What Puttnam thought he was doing was replying with expedition, candor, and generosity. He did not wish to commit to making the project, but was giving him ample time to make it with someone else and pay Columbia back later. But one can imagine the proud Hollywood veteran reading this between the lines of the last two paragraphs: "Thanks for jogging my memory; now I can give this script to a couple of talented kids who could do it a helluva lot better than an expensive old fart like you. See you around." Sometime later Stark turned up in Puttnam's office. "He was the only person ever to do that without an appointment," says Puttnam. He got another rejection. It was their last meeting. And from that moment, perhaps, Revenge was an apt title for Ray Stark's project.

Puttanam felt he could live with the wrath of Stark because he felt he was doing so well inside Columbia. He had the confidence of being the first filmmaker to run a studio in decades.

While Patsy rented Greta Garbo's house and worked with Henry Winkler's wife, Stacey, and Bob Daly's wife, Nancy, with troubled children in East L.A., Puttnam read about two hundred treatments and scripts in the Columbia inventory, marking them A for definite, B for develop, C for convince me, and D for forget it. Out of this pile he got a couple of projects from Jane Fonda and one from Sally Field. But Columbia was desperate for product. There were only two movies going into production from the previous regime, Roxanne and La Bamba. Puttnam cast about for instant material. He knew of Bill Forsyth's Housekeeping, which had run into financial problems. He told Forsyth he would do it on the understanding that his next film for Columbia would be more commercial, and star Bill Murray. Within a few days of Puttnam's arrival, his old friend Ridley Scott sent him the script of Someone to Watch over Me, which was in turnaround from MGM, and he gratefully green-lighted it. Two other pictures, Gregory Nava's Destiny and John Boorman's Hope and Glory, were caught in Coke's buyout of Embassy Communications, and Puttnam saved them from falling through the cracks. CHope and Glory turned into this year's sleeper, doing steady business despite the new Columbia management's releasing the film with only minimal advertising.) Puttnam recognized Daniel Melnick's Roxanne was a goer and lent his voice to securing Daryl Hannah. He backed the smart marketing decision to put out a separate, Spanish-language version of La Bamba in America, which rocketed it to success with the growing Hispanic community. Then he flung himself into creating the international studio he had promised Coca-Cola. Jane Fonda came in to talk about a movie based on the Carlos Fuentes novel The Old Gringo, which she wanted to produce and star in, with Luis Puenzo, who did The Official Story, as director.

"I love Jane—she's a real worker, no bullshit," says Puttnam, "unlike a lot of others, who earn so much money they sit around with their fingers on the bridge of their nose buying Chinese chess sets." Fonda relished his input. "David has an extraordinary sense of movie rhythm," she told me. "He said, This is a movie that demands a certain pace. He showed us where and how to make the cuts, and he was right."

Puttnam kept up his friendship with Robert Redford, and talked about ways they could work together. He bought a cottage of his own at Redford's Sundance Ranch, and while at the 1987 U.S. Film Festival, sponsored by Sundance, picked up The Big Easy, starring Dennis Quaid. In the previews it got a mixed reaction, but Puttnam told the director, Jim McBride, "I don't care, I still like it." When it did well, he sent McBride a note saying, "You made me look smart."

Puttnam developed a screenplay by William Boyd of Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa's Aunt Julia. He went all out to get the next film of Mephisto's Hungarian director, Istvan Szabo, and he grabbed a comedy about the Mafia by David Mamet. One film he pressed hard to pick up, after seeing forty minutes of it in London, was Bernardo Bertolucci's The Last Emperor. Simultaneously, he attacked staffing. He mixed Hollywood experience with new blood. When he fired Columbia's president, Steve Sohmer, he hired David Picker as his chief operating officer, who had been responsible for Saturday Night Fever and Grease when he was at Paramount, and had previously been the production head of three studios. To oversee marketing and distribution, he imported Greg Coote from Australia, who had run Rupert Murdoch's TV stations and his own company, and from PBS television William Wyler's daughter Catherine, to head up a new nonfiction department. While every studio develops true stories garnered from the media, Wyler's title created a magnet for them. She developed a movie based on the life of Benigno Aquino: Puttnam flew to the Philippines twice to secure Mrs. Aquino's cooperation. Wyler developed another about the Chernobyl disaster: Puttnam flew to Moscow to see what access they could get. In the course of all his travels he stroked Columbia's depleted foreign managers, the best of whom had left to go to Warner Bros, in May 1987, when Warner's said it no longer wished to share foreign distribution with Columbia. Jaded by years of successive Columbia overloads, the foreign managers chose Warner's. Puttnam realized to his chagrin that his foreign system would have to be reinvented from the ground up.

Puttnam was everywhere. He would wander onto the back lot to watch them shoot, trying not to let the crew notice that the C.E.O. was around. His spirit swept away the hushed, paranoid corridors of closed doors and whispered meetings that used to be Columbia. He let the staff in on what the studio was doing with a seminar preview of each new movie, filmed for the archives under the title The Reel Truth, and they adored him. Existing Columbia staff like Fred Bernstein and Michael Nathanson, in charge of worldwide production, recall their sense of exhilaration. Nathanson had come in during McElwaine's time and expected to be fired. Puttnam stalked into Nathanson's office to tell him, "Your salary sticks out like a sore thumb. I hope you're worth it." To test his mettle he put him in charge of Ridley Scott's Someone to Watch over Me. Nathanson says, "Puttnam has the best postproduction mind of anyone I have ever met. What I learned most from him was his attention to people, detail, and feelings. Three months later he told me. You're on my team. After that, I knew he would always back me." Greg Coote was joyously surprised: "The only person I've met with who has a business brain as smart as Puttnam's is Rupert Murdoch." Puttnam worried over Columbia's money as if it were his own. He brought spending down from an average cost per film of $14.4 million to $10.7 million.

A whiff of the excitement clearly reached Coca-Cola. In January, at a Coke entertainment-business summit in Santa Barbara, Roberto Goizueta told his audience, "David Puttnam, David Picker and the team they have assembled have taken the first steps down the road that we believe will lead to an unprecedented era of creativity at Columbia Pictures. This leadership is going to give the studio a personality, a character, a style, such as the studios had during the Golden Age of motion pictures." Keough enthused: "David Puttnam... had the guts, sheer guts, to say, O.K., I'll do it, I'll do it my way. And it is courageous for him and his wife, Patsy, to leave a kind of wonderfully comfortable cocoon and to step out of it and to come out here, where you know every agent in town is out to get him." Two months later the big three, Roberto, Don, and Father Vincent, visited Columbia at Oscar time for a preview presentation of the movies in the works. They were overjoyed. At dinner afterward, both Goizueta and Keough made impromptu speeches voicing their delight. Goizueta focused on the need not to be swayed by outside skepticism or difficulties. "You may have some disasters as well as successes," he said, "but just ride through them."

By May 1987 the atmosphere inside Columbia was so bubbly that Puttnam came back to his office late one evening and found two young executives playing table tennis in the once paranoid corridor. Something happened to him which he had not bargained for: "I fell in love with the Columbia Lady."

The core of Puttnam's manifesto to Coke was that he was not going to be hijacked by stars and their agents. As president of Creative Artists Agency, Mike Ovitz is one of the key players in Hollywood today. He looks boyish and low-key until you see him in action, cutting to the core of a deal with lethal concentration. Ovitz's charisma lies in his personal restraint and his outrageous demands. His power is not simply in his unpublished client list (such names as Martin Scorsese, Robert Redford, Dustin Hoffman, Sylvester Stallone) but in the way he has brilliantly usurped the traditional role of the studio as a packager, putting together directors, writers, and stars in unbreakable combos. He runs his company with Japanese efficiency. CAA agents are all Moonies for the cause.

Puttnam and Ovitz had one reasonably cordial dinner at Spago before they clashed, first over Dan Aykroyd and then over Bill Murray. Before Puttnam arrived, Columbia had signed Dan Aykroyd to appear in Vibes, a wacky movie about psychics. Puttnam saw some tests of Cyndi Lauper and decided she was the one to play opposite Aykroyd, but Aykroyd didn't want her. He felt that a novice director, Ken Kwapis, and a first-time co-star, Cyndi Lauper, put him at risk. Even though Aykroyd's deal did not include casting approval, Ovitz demanded that Columbia drop Lauper. Puttnam dropped Aykroyd instead, casting Jeff Goldblum opposite Cyndi. The Columbia staff was elated. ''This is the first time," said Puttnam, ''that they felt like a studio instead of being terrorized into deals by agents." Puttnam wrote to Aykroyd saying he hoped they could work together, but got no response.

Ovitz was reportedly furious that Puttnam had written directly to Aykroyd. Still more serious was another spat over a star a month later. The New York Post's ''Page Six" reported that Puttnam, speaking at the British American Chamber of Commerce luncheon, had taken a swipe at Ghostbusters' Bill Murray for not putting something of his enormous earnings into the industry, as Redford did with Sundance. Columbia was at this time hoping to make a deal on Ghostbusters II with Ovitz and Murray.

Puttnam swears, "I never mentioned Bill Murray when I spoke. Bill Murray's lawyer was supposedly at the lunch. This figure, this phantom, supposedly left in disgust. He has never come forward and identified himself." Puttnam got no fewer than seven letters from others at the luncheon, all of them denying the story and expressing shock: Trevor Valentine of the B.A.C.C.; Shep Gordon of Alive Films; accountant Duncan MacCorkindale; lawyer Nigel Sinclair; Barry Spikings, president of Embassy Home Entertainment; Richard Lucente, a British Airways vice president; and Jerry Pam, president of Guttman and Pam. Pam wrote, ''I recognize that there are jealousies in this town when an outsider comes here with the power that goes with your position. That's the only reason I can assume that these comments were fabricated by someone and given to the paper." Puttnam was dismayed that Bill Murray's wife was upset by it all. He mailed the letters to Ovitz and Murray. To Ovitz he said, ''Sadly, I gather that even you are tempted to give credibility to this shoddy gossip. Michael, please understand that to do so characterises the writers of these letters as well as myself as liars." Ovitz never replied.

Why does almost everyone in Hollywood nonetheless believe Puttnam attacked Murray? I could find not one person who would go on the record to confirm the Post story, though many "friends of friends" insisted the remark had been made. The Murray affair became Puttnam's Marabar Caves. Had he laid a hostile hand on Murray? Or was Hollywood frightened by an echo of Puttnam's angry buried self?

Whatever Puttnam may have said, Hollywood believed the scurrilous "Page Six," rather than the denials of his distinguished witnesses, because it seemed in character with all Puttnam's other pronunciamentos. Puttnam has always been a man of reckless, indiscriminate candor, and he's no different with the press. His old friend David Bailey has a yellowing twenty-year-old clip stuck on his art board from the days when Puttnam was a photographers' agent. It reads, "I've used representing photographers [like Bailey himself] to move on to bigger and better things." As Fay Vincent said to me, "David instantly made his private agenda his public agenda. I had no idea that he would go public with the fact that his contract was only for three years, but as soon as he got there he told the press." Had Coke troubled to read Puttnam's clips, they would have had an idea. In England he had always been a sophisticated user of the press, making the most of his facility with a vivid quote to promote his movies. He was tireless at it. As James Lee, the former chairman of Goldcrest, says, "When the movie wrapped, no one except David would have the energy to go and sell it on Finnish radio. " It should have been no surprise, therefore, when Puttnam went public about his three-year contract, and did so in typically colorful terms. "I like a scrap," he told the London Daily Telegraph, from where it was picked up around the world. "It's a working class thing. Screw you. I don't need any of you. I leave here in March, 1990. I have the date ringed on the calendar. If I make good movies and they don't work I will go with my head held high. Suck it and see."

Puttnam justified his media blitz by saying it was only his desire to communicate directly with the creative community "to speed up the process." One such interview comment went: "Where do they get off asking for that much? Is it just because there's some schmuck somewhere in a large tower in Century City that's got the balls to ask for it?" It is unlikely Michael Ovitz, sitting in his large tower office in Century City, felt his creative juices needed that kind of stimulus.

Why did Puttnam choose to offend as well as oppose Ovitz? Puttnam didn't seem to realize that all his publicity was counterproductive. His friends like Terry Semel at Warner Bros., Jeff Berg at ICM, and his own David Picker counseled and even begged him to go underground. Others were less friendly—like Barry Diller at Fox, who remained irritated with Puttnam for taking an ungracious swipe at Reds when Diller was at Paramount. Puttnam had given an interview to what he thought was a local paper saying that Chariots of Fire had been put together with pennies, while Reds was one long spending spree. Now Diller saw Puttnam as a humongous hypocrite, condemning Hollywood greed but drawing $3 million a year himself. The truth is that the more culturally alienated Puttnam felt in Hollywood, the more he felt the need to talk aloud—to himself. At the bottom of his tirades was, I believe, his fear that Puttnam-Abrahams would make a Faustian pact with Hollywood and never go back to England, and a sense of shame that he had reneged on the ethic of the Cockney mafia. To head off that temptation, Puttnam's Liddell side publicly reprimanded his Abrahams side and insisted on holding him to his word. Alan Parker saw it happening. "He didn't like himself for the job he was doing. The only way he could live with it was to come at it in a combative way."

If Columbia seemed like Camelot inside, outside there was a town of bottom-line skeptics, and Puttnam's press didn't help. Over at Disney they christened Cathy Wyler's project on Chernobyl Towering Reactor. Over at Creative Artists, agents complained that every time they put up a package with an expensive director, Puttnam snorted, "Why should I pay that when I can get Istv£n Szabd for half the price?" A typical reaction among the Hollywood heavies came to me from Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, whose Beverly Hills Cop II was the biggest box-office hit of 1987. They also produced Top Gun. Out of the blue they called to give me their riff on Puttnam. Simpson and Bruckheimer are very easy to tell apart: Simpson is tan and manic, with a bosky beard; Bruckheimer is thin and watchful and crouched in a harrowing silence. Simpson loves to expound what he calls his parking-lot theory. "You know, you go to a movie, you think it's great, then you walk to your car and think, Nyehhh, so what? That's the parking-lot theory." None of Puttnam's movies, in their view, survived the parking lot except Chariots of Fire. "But Puttnam is a great producer," Simpson said, "because he cares. That makes everything he does important."

As Paramount's golden boys, Simpson and Bruckheimer had not been in a mood to switch studios, but they were intrigued enough with Puttnam to go for an exploratory lunch. "All that stuff, that nonfiction division, that crazy Baron Munchhausen project, those directors with foreign names," Simpson fizzed at me. "I said to Jerry afterwards, He's nuts, and I say this as someone who used to run production at Paramount. We discussed it back then. Charlie Bluhdom was Austrian, and he wanted his studio to be international just like Puttnam. Barry Diller and Michael Eisner used to listen and say, Screw you, Charlie, you're crazy. It's a lousy idea. Movies are a science."

"It's not magic that we do, Tina," said Bruckheimer lugubriously.

If Puttnam got the distinct feeling that every time he opened his mouth some hostile Boswell would see that the world heard a version of it, he was right. Ray Stark amused himself by recycling Puttnam banana peels to press people short a paragraph or two. Warren Beatty was also no friend. In the summer before Puttnam took over the job, Beatty had gone to see Fay Vincent to voice his reservations about Puttnam. He told Vincent, "I don't like him. We don't get along. After me he's the best producer in the world, but he's not going to help with Ishtar." To avoid confrontation with Beatty, Puttnam stayed away from his movie. In fact, he never even saw it: he couldn't trust his own mouth if he did. Now, smarting from the flop of Ishtar, Beatty tried to pass the buck by blaming Puttnam's lack of enthusiasm for the movie he'd been lumbered with. He took to sending his rat pack clippings from any far-flung journal that might have caught Puttnam on the wing with the scrawled inscription, "Look what the asshole is saying now." The press leaks were so common, a friend told Puttnam one of his enemies was having him followed. Puttnam was concerned enough to go and see the godfather of Hollywood, Lew Wasserman, chairman of MCA. Wasserman said, "It wouldn't be the first time," but reassured him, "They'll soon get bored."

The Hollywood establishment became increasingly mad at Puttnam's quoted attacks on their way of life. Each successive interview turned him further into a selfappointed prophet on a rock, banging on about the sins of Gomorrah. Alan Parker had a go at him for speechifying too much. He felt it destroyed the perception of the other, endearing Puttnam, who is nothing like the messianic persona Hollywood tired of. Indeed, Puttnam in closeup is warm and likable and wound up with vitality that dissolves into wild laughter when he thinks about some of the fights he had in Hollywood. Under the aggression, there is something very sweet about him, something victoriously naive that is an echo of the sixties. "I used to say to him," says top agent Jeff Berg, " 'David, don't wear your idealism on your sleeve. The Pink Floyd don't play together anymore.' "

For Puttnam the problem was a culture clash—two nations divided by a common language. Puttnam talked the patois of the creative community and they loved him, but his lack of corporate style was puzzling to Hollywood—and to Coca-Cola. There is, for instance, his addiction to letter writing. It takes some time for an Englishman working in sophisticated American business to realize the loaded, almost sinister overtones of communicating by letter. These days in the corridors of power the mail contains only invitations to black-tie dinners, circulars, or bills. It is as if without open discussion a consensus has been reached. Forget about letters. There are only two reasons to write one— to intimidate the recipient by having a copy on file, or to reject somebody. Otherwise you get on the phone. A studio head receives 120 phone calls a day, all of them urgent, all of them from famous people who steam for a response. Mr. Spielberg is on the line! Ms. Streisand is on line 2! Mr. Coppola is holding! Woody Allen is on 3!

Recalling his days as head of Paramount production, Don Simpson remembers the phone calls, with their insistence on instant decision-making, as the single most hysteria-inducing aspect of his life. Hollywood business machismo requires that the calls be returned the same day, otherwise The Town deems you the lowest form of human life: "an asshole who doesn't return his phone calls." The result, as Simpson recalls, is "malignant fatigue.... I was fifty pounds heavier because those 120 phone calls consist of only one thing, telling you what a bad person you are for not giving them $20 million for a movie you don't want to make."

Puttnam, however, comes from a different culture, where the image of a boss is a man pacing while he dictates to a pretty girl taking shorthand. Puttnam was on the phone all day, but almost every evening he was scribbling on a yellow pad, as many as a hundred letters or memos a week to writers, directors, actors, agents, and producers, for Valerie Kemp's transcription.

Stark and Ovitz were not the only ones put out by Puttnam's letters. So was Coca-Cola. "It bothered them that I wrote so many," Puttnam concedes. Vincent, like Stark, misread one and thought that Puttnam was being critical when he wasn't. As time went by, Puttnam, for his part, found Goizueta, Vincent, and Keough mystifyingly indirect. It would be hard for anyone, let alone Puttnam, to interpret successfully the bland veneer of the Coca-Cola Company. Part of its puzzle is that the style of Goizueta's Coke is consensus. Goizueta's top officers are publicly associated with him on all the key decisions.

Ostensibly, Coke is the Roberto-andDon show. They have mirror-image offices next to a corporate dining room they share. They like it to be known that they work on informal chats, not memos: there are no smoking guns for hostile attorneys or memoir writers. It is a synchronized ambiguity that creates a wonderfully benign blah, but it's a facade that is tricky for those outside the magic circle. It works on understandings and understatements and shared euphemism. The newcomer has to learn that if Coke takes its surface from the affable Keough, it takes its subtext from the mysterious Goizueta. Puttnam did not understand that after Goizueta and Keough had given him their blessing, whatever cordial noises they made, they wished to return to their own aseptic stratosphere. He persisted in seeing them as individuals with whom he had a relationship, instead of symbolic figures in corporate Kabuki. At the Coca-Cola summit in January, he kept referring to Coca-Cola, Don, and Roberto, instead of Coca-Cola and Fay Vincent. Small transgressions but significant in the detail of the dance. When Daniel Melnick's movie Roxanne was released, Puttnam called Don Keough's office and asked if he would go on the Today show and give it Coke's endorsement. It was, he said, Melnick's idea, but the mere suggestion of it suggested to Coke he was strangely out of sync with the muted hum of their machine.

Another television appearance brought this home with a vengeance. One evening in June, Roberto Goizueta turned on his TV and saw David Puttnam on his screen. It was a segment on the soft-news show West 57th, which had invited Puttnam on, ostensibly to discuss the marketing of movies. Fay Vincent had given him the O.K. to appear on that subject, but in fact the interviewer chose to focus more on Puttnam's war with Hollywood. To Puttnam, his little blast on West 57th was the small change of a celebrity life. To Goizueta, it was much more than that. Something had rattled him extremely. He had been surprised, and, more than that, his deepest article of faith had been called into question. As Puttnam recalls it, "The phrase Fay Vincent used when he tried to convey Coke's displeasure was 'You don't go on network television just like that.' " It was not just Roberto's own sweaty experience with television when he had had to stand before a room full of TV cameras and confess he had made a mistake by replacing old Coke with new Coke. It was that to the CocaCola Company, television is the ultimate truth, the holy of holies, the purveyor of mass-market advertising for which they will pay a Bill Cosby millions of dollars for a thirty-second spot. Television spreads the message. Television is the message. It must be honored, earned, and obeyed, and here was David Puttnam breezily unrehearsed, treating the tube as his familiar.

Nine months into his tenure, Puttnam had no illusions that the flak was anything but intense from Ray Stark, Michael Ovitz, Warren Beatty, and company, but he relied on that sunny meeting in Keough's office when they had told him they were big boys. Over dinner in the spring Keough told Patsy not to worry about Murray or Stark or the failure of Beatty's Ishtar, "a drop in the ocean for Coke." Blinded by his Cockney truth ethic, Puttnam trusted the Coke religion. But the reality was different. For all the high-minded rhetoric and promises of backing, the Coca-Cola Company, in Steve Sohmer's words, had given Puttnam "a mandate to make films, not enemies." And Jeff Berg says, ''I never could understand why David was so idealistic about Coke anyway. He was working for a company that rots the teeth of the Third World."

The first rumblings of open discord came in May. At the Coca-Cola executive meeting in Atlanta, Herbert Allen attacked Puttnam. The two men had never liked each other. Allen is an Establishment player with loyalties rooted in money and class. Years previously, Puttnam had seen him give a £20 tip, instead of the customary £1 note, to a porter at London's Claridge's hotel, and viewed him forever afterward with distaste. Now, at this meeting, Puttnam recalls, "Allen said I was upsetting people who were powerful, like Michael Ovitz, and I just kept looking over at Keough. I said we had done $8 million worth of business with CAA, and that's a lot of money. I said, You've known all along what we're attempting to do is get control back into the studio, and it's naive to think that's going to be done painlessly. The meeting ended with agreement. I was clearly given to understand by Keough that I had more than adequately dealt with it. When it was all over I said to him, What was that all about? And Keough said, He's been grumbling a bit, and I thought it was good that he grumbled and he said what he wanted to say face-to-face."

In July, Puttnam was once again defending his position to Coca-Cola, but he thought it was a strong one because Coke was simultaneously trying to induce him to sign a five-year contract. "Coca-Cola was worried about David's short-term commitment," Vincent told me. "They felt it was not fair to pollute all these important relationships and then have him disappear. Coca-Cola felt perplexed." Puttnam did not want two more years, and for his part complained about the ambiguities in dealing with Coke. He brought with him a notepad filled with his grievances and aired them in a three-hour session in his hotel room with Father Vincent. "I told him he was Jesuitical. I never got any clear responses. It was all a gray fudge. I said, If you've got a problem, tell me."

The next day in a meeting with Vincent, Goizueta, Keough, and Allen, there were complaints about his letter writing. "I told them I've always written everything down and it's paid off. I have done twenty-eight movies, and I have only had one tiny lawsuit. Why? Because I cover everything in writing." Puttnam reiterated some of his own complaints. "I said I didn't want to sign another contract, because an atmosphere of fear permeated the company. Nobody could tell the truth."

"With respect," Herbert Allen interjected, "that's nonsense." Goizueta said, "Coke is a benign, paternalistic company often accused of being too generous with its employees."

"That may be your point of view, but it's not mine," Puttnam responded. Then he cut to the heart of Coke's self-perception. "I said something that was really dumb and was a killer. I said, You don't understand. I don't want to wake up in the morning, look in the shaving mirror, and ask myself, Does Don Keough like me today?" Today Puttnam recognizes these words were a turning point. "I knew that was a mistake immediately. I saw the hurt look in Keough's eyes."

What Puttnam was struggling with was corporate doublespeak. Theoretical pledges to back Puttnam in trouble had turned into Herbert Allen's surrogate father, Ray Stark, fuming about his scripts' being rejected and a stalemate on Ghostbusters II. But the clincher was Bill Cosby. Coke's spokesman made it very clear he was unhappy with Puttnam's failure to stroke him sufficiently on Leonard Part 6, and to remove the producer, Alan Marshall (see box, page 100). Cosby had told Coke, "Puttnam can't run the studio—he's killing it," and walked to Warner Bros, with his next picture—a loss of face not only for Coke but also for Cosby's golfing partner Don Keough. As if these problems were not enough, Puttnam sensed a sinister undertow. Something else was brewing. And had been, if only he'd known it, even at the time he was hired.

For all his aura of fastidious reflection, Goizueta is a gambler, swift and opportunistic, with his eye always on the Quotron machine pumping out stock prices. From the moment he became chairman in 1981, he had shown he was not content to run a soft-drink business that might grow by 10 percent a year. He wanted to build a glittering conglomerate. He bought out the bottlers in an ingenious maneuver with public money and took radical risks with the drink business. He staked Coke's name on a diet cola. He even abandoned the magic formula. He took Coke into a pasta business (and out), into wine (and out), and into show business (and partly out). He did it with brilliant financial capework and by borrowing and borrowing on a scale that would have shaken his patron, Coke's old man, Woodruff. A month after the July board meeting, Goizueta was secretly busy on some more spectacular balance-sheet work, and the vibes gave Puttnam a chill of unease. Preparing to fly to Montreal for a lunch in honor of Garth Drabinsky of Cineplex Odeon, Puttnam asked Valerie Kemp to call Don Keough, who was also attending, and set up a meeting there. Keough did not return the call and though genial at lunch did not seek him out to say good-bye. Dick Gallup of Columbia pretended not to see him. In this ominous atmosphere, Puttnam was surprised by a call from the perennially opaque Herbert Allen, who said he liked Someone to Watch over Me.

On September 1, Puttnam was awakened at five A.M. by his lawyer in New York, Tom Lewyn. "Have you heard the announcement?" he asked. Lewyn relayed to Puttnam the press announcement of a merger of Columbia Pictures with Tri-Star, a dramatic move that took the losses of Ishtar and other unforeseen turkeys from Coca-Cola's balance sheet. It also catapulted Tri-Star's Victor Kaufman, a bright lawyer, into Fay Vincent's job as head of the new company, Columbia Pictures Entertainment.

Only a small inner circle had known, arguably because of the dangers of insider trading. The head of Human Relations at Coke read it in the paper along with everybody else. Fay Vincent found himself swept into Siberia on the tax-audit floor in Coca-Cola's New York building. The reports said that Goizueta and Keough were going to spend ten minutes with each of their executives to explain the repercussions. On September 3 they flew to L.A. with Vincent and invited Puttnam to the Bel-Air hotel to reassure him that nothing had changed. But Puttnam's preference for the written word suddenly became relevant. His contract specified that he reported only to Vincent, and now he was being asked to report to Victor Kaufman. Puttnam's lawyer, Tom Lewyn, felt that Coca-Cola had broken Puttnam's contract. Keough reassured him there would be minimal staff changes and suggested he work something out with Kaufman.

Puttnam went back to the studio with Coke's reassurances ringing in his ears but with the press reporting that he was out. Hurt and confused, he wrote to Keough the next day to ask for help in dealing with the press and alleviating the fears and anxiety among "a spectacular group of people." He said, "People here at the studio trust me, and they're able to trust me because I trust the Coca-Cola Company." Keough did not reply. Puttnam's confusion was increased by the loss of Father Vincent to turn to. The Saint was philosophical about his own removal. "When matters of faith conflict with matters of finance," he told me, "finance always wins."

On September 11, Puttnam had a onehour meeting with Kaufman in his office in New York. Puttnam told him, "I know you can't live with my existing contract, but I'll continue if you give me a smaller stockade with higher walls," i.e., a ceiling of $23 million instead of $30 million before he sought spending approval. According to Puttnam, Kaufman answered that they were about to prepare a public offering of stock in the new company, and could not have a C.E.O. with only eighteen months to run and this kind of autonomy. Even more to the point for Puttnam was Kaufman's declared policy of going back to package deals and big stars, as he had with Rambo. Puttnam told Kaufman he would resign. Kaufman said, "You won't be writing any more letters, will you? Don Keough was irritated that you wrote to him about his promises concerning the staff. He felt you overstated the case." A few days later Puttnam told a stricken staff at the end of his final Reel Truth seminar that he'd decided to quit. Victor Kaufman, he said recklessly, had pledged "there will be no changes in the foreseeable future and all executives will get the opportunity to prove their worth."

On his last night as head of Columbia, Puttnam took Patsy to see the Cirque du Soleil, where they watched a man on a tightrope who didn't fall off. "Just think," said Patsy. "He's risking his life, and he's being paid ten bob and a toffee apple." Puttnam's $5 million compensation from Coke was more than that. It gave him plenty of time to look around. He and Patsy went to Thailand to see the hill country, and bought a slice of Thai beach. By February he had a $50 million international fund for making movies, and he was starting to roll again. The last time I saw him in New York he was off to Washington to meet Jim Brady, Reagan's gallant press officer, who had taken a bullet in the head in the attempted assassination. Puttnam had bought his story and had the idea of asking Robert Bolt to write it. Bolt had suffered a stroke that left him, for a time, with incapacities identical to Brady's. "I've been looking for ages for a story that would use Bolt's experience without it being his own story, transferring his feelings to Brady." He laughed happily. "That's good producing!" He called the next day to say that when he and Bolt sat down with Jim Brady for lunch at the White House, they were joined by another old Hollywood player, President Reagan.

Shortly after Puttnam's resignation, Gomorrah was visited by an earthquake. Puttnam was working out his three months' notice, but rather than sit in his office and watch his team get fired—as they were, one by one, in spite of Coke's pledges about the staff—he chose to fulfill film-festival commitments in Tokyo. The pictures on his office wall were left eerily askew after the quake, and the effect was as if a bomb had been dropped on the accumulated ethic of his life. Hanging crooked on the wall were: the 77m^-magazine cover on John Lennon's death with the headline "When the Music Died"; a watercolor of his Wiltshire house; a snap of the young Patsy; a newspaper cutting of the death of Elvis Presley; a quote from Flaubert, "Be regular and ordinary in your life, like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work"; and, facing his desk, a photograph of a Cambodian refugee-camp baby with hopeless eyes taken during his making of The Killing Fields. "To remind me," he said, "of the outside world."

Today, Dawn Steel sits in that comer office with a gilded gobbler behind her bearing the slogan "Oh Lord, please don't let me make any turkeys." Her first major project as head of Columbia is The Way We Are, number one on a slate of eight new Ray Stark productions. Ghostbusters II, starring Bill Murray and Dan Aykroyd, and written by Aykroyd and Harold Ramis, is about to go into preproduction.

Two Puttnam projects, The Last Emper or and Hope and Glory, were nominated for Best Picture in this year's Oscars, and both Bertolucci and Boorman were also nominated for Best Director. It was ironic for Bertolucci since, after Puttnam's departure, Columbia had all but dumped his movie—and its decision to withhold The Last Emperor from more than 150 theaters had triggered a business war between it and Cineplex Odeon, one of North America's largest movie-theater chains. Cineplex chairman Garth Drabinsky retaliated by refusing to show Leonard Part 6, and is no longer on speaking terms with Victor Kaufman. Nonetheless, Kaufman discovered in himself a great personal interest in The Last Emperor when it was chosen to get a royal premiere in Britain, attended by Prince Charles and Princess Di. He took a posse of CocaCola executives along for the ride. No one from Columbia or Coca-Cola, however, was at the Beverly Hills Hotel on February 9 for a movie-industry lunch. Puttnam was there to receive an Eastman Kodak Second Century Award, given to filmmakers who have encouraged new talent.

Patsy reflected, "David is much more Liddell now than he used to be. I know now he'll never slip back.''

Abrahams lost the race for Great Britain, but Liddell won the race for his life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now