Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE GREEN HOUSE

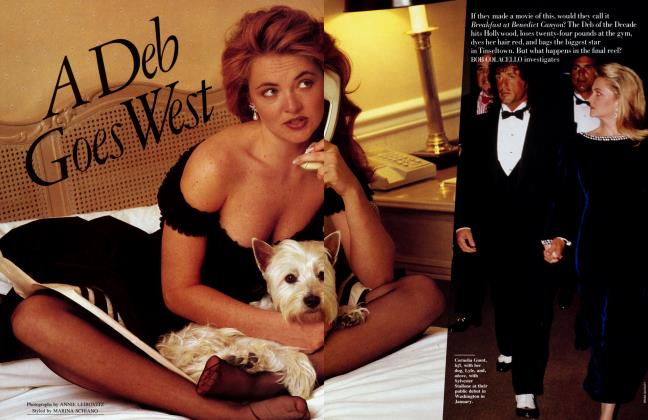

Within the walls of colonial Cartagena. Sam Green has created an exotie private world. His reconditioned grandee's palace is inhabited by tropical animals and visited by everyone from Yoko Ono to Greta Garbo. STEVEN M. L. ARONSON packs his toothbrush

"Garbo walked all over that city—the biggest star ever to come to South America—and nobody recognized her."

At the sizzling northern tip of South America, four hours and twenty minutes from Manhattan, on the historic harbor which shipped the Inca gold that gilded Spain, in the antique city of Cartagena, Colombia, a New York art entrepreneur and self-described social worker (he specializes in the rich) entertains a flood tide of workaday jet-setters—Niarchoses, Agnellis, Rothschilds, practically every Kennedy of the younger generation.. .and the century's most determined recluse, Greta Garbo.

It took a gringo to put Cartagena, once the treasure city of Spain's New World, back on the map. In 1972 the thirty-twoyear-old Samuel Adams Green was on his way to explore ancient sculpture sites in the interior when his plane touched down in Cartagena. Wandering the streets, he "discovered" a whole colonial world: cathedrals, palaces of the Inquisition, grand plazas, and mighty fortifications, all intact. Outside the city walls, to be sure, the seamy business of twentieth-century resort life throbbed on with discos, casinos, and a Hilton, not to mention cocaine dealing on an immoderate scale. Inside the ramparts, however, the city was a tropical Seville, its Castilian calm broken only by the clatter of horse-drawn carriages.

On Calle Santo Domingo the balconies of monumental sixteenthand seventeenth-century houses leaned out, each to each, across a narrow channel of street. "I had my choice of bedraggled palaces," Green says. The door to one casa senorial opened on cloistered courtyards, expansive arches, massive stone pillars, five hundred balustrades, and the grandest of grand salons—eighty feet long, forty feet wide, with a forty-foot-high mahogany ceiling.

For all that, there was a single outhouse, and everywhere Green looked excruciating squalor stained the splendor. Intent on proving Marcus Aurelius's witticism that even in a palace life can be lived well, he bought the colossus. There are fourteen bathrooms now. Restoration took five years, forty laborers working full-time. "I would bring down electric tools," he says, "but the carpenters felt more comfortable sawing the rock-hard mahogany floorboards by hand the way their ancestors had."

Now, furniture. Cartagena was bare—"not a stick of period furniture," Green says. "Hollywood was being built at about the same time the Panama Canal opened, and Cartagena was suddenly accessible to decorators looking for antiques and accoutrements for Spanish-hacienda movie-mogul homes." Luckily for Casa Green, South American pieces had become unfashionable and were available inexpensively at auction. A trove of eighteenth-century beds, tables, chests, sofas, mirrors, chandeliers and candelabra, crucifixes and paintings, even a working pipe organ, was repatriated to Colombia. Before moving in, Green expediently hired the local witch, or bruja, to place a ceremonial protection on the house. "Miss Lina in 1975 was somewhere between seventy and seven hundred years old," he says. "She was pitch-black with piercing blue eyes and almost as tall as Wilt the Stilt. She had two teeth, one on top and one on the bottom, and she spoke Elizabethan pirate English. She was a character." Green bought the biggest display he could—10,000 pesos' worth of smoke and incantation. "What I was really buying was security," he explains. "Miss Lina was a sort of local burglar alarm, hexing potential thieves."

Back in New York, Green dined out on tales of the bruja's brouhaha. His friend Yoko Ono took them seriously, however, and insisted, "I've got to meet this woman." She flew to Cartagena to engage Miss Lina for her own purposes, installing herself in the unfinished house. "Yoko paid Miss Lina 60,000—whether pesos or dollars is still unclear—for the full treatment," Green reports, "a three-day hocus-pocus including powders, murky potions, and the sacrifice of a white dove."

By Christmas 1977 the house was ready. Green's first guest was his Rich Cousin, legendary host Henry Mcllhenny of Philadelphia. "I was aspiring to a Poor Cousin's version of Henry's castle in Ireland, which had forty servants and 30,000 acres," Green confesses. Next came Cecil Beaton on a convalescent visit after his crippling stroke (he sketched some surprisingly facile watercolors in the guest book with his left hand); art historian John Richardson; and Sandra Pay son (then Lady Weidenfeld). By now the casa boasted two butlers, a laundress, a maid, a secretary, a gardener, and a cook called Bernardino on whom the demands have been extraordinary. One house party included both a lady astrologer who wouldn't eat anything that had ever had eyes (excluding potatoes) and a Mr. Black Universe who required six steaks a day.

There are two monkeys in the cobbled forecourt. There are also two raucous macaws and two profane parrots that have absorbed so much chitchat they can make the noise of forty cackling, guffawing, gossiping guests. Finally Green shouts "Shut up!" from his perch, across the patio; the parrots squawk back "Shut up!" and cacophony ensues. Completing the menagerie is a pet perezoso, or sloth, affectionately called Liza by frequent houseguest Peter Allen.

Life is informal in Cartagena. Invited for a week, I was told to bring only a bathing suit, shorts, and a toothbrush. You're up by eight. By ten, in the bright cool heat, you're on a motor launch headed for the nearby Rosario Islands to snorkel and scuba-dive among the reefs. At midday, natives in dugouts row up with live lobsters, which are cooked on the white sandy beach in the shade of a palm tree. Afterward you lie supine through the breathless afternoon. "The slavery of the watch is gone," says filmmaker Franco Rossellini, often a houseguest. Spanish hours are kept at Casa Green—you dine till midnight. Then a final swim in the pool and you take your lobster-livid limbs and shrimp-filled stomach to bed.

Unless you are Greta Garbo and, wanting to be alone, are already in bed. "Unwittingly, she came down during the Cartagena Film Festival," Green recounts, "and the most astonishing thing is that Garbo walked all over that city—the biggest movie star ever to come to South America—and with every show-biz reporter in the Spanish-speaking world there, nobody recognized her. ' '

How exactly did she spend her day? "She's a health nut," says Green. "Yoga before breakfast, then a walk, then laps in the pool, then another walk, then she knocked back her Bees' Knees—that's a drink I make with honey and lime juice and the local rum, which is delicious. Lunch. Then more exercise, more walks, another Bees' Knees. Dinner. And early to bed and wait for the sandman—like every day of her life."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now