Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBREAST BARING

PHILIP ROTH

Novelist Philip Roth and the painter Philip Guston shared a fascination with the "crapola" of modern life

Books I

"One time, in Woodstock," Ross Feld said, "I stood next to Guston in front of some of these canvases. I hadn't seen them before; I didn't really know what to say. For a time, then, there was silence. After a while, Guston took his thumbnail away from his teeth and said, 'People, you know, complain that it's horrifying. As if it's a picnic for me, who has to come in here every day and see them first thing. But what's the alternative? I'm trying to see how much I can stand.' "

—From Night Studio: A Memoir of Philip Guston, by Musa Mayer

In 1967, sick of life in the New York art world, Philip Guston left his Manhattan studio forever and took up permanent residence with his wife, Musa, in their Woodstock house on Maverick Road, where they had been living on and off for some twenty years. Two years later, I too turned my back on New York to hide out in a small furnished house in Woodstock, across town from Philip, whom I didn't know at the time. I was fleeing the publication of Portnoy's Complaint. I was no puritan, but my overnight notoriety as a sexual freak had become too difficult to evade in Manhattan, and so, with the book at the top of the best-seller list,

I decided to clear out—first for Yaddo, the secluded artists' colony in upstate New York where, for three months, I tried in vain to focus on a new novel, and then, beginning in the spring of 1969, for that small rented house tucked out of sight midway up a meadow several miles from Woodstock's main street. I lived there with a young woman who was just finishing a Ph.D. in comparative religion and who for several years had been renting a tiny cabin, heated by a wood stove, in the mountainside colony of Byrdcliffe, which some decades earlier had been a primitive hamlet of Woodstock artists. During the day, while I wrote on a table in the upstairs spare bedroom, she went off to the cabin to be alone and work on her dissertation.

A life in the country with an attractive and clever young religion student was anything but freakish, and it provided a combination of serene social seclusion and robust physical pleasure that, given the illogic of creation, led me to write, over a four-year period, a cluster of uncharacteristically freakish books. My expanding reputation as a madman crazed by his penis was precisely what instigated the fantasy at the heart of The Breast, a book about a college professor who turns into a female breast; it had something to do as well with inspiring the farcical legend of homeless alienation in homespun America that evolved into my baseball book, The Great American Novel. The more simplehearted and natural my Woodstock satisfactions, the more tempted I was in my work by the excesses of the Grand Guignol. I'd never felt more imaginatively polymorphous than when I would put two deck chairs on the lawn at the end of the day and we'd stretch out to enjoy the twilight view, I with a glass of Jack Daniel's in my hand and the teetotaling religion student with her evening Coke. Looking securely toward the southern foothills of the Catskills, I liked to think of them as unpassable Alps through which no disconcerting irrelevancy could pass. I felt refractory and unreachable and freewheeling, and I was dedicated—perversely overdedicated, perhaps—to shaking off the vast newfound audience whose collective fantasies were not without their own transforming power. As it happened, I shook that audience off all too well. What I wrote during this long transalpine expatriation—Our Gang, The Great American Novel, and The Breast—did the job just fine and, for good or bad, my hubris was rewarded with its just deserts: never again did any of my books have even one-tenth as many readers as Portnoy's Complaint.

Guston's situation in 1969—the year we met—was very different from mine. At fifty-six, he was twenty years older than I and full of the doubts and uncertainties that can beset an artist of consequence in late middle age. He felt that he'd exhausted the means that previously had unlocked him as an abstract painter, and he was bored and disgusted by the skills that had gained him renown. He didn't want to paint like that ever again; some days he even tried to convince himself that he shouldn't paint at all. But since nothing but painting could contain his emotional turbulence, let alone begin to deplete his self-mythologizing monomania, renouncing painting would have been tantamount to committing suicide or, at the very least, have meant burying himself alive in that coffin clinically described as depression. Although painting monopolized just enough of his personal despair and his seismic moodiness to make the intense anxiety of being himself something even he could sometimes laugh at, it never neutralized the nightmares entirely.

My expanding reputation as a madman crazed by his penis was precisely what instigated the fantasy at the heart of The Breast.

It wasn't intended to. The nightmares were his not to dissipate with paint but, during the ten years before his death in 1980, to intensify with paint, to paint into nightmares that were imperishable and never before incarnated in such trashy props. That terror may be all the more bewildering when it is steeped in farce we know from what we ourselves dream but, probably best of all, from what has been dreamed by Beckett and Kafka. Philip's discovery— akin to theirs, and driven by a delight in mundane objects as boldly distended and bluntly de-poeticized as theirs—was of the dread that emanates from the most commonplace appurtenances of the world of utter stupidity. The unexalted vision of everyday things that newspaper cartoon strips had impressed upon his imagination when he was growing up in an immigrant Jewish family in California, the American crumminess for which, even in the heyday of his thoughtful lyricism, he always had an intellectual's soft spot, he came to contemplate—in an exercise familiar to lovers of Molloy and Malone Dies as well as The Castle—as though his life, both as an artist and as a man, depended on it. And it did. This popular imagery of a shallow reality Philip imbued with such a weight of personal sorrow and artistic urgency as to shape in painting a new American landscape of terror.

Cut off from New York and living apart from Woodstock's local society of artists, with whom he had little in common, Philip oftentimes felt neglected, out of it, undervalued, isolated, resentful, uninfluential, misplaced. It wasn't the first time that his ruthless focus on his own imperatives had induced a black mood of alienation, nor was he the first American artist embittered by that syndrome. It was as common among the very best as it was among the plodding, the middling, and the very worst—only with the very best it was not necessarily a puerile self-drama concocted out of touchiness and egomaniacal delusions. In many ways it was a perfectly justified response for those, like Guston, whose brooding, brainy, hypercritical scrutiny of their every last aesthetic choice is routinely travestied by the misjudgments and simplifications that support a major reputation.

Philip and his gloom were not inseparable, however. In the company of the few friends he enjoyed and was willing to see, he could be the most cordial, unharried host, exuding a captivating spiritual buoyancy unmarked by his anguish. In his physical bearing too there was a nimble grace that was touchingly at variance with the bulky torso of the heavydrinking, somewhat august-looking, white-haired personage into whom darkly, Jewishly, Don Juanishly handsome Guston had been transformed in his fifties. At dinner, wearing those baggybottomed, low-slung khaki trousers of his, with a white cotton shirt open over his burly chest and the sleeves still turned up from working in the studio, he looked like the Old Guard Israeli politicians in whom the imperiousness and the informality spring from an unassailable core of self-belief. It was impossible around the Guston dining table, sharing the rich pasta that Philip had cooked up with a display of jovial expertise, to detect any sign of the self-flagellating component within his prodigious endowment of self-belief. Only in his eyes might you be able to gauge the toll of the wearing oscillation—from iron resolve through rapturous equilibrium to suicidal hopelessness—that underlay an ordinary day in the studio.

What caused our friendship to flourish is what usually is necessary to solidify a friendship between writers or artists. There was, to begin with, a similar intellectual outlook and a love for many of the same books, as well as a delight we happened to share in what Guston called "crapola," starting with billboards, garages, diners, burger joints, junk shops, auto body shops—all the roadside stuff that we occasionally set out to Kingston to enjoy—and extending from the flat-footed straight talk of the Catskill citizenry to the Uriah Heepisms and Tartuffisms of our perspiring president. What sealed the camaraderie was that we liked each other's new work. The differences in our personal lives and our professional fortunes did not obscure the coincidence of our having recently undertaken comparable self-critiques: quite independently, impelled by very different dilemmas, each of us had begun to consider crapola not only as a curious subject with strong suggestive powers to which we had a native affiliation but as potentially a tool in itself, a blunt aesthetic instrument providing access to a kind of representation free of the complexity we were accustomed to valuing. What this tactlessness or tastelessness or, more precisely, selfsubversion might be made to yield was anybody's guess, and premonitions of failure couldn't be entirely curbed by the liberating feelings that an artistic aboutface usually inspires, at least in the early stages of not quite knowing what you are doing.

Nonetheless, at just about the time that I began not quite to know what I was doing exulting in Nixon's lies, or traveling up to Cooperstown's Hall of Fame to immerse myself in baseball lore, or taking seriously the idea of turning a man like myself into a breast—and reading up on endocrinology and mammary glands—Philip was beginning not quite to know what he was doing hanging cartoon light bulbs over the pointed hoods of slit-eyed, cigar-smoking Klansmen painting self-portraits in hideaways cluttered with shoes and clocks and steam irons of the sort that Mutt and Jeff would have felt at home with.

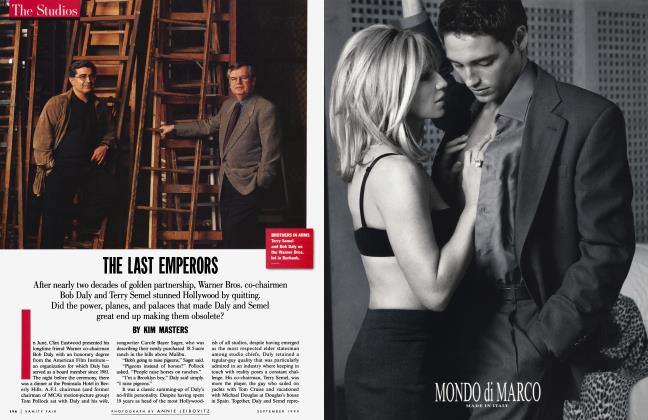

Philip's illustrations of incidents in The Breast, drawn on ordinary typing paper, were presented to me one evening at dinner, shortly after the book's publication. A couple of years earlier, while I was writing Our Gang, Philip had responded to the chapters that I showed him in manuscript with a wonderful series of caricatures of Nixon, Kissinger, Agnew, and John Mitchell. He worked on these caricatures with considerably more concentration than he did on the drawings for The Breast, and for a moment he even toyed with the thought of publishing them as a collection under the title Poor Richard. The drawings inspired by The Breast were simply a spontaneous rejoinder to something he'd liked—another friend might have sent a box of cigars. The drawings were intended to do nothing other than please me, and they did.

For me his blubbery cartoon rendering of the breast into which Professor David Kepesh is inexplicably transformed—his vision of the afflicted Kepesh as a beached mammary groping for contact through a nipple that is an unostentatious amalgam of lumpish, dumb penis and inquisitive nose—managed to encapsulate all the loneliness of Kepesh's humiliation while at the same time adhering to the mordant comic perspective with which Kepesh tries to view his horrible metamorphosis. Though these drawings were no more than a pleasant diversion for Philip, his predilection for the self-satirization of personal misery (the same strategy for effacing the romance of self-pity that stuns us in great comic stories of suffering like Gogol's "Diary of a Madman'' and "The Nose") as strongly determines the image here as it does in those paintings where his own tiresome addictions and sad renunciations are represented by whiskey bottles and cigarette butts and lonely insomniacs epically cartoonized. He may have been only playing around in those drawings, but what he was playing with was the point of view with which he had set about in his studio to overturn his history as a painter and to depict, without rhetorical hedging, the facts of his anxiety as a man. Coincidentally, Philip represents himself in his last paintings as someone who has also endured a grotesque transformation—not, however, into a thinking, dismembered sexual gland but into a bloated, Cyclopsian, brutish head that has itself been cut loose from the body of its sex.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now