Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowGUPPIE FICTION

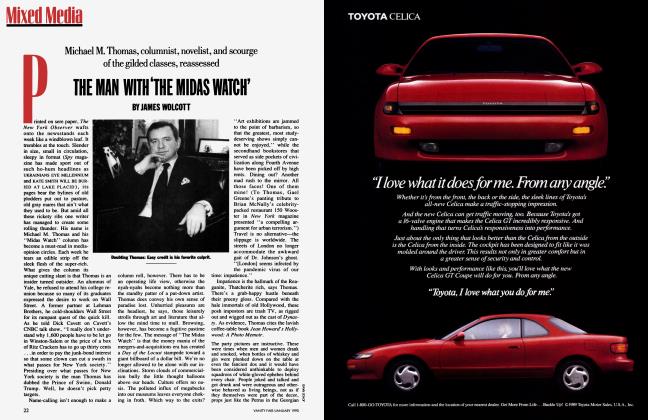

Mixed Media

Gay yuppies and the suburban idyll of David Leavitt

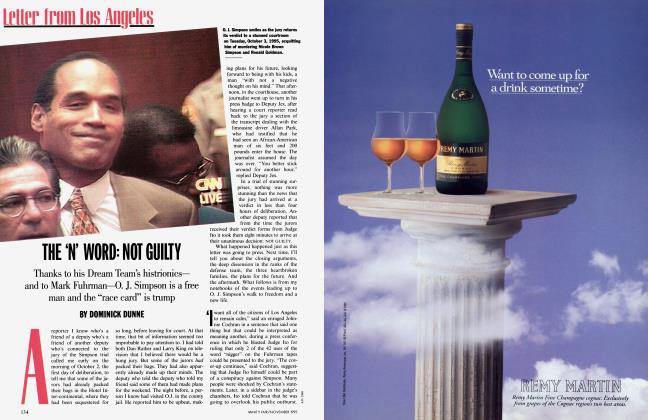

JAMES WOLCOTT

Gay fiction has hung up its G-string. Gone are the days when a John Rechy hero would flex a biceps to feed a fistful of vitamins into his mouth, fortifying himself for a night on the manprowl. The glory holes have been plugged. Kinky is out, kindness is in. Perhaps the writer who best reflects this shift from sexual outlaw to Care Bear is David Leavitt, the wavyhaired boy wonder who won rave notices for his first collection of stories, Family Dancing, tender autopsies of cancer and swollen woe. Family Dancing was followed by the novel The Lost Language of Cranes, which failed to lift the critics out of their seats. The favorable reviews were subdued, the unfavorable ones downright squeamish. "My first experience with vicious homophobia was with the publication of The Lost Language of Cranes," Leavitt told an interviewer. "They were saying, 'This is a gay book, and that's all it is.' "

Even so, Leavitt has managed to emerge as a mouthpiece for a rising generation of writers, gay and straight. He wrote an essay for The New York Times Book Review praising such surgical blades of the hairline-fracture school of precarious selfhood as Marian Thurm, Amy Hempel, Meg Wolitzer, and Peter Cameron. He also edited a special issue of the Mississippi Review called ' 'These Young People Today," which showcased a lot of the same crew. His ambitious overview of "The New Lost Generation" in Esquire intensified the cliquish note. Of his intimate circle, he wrote, "Like the folks in Mary's newsroom or the crew of the Enterprise bridge, we are a gang." A smug, pushy gang. "We walk five abreast, arm-inarm, so that other people must veer into the street to avoid hitting us." Linking them as they crowd the sidewalk is a common belief bom of self-certitude. "We trust ourselves, and money. Period." Outta the way, nonentities! Step aside, deadbeats! It's shoe leather we're burning now.

Leavitt's trust in money has not been misplaced. Despite the lukewarm response to The Lost Language of Cranes, his diabolical agent, Andrew Wylie, secured a fab sum for Leavitt's new novel, Equal Affections (Weidenfeld & Nicolson). Care Bear is clearly too cuddly an image for someone with Leavitt's cool knack for success. "We trust ourselves, and money" could have been coined only in the mind of a yuppie.

David Leavitt is a gay yuppie: a guppie. He shares a house on Long Island with his lover, life partner, spousal equivalent, and significant other, Gary Glickman, an author too. Their books harmonize. Glickman's novel, Years from Now, covers the same phase of their courtship as Leavitt's Lost Language of Cranes. The chummy overlap of their fiction recalls the fraternizing of the Auden-Spender-Isherwood set. But where Auden and company had an itch for foreign adventure, Leavitt and Glickman heed a homing instinct. Former dabblers "in the great, cold, clammy river of promiscuity," Danny and Walter, the Leavitt and Glickman couple in Equal Affections, are content to stay put where it's warm and dry. Earlier generations may have ridden the wild surf. Nesters like Danny and Walter hole up in a wired cocoon.

Now they lived through machines, they were addicted to machines. They owned two nineteen-inch color television sets; two wireless remote-control VCRs; a Japanese stereo system with separate graphic equalizer and compact disk player; many compact disks (luminous arcs that still amazed Danny to look at); two sleek computers, each with a modem and printer; many kinds of software; a telephone that answered itself and redirected calls to other numbers; three air conditioners; a Cuisinart; a microwave oven; a can opener hinged to the bottom of the cabinet; a fancy German toaster; a coffeemaker that knew how to turn itself on at a prearranged time; a waterpick; a garage door opener.

What, no waffle iron? But don't make the mistake, O ye of little faith, of thinking that living in an appliance warehouse is an apolitical act. As Danny's sister, April, says, "Sometimes I think the most political thing a gay man or woman can do is to live openly with another gay man or woman." Norman Mailer onge identified one strain of feminism as girls-may-hold-hands-in-the-suburbs.

Gay lib in Equal Affections boils down to boys-may-hold-hands-in-the-suburbs. "The doors finally opened, and in the main waiting room Walter took Danny's hand; he turned; they hugged. A middleaged nurse, walking by, said, 'Really, couldn't you be more discreet?' " Understandably p.o.'d, Walter chases the nurse down the hall and ascertains her name. "He turned, started walking away, before announcing to the lobby at large, 'Please be aware that Nurse Mary Jenkins is a bigot.' "

Nurse Mary Jenkins is coughed up in the novel like a fur ball to appease those gay readers who might find Danny and Walter too quiescent, April's tribute notwithstanding. Yet the desire for placid peace behind a white picket fence runs deep. A gay version of that nice young couple down the block, they catch flak when they venture out of their hassle-free zone. No wonder they opt to cocoon. The Leavitt-Glickman family plan isn't without casualties. To make room for the gay father and lesbian mother, it's the traditional mom who's given the shove. Leavitt doesn't do this sadistically. Firm ground becomes shifting quicksand for the women in "Danny in Transit" and The Lost Language of Cranes who learn that their husbands are homosexual; they're poignant figures. In Equal Affections, the traditional mom is given the full tragic treatment. From the very first page Danny's mother, Louise, is under diagnosis, and her role in the novel is one long dying arc. Hers is a hard life. Her son is a homosexual. Her daughter is a folksinger. Her husband has a tootsie on the side. Presumably it is Louise's marathon dance with death that made Equal Affections such a hot publishing property. (Unlikely Weidenfeld & Nicolson would have wagered a fat wad of money on a book about two men sitting with their pants around their ankles talking about big hoes and low swinging balls.) Written on a weeping violin, the deathbed scenes in the bum unit are an all-out assault on the tear ducts, with Louise using her last losing strength to draw for Danny a jagged heart—symbol of her difficult love—and Academy Award performances from the entire cast. For those who cry easily, Equal Affections is a Terms of Endearment sobfest. And when April tells Danny that if she has a daughter she's going to name it Louise, in memory of their dead mother, it's both another cue to cry and a sign that out of death comes new life, cyclical rebirth. This refertilizing would be more like a spin on the great wheel of life if one weren't so aware of Leavitt's hand on the board manipulating the action. His stealth as a writer is that his writing is always so muted and removed—so "sensitive."

Timidity is Leavitt's biggest limitation as a writer. He needs to trim his eyelashes.

So what was it really like, their living together?

Danny and Walter are sitting in the living room on a Sunday afternoon, their pants around their ankles, having just watched Bigger in Texas on the VCR.

"Which of us is the man?'' Walter asks casually.

Danny looks across the sofa at him. "Well,'' he says, "I suppose you're the man because you go to work every morning in the city."

"But you go to the city every morning too!" Walter says. "And you put in those three-pronged outlets. With your screwdrivers and wrenches and drills." He looks satisfied.

"I also do the dishes, wash the sheets, and make the beds. You take care of the garden."

"Yes. With a big hoe."

"You like boys with hairless chests and tight buttocks," Danny says, "and I like big hairy men with low swinging balls. Besides, I cook."

"You fuck me," Walter says.

Danny is quiet for a moment, trying to think of a retort to that seemingly definitive fact. "I stayed home all day last Monday and talked to your mother about Debbie Klinger's divorce," he says finally.

"Well, then, I guess you are the woman," Walter says.

I'm the mommy. No, I'm the mommy. Adult voice: Well, you can't both be the mommy. 'Course, the hitch for male guppies is that neither one of them can be the mommy. Affections may be equal, but biology isn't—it's asymmetrical. Women can bear children, men can't. And two men sharing the same foxhole doesn't add up to much of a future, family wise. To outflank this seemingly definitive fact, Leavitt and Glickman have formulated a new family plan. The blueprint for this postnuclear unit consists of a gay father, a lesbian mother, and a child spawned, if need be, via artificial insemination. A neocon nightmare on six legs!

The gay father is a familiar figure in Leavitt's fiction. Family Dancing's "Danny in Transit" involved a gay father leaving the family for a lover. The Lost Language of Cranes concerned a gay man named Philip whose father comes out of the closet. Speculating about a gay father becomes a way of flirting with the incest taboo. The Lost Language of Cranes ends with Philip's father sleeping on Philip's floor, his white ankles shining in the moonlight. For all the pathos of the situation, it has the air of a nocturnal pastoral. Men together in the big night. But men together can't create babies. For gay men of Philip's father's generation, reproducing required living a life that was something of a lie. It meant marrying and pretending to be straight, until the pretense became insupportable. For gay men of Philip's generation, being out of the closet means not having to lie, not having to wall oneself within a mummified marriage. But one still needs a willing woman to supply a womb. How can the blueprint of gay father/lesbian mother be brought to fruition? This is where Leavitt and Glickman get tricky.

Very tricky. In Glickman's Years from Now, two guppies, David and Andrew, face off about David's desire to father a child via his lesbian friend Beth. "Andrew, why not?" David asks. "It's the only way I can think of, at the moment. I mean, we could splice our genes, I guess, and try one of those peritoneal pregnancies. I'd have your baby, if you want..." Sorry, David, you haven't got the shelf space. David eventually does the deed with Beth and becomes a daddy. Equal Affections dispenses with the old in-and-out altogether. The lesbian mom in Equal Affections is Danny's sister, April, a human herald of spring: "It is still March. Twenty-two days before the month begins during which the whole world will fill with her name." If that weren't bad enough, April (the person, not the month) is a folkie in the Holly Near fashion, hauling a hefty protest bag of what Bob Dylan used to call fingerpointing songs. When she writes her brother, "Have written a new song about Winnie Mandela which I think is pretty good," you know you'd rather be struck deaf than hear it. April has a hetero history of which she is not proud. "It's not a period of my life I look on fondly, full as it was of penises." Coming to the rescue is a gay man named Tom Neibauer. "You remember Tom Neibauer? Tall, good-looking, with a beard? He does computer music and has a deaf Chinese lover?" Oh, him. Well, Tom has a solution that allows April to bypass icky contact with the male member. He masturbates into a cup, brings the cup-o'-spurt over to the house, whereupon April's girlfriends insert the fixings in her with—a turkey baster. After much delay, the diddling takes hold and, wah-la, April is abloom. Her Earth Mother status is ensured. "The best part is, being pregnant has made me more creative than I've ever been. My breasts pour out milk, my guitar pours out notes." Pretty scary, isn't it?

Yet there's more tension between the sexes in Leavitt's fiction than he's willing to own up to. It's the women in Equal Affections who have the hysterics. A distraught Louise chases her husband out into traffic barefoot; April nearly miscarries after she stupidly twirls around in mad circles and lands plop on the asphalt. But there's a deeper battle in Leavitt's work, between women's messy natures ("Emotions, in her case, usually expressed themselves in a digestive or respiratory manner") and men's rooted stems. He homoeroticizes Louise's few remaining moments on earth by visiting her with a spectral vision of one of her former heartthrobs: "Blond, muscled Tommy Burns, naked as the day he was born, his penis hard, with his smell of grease and deodorant." And near the end of the novel, Danny and a ballooningly pregnant April stroll along the beach, with Danny on the lookout for a local landmark. There's this guy, he tells April, who lounges at the beach in a skinny brief housing a "positively huge" erection. Old ladies, young moms, rugged boys, they all stop and stare at this daylong hotdog. Although Leavitt pays homage to women's wombs, those incubators of the new gay family, his primary allegiance is to the proud hard cock that seems to exist solely for itself. It's the pole up which he runs his flag. The funny thing about Leavitt is that he seems almost unconscious of his intent. A casual reader might think those hard-ons merely props. Leavitt hides his thought processes, even from himself. His fear of wornen is covert. He applies sexual politics with a turkey baster.

Timidity is Leavitt's biggest built-in limitation as a writer. Talent he has, abundantly. What he doesn't have is the gumption to get beyond certain sighing pieties about being gay. He needs to trim his eyelashes. In story after story, novel after novel, there arrives the moment when Leavitt's alter ego announces, "Mom, Dad, I'm gay." But once you've broken the news, and broken the news, it's no longer news. This leaves Leavitt with little to report save for slow news from the domestic front. Large chunks of Leavitt's fiction become the latest chapter of Life with Gary, just as large chunks of Glickman's fiction document Life with David. You can wring significance from only so many sunsets, sing so many variations of "Embraceable You."

It needn't be this way. Gay writers from Isherwood to Vidal have had constant companions in their private lives without allowing that to preclude a greedy thirst for gritty swigs of experience (and, in Isherwood's case, intimations of the holy in the gray ash of a hangover). So it isn't the gay element of being a guppie that holds Leavitt and Glickman back, it's the yuppie element, the protective coloration of being contented consumers. To them, being a guppie means not merely purchasing comfort but avoiding conflict. Fiction, however, is built upon conflict, upon contesting visions of what's true and what's good. Conflict avoidance explains why nothing sneaks up on the reader unawares in their books, why everything is prepared with a careful, cautious hush. To be a guppie is to be something of a control queen. A novel as beautifully alive as Isherwood's Down There on a Visit couldn't have been composed by a control queen—its expanse necessitated a mental and physical voyaging-out.

In an interview in The New York Times, Leavitt said that the life his character Philip wants in The Lost Language of Cranes is the life he himself has, "and [Leavitt] hopes it will last forever, 'God willing.' " God willing? God forbid. The strategic retreat David Leavitt has beaten to the suburbs may be bliss for him as a guppie, but it could be his death sentence as a writer. Glickman, likewise. If they're this spooked in youth, middle age may leave them petrified.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now