Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

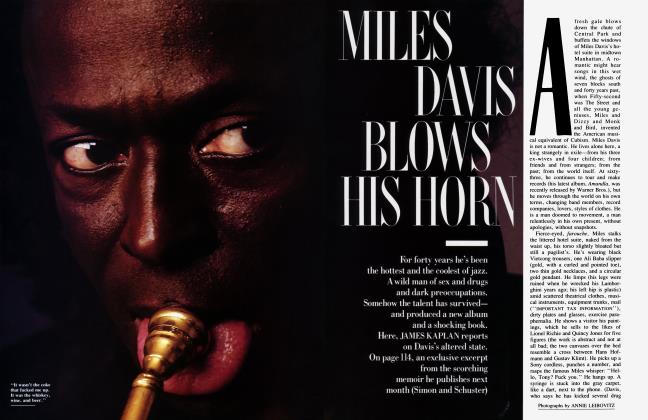

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFrom 1975 until early 1980 I didn’t pick up my horn once. I had been obsessed with it for thirty-seven straight years, and at forty-nine I needed a break, needed another perspective on everything I was doing in order to make a clean start.

My health was also a factor. I hated limping around the stage like I was, you know, being in all that pain and taking all them drugs. It was a drag. I couldn’t play two weeks in a club without having to go to the hospital. Drinking so much, snorting all the time, and fucking all night. You can’t do all of that and create music like you want to. You got to do one or the other. Artie Shaw told me one time, “Miles, you can’t play that third concert in the bed.” After a while, all that fucking ain’t nothing but tits and asses and pussy. After a while there is no emotion in it because I put so much emotion into my music.

The only reason I didn’t get staggering drunk was because when I played all that shit came out of my pores. I never did get drunk when I drank a lot, but I would throw up the next day at exactly twelve noon. Tony Williams would come by sometime in the morning and at 11:55 he would say, “O.K., Miles, you got exactly five minutes before it’s time for you to throw up.” And then he’d leave the room and I would go into the bathroom at exactly twelve and throw up.

Then there was the business side of the music industry, which is very tough and demanding and racist. I didn’t like the way I was being treated by Columbia and by people who owned the jazz clubs. They treat you like a slave because they’re giving you a little money, especially if you’re black. They treated all their white stars like they were kings or queens, and I just hated that shit, especially since they were stealing all their shit from black music and trying to act black. All the record companies were interested in at that time was making a lot of money and keeping their so-called black stars on the music plantation so that their white stars could just rip us off.

During those four or five years that I was out of music, I mostly just took a lot of cocaine (about $500 a day at one point) and fucked all the women I could get into my house. I was also addicted to pills, like Percodan, Seconal, and I was drinking a lot of Heinekens and cognac. Sometimes I would inject coke and heroin into my leg—it’s called a “speedball” and was what killed John Belushi.

I became a hermit, hardly ever going outside. My only connection with the outside world was through watching television—which was on around the clock—and reading newspapers and magazines. Sometimes I got information from a few old friends who would drop by to see me, to see if everything was all right, but sometimes I wouldn’t even let them come in. When I did, they would be shocked. But they didn’t say nothing, because I think they were afraid if they had, I would just put them out, which I would have. After a while many of my old musician friends stopped coming by. There were times during this period when I didn’t leave the house for six months or more.

When all those rumors got out about me doing a lot of drugs during that time they were all on the money, because I was. Sex and drugs took the place that music had occupied in my life until then, and I did both of them around the clock. I had so many different women during this period that I lost track of most of them and don’t even remember their names. They were there one night and gone the next day and that was that. Most of them are just a blur. Toward the end of my silent period, Cicely Tyson came back into my love life, although she had always been a friend.

I was interested in what some people would call kinky sex, you know, getting it on in bed sometimes with more than one woman. I enjoyed it, I ain’t going to lie about that. It gave me a thrill—and during this period I was definitely into thrills. Now, I know people reading this will probably think I hated women, or that I was crazy, or both. But I didn’t hate women; I loved them, probably too much. I loved being with them—and still do—doing what a lot of men secretly wish they could do with a whole lot of beautiful women. I was doing it in private and wasn’t hurting nobody else, and the women I was with loved it as much as or more than I did. I know what I’m talking about here is disapproved of in a country that is as sexually conservative as the United States. I know that most people will consider all of this a sin against God. But I don’t look at it that way. I was having a ball, and I don’t regret ever having done it. And I don’t have a guilty conscience, either. I would admit that taking all the cocaine that I was probably had something to do with it, because when you’re snorting good cocaine your sex drive needs satisfaction.

A lot of people thought I had lost my mind, or was real close to losing it. When I didn’t have coke my temper was real short and things would just get on my nerves. I couldn’t handle that. I didn’t listen to any music during this period. So I would snort coke, get tired of that because I wanted to go to sleep, then take a sleeping pill. Then I didn’t want to go to sleep, so I’d go out at four A.M. and prowl the streets like a werewolf, or Dracula. I’d go to an after-hours joint, snort more coke, get tired of all the simple motherfuckers who hang out in those joints. So I’d leave, come home with a bitch, snort some, take a sleeping pill.

All I was doing was bouncing up and down. That was four people, because being a Gemini I’m already two. Two people without the coke and two more with the coke. I would look into the mirror and see a whole fucking movie, a horror movie. In the mirror I would see all those four faces. I was hallucinating all the time. Seeing things that weren’t there, hearing shit that wasn’t there. Four days without sleeping and taking all those drugs will do that to you.

I did some weird shit back in those days, too many weird things to describe. But I’ll tell you one. I had a white woman dealer and sometimes—when nobody was at my house—I would run over to her place to pick up some coke. One time I didn’t have no money, so I asked her if I could give it to her later. I had always paid her and I was buying a lot of shit from her, but she told me. “No money, no cocaine, Miles.” I tried to talk her into it, but she wasn’t budging. Then the doorman calls upstairs and tells her her boyfriend is on his way up. So I asked her one more time, but she won’t do it. So I just lay down on her bed and started to take off my clothes. She’s begging me to leave, right? But I’m just laying there with my dick in one hand and my other hand held out for the dope, and I’m grinning, too, ’cause I know she’s gonna give it to me and she does. She cursed me like a motherfucker on my way out, and when the elevator opened and her boyfriend passed me, he kind of looked at me funny, you know, like “Has this nigger been with my old lady?” I never went back by there again.

After a while this shit got boring. When you’re high like that all the time, people start taking advantage of you. I didn’t never think about dying, like I hear some people do who be snorting a lot of coke. None of my old friends were coming around, except Max [Roach] and Dizzy [Gillespie]. Then I started to miss them guys, the old guys, the old days, the music we used to play. One day I put up all these pictures all over the house of Bird, Trane, Dizzy, Max—my old friends.

Around 1978, I think it was George Butler, who used to be at Blue Note Records but was now at Columbia, started calling me and dropping by. There had been changes at Columbia since I had left. Clive Davis was no longer there. The company was now run by Walter Yetnikoff, and Bruce Lundvall was over the so-called jazz arm of the company. There were still some old people who had been there when I retired, like Teo Macero and some others. When George started telling them he would like to see if he could convince me to record again, a lot of them told him it was useless. But George took it upon himself to convince me to come back. It wasn’t easy for him. In the beginning I was so indifferent to what he was talking about that I must have thought I would never do it. But he was so goddamn persistent and so pleasant when he would come by, or call and talk on the telephone. Sometimes we would just sit around watching television and not saying nothing.

Sex and drugs took the place that music had occupied in my life, and I did both of them around the clock.

He wasn’t exactly the kind of guy I had been hanging around all these years. George is conservative and has a Ph.D. in music, but he was black, and he seemed honest and really loved the music I had done in the past. Sometimes we’d talk and then we’d get into when I was gonna start playing again. At first I didn’t want to talk about it, but the more he came, the more I thought about it. And then one day I started messing around on the piano, fingering out a few chords. It felt good!

Around this time, Cicely started coming by more often. We had this real tight spiritual thing. I used to always say to myself that if I ever married someone again after Betty it would be Cicely. I stopped seeing all those other women, and Cicely helped run all those people out of my house. She kind of protected me and started seeing that I ate the right things, and didn’t drink as much. She helped get me off coke. She would feed me health foods, a lot of vegetables and a whole lot of juices. She turned me on to acupuncture to help get my hip back in shape. All of a sudden I started thinking clearer, and that’s when I really started thinking about music again.

Cicely also helped me understand that I had an addictive personality, and that I couldn’t ever again be just a “social” user of drugs. I understood this, but I still took a snort or two now and then. At least I cut it way down with her help. I started drinking rum and Coke instead of cognac, but the Heinekens stayed around for a little longer. Cicely even got me off cigarettes; she said she would stop kissing me if I didn’t stop, so I did.

One of the other important reasons that I came back to music was because of my nephew, Vincent, my sister Dorothy’s son. I had given Vincent a set of drums when he was about seven and he fell in love with them. After high school he went to the Chicago Conservatory of Music; so he was serious about music most of his life. From time to time I would call and he would play something for me over the telephone. I would give him advice, tell him what to do and what not to do. Then when I didn’t play for those four years, Vincent came to New York to stay with me. He would always be asking me to play something for him, show him this, show him that. I wasn’t into doing that at the time, so I would just tell him, “Naw, Vincent, I don’t feel like it.” But he would stay on my case. “Uncle Miles, why don’t you play something?” Sometimes he would get on my nerves with that shit. But he always kept music in front of me when he was there, and I used to look forward to his visits.

It was hell trying to get off all those drugs, but I eventually did because I have a very strong will to do whatever I put my mind to. That’s what helped me to survive. I had had my rest and a whole lot of fun—and misery and pain—but I was ready to go back to music, to see what I had left. I knew it was there, at least I felt it was in me and had never left, but I didn’t really know for sure. During those years people were even saying that I’d been forgotten. But I ain’t never listened to that kind of shit. I knew I could pick up my horn again whenever I wanted to, because my horn is as much a part of me as my eyes and hands. I knew it would take time to get back to where I was when I was really playing. I knew I had lost my embouchure because I hadn’t played in so long. That would take time to build back up to where it was before I retired. But, otherwise, I was ready when I gave George Butler a call in early 1980.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now