Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSoviet Blocks

SPOTLIGHT

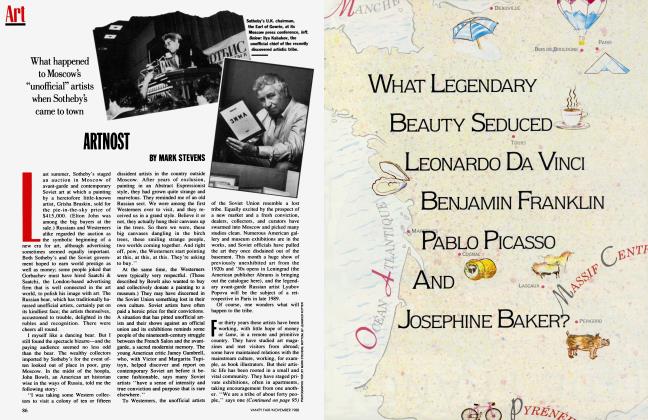

when Kazimir Malevich died in 1935, Stalinist yahoos relegated his revolutionary paintings to the basements of Soviet museums. Now, thanks to glasnost, the bulk of his work can be seen again. A source of great and continuing fascination in the West, Malevich is the subject of a comprehensive retrospective that opens this month at the National Gallery in Washington and then travels to Los Angeles and New York.

More than any other painter, Malevich found a way to reflect the revolutionary rapture of the early years of this century. Best known as the creator of "Suprematism," a rigorous abstract style based upon simple geometric forms (at right, Suprematist Painting, from before 1927), he is a kind of comet, passing across the sky of modernism. His floating geometries and stark squares and crosses reduce art to its essentials—with the implicit promise that, given these building blocks, men will be able to envision a new world.

Countless subsequent artists have made abstract paintings from geometric forms, but few have brought the same elevating passion to art—that sense of having discovered a new dimension of the spirit. Much of the fascination of this show lies in watching Malevich's art first take off from Cubism, then soar with Suprematism, and finally settle down once more—for the Stalinists, with their demand for an art of "socialist realism," did indeed bring Malevich down to earth. His late figurative period is not embarrassing, just ordinary. It is a melancholy landing, emblematic of our century.

MARK STEVENS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now