Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSHARP PENN

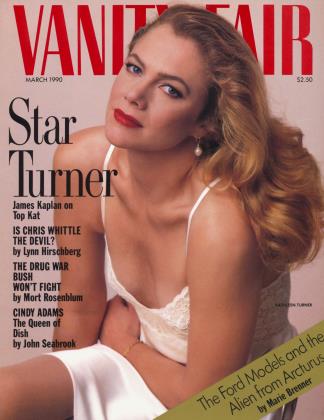

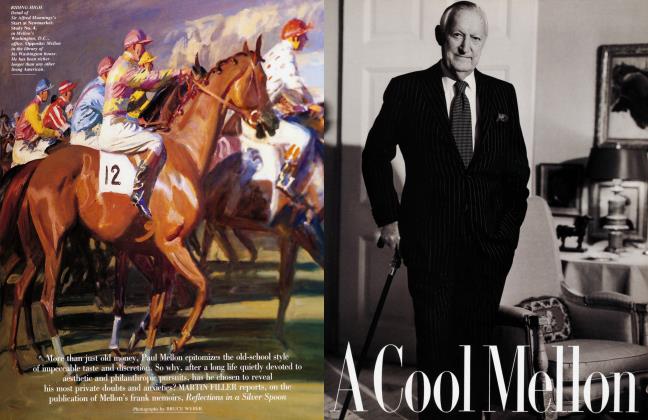

In a rare moment of self-exposure, the reclusive Irving Penn talks with MARTIN FILLER about his legendary career and classic images. As his gift to the nation goes on display in Washington, the master photographer sheds new light on his quest for perfection and his need to control

MARTIN FILLER

Nothing sums up the silent power of Irving Penn— renowned as a photographer but virtually unknown as a personality—better than the way he goes about shooting a picture. For five decades now the world's most sought-after cultural celebrities and fashion models have come to be photographed by this acknowledged master of his art, but what each has encountered is very much the same.

Penn's unfailing sense of control gives a portrait session at his Fifth Avenue studio, in the Flatiron District of New York, the rather clinical feeling of a visit to a doctor's office—an analogy used independently by two former Vogue editors who worked with Penn forty years apart. First, one is ushered into Penn's spare, meticulous, white-and-gray office. His benign, solicitous, but reserved countenance and discreet demeanor are much like those of a respected Park Avenue specialist. Dressed in a brown turtleneck sweater and camel sport coat, he sits behind his desk and chats with his subject in his low, soothing voice. He limits himself to inconsequential topics, establishing a relaxing rapport likely to encourage a favorable outcome to the visit. Meanwhile, in the large adjacent studio—not unlike an operating room—assistants are silently scrambling to set up the necessary instruments for carrying out the carefully studied procedure.

Sometimes a friend or colleague of the subject is invited along to the session to talk with and distract the sitter while Penn goes about his task with all the authority and intensity of a surgeon. He's not a great one for patter while working. While the subject sits at the center of a pool of light, Penn murmurs terse orders to his attentive but anxious staff, who pass film and adjust strobes and spots with clockwork precision.

Most sitters come away from a Penn portrait session with the feeling that it was a far less painful experience than they had feared, though it is far from a laugh riot. And for many it can be a tiring ordeal. For example, the septuagenarian I. M. Pei was placed in an uncomfortable posture atop a high stool with his arms held tightly behind his back. The normally unflappable Pei was then asked to turn and produce his famous impish smile for more than half an hour, a task that left the noted architect's face twitching with tension at the end of the session. Of course, the picture was perfect.

'I can't tell you how comfortable I am with people who can't talk," confesses Penn. In fact, he says he has never enjoyed a fashion session more than when he shot the mannequins for his 1977 book, Inventive Pahs Clothes 1909-1939, with a text by Diana Vreeland. "It was such a pleasure to photograph clothes on dummies," he recalls. "You didn't have to make conversation."

In the worlds of fashion, advertising, magazine publishing, and museums, there is almost unanimous agreement that, as Alexander Liberman—Penn's most important collaborator for almost fifty years and editorial director of the Conde Nast Publications since 1962—says, "a Penn photograph will always be a great photograph." That certainty stems from an invariable consistency, based on Penn's faultless technical command of composition and lighting, his dependence on uniform, systematic studio conditions, his preference for black-and-white despite a superb talent for handling color, and his ability to poignantly capture an evanescent moment in time.

Penn's seemingly fail-safe knowledge of what he can and cannot do is another secret behind his superlative output, as are his capacity for hard work and his dogged perfectionism. The latter is something that all his colleagues comment on. Liberman puts it this way: "One of the interesting things about Penn is what he has in common with several other American artists: the inability to do otherwise. It is the obsessive drive to achieve the desired vision, in the same way I've seen Barney Newman insist that workmen cut a piece of steel a hundred times until it satisfied him. Penn sometimes will take a hundred pictures, practically identical, until that very slight thing that he's searching for is achieved."

But rather than depicting his career as a quest for uncompromising quality, Penn himself puts it in characteristically self-deprecating terms. "I'm a surprisingly limited photographer," he says, "and I've learned not to go beyond my capacity. I've tried a few times to depart from what I know I can do, and I've failed. I've tried to work outside the studio, but it introduces too many variables that I can't control. I'm really quite narrow, you know."

Former Vogue fashion editor Babs Simpson remembers, "Irving would put those poor girls into some impossible contortion and then ask them to hold the pose for twenty-five minutes, and then he'd complain that they didn't look spontaneous and they'd burst into tears." But even with inanimate objects there was always the same relentless drive toward the ideal. "There's the famous story of Irving photographing the lemon," Simpson recounts. "First, you had to buy five hundred lemons for him to pick the perfect one. Then he had to take five hundred shots of that lemon until he got one that was perfect." Penn is not unaware of his behavior. "I know I'm obsessive," he admits, "but I think that's what propels me in my work. In fact, I never tell people what to do. I simply say, 'What would happen if you did this?' "

As he wrote in a revealing (and prophetic) self-portrait published in Alexey Brodovitch's short-lived magazine, Portfolio, in 1950, "I feel comfortable in looking at a baseball diamond. It is for me typical of the formalized, unchanging stages on which a variety of chance human and space relationships can occur. I have at times found it satisfying to work in a studio with a fixed set and pre-determined lighting, the human relationships being the only day-to-day variant."

(Continued on page 222)

"I can't tell you how comfortable I am with people Who car't talk," confesses Penn.

(Continued from page 186)

The highly organized, supremely rational Penn often found the signature dictates of the oracular Vogue editor in chief Diana Vreeland to be little more than gibberish during the decade he worked for her after she took over in 1962. "One day Mrs. Vreeland called me in and told me she wanted me to fly to Spain to photograph the queen of the Gypsies, who bathed in milk and had the most marvelous skin in the world. I found out that the Gypsies camped on land owned by the husband of Aline, Countess of Romanones, who sounded a bit puzzled but said I was welcome to come over. Well, not only wasn't there a queen of the Gypsies, but they never bathed, let alone in milk. The whole thing was a fabrication. I took some pictures that I thought were rather interesting anyway, if not what had been asked for. And when I got back to New York and told Mrs. Vreeland, she looked at me blankly and said, 'What queen of the Gypsies?' as if she'd never heard any of it before in her life."

Penn early on found he needed to explore his own interests in photography as a ballast against the capricious whims of the fashion world. In 1949 and 1950, at the height of his most brilliant and rarefied fashion work for Vogue, he moonlighted on a series of nude studies of farless-than-perfect female torsos. Liberman encouraged Penn to keep up with this "serious" photography, recalling, "I always said to him, 'This constant working on the magazine can be a terrible drain. One has to regain one's soul in a pure pursuit.' " For Penn it restored a crucial sense of perspective: "After a full day of trying to capture the most beautiful women in the world, I felt it was necessary to work on something quite the opposite to give myself a more balanced diet. I was very much influenced by Bill Brandt's work, and the implication that not everything is going to be perfect forever."

Penn did, however, choose for his wife the pluperfect blonde Lisa Fonssagrives, perhaps the greatest beauty of all among a generation of fashion models that he immortalized in a well-known 1947 photograph, the shooting of which brought them together for the first time. "In those days there were Vogue models and Bazaar models, just as there were Vogue photographers and Bazaar photographers, and the two didn't mix. But I was assigned to shoot the twelve most photographed fashion models. When Lisa came in, I saw her and my heart beat fast and there was never any doubt that this was it." They were married three years later, and in 1952 their only child, Tom Penn, now a New York furniture and graphic designer, was bom. (Irving Penn is often thought to have been the real-life inspiration for the fashion-photographer-shoots-and-falls-inlove-with-and-marries-his-model plot of Stanley Donen's 1957 film, Funny Face, but in fact the role is based on the rather racier personality of Penn's younger rival Richard Avedon.)

Penn's memories of being one of the world's most successful fashion photographers are not entirely negative, however much he might like to expunge that primary association from the history books. "I remember the first time I went to Paris to cover the collections. Alex called me and told me that I'd need to go out and buy myself a dinner jacket. Can you believe it? In those days the showings were at night, black-tie, no mob of paparazzi, no loud music. Just little gold chairs, huge arrangements of flowers, champagne, very civilized. Then the girls came out, and they were so snotty to the audience. It was wonderful." But, as Liberman adds, "Penn is greater than his fashion reputation. His pictures are not amusing. They're not about pleasure, they're not about entertainment. They're about something lasting, and are surrounded with a stillness. Even his portraits have the stillness of still lives."

The powerful black-and-white portraits that Penn began producing during the late forties for the feature pages of Vogue (which then incorporated Vanity Fair) caused just as much comment as his fashion spreads. His sure grasp of the genre was there from the outset. While on a yearlong volunteer stint as a photographer with the American Field Service during the last phase of World War II in Europe, Penn spotted one of his major artistic heroes, the painter Giorgio de Chirico, walking near the Spanish Steps in Rome. Penn stopped the aged master, expressed his profound admiration for his art and what he had learned from it, and asked if he could photograph him.

It was the first in a long line of luminaries that includes some of the most distinguished names in twentieth-century arts and letters—George Balanchine, Saul Bellow, Willem de Kooning, Marlene Dietrich, Marcel Duchamp, T. S. Eliot, Duke Ellington, Max Ernst, Suzanne Farrell, Jasper Johns, Barnett Newman, Isamu Noguchi, Georgia O'Keeffe, Isaac Bashevis Singer, David Smith, Igor Stravinsky, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, among others.

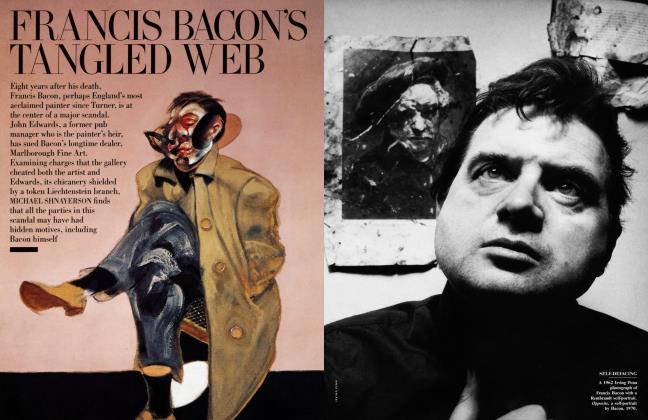

Sixty of Penn's best portraits, including those mentioned above—chosen, printed, and donated by the artist himself—are the subject of the exhibition opening this month at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Since the mandate of the museum is limited to images of U.S. citizens or those closely associated with this country in some way, several of Penn's most memorable portraits are missing from the selection. But they are present in a second gift of another sixty prints to the National Museum of American Art, also in the capital, and are on view simultaneously with the Americanportraits show, which together Penn proudly calls "the cream of my work." Among that second group are Penn's photographs of Francis Bacon, Jean Cocteau, Salvador Dali, Alberto Giacometti, Le Corbusier, Joan Miro and his daughter, Dolores, Henry Moore, and John Osborne.

If Penn does not exactly require his sitters to have a certain eminence, he does prefer a certain degree of experience. Robert Mapplethorpe once spoke ecstatically to an interviewer about photographing Richard Gere, and indeed his portrait of the handsome actor, suffused in a pearly glow, is one of his most tender. Duane Michals, who shot Gere for Vogue, and Herb Ritts, who over the years has taken innumerable pictures of the movie star, have also confided to friends their enthusiasm for their subject. But not Penn.

"When they called from Vogue and asked me to photograph Richard Gere, they told me they were sending me 'a hunk.' I told them I didn't think he was for me—when I photograph a man, I've got to have something to hang on to, some character, not just another pretty face, and I was afraid he didn't have it. Now, with I. M. Pei you know that there are five thousand years of Chinese history behind that face. But I've heard that Gere has become quite interested in Buddhism and the Dalai Lama lately, so maybe he's ready for me now."

Penn's memories of what happened at a sitting—though he usually dislikes talking anecdotally about his art—remain as sharp as the images he captured. Among his most incisive portraits is his 1950 photograph of Cecil Beaton, which in Penn's platinum-palladium print has the silvery sheen of a Gainsborough. Atypical of Penn in its outright romanticism—Beaton is swathed in a billowing opera cape— it is a tour de force in which Penn almost parodies his sitter's own photographic style by out-Beatoning Beaton. Penn still remembers his astonishment at his subject's last-minute preparations. "Just before I was about to begin, Beaton took out a pen and drew hair in on his forehead to make himself look less bald. It was something, if you were going to do it at all, that you'd do in a bathroom behind a closed door, but he was absolutely without shame. He was a completely theatrical personality, and doing that in front of me was his way of saying that we were conspirators, fakers together in this art of fakery. ' '

The artist Saul Steinberg, a notoriously prickly character, became more and more visibly upset while Penn worked on his portrait in 1966. "Finally I asked him what was wrong and he said, 'Only you're getting to do what you want to, and I want to do something that I want.' " Penn assented, and Steinberg improvised a cardboard mask with tiny eye holes and a cutout slit for his nose, a whimsical but off-putting image that is among the most intriguing of those in the National Portrait Gallery donation.

Not all of Penn's memorable sitters have been cultural Olympians, and a retrospective of one hundred of his most unconventional portraits, "Other Ways of Being," will be shown this month at New York's Pace/MacGill Gallery. These include Penn's documentation of America's emergent counterculture during the late sixties, with appearances by Janis Joplin ("She couldn't have been more ladylike or sympathetic," Penn now says) and the San Francisco chapter of the Hell's Angels ("We had a grunting relationship"). For the most part, however, this exhibition is composed of Penn's ethnographic work, an area that has fascinated him ever since his landmark shoot for Vogue in Peru in 1948 but that he wasn't able to fully indulge in until his fashion photography was less in demand.

"I don't want to photograph what I can A see," Irving Penn says. "I want to photograph what I can discover." His lifetime of discovery began in 1917 in Plainfield, New Jersey, where he was bom to Harry and Sonia Greenberg Penn. He was raised in Philadelphia, where in 1922 his brother, Arthur Penn, the film director, was bom. Their father was a watchmaker, their mother a nurse, and it is tempting to ascribe the elder son's fascination with order and precision—and even the passage of time, aging, and death—to their occupations. Irving Penn has rarely spoken about his early youth, but in the words of one close friend who asked not to be identified, "there were dark hints about unhappiness in the home, and it was clear that it was not a cheery childhood."

There was also a competitiveness between the brothers that generally favored the elder over the younger until Arthur burst into media stardom with his 1967 smash, Bonnie and Clyde. "It was a very difficult time for Irving," a close colleague during those years now remembers. "He had been going through somewhat of a slump in his own work and then suddenly there was Arthur in every magazine and newspaper. Arthur had always been Irving's younger brother, and now it was the other way around. It was very hard for Irving to take. Not long after that he started to do all those depressing photographs of garbage, and I think that Arthur's success had something to do with it."

At the age of seventeen, Irving Penn entered the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art, where he took courses with the legendary graphic designer Alexey Brodovitch, art director of Harper's Bazaar, who gave the young student a summer job at the magazine after his junior and senior years. Penn graduated in 1938 and moved to New York, where he worked as a freelance commercial artist for Brodovitch and others. His early mentor got Penn the job of art director for Saks Fifth Avenue's advertising, but after only a year he quit to pursue his increasingly serious artistic interests.

Penn had started photographing in the late thirties, and what he has said about such self-taught photographic geniuses of the nineteenth century as Matthew Brady and Nadar could apply to his own beginner's work as well: "They reached a maturity almost as they began." One of his earliest and most durable images, Optician's Window, New York, circa 1939, though obviously influenced by the then fashionable Surrealists, already displays the confidence and forthrightness that are hallmarks of his mature work. A 1941 series of pictures of poor blacks in the American South owes a strong debt to such Depression-era greats as Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans, but once again the distinctive Penn attributes of clarity, structure, and an eye for the unexpected found object were all already firmly in place.

Just before America's entry into World War II, Penn went to Mexico for a year to paint. After his return to New York in 1943 he was hired as an associate art editor at Vogue by Alexander Liberman, with whom he was to forge one of the most fruitful artistic collaborations in the history of publishing. Their association has resulted in what must be seen as a rare, perhaps unique, act of sustained artistic patronage by a magazine company, one in which the traditional boundaries between high art and commercial art were repeatedly blurred, though rarely compromising the former or reducing the effectiveness of the latter.

Penn became Liberman's alter ego, executing photographs exactingly following the art director's pencil sketches. "Penn is a graphic photographer," Liberman explains. "He draws, and out of his drawings—my drawings, sometimes—comes a vision that is, in a way, two-dimensional. It's practically a typographical vision. An enlarged letter has a great resemblance to a Penn portrait. But on the page it prints and in the magazine it stands out. He needs the printed page."

Using a large-format, eight-by-ten-inch camera that obtained the maximum definition for engraving of an almost hallucinatory clarity, Penn devised a pristine, hardedged format that was quintessentially modernist. With Liberman as his guide, Penn did away with the chichi conventions of the fashion photography of the twenties and thirties. "When we were beginning together," Liberman remembers, "it was an epoch when 'visions of loveliness' was the demand. It was Park Avenue taste, everything pink and lovely and pretty. Horst was doing lovely feathers. Beaton was doing I don't know what in his studio. And Penn loved decay, loved ashes, gave a little sort of lemon twist to everything he did. Penn was a social critic in many ways, so there was an element of revolution, or critique or destruction, a certain undertone of violence, in his work. I admired it very much because it was important to shake up the illusions."

Involved poses and fussy backdrops gave way to iconic images shot against gleaming white no-seam paper or interestingly textured industrial felt, photography bold in outline, striking in its severity, and quite unlike anything either in other magazines or in advertising. Readers had no doubt where they were inside the pages of Vogue. "It was all about purity," says Penn now with more than a touch of wistfulness in his voice. "Those fashion pages in Vogue were an island of belief that the reader could have, that this part of the magazine was being done by someone who was talking straight. Of course, there was also something very unreal about it, too— trying to attain unattainable luxury."

It was the ideal moment in history for Penn's new approach to depicting fashion, the direct equivalent of the classic work of such older, second-generation American modernist contemporaries as Gordon Bunshaft in architecture and Franz Kline in painting. The postwar revival of the French couture houses, culminating in the epochal New-Look, launched by Christian Dior in 1947, required a novel presentation in keeping with the clothes themselves, and Penn provided it. These were not the sinuous, bias-cut dresses of the immediate pre-war period, but rather the highly structured, boned-and-padded creations for a very different female silhouette. "Those dresses could almost stand up on their own," Liberman remarked years later, and in their highly graphic way Penn's fashion photographs of the forties and fifties were as perfect an expression of their time as Baron Adolf de Meyer's dewy-eyed fantasies on the exoticism of Poiret and Fortuny had been three decades earlier. In the opinion of Maria Morris Hambourg, a curator of photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, "after the end of this century, when we look back at what was done in fashion, Penn will be at the top of the heap."

Nonetheless, as Babs Simpson maintains, "Irving never really did like fashion, and with Diana's way of stagedirecting—no, movie-directing—every shot, calling photographers in to rehearse every pose, it's no surprise they couldn't work together." Increasingly, at Vogue, Penn was passed over for the more improvisational Avedon, and it remained for Liberman to tell his protege in the late sixties that Avedon would be doing more of Vogue's fashion pages in the future. "I wandered the streets at night, unable to sleep and wondering what to do with my life," Penn now recalls. But there was also a great sense of relief that his ordeal with Vreeland was over. "I stopped being her fashion cow, milked for every fantasy she had."

He then began what he describes as the most satisfying part of his professional life, his photographic expeditions to Third World outposts before, as he believes, tribal cultures became irretrievably corrupted by "civilization" (though in fact almost all of them had been compromised long before then). There was a pronounced nineteenth-century feeling to Penn's descriptive, head-on documentation of Enga, Okapa, and Tambul warriors in New Guinea, ritually scarified beauties in Dahomey, turbaned village elders in Morocco, and the Chhetri women of Tibet. But Penn's reluctant exposure to the world of high fashion also gave him a sophisticated understanding of the psychology of human adornment, and no Victorian photographer-explorer was as sympathetic or knowledgeable when it came to presenting fantasy dressing to a Western audience.

During the late sixties and early seventies Penn also turned more and more to deliberately unbeautiful subject matter, though he had delved into that contrary vein before. He began to photograph refuse—albeit very handsome refuse— picked up off the street. These richly textured black-and-white close-ups of cigarette butts, paper cups, take-out containers, wrappers, and rags were printed in large-scale images to emphasize their impact. As Liberman observes, "He gave nobility to garbage. The cigarettes remind me of Egyptian mummies." But the photographs met with the art world's indifference or hostility, which clearly still rankles Penn. He refers to those subjects, similar to those of the contemporary Arte Povera movement in Italian art, as having been "put down by critics."

Various explanations have been offered. According to Liberman, "It was the stigma of Vogue." Maria Morris Hambourg believes that the time and place of those shows worked against Penn. "Coming on the heels of Rauschenberg and Warhol, and the greater power and violence of their appropriations, the Penns seemed so pretty, so elegant. It was a real contradiction that made it difficult and ambiguous, but I find it among his best work. Also, if he had shown them at Castelli downtown, they would have been received differently. But at the time he showed them at Marlborough, anyone with any sense was looking elsewhere for innovative art." His ultimate revenge is to have included four prints of those street findings in his gift to the National Museum of American Art. Significantly, only three fashion photographs from his glory years at Vogue have been deemed by Penn worthy of posterity in this group—all of them, not surprisingly, depicting Mrs. Penn.

As the forty years of their marriage have progressed, the reclusive Penns have seen less and less of life in New York, to which he commutes every working day from their unpretentious house in Huntington, Long Island. There she gardens, and during the late sixties she provided him with the raw material for yet another of his decay themes: cut flowers well past their prime but still beautiful as their colors begin to fade. ''He'd cringe if you said he has a philosophical turn of mind," observes Hambourg, ''but he has a sense of the ephemeral quality of nature. That's fundamental to him. He's more concerned with death than with manifestations of living. For him, life is an inexorable movement toward the other. ' '

Some amateur psychologists took those flower Ektachromes to be Penn's meditation on his wife's aging, though even in her late sixties she remains thoroughly arresting. At the premiere of a documentary film of the art of Alexander Liberman at New York's Guggenheim Museum in 1985, the Penns made one of their now rare nighttime appearances at a Manhattan social gathering, and she still turned heads. Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn has eschewed plastic surgery, but her face, now softened into a parchment of tiny lines, retains the ethereal glow that makes it easy to understand the quality she gave off at her physical peak. Even today she seems as though she is lit from within, her impressively high cheekbones continuing to give her face an architectural strength.

The only fashion that much interests Penn these days is that of the Japanese designer Issey Miyake, whose clothes he has been shooting over the past decade and which were the subject of his 1988 book, Issey Miyake. "We have an incredible relationship. He sends me his clothes and says, 'I don't even want to be on the same continent while you work,' which is what I do. He says that what we have is called in Japanese 'a-un'—which means 'silent communication.' " Whatever one calls it, it is clear that Miyake's startling, idiosyncratic designs have excited Penn's creative imagination in a way that no clothes have in decades, and the liberties the photographer takes with them are metaphors for the release he feels when not having to abide by requirements incumbent on a magazine professional.

For the sake of an arresting silhouette, Penn will take a voluminous Miyake jacket and inflate it with an air pump, or coax the model into such an abstract form that the human figure is virtually unrecognizable. As effective as these images are in conveying the audacity and surprise of the new Japanese fashion design, one also has the sense that these photographs are at once exorcisms and penances for all those years Penn shot fashion but felt he ought to be doing something else.

Despite the disappointing response his "serious" work of the seventies and eighties received, Penn's fame has continued to mount steadily, culminating in his retrospective at New York's Museum of Modem Art in 1984. (There is only one Penn photograph dating from after the MOMA show included in his double-barreled gift to the nation—a 1986 silver print of a zebra skull taken on a trip to Prague.)

He continues to work for Vogue, still shooting fashion and creating surreal illustrations for the magazine's beauty features. He also works on a parallel track for many commercial clients, though his advertising photographs (for Jell-O Pudding and Plymouth in the fifties, Johnson & Johnson in the sixties, and Clinique in the seventies and eighties) are of a piece with his more consciously artistic efforts. Liberman points out why: "His photographs have a very extraordinary imprinting quality. They last in the memory, and it's not surprising that he's also so successful in advertising. It's the same imprinting—refining things to that one essential shape or vision."

I stopped being Vreelands fashion cow, milked for every fantasy she had," says Penn.

Lately, Penn has become increasingly concerned with shoring up his historical legacy. Long preoccupied with the quality of his prints ("He's unparalleled as a printmaker," says Hambourg), Penn produces them all under his own supervision at darkrooms in New York and on Long Island, and has also been methodically creating new prints of some of his greatest images. He emphatically does not want anyone else to make prints of Penn photographs after his death. The late Ansel Adams, for example, ceased printing during his lifetime and thereby spurred skyrocketing prices for his existing work. According to photography dealer Robert Mann of Fotomann, Inc., in New York, Penn's practice is to print a limited edition of a photograph, sell half of it immediately to establish its value, and then retain the other half for his own gradual distribution, with each successive print in a series bringing a correspondingly higher price. But Penn's main motivation is an elemental need to be in control, the thread that runs through half a century of topically diverse but stylistically unified work.

Penn feels most self-assured when his subjects are most controllable, a condition that he has found innumerable ways of maintaining. Back in the late forties, he placed his portrait subjects in a narrow comer of his studio, often hunched between the tight angles of the oblique space. "They couldn't run away, and they belonged to me as subjects for that moment of time. They felt good about it, too," he says. "Their rears were protected and they could project their attitudes outward in one direction."

It was much the same with his tribal subjects of the seventies. "It was difficult to direct them, because I couldn't tell them to move. When I would reach out to put them in a certain position, they thought it was an embrace and put their arms around me. We lost a lot of time doing that. But then I realized that there is one gesture that is the same in every language—pointing one finger up to mean 'Don't move.' That was a very comfortable discovery for me."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now