Sign In to Your Account

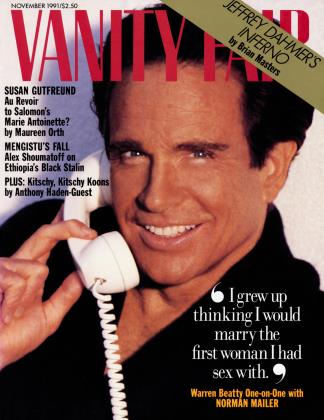

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLE BERNIER CRI

Why Rosamond Bernier, whose new book is about her friends Matisse, Picasso, and Miró, is as much a star of high society as high art

Books

ADAM BEGLEY

I here's a small country house in Connecticut—plain, beige, utterly unsuited to the cosmopolitan grace of its inhabitants or the muted New England beauty of its setting—and a pied-a-terre in Manhattan, a cramped four-room Rat that doubles as Rosamond Bernier's office, where she concocts the art lectures that have made her a prized exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum. A studio apartment five floors below, bought when her husband, art critic John Russell, retired after sixteen years at The New York Times, is his cluttered lair, stacked with outsize art books and bulging dossiers that seem to breed reams of his lucid, unhurried prose. Sprinkled liberally around their Manhattan digs, as in their country house, are the mementos of five decades' friendship with artists, writers, and composers—paintings, objects, and books that connoisseurs with good taste, little money, and many talented friends manage to gather.

Neither place holds them for long. Rosamond's exquisitely cultivated voice, with an accent artfully poised high above the mid-Atlantic, is heard in museums and theaters and concert halls across the country and around the world (videotape and television have extended her reach); John Russell follows the trail of exhibitions—he looks, he writes, but, hampered by a stutter, he rarely speaks in public. This month Knopf will publish Rosamond's first book, Matisse, Picasso, Miro: As I Knew Them, an elaboration of one of her more popular lecture series. Together, Russell and Bernier are a latter-day version of Moses and Aaron: their inspiration may not be divine, but they do come down from the mountain bearing the word on high culture. He has the authority, though perhaps not the popular touch; she sways the masses.

They live, in fact, where high art and high society intersect—not at the benefit ball or the upscale gallery opening but in the old-money houses of the very rich where the great private collections are hung. If to the public they are educators of a sort, to New York society matrons they are soigne representatives of the arts, lustrous ornaments to liven the tired formalities of a seated dinner. When it comes to singing for their supper, they perform a Mozartean duet.

Before they joined forces seventeen years ago, they had each been married twice, and each enjoyed a certain eminence, he as an author and as art critic for The Sunday Times in London, she, in Paris, as the co-founder and co-editor (with her second husband, Georges Bernier) of L'Oeil, a magazine that Alexander Liberman, editorial director of the Conde Nast Publications, calls "the most remarkable art journal of its time." Though they are both over seventy, they are as busy—and as ambitious—as they were when they first met in the 1950s. Russell is under contract to produce an article per week for The New York Times; at the same time, he's writing a book on London similar to his copiously illustrated Paris, which has sold nearly 100,000 copies since it appeared in 1983. Rosamond is polishing lectures for her twenty-first season at the Metropolitan Museum; she will also speak in San Francisco, Chicago, Baltimore, and Houston. She spent this past summer preparing the video release of last year's series at the Met and working on articles for HG, where she has been an editor-at-large for the last eight years.

"I don't think her manner is put on ," says Jerome Robbins, "but I'd like to see her off-balance once, or caught in the rain."

Strapped side by side on a banquette aboard a hired Falcon 20 jet, Rosamond Bernier and John Russell exude a quality indispensable to their "gypsy life," as Rosamond calls it: they are everywhere at home. Anne Cox Chambers, perhaps the richest woman in America and the doyenne of Atlanta society, is ferrying them, and herself, from New York to Atlanta, where Rosamond is to lecture at a gala benefit celebrating the silver anniversary of the Forward Arts Foundation. Rosamond trades news with Mrs. Chambers; Russell reads The Times Literary Supplement; Emily, one of the three dogs in Mrs. Chambers's entourage, scratches furiously at the leather of the seat she has chosen as her own. Takeoff silences the conversation, and by the time the plane has leveled off, Rosamond and Russell are hard at work, each with a sheaf of papers and a pencil. Rosamond is cutting passages from a lecture on Catherine the Great, part of her series on royal collectors; the script is too long for video. Making tiny marks in the margin, she moves rapidly through the text. Once she's done, she passes Russell the manuscript and he goes through it slowly, jotting notes, while she peers over his shoulder. His task completed, he goes promptly to sleep, his striped green bow tie unknotted, the collar of his striped yellow shirt unbuttoned. With his bluff English face, pink and handsome, he looks like good King Wenceslas, though awake he's hardly the hail-fellow-well-met type. He has a temper that flares unexpectedly, and he favors pointed asides and wellhoned irony. Surveying the scene on the windswept airport runway—Mrs. Chambers's two cars, three dogs, four servants, and piles of baggage—he sums it up with a nod: "Worthy of Fellini."

Rosamond is not the sort to nap in the company of friends. Slim and spry, she wears a purple Saint Laurent suit; as always, she gives the impression of having dressed with the pleasure of others in mind. When she chats with Mrs. Chambers, a lively expression of intelligent, concentrated attention lends beauty to an otherwise pretty, oval face; she resembles a brilliant geisha, skilled in a thousand secret ways to make life agreeable. Though dispensed democratically—even to the casual acquaintance—her solicitude explains in part the devotion of a vast circle of ardently protective friends. If she cultivates this talent, then all traces of her labor have been effaced to guarantee the semblance of effortless poise. "I don't think her manner is put on," says Jerome Robbins, a friend for some forty years, "but I'd like to see her off-balance once, or caught in the rain. I'd like to hear her say 'Oh, shit'— though I'm sure she does and it comes out all right."

When Rosamond sweeps onstage in Atlanta, sheathed in a deep-pink Bill Blass gown with black lace sleeves and a black lace top speckled with paillettes, generous clusters of costume jewelry glinting in the spotlight, and delivers a sprightly peroration, there's no sign of strain—no sign that in this case at least her flawless polish is achieved only with liberal applications of elbow grease. The clothes set the tone: this is a performance, not a lecture, a diverting mix of substance and froth. By the time she has taken her place beside the lectern and the first slides have lit up the screen with broad splashes of color, her audience, some two hundred well-heeled Atlantans decked out for the black-tie benefit, has all but forgotten about the dinner dance to follow. This is her kind of crowd: educated but without expertise, worldly enough to appreciate the zest of her anecdotes but not hungry for cutting-edge scholarship or provocative theory. She tells the story of her friendships with Matisse and Picasso, adds a number of lively remarks on their late work, and this takes her two-thirds of the way. She ends up on the Italian Riviera, gamboling in the waves with Henry Moore.

In her repertoire she has more than thirty lectures, on everything from gardens and art to jewelry and art. But no matter how familiar she is with her subject, her preparation is uniformly meticulous, with an attention to detail that extends well beyond the business of updating and fine-tuning her text.

John Russell attends his wife's lectures whenever he can. He is a sweet stage-door Johnny, an anxious impresario, a brisk wardrobe manager. He wields the tape to fix the cordless mike inside her dress ("If I put it in my underwear," she explained to the Atlanta projectionist, "it risks falling out"), and paces beside her for the tense half-hour before she goes on—she will see no one else. After more than two decades of public speaking she's still afflicted with harrowing stage fright, jitters that vanish the moment she steps in front of the audience. Isolated by the spotlight, elevated by the stage, marked by her costume as a performer, she reveals her great secret, her most valuable geisha gift: an inimitable knack for projecting intimacy.

Rosamond's book, Matisse, Picasso, Mird: As I Knew Them, though sprightly, readable, and crammed with excellent reproductions, demonstrates that the appeal of Rosamond's lectures is Rosamond in the flesh. Onstage, she breathes life into anecdotes in a way that she can't on the printed page. Her bons mots about great paintings, enchanting in the guise of spontaneous tribute, lose a touch of their wit when presented as art history.

Indeed, if not for her singular talent as a performer, it's a safe bet that her booking agent wouldn't get many calls, for at $10,000 per appearance, Rosamond Bernier is easily the world's most expensive art lecturer.

Calvin Tomkins momentarily arrested the flow of his glowing New Yorker profile of Rosamond Bernier several years ago to introduce and then dismiss "a surly fellow"—a skeptical doppelganger—who asks pertinent but "tasteless" questions, among them the following: "Did Mme. Bernier have any friends who were not famous?" The question can have been prompted only by Rosamond's penchant for peppering conversations with exalted names. One hears of summer weekends in Dark Harbor with Brooke Astor, birthday visits to the Agnellis in Italy, and trips to Paris to stay with the Aga Khan. Let the skeptic ask directly: Does Rosamond seek these people out, or are they drawn to her? Is she diligent or just lucky?

She charmed a brilliant crowd of friends, among them the leading lights of the School of Paris-Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Miro, and Leger.

Rosamond's good friend Philip Johnson has known her for some thirty years. As he said to her over lunch at the Four Seasons in the late sixties, after the sudden collapse of her second marriage and the consequent end of her association with L'Oeil, "Wherever you go it's going to work. You just weren't bom for anything but success." Indeed, with the notable exception of her calamitous divorce from Georges Bernier, she has skimmed from triumph to triumph. While others, however talented, toil along, one rung at a time, Rosamond seems equipped with a private escalator designed to deliver her, unruffled, ever gracious, to the very top.

In the art world, as in the dizzying circles of New York society, there is no shortage of the bitter envy bred by the success of others. Rosamond and her husband are easy marks: though the ready cash of the newly rich boor seems to leave them cold, they are clearly drawn to sophisticated luxury and the easy refinement of cultured inheritors. (Says one sharp-tongued acquaintance, "Rosamond has a homing device that leads her to the richest person in the room.") The attraction, however, is mutual—and why not? Envy abounds, but there has never been a surplus of elegant, distinguished, and brilliantly connected couples who are also eager—and more than competent—to please.

Rosamond Margaret Rosenbaum— known as Peggy until John Russell expressed his preference for her given name—grew up outside of Philadelphia, daughter of a prominent lawyer. Her schooling at an English girls' school, chosen by her English mother, was cut short by a bout with tuberculosis; her college days at Sarah Lawrence came to a similarly abrupt end in 1937 when she married Lewis A. Riley and moved to Acapulco. Although the marriage lasted only a few years, it cannot be counted a failure. While in Mexico, Rosamond met Jose Orozco and Diego Rivera, who—along with Max Ernst, whom she befriended at Sarah Lawrence—were her first painter friends. She also perfected her Spanish, which turned out to be her trump card when she met Picasso in Paris in 1946, a year after

her breakup with Riley. Newly single, Rosamond headed to New York and got a job at Vogue. Within twelve months the magazine sent her to France as its first European features editor. Ten years later she was the toast of Paris.

She met and married Georges Bernier, a former journalist, in 1948, and together they founded L'Oeil in 1955 with a small subsidy from a friend. The magazine, a beautifully produced, trendsetting arts journal, was an instant success, attracting an avid and influential audience and glowing notices in the French press and across the Atlantic as well. Life and Time both pitched in at once, and soon after came the flattering magazine spreads about the pretty expatriate, her French husband, and their "ambitious" art review. Janet Flanner, writing in The New Yorker, declared that L'Oeil "offers the luxury of intelligence, serious information, and magnificent color reproductions"—and all this, as Harper's Bazaar pointed out, for the price of a sandwich au jambon. Rosamond herself charmed a brilliant crowd of friends, among them the leading lights of the School of Paris—Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Miro, and Leger— most of whom she had met through her work for Vogue.

L'Oeil was very much a collaborative effort. Though neither of the Berniers had any artistic talent or any training in art history, they were both intellectually curious, and they plunged fearlessly into what was then the world's most vibrant art scene. Georges brought to the magazine a capacious and combative intelligence—art dealer Eugene V. Thaw remembers him as a "brilliant but difficult and complicated man." Rosamond added driving energy (Thaw also noted that "Georges could be lazy and facile"), as well as a talent for layout, a sharp eye for good stories (she wrote so many articles in the early issues that she took to signing them with different names), and, of course, access to the best artists.

Picasso unearthed for L'Oeil a cache of early paintings he'd left in Spain with his younger sister; Miro, usually shy of journalists, provided the magazine with an artist's guide to Barcelona; Leger, whose work adorned the cover of the first issue, gave a celebration dinner at his house in Gif-sur-Yvette. Rosamond also attracted writers: Cyril Connolly, Alfred Barr, John Richardson—and John Russell.

L'Oeil was breaking even after just two years. The enterprising Berniers branched out into book publishing (Mary McCarthy wrote Venice Observed for them), opened a gallery, established themselves as dealers, and took an apartment in New York so as to keep in touch with the American scene. In short, they prospered. But just before Christmas 1968, Rosamond flew to New York to look for a larger apartment. Bernier arrived two weeks later bearing gifts— Guerlain perfume and a suit from Gres. He announced that he was taking her to lunch, and over champagne at a neighborhood restaurant explained that he was leaving her. She was to stay in New York, and he would provide her with $10,000 a year.

The shock of betrayal, followed by bitter, protracted divorce proceedings, left Rosamond in a state of near collapse—"It was the low point of my life," she says, and declines to discuss the particulars of Bernier's behavior. "The circumstances were so appalling," she adds, "and digging all that up after so many years—I don't think it would be very elegant." Rumor has nonetheless spread the news of certain appalling circumstances, among them Georges's passionate interest in a well-connected Frenchwoman and an illegitimate child he fathered with another Frenchwoman (whom he subsequently married).

Olivier Bernier, who was seven when Rosamond married his father, offers a blunt condemnation of his progenitor: "He was really most odious." Olivier's stepmother taught him English, prompted his interest in the arts, helped him get admitted to Harvard. He has hardly spoken to his father since the divorce, and gushes praise for Rosamond, who has also fostered his career as a writer and art historian, and introduced him to the lecture circuit she had already conquered.

Her own introduction to the world of art lectures she owes to the ingenuity of a friend, Michael R. T. Mahoney, who became chairman of the fine-arts department at Trinity College in Hartford in 1968. Having heard Rosamond launch into impromptu explications of Surrealism, or of Cubist paintings in the Orangerie, he asked her to give a series of lectures to his students in the spring of 1970. "It was then that I realized," says Mahoney, "how electric this live wire could be." Success at Trinity led to an invitation from another friend, Dominique de Menil, then director of the Institute for the Arts at Rice University. Rosamond's lectures at Rice, open to the public, spilled over into an adjoining hall, where closed-circuit TV and duplicate slides offered a pale simulation of Rosamond's new magic. And then on to the Metropolitan Museum, where she filled the seven-hundred-seat Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium after only her fourth lecture. For two decades, her annual series at the Met has always sold out some six months in advance.

When I first met Rosamond I was totally captivated," Russell says. "It was, however, totally hopeless."

So she was back on her feet—and happily, though not deeply, involved with a much younger man—when John Russell reappeared on the scene.

On a hot and humid summer day in Connecticut, Rosamond serves lunch in the bedroom; the drone of the only air conditioner in the house explains the peculiar venue. Once seated on either side of a lone interviewer, Rosamond and her husband begin an elegant and complex verbal tennis match. Neither likes to boast, but each would like the other to shine. Russell, not as adept as his wife at media manipulation, quickly falls behind, and finally resorts to a desperate gambit. Breaking off a halfhearted description of his early career, he asks, "Why not just leave me out of it entirely?" She volleys, her stroke a textbook illustration of Rosamond Bernier in top form: "I wouldn't exist without you," she exclaims. "It would be like— you know, there was a wonderful act that Lenny Bernstein and his sister Shirley did of the Andrews Sisters with only two of the three sisters. The three of us traveled in Spain for a month in 1950, and on these long hard drives bumping over Majorcan roads, Shirley and Lenny would sing for me the Andrews Sisters with one sister missing. Well, to write about me without you would be like that." Game, set, and match, Rosamond Bernier.

The solitary sentence "I had a secluded and friendless childhood" is all that Russell is willing to say about his early years—a subject his friends have never heard him discuss. He will, however, explain the reason for his isolation. "Until I was grown up, I could hardly speak at all, you see, which restricted my social opportunities. I was thought of as some kind of freak. Whatever fluency I have in writing," he adds, "was powered by my lack of fluency in speech. It was so bad in school that I decided I just had to write—that or go begging in the street."

Art critics are not generally known for beautiful writing, but Russell is an exception. Simple and direct, his prose seems nonetheless to dance, as though each sentence were buoyed by a musical phrase. Like Rosamond, he's a popularizer who never condescends. "I think of my role as part entertainer, part evangelist," he says, though this description best fits his newspaper work and the sonorous pronouncements in his broad survey, The Meanings of Modern Art. He has also written a stack of scholarly books, most of them on the work of individual artists, that secured his reputation as an art historian. His study of Seurat, published in 1965, has been in print ever since. "It's the best book on Seurat," says author John Richardson, who welcomes Russell's retirement from The New York Times—"Now John will have time to write the books he should have been working on all along."

When Russell first wrote for L'Oeil in 1956 he was the author of four books, two of them about British art, and an esteemed critic. He was married for the second time, and the father, by his first wife, of a ten-year-old daughter. He supplemented his tiny salary from The Sunday Times by translating French books, among them Claude LeviStrauss's Tristes Tropiques and Andre Gide's Thesee. "When I first met Rosamond I was totally captivated," he says. "It was, however, totally hopeless. She was an important figure in the Paris world. I was a starving critic in London. In comparison with her, I was nobody." Indeed, though she had always admired his writing, she insists that "it never occurred to me to think of him personally—never." And so for a dozen years and more, through the end of his second marriage and six years into another relationship, Russell carried with him a passion undeclared and, on Rosamond's side, unsuspected.

Until one evening in London, in September of 1973, when John Russell came to take Rosamond out to dinner. He arrived alone (his girlfriend was in Spain at the time) at the apartment of Roland Penrose, founder of London's Institute of Contemporary Arts and a great collector, where Rosamond was staying. "I opened the door," Rosamond recalls, "and he fell into my arms and said, 'Didn't you know I've been in love with you for fourteen years?' " A few days later, when she accompanied him to Scotland for the Edinburgh Festival, he asked about her lecture schedule for the coming season; she mentioned the first date. "And then," says Rosamond with the gusto that drives her lectures, "he asked, 'Don't you think we could be married by then?' I said, 'By God! I thought you were married!' I thought he was married to his girlfriend, you see—I was absolutely astounded when he said no. From then on he never let go of the idea of marrying me."

Rosamond demurred—"I had absolutely no intention of marrying him or anybody"—and urged Russell not to upset his domestic arrangements, advice he ignored entirely.

Two years later, on a broiling day in May, two hundred friends gathered for the wedding at Philip Johnson's "glass house" in Connecticut. Johnson played the role of the bride's mother and father and planned every detail of the ceremony; Aaron Copland gave Rosamond away; Leonard Bernstein's wife was the matron of honor; Pierre Matisse was the best man; Arthur Gold, Robert Fizdale, and Ashton Hawkins were ushers. Irene Worth read Shakespeare sonnets and a passage from Congreve. As Rosamond once told a reporter in a moment of enthusiasm, "Most of our friends were there, from Geraldine Stutz to Jasper Johns."

As her husband might say, "Worthy of Fellini"—and indeed, the lurching, hectic plot and carnival of personalities seem to fit. But the ending, a love story that fuels a success story, is too improbably happy for the movies.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now