Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

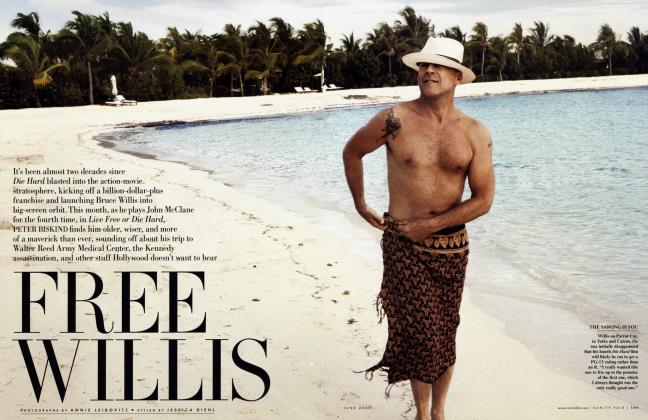

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE MESSIAH COMPLEX

Rabbi Moshe Levinger is Israel's John Brown, a fanatic willing to martyr himself for the right of the Jews to rebuild an ancient civilization on the occupied lands of the West Bank. His core of zealots may be small, but he has lethal significance in the renewed hopes for peace. ROBERT I. FRIEDMAN reports

ROBERT I. FRIEDMAN

Unto thy seed will I give this land.

—God’s promise to Abraham, recorded in the Book of Genesis

As Secretary of State James A. Baker shuttles between Middle East capitals on an elusive quest for peace, a little-known Israeli rabbi wields the power not only to sabotage any negotiations but also to ignite an apocalypse of biblical dimensions. Though he has never been the subject of an indepth profile in the Western media, Rabbi Moshe Levinger is acknowledged to be the father of the controversial West Bank settlement movement, a man who plays by a set of rules that were written during the age of the Prophets.

While he and his disciples use sophisticated computer programs to track the rapid growth of the settlements, their dream is more than two thousand years old: to found a messianic Jewish kingdom on lands where King David once wrote the Psalms and led his people into war. To protect thensacred enterprise, they have repeatedly vowed to take up arms against any Israeli government that agrees to trade land for peace with the Arabs. ‘ ‘Any Israeli government that moves seriously toward peace will be confronted by violent and ruthless opposition from within the settlement movement,” says leading Middle East expert Ian S. Lustick, who has worked as an analyst on West Bank affairs for the U.S. State Department, ‘ ‘and Rabbi Levinger will be the prime mover. ’ ’ Just last month Levinger, who has served prison time for killing an Arab shoe-store owner and for various assaults, was arrested again for shooting at Palestinian stone throwers in Jerusalem’s Old City. Levinger and ten of his followers had been protesting “inadequate security” in the Muslim quarter, where a number of Jews have been stabbed to death by Arabs.

Despite Levinger’s run-ins with the law, his attorney, David Rotem, himself a prominent West Bank settler, says the rabbi is a “visionary leader.” And Israeli housing minister Ariel Sharon calls Levinger and his wife “true heroes of our generation.” But he has been dubbed “Israel’s foremost fascist’ ’ by The New Republic, hardly an Israel-bashing magazine. And Israeli novelist and liberal intellectual Amos Oz has called Levinger the high priest of a “cruel and obdurate sect [that] emerged several years ago from a dark comer of Judaism.” Levinger’s “ultimate goal,” declares Oz, “is not to wipe out Arabs but rather to wipe out the State of Israel and proclaim in its stead the Messianic and insane Kingdom of Judah.”

For better or worse, Rabbi Moshe Levinger is arguably one of the most significant figures to emerge from modem Zionism since Israel’s strong-willed first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion. When Levinger founded the Jewish settlement in Hebron on Passover 1968, there were virtually no Jewish civilians living on the West Bank, which was captured by the Israeli army from the invading Jordanian Legion in June 1967. Today, there are more than 140 settlements and 100,000 settlers in the Occupied Territories, and the numbers are surging dramatically, fed by immigrating Soviet Jews and tens of thousands of secular Israelis who have been attracted by generous government subsidies and lower taxes. “What is happening in the Occupied Territories,’’ a senior American official in Israel told me, “is the systematic dispossession of [the Palestinian] people from their land.’’

James Baker, who has angrily singled out the settlements as “obstacles to peace,’’ flew to Israel soon after the Gulf War ended to pressure Yitzhak Shamir’s hardline government to make territorial concessions—something the cagey prime minister has repeatedly said he would never do (“Not one inch,’’ he declares). If Shamir’s position weren’t already clear, the prime minister approved the dead-of-night construction of a new settlement on the eve of Baker’s third post-Gulf War visit. “It was,” complained left-wing Knesset member Yossi Sarid, “like putting a bomb in the American secretary of state’s plane.”

Daniella Weiss, a Levinger protegee who helped establish the community, told me she is unfazed by American criticism. “The soil is holy and belongs to the Jews,” says Weiss, who insists the three-and-a-half-year-long intifada would have quieted down long ago if George Bush hadn’t refused to veto several U.N. resolutions condemning Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians. “I despise the president of the United States,” she says. “I could spit in his face and not feel regret if I lived to be one thousand years old. I’d have one thousand years of continued satisfaction.”

Even if a future Israeli government were willing to surrender any land, it would be faced with the problem of tens of thousands of outraged settlers. Mainstream settlement leaders have threatened to drag the country into civil war if they are forced to give up their homes. Aleph Yud, a settler newspaper, has warned that concessions would lead to “mutiny in the army, an armed uprising... and finally—Jew fighting against Jew.” In the last two years, Israeli press reports have exposed a shadowy right-wing underground connected to the settler movement called the Siccarim, which has firebombed the cars and homes of numerous Knesset members, journalists, and artists who advocate negotiating with the P.L.O. In the past, Rabbi Levinger has even publicly threatened to call on his followers to join him in mass suicide if the government evacuates the Territories. Just this April, Levinger declared that the only way he will leave the West Bank is in a pine box.

Together with several dozen armed followers, the blackbearded, fifty-six-year-old Levinger lives in the center of Hebron, a poor, drab, working-class city of 85,000 fiercely nationalist Palestinians. Nowhere on the West Bank is Islamic fundamentalism as strong or as inhospitable to outsiders as in Hebron, where there are no bars or movie theaters and where many Palestinian women wear long gowns and cover their heads with scarves. Likewise, there is no place in the Occupied Territories where Jewish fundamentalism is as uncompromising. Indeed, for many Orthodox Jews, Hebron is

a city that inspires almost as much passion as Jerusalem.

Anat Levinger, a pretty, twenty-one-year-old settler who is married to one of Rabbi Levinger’s sons, invites me to visit her small, two-bedroom flat in the Beit Hadassah building, the hub of Jewish communal life in Hebron. To enter the twelve-family Beit Hadassah complex, one must pass through an opening in a wrought-iron fence, which is surrounded by half a dozen bored-looking Israeli soldiers. The walls are festooned with posters of Rabbi Meir Kahane, the militant Jewish Defense League founder who was assassinated in New York last November. Levinger, who attended Kahane’s funeral in Jerusalem, has inherited much of the slain rabbi’s flock.

Anat, whose parents immigrated to Israel from North Africa in the 1950s, has lived in Beit Hadassah for about a year. She wears hip Birkenstock shoes, a purple blouse, black slacks, and a black head covering that glitters with silver stars. I remark that it must be quite dangerous to live in such unfriendly surroundings. “In Tel Aviv it’s dangerous, too,” she says, smiling sweetly. She adds, however, that the settlers have as little to do with the Arabs as possible. “I try not to buy food from Arabs. They need money and they might use it to buy bombs. But sometimes if I need to make something for dinner in a hurry I buy from them. ’ ’ She stands to peek out a window at the narrow road outside, which is crowded with Arab men in checked kaffiyehs and long flowing robes. “The city is dirty and it is dangerous. Sometimes I look out at the filthy streets and buildings and I get depressed. But the Jewish people need to live here. God will take care.”

Like an Old Testament prophet, it is Rabbi Levinger who dispenses eye-for-an-eye-style justice in Hebron. As far as he is concerned, any act of Arab defiance—whether it is a stone hurled at a passing Jewish car, a heated exchange of words between Arab and Jewish shoppers, or simply a malevolent glare—brings dishonor to the people of Israel if it goes unpunished. When a Palestinian boy flirted innocently with Levinger’s fifteen-year-old daughter, Levinger’s Americanborn wife, Miriam, called the Israeli army and had the boy arrested. “I don’t want any romances,” she said. ‘‘I want my children to remain Jewish.” And when Levinger’s thirteen-year-old daughter was teased by Arab girls, Rabbi Levinger became uncontrollably violent.

w Levinger put his hands around the throat of my [seven-year-old] daughter and tried to kill her.

•The way to destroy a peace agreement is clear,’ says Margalit. ‘Blow up the Dome of the Rock mosque. •

That was when Abdul Rahman Samua found out what it’s like to be the object of Rabbi Levinger’s wrath. Samua lives in a dung-colored stone house built during the Crusader era near the Beit Hadassah building on A1 Shuhada Street—“the Street of Martyrs”—named in honor of Palestinians killed by Israelis during the intifada. A small, round man with a soft, childlike voice, he owns a tiny vegetable stall in the souk, a grimy warren of meat, fruit, and vegetable shops that winds through the heart of the city. One afternoon in the spring of 1988, he closed the metal shutters on his shop and walked the few blocks home for lunch and an afternoon nap. Suddenly, Samua was jolted awake by screams. He came out of his bedroom to find Rabbi Levinger standing in the middle of the living room beating Samua’s wife and children while three armed settlers watched. “Levinger put his hands around the throat of my [seven-year-old] daughter and tried to kill her,” Samua told me matter-of-factly. When his nine-

year-old son intervened, the rabbi punched the child in the eye, then twisted and broke his arm. Samua’s wife, a big woman, scooped up her daughter, holding her tightly. “Levinger beat my wife on her back with his fists. It all happened in a matter of seconds.”

Alerted by the commotion, an Israeli soldier stationed on Samua’s roof scrambled down a ladder, entered the home, then quickly called for backup. (Soldiers have been posted on Samua’s roof since May 1980, when Palestinian terrorists, hurling grenades and spraying automatic-rifle fire, cut down six young yeshiva students in front of Beit Hadassah as they were returning from Friday-night Sabbath prayers at a nearby synagogue.) By the time a jeepload of Israeli soldiers pulled up in front of Samua’s home, Levinger was shouting

for someone to fetch his pistol. Levinger’s daughter and a pack of her friends, teenage girls in white blouses and black skirts, stood in the front doorway, egging the rabbi on. The Samuas’ television had been kicked in, and the dining-room furniture had been smashed into kindling. Levinger refused to budge, calling one Israeli soldier who tried to shove him outside “a P.L.O. agent.” “THIS IS MY HOUSE!” screamed Levinger. “THIS IS MY HOUSE!”

The army finally negotiated a retreat. Levinger agreed to go if soldiers put the Arab family in a bedroom so he wouldn’t have to bear the ignominy of being forcibly evicted from a Palestinian’s home in front of the owners. Levinger told the press, “I won’t behave like Jews in the Galut [Diaspora] who say it’s raining when a Goy [Gentile] spits at a Jew. I won’t let that happen in Israel.” Yisrael Medad, a settlement leader from Shiloh on the West Bank and a friend of Levinger’s, explains, “The fact that an Arab insulted a Jewish child after we’ve ruled Judea and Samaria for twentythree years was for Rabbi Levinger simply intolerable. It was an assault on Jewish sovereignty and honor.”

Palestinians also have a keen sense of honor, but Samua told me that he was too afraid to press charges. It was the Israeli military officers investigating the incident who insisted he bring Levinger to trial. “About eight months later, the Israelis sent a police car to my house and drove me to a Jerusalem court,” recalls Samua. After a brief trial, Judge Yoel Tsur acquitted Levinger on charges of assault and of

insulting an Israeli soldier. (The judge rejected testimony from the Samua family, saying they were “interested parties.”) In dismissing the testimony of the soldier who was the first to enter Samua’s home—and who corroborated much of the Arab family’s account—the judge ruled that once the soldier had left his rooftop post, he was no longer officially on duty. Tsur even acquitted Levinger of trespassing, ruling that when he barged into Samua’s home, it was as a neighbor visiting a friend. The state prosecutor appealed to a three-judge appellate court, which in an extremely rare action overturned Judge Tsur’s ruling, criticizing him for blatantly disregarding evidence, and convicted the rabbi of assault.

Levinger was sentenced to four months in jail on January 14, 1991, the day the world counted down the hours to the Persian Gulf War. When the sentence was read, Levinger bounded over the defense table, shrieking that the court was a tool of Yasser Arafat. His attorney, David Rotem, dragged him outside. The rabbi was sentenced to an additional ten days for the outburst. Some time later, Samua says, he was closing his shop when three burly settlers wearing knitted yarmulkes and brandishing rifles and nunchakus beat the vegetable seller unconscious.

Rotem, who admitted to me that he was “extremely embarrassed” by Levinger’s behavior in court, attempted to explain his client’s actions during a recent interview one afternoon in his Jerusalem office. “Rabbi Levin^ ger,” Rotem began in his basso profundo voice, “doesn’t wake up on Sunday morning at eight A.M. and decide, Well, today I’m going to assault an Arab or call soldiers names. He gets up on Sunday morning and decides, Now I’m going to do something very important for the state of Israel.” The problem, says Rotem, is that when he believes the honor of Israel is sullied, he sometimes loses control.

“What motivates him? Judaism, Zionism, and the state of Israel,” Rotem says, answering his own rhetorical question. “He has no other interests. Not money, not property. The guy doesn’t have a penny. His wife has an uncle who has been lying in a Jerusalem hospital for more than two years. Rabbi Levinger visits him every day. He feeds him, he cleans him. He’s not a rich uncle. Rabbi Levinger is not waiting for an inheritance. It’s just the way he is.”

Understandably, Rotem doesn’t like to talk about Levinger’s dark side. There was the time when the rabbi let loose Doberman pinschers on Arab demonstrators. And there was that wild afternoon not long ago when he gunned down an Arab shoe-store owner in a fit of hysteria. But more about that later.

One morning last November, I knocked on Rabbi Levinger’s door at eight A.M., hoping to speak to a man who has a notoriously low regard for the Western media. Levinger flung open the door and asked what I wanted. He had a pistol strapped on his hip and an Uzi slung at his side. Since no one in Israel has a reputation for being pushier than Levinger, I think he appreciated my surprise raid. He granted me an interview later that day. (It was, however, vintage Levinger—long on rhetoric and short on substance.)

I met the rabbi again last April during Passover in the Cave of Machpelah, the final resting-place for Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and their respective wives. Abraham bought the cave from the Canaanites for four hundred silver shekels some four thousand years ago. The cave is now in the bowels of a great, sand-colored stone fortress, which was built by Muslims—who also revere the patriarchs—during the Middle Ages. Levinger was sitting at a wooden table in a musty, dark chamber called the Hall of Jacob, bent over a Hebrew prayer book, apparently deep in meditation. Actually, he was dozing. He had been released the day before from Eyal Prison in central Israel, where he had served ten weeks of the four-month sentence for assaulting the Samua family. Levinger awoke from his nap and leisurely walked outside

to an open courtyard, where he stood in the sun against a thick stone wall. Once again I noticed that Levinger is an extremely odd-looking man. Tall and gaunt, with a skulland-crossbones face, he has an unforgettable appearance that has become part of his political persona, and has been used by the Israeli left to vilify him. (“His features are so repugnant that he looks like an anti-Semitic caricature in Der Sttirmer,” says Avishai Margalit, a professor of philosophy at Hebrew University in Jerusalem and a leader of Peace Now.) Levinger, who appeared more self-absorbed than usual, didn’t seem to recognize me. (His own friends call him an “astronaut” because he is often so spacey.) But as soon as I asked him what the government should do to improve security for the settlers, he was off and running. “Every day,” Levinger began, “hundreds of stones are thrown at the army and Jews traveling the streets of Judea, Samaria, and Gaza. The government has the power to quiet the Arabs, but lacks the will to do so. Perhaps we need General Schwarzkopf to silence the Arabs,” he said, a faint smile momentarily cracking his stem, Old Testament visage. As far as Levinger is concerned, the Palestinians have no national rights whatsoever. “The Arab is interested in his rug and his house,” he once told the Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz. “National sovereignty for the Palestinian people is a Jewish invention.” To me he said, “This land does not belong to the Palestinian people. In all its history it has belonged to the Jewish people. And because it is our place, we have to build more settlements and bring more Jews to live in Eretz Yisrael. The Arabs don’t understand that our connection to Hebron is no less strong than it is to Tel Aviv. If Diaspora Jews think Hebron is part of the ‘Occupied Territories,’ they won’t move there. And if the Arabs don’t stop the intifada, they will be transferred [the euphemism in Israel for expulsion].”

Continued on page 134

Continued from page 99

Rabbi Levinger

The rabbi broke away to greet some of the thousands of Orthodox Jews who had been arriving in chartered buses to commemorate Passover at the tomb of their forefathers. Each bus was chaperoned by two Israeli-army jeeps, one riding up front, the other in the rear, like scouts protecting a wagon train crossing hostile Indian country. Most of the worshipers were poor Sephardic Jews from the increasingly crack-infested slums of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. They came to pray, eat a picnic lunch on the cave’s sparse lawn, and then return home before dark across what Israelis call “the line of fear,” the invisible border that separates the West Bank from Israel. Like a proud proprietor, Levinger welcomed his “guests” at the top step of the huge structure before he and several dozen settlers, all bearded and armed, formed a circle in the courtyard and began to sing and twirl like whirling dervishes in joyous celebration of the Jewish people’s deliverance from bondage in Egypt more than three thousand years ago. “The people of Israel are not afraid!” cried one of his followers.

Levinger left the Cave of Machpelah in the company of two burly bodyguards. One, wearing a brightly colored knitted yarmulke, aviator sunglasses, and carrying an Uzi snug against his hip, looked like a young Ernest Borgnine. I wasn’t sure if the bodyguards were there to defend Levinger from a vengeful Arab or to make sure Levinger didn’t provoke a fight and wind up back in jail. Later, I asked a guard what it was like protecting the famous rabbi. “He likes to spend time playing with his grandchildren,” he said, eyeing me suspiciously. “And his entire

family came to his house in Hebron for the Passover Seder. He doesn’t seem to be the kind of man the media describes him to be. He’s not going around picking on people. ’ ’

Rabbi Moshe Levinger was bom in Rehavia, an upper-middle-class, predominantly German-Jewish neighborhood in Jerusalem, in 1935. His father, a Hasid, was a neurologist from Munich who had brought his family to Palestine in 1933, the year Adolf Hitler was named chancellor of Germany.

The Levinger family had more than its share of geniuses, eccentrics, and crackpots. One uncle founded the mathematics department at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Levinger’s aunt roamed the streets of Jerusalem in the late 1940s and early 1950s, mumbling passages from the Cabala, a collection of Jewish mystical thought. “Everybody knew her,” recalls Danny Rubinstein, the Arab-affairs correspondent for Ha’aretz, who, with other children, followed her around. “She used to repeat, ‘It’s all one connection, it’s all one connection,’ so we called her One Connection.”

Moshe was a sickly child who reportedly suffered from crippling bouts of depression. According to Koteret Rashit, an Israeli newsmagazine, he spent some of his youth in a Swiss sanitorium. In an interview with a religious newspaper, his father, Eleazer, said his son “was never physically strong, but even as a youngster it was apparent that he was a person of great spiritual stature.” He explained that Moshe compensated for being “small and weak” by being “quick and diligent” in his religious studies.

Moshe volunteered for the Israeli army when he came of age, even though youth engaged in Torah studies are exempt from military service. For a while, he served in a reconnaissance unit, though most of his time was spent guarding border villages. Following the army, he began religious studies at Yeshiva Mercaz Harav under Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, one of Israel’s most charismatic rabbis. Kook, who believed that Zionism is part of God’s plan, taught that the Jewish return to Israel and the flowering of the land heralds the beginning of the messianic age. It was a selfactualizing kind of messianism in which one could push along the divine process simply by following God’s commandments. The most important commandment, declared Kook, was settling the land, which should be defended at any cost.

After becoming an ordained rabbi, Levinger worked for a number of years as a shepherd on a religious kibbutz in the Gal-

ilee. He was known for his unkempt beard and sloppy appearance more than for his religious knowledge. A taciturn, humorless man, he was considered an eccentric loner burning with a visionary fire—he was convinced that he would witness the rebirth of the Jewish kingdom. More than that, he was sure that he would play a key role in making it happen. “He believes it is his duty—a mitzvah [commandment] from the Torah [to rebuild the ancient kingdom of Israel],” says his brother, Yaacov Levinger, a professor of Jewish studies and philosophy at Tel Aviv University. “This, for him, is a dogma, which he believes very deeply.”

In 1959, Levinger met his future wife, Miriam, a highly intelligent young woman from New York, who was studying nursing in Jerusalem. Miriam was the daughter of Hasidic parents who had journeyed from Hungary to the East Bronx. Their neighborhood, like many in New York, was rapidly changing from a comfortable Jewish enclave of Yiddish-speaking, bagel-and-lox-eating immigrants to one dominated by poor African-Americans and Hispanics. Two of her older brothers ran nightclubs. Miriam often visited the clubs to hear jazz greats like Lena Home. Still, Miriam has said, she hated her childhood. She was scared out of her wits by street crime. Like many American Jews who grow up with a sense of dislocation, she found her purpose in Israel, where she would become a settlement leader in her own right. If Moshe was a lofty visionary, then Miriam was of true pioneering stock, tough, dutiful, and pragmatic. She bore him eleven children, clothed and fed them, while making sure that her husband—a man inattentive to mundane things like personal hygiene and food—functioned properly. “My role,” she has said, “is to make it easier for my husband and to fulfill the mission given to me by the Torah.”

Levinger might have remained an obscure rabbi if not for the Six-Day War. The Israeli victory unlocked pent-up messianic passions in many Orthodox Jews as they were reunited with the core area of ancient Israel, the West Bank, which they refer to by the biblical names Judea and Samaria. They regard this as their historic homeland; the ancient Hebrews were people of the hills, and Jerusalem and Hebron were their most venerated cities. (The area making up pre-1967 Israel—the dagger-shaped strip of land along the coastal plain on the Mediterranean—had belonged to other peoples, the Canaanites, the Jesubites, the Phoenicians.) When Israeli tanks stormed the Samarian highlands and swept into the Judean desert in June 1967, many Jews felt that they were coming home.

Three weeks before the outbreak of the war, Rabbi Kook had a vision. It was Israeli Independence Day, and in his holiday sermon the seventy-three-year-old rabbi spoke of his intense longing for Judea and Samaria. “Where is our Hebron? Do we let it be forgotten? And where are our Shechem [Nablus] and our Jericho? ... Can we ever forsake them? All of Transjordan—it is ours. Every single inch, every square foot. .. belongs to the land of Israel. Do we have the right to give up even one millimeter?’ ’ The speech was later seen by his followers as a prophetic call to settle the newly conquered lands.

On the sixth day of the war, as Israeli troops took the Wailing Wall—the remnant of Herod’s temple—one of Kook’s students climbed to the top row of stones and unfurled the Israeli flag. Soon after, soldiers in a captured Jordanian jeep drove Kook to the Wall, in East Jerusalem’s Old City, under the crackle of sniper fire. “We announce to all of Israel, and to all of the world, that by a divine command we have returned to our home, to our holy city,” Kook proclaimed. “From this day forth, we shall never budge from here! We have come home!”

Ten months later, Kook sent his prize pupil, Moshe Levinger, to resettle Hebron, where the Jewish people had lived for centuries until 1929, when Palestinians slaughtered sixty-nine Jews, many of them elderly Torah scholars.

What began in messianic fervor ended in organized terrorism. It also changed the landscape of Israel. On April 12, 1968, thirty-two Jewish families led by Rabbi Moshe Levinger moved into the Park Hotel in downtown Hebron in defiance of official Israeli government policy, which then barred Jews from moving into West Bank Arab cities. They came to Hebron, they said at the time, to celebrate Passover; they never left. “When I traveled to Hebron, there awakened within me raging spirits that did not give me peace,” remembered Levinger.

One month after the settlers occupied the Park Hotel, a deeply divided Israeli Cabinet voted to let the group stay in Hebron, moving them into a military compound. Two years later, the government established the settlement of Kiryat Arba on the stony slopes overlooking Hebron. It was a major victory for Levinger, who had forced the Israeli government to underwrite a Jewish settlement in the heart of a heavily populated Arab area. Until

then, the Labor Party had built settlements primarily for security purposes in strategic areas far away from Palestinian towns. Those settlements, according to such leaders as Deputy Prime Minister Yigal Allon, were to be used as bargaining chips in future peace talks.

The issue grew more explosive after the 1973 Yom Kippur War when Rabbi Kook helped form the mystical-messianic settlement movement, Gush Emunim (“Bloc of the Faithful”). Its members, often led by the peripatetic Levinger, would arrive in darkness at a desolate hilltop in a milelong caravan of beat-up trailers. When the army came to expel them—as it almost invariably did—the right-wing parties would charge the Labor government with the betrayal of Israel.

The most violent clash between the government and Gush Emunim occurred over Sebastia, an abandoned Turkish-railroad depot near Nablus. After one pitched battle between soldiers and settlers in which rocks and rifle butts were used, Defense Minister Shimon Peres flew to the site by helicopter and burst into the tent that Levinger was using as his “war situation room.” Peres called Levinger a “Napoleon,” and the rabbi stormed out, rending his white dress shirt in the sign of Jewish mourning—and a call for mass hysteria. The Labor Party was up for reelection and was afraid to alienate the religious parties, their traditional allies; Peres finally caved in to Levinger.

But the moderate Labor Party lost to Menachem Begin’s Likud Party in 1977. It was an earthquake in Israeli politics. Immediately after his election, Begin journeyed to Sebastia, by then renamed Elon Moreh. Holding a Torah scroll aloft, Begin promised to establish “many more Elon Morehs!” Soon, dozens of virgin West Bank hills were bulldozed and replaced with neat single-family homes with red tile roofs and small gardens—a great luxury for those who live in Israel’s crowded cities.

But Levinger was not interested in living on some distant hill. His unshakable dream was to transform Hebron into an exclusively Jewish city. At three A.M. one March morning in 1979, Miriam Levinger and forty women and children marched down the slope from Kiryat Arba into Hebron’s Casbah and occupied Beit Hadassah, a derelict Jewish health clinic. “Hebron will no longer be judenrein," she proclaimed in a television interview. The Begin government was thrown into a major political crisis. Though he had been elected on a prosettlement platform, Begin’s security services warned him that it was impossible to protect a handful of Jewish families in the

heart of an intensely hostile Arab city. He ordered the army to prevent the squatters’ husbands from joining them, and to stop them from bringing in furniture and other household items. The government hoped that the primitive conditions would drive the women, many of whom were pregnant, back up to Kiryat Arba.

“There was a shortage of water, the sanitation was very, very bad, and one or two of the children were very sick,” remembers Brigadier General Fredy Zach, military governor of Hebron from 1979 to 1981 and now the deputy coordinator of the Occupied Territories. “But the Levingers told me they would never move. I remember, that Hanukkah, seeing all the menorahs with candles in each window in Beit Hadassah—and I remember the light in Rabbi Levinger’s eyes. He told me, ‘Fredy, for me, the real holiday is seeing the menorah lit in Hebron.’ I told myself, That’s it. It’s finished. They are going to stay here in spite of all the problems.”

Zach, then a thirty-two-year-old captain, says he has witnessed two Levingers—the respected spiritual leader and the madman. Once, after Zach ordered an Arab girls’ school closed because the students had thrown rocks at soldiers, Levinger demanded that the building be turned over to the settlers. “I told him, ‘Rabbi Levinger, I can’t give you a building on my own initiative. If you have problems, go and talk with the politicians.’ He went crazy. He insulted me and called me a criminal. But a few hours later he apologized, saying, ‘I’m sorry, sometimes I go out of my mind.’

“The settlers believed they were contributing to Israel’s security,” says Zach. “They still believe it. But for us it was not a contribution, because we guarded them and it was very difficult.” At 7:10 P.M. on May 2, 1980, in the Cave of Machpelah, religious Jews sang “Adon Olam,” “Master of the Universe,” the final hymn of the Friday-night Sabbath service. Afterward, several dozen worshipers walked the kilometer from the cave to Beit Hadassah for the Sabbath meal. As they entered the narrow street in front of the building, Palestinian terrorists opened fire with assault rifles and hand grenades. Six yeshiva students were killed and sixteen wounded. “It was the most devastating terrorist attack we ever faced in the Territories,” says Zach, who was at the scene within minutes.

The following evening, a group of rabbis and community leaders decided to set up a terrorist underground that would strike fear into the hearts of the local Arabs. “I met with Rabbi Moshe Levinger, and I expressed my view to him that for this kind of task pure people should be selected, people who are deeply religious, people who would never sin, people who haven’t got the slightest inclination for violence,” said Menachem Livni, who would head the Makhteret—the Hebrew word for underground—which became the most violent subversive organization in Israel’s history.

Rabbi Levinger

On the morning of June 2, 1980, one month after the murder of the yeshiva students and at the close of the traditional thirty-day period of Jewish mourning, squads of Levinger’s disciples placed bombs in the cars of two Palestinian West Bank mayors, grievously wounding both men. A grenade placed on the garage door of the Palestinian mayor from El-Bireh blinded an Israeli-army bomb-disposal expert. In July 1983, shortly after an Arab stabbed to death a Jewish seminary student in Hebron, members of the Makhteret, including one of Levinger’s sons-in-law, burst into the courtyard of the Islamic College in Hebron during a noon lunch break, tossing a grenade and spraying machinegun fire. Three Palestinian students were killed and thirty-three were injured.

The underground attempted its most sensational act on Thursday, April 26, 1984, when members attached explosive charges to five buses parked beside the homes of their Arab drivers in East Jerusalem. One of the buses, which belonged to the Klandia Bus Company, had been chartered by a German tour group. The explosives were set to go off at 4:30 P.M. on Friday, when few Jewish cars would be on the road because of the approaching Sabbath. Early that morning, agents of Shin Bet (Israel’s F.B.I.) who had infiltrated the Makhteret, dismantled the bombs and arrested nearly three dozen settlers. After four years the underground had finally been caught red-handed.

In a signed confession, Livni told Shin Bet that seven prominent rabbis, including Levinger, were actively involved in the underground and had “blessed” the attacks on the mayors. Levinger was arrested soon after Livni’s confession. According to Dan Be’eri, an underground member, Levinger agonized over whether he should also confess as a show of solidarity with his jailed comrades. But the other underground members persuaded Levinger to maintain his innocence, fearing that his admission would cripple the settlement movement. Levinger was released from jail after ten days. “Shin Bet didn’t push him too hard, and we influenced him not

to speak,” recalls Be’eri, who is now the director of several Orthodox girls’ schools in Israel. “I have the feeling the government didn’t really want to try him. It would have been a huge scandal to put the leader of the settlement movement on trial.”

Be’eri had been arrested for his role in the underground’s aborted plot to blow up Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock mosque —the site where the Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven on his winged charger. It was easily the most terrifying scheme hatched by the underground. By destroying the mosque, the plotters hoped to sabotage the Camp David accords and block Israel’s scheduled withdrawal from the Sinai. Several of the plotters actually believed the bombing would usher in the messianic age. Most probably, the destruction of the famous mosque would have set off a chain of events resulting in a bloodbath for Jews around the world. The plan was eventually abandoned, not out of fear of the consequences, but rather because Levinger didn’t think the timing was right. “Levinger said that he would not try to prevent the group from carrying out such an operation,” Be’eri has said, “although he personally believed the nation had to be prepared in advance for such a thing.”

In July 1985, a three-judge court in Jerusalem convicted eighteen members of the underground, handing out prison terms ranging from four months to life. Today, after years of intense lobbying, the entire underground, including Levinger’s son-in-law and two others serving life sentences, has been released from jail. “There is no doubt that Levinger was the master of the underground,” Ha’aretz’s veteran correspondent Danny Rubinstein told me. “All the people in the underground were his followers. Five or six of the Makhteret were with him in the Park Hotel. One of them is his son-in-law, and three of them were his next-door neighbors.” (Despite the confessions of Livni, Be’eri, and others, attorney David Rotem calls charges that Levinger was part of the underground ‘ ‘ rubbish. ”)

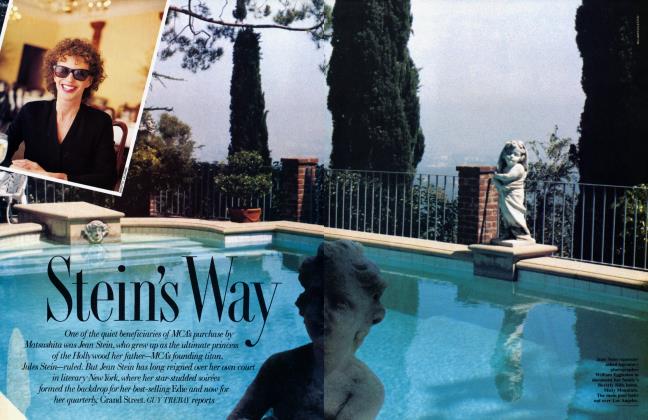

In 1982, Rabbi Levinger helped to set up the Hebron Fund, a charitable, taxexempt New York foundation that raises money to acquire real estate. At the fund’s third annual dinner, held last May in honor of the Levingers at the Sheraton Meadowlands Hotel in East Rutherford, New Jersey, across from Giants Stadium, Miriam compared her childhood in New York with her children’s in Hebron. “I grew up in the East Bronx and I was a very fright-

ened Jewish child,” she told the five hundred or so guests. “I remember running away. And I see my children—the way they walk around Hebron, forty or fifty [Jewish] families in a city of 70,000 Arabs, and not so very friendly Arabs at that—and they walk around as if they own the market. .. . They are not afraid and they have no traumas and if they are asked, ‘What are you doing here?’ they say, ‘We are reclaiming Hebron. ’ And God promised us that one day we would do this!”

The black-tie event, whose guests included corporate raider Marc Belzberg and several members of the Reichmann family of Canada, owners of Olympia and York Developments Ltd. (one of the largest privately held real-estate companies in the world), raised nearly $300,000. The two previous Israeli directors of the Hebron Fund were convicted members of the Makhteret.

Rabbi Levinger couldn’t attend the gala in his honor—he was in an Israeli prison for killing an Arab shoe-store owner. “I’m sure my husband is very sorry he couldn’t be with you tonight,” Miriam said with a smile, prompting laughter. “He has his religious books and I’m sure he will be occupied for the next five months. I spoke to my mother-in-law and I think she’s a bit pleased because she told me now he’s going to eat regularly and go to sleep on time.”

Rabbi Levinger’s eating and sleeping habits had improved as a result of a wild drive through downtown Hebron on September 30, 1988. “I, my two sons, one daughter, and my granddaughter were in the car,” Levinger told a reporter. “They [a group of young Palestinians] threw hundreds of stones at us. My daughter is ten years old and my granddaughter three. All we did was to protect ourselves.”

Levinger claims he fired his pistol in the air from his Fiat window to scare away the stone throwers. But according to numerous witnesses, Levinger parked his car far from harm’s way and walked determinedly toward the demonstrators, firing his pistol indiscriminately. Ibrahim Bali, an Arab textile salesman, was buying new shoes for his daughters when he heard the shooting. He was standing outside a shop when a bullet tore through his shoulder. A bullet also ripped into the chest of Khayed Salah, who was about to close the metal shutters of his shoe store. The Israeliarmy company commander who witnessed the shooting said that after the rabbi fired his weapon he walked down the road screaming “You’re dogs” at Arab vendors, kicking over vegetable crates and flower containers. The officer said he grabbed Levinger’s trembling hand, and told him not to move. Levinger snarled back, “Leftist! Arab lover!”

Rabbi Levinger

Salah’s older brother, Khaled, is the well-to-do owner of a shoe factory. He lives in an exclusive Palestinian suburb of modem stone apartment complexes and modest homes, on a steep slope just outside Hebron, far from the crowded street where the shooting occurred. “I was working in the factory when somebody ran in and told me my brother had been shot,” Khaled, a neat, trim man wearing a gray cardigan and slacks, began. “I was shocked. I went to our shop, but he had already been taken to a hospital in Jerusalem, where he died.” On the day of the funeral, said Khaled, thousands of Palestinians converged on the central mosque, carrying his brother’s body, wrapped in a P.L.O. flag and surrounded by palm fronds. Suddenly, a helicopter appeared overhead and dropped tear gas. Then Israeli soldiers seized the body, and dispersed the Palestinians with batons and rifle butts. “They held the body for fortyeight hours,” Salah recalled bitterly. “They said we could have it back if we held a private funeral with no more than twenty mourners, none of whom could be men between the ages of fifteen and forty. ’ ’

Although settlers have killed at least forty-two Arabs during the intifada, only four other cases have been prosecuted. Seven months after Salah’s murder, Levinger was indicted on manslaughter charges. He claimed he was being persecuted by “[Israeli] leftists who want to destroy the settlements.” His colleagues mounted a vigorous public-relations campaign, lobbying Knesset members and picketing the courthouse. Nearly nine months into the trial, however, Levinger plea-bargained the charge down to criminally negligent homicide. On the day that he entered prison, he was carried through the alleyways of Hebron’s cramped Casbah on the shoulders of hundreds of his supporters, many brandishing assault rifles and singing the anthem of the West Bank settlement movement, “Am Yisrael Chai” (“The Jewish People Live”). He was sentenced to serve five months in prison but was released after just ten weeks.

I asked David Rotem why he’d advised the rabbi to accept a plea bargain. “Because Rabbi Levinger is a very difficult client,” conceded Rotem, who added that he feared Levinger would lose control in court if the trial continued. “Not that he

would have shot somebody,” Rotem explained, “but that he would have started his defense from the days of Abraham and gone on until the coming of the Messiah.

“Frankly, however, I was amazed [that he accepted the plea] because virtually everyone wants to be found not guilty. But Levinger told me, ‘Look, somebody was killed. I don’t know whether this man was actually one of the people throwing stones.’ Then he told me a story from the Talmud about an argument between God and Moses.” Although Moses wandered in the Sinai wilderness with the children of Israel for forty years, Levinger told Rotem that God would not let him enter the Promised Land, because he had killed an Egyptian. “You know, if Moses had to pay because he killed an Egyptian without permission from God,” Levinger told Rotem, “maybe I have to pay, too.”

Still, Levinger never expressed remorse to the Salah family. In fact, he even declared during the trial that, though he hadn’t killed anyone, he wished that he’d had “the honor of killing an Arab.” The remark was widely quoted in the Israeli press. Khaled says the short prison term Levinger received for killing his brother compounds his family’s grief. “When I see Levinger in the street today with a pistol and a rifle, what shall I do? There is a saying in Arabic, ‘If your enemy is the judge, to whom are you going to complain?’ ”

Perhaps to Dan Meridor, the forty-fouryear-old Likud minister of justice. Though a self-described hawk and staunch advocate of “Greater Israel,” Meridor is prosecuting cases brought by West Bank Arabs against Jews in record numbers—at considerable risk to his political career. “I don’t accept that you have to break the law in order to be a good Zionist,” he told me in a rare interview about settler violence. “There is no contradiction between my hawkish attitudes [on the Occupied Territories] and my basic belief in human rights and civil rights and justice and law and morality.” In February, Meridor said, right-wing extremists smeared graffiti on the front door of his Jerusalem apartment, calling him a “bleeding heart” and a “leftist.” “And when I indicted Levinger, I got threatening phone calls,” he said. One man called Meridor a “Kapo’ ’—the name given to Jews who helped the Nazis run the concentration camps.

Though Levinger’s popularity among the religious settlers remains strong, a growing number of movement leaders are beginning to distance themselves from him in the wake of his highly publicized legal difficulties and his nasty dispute

with Meridor. “I’d give Levinger money not to be our spokesman,” says Rabbi Benny Elon, a prominent right-wing settler whose father is a liberal judge on Israel’s supreme court. Others, however, remain steadfast. “In every revolutionary movement you have to have someone obtuse, stubborn, very single-minded, and Levinger is that person,” says settlement leader Yisrael Medad. “When we need to see the broad ideological picture we call on Levinger, who is the anchor, who gives us our sense of direction.”

Many Israelis fear that Levinger’s vision could lead the country to disaster. They are convinced he or one of his followers would commit a fantastically violent act if it could upend a prospective Israeli withdrawal from the Occupied Territories. “If there are peace talks, I have no doubt that a new [settler] underground will emerge,” says Hebrew University’s Avishai Margalit. “And the way to destroy a peace agreement is very clear: blow up the Dome of the Rock mosque. Then the whole world will be against us.”

Self-destructive messianism is not new to Jewish history. Masada immediately comes to mind. Masada is the ancient mountaintop fortress in the Judean desert near Hebron, where Jewish rebels held off a superior Roman force for almost two years. On the second day of Passover in A.D. 73, Roman legionnaires stormed Masada and found the Jewish defenders— 960 men, women, and children—dead. They had committed suicide rather than endure Roman captivity. The victorious Romans denuded the countryside. The surviving Jews were scattered across the empire. Even the name of Judea was changed—to Palestine. Ironically, many of his fellow countrymen opposed Masada’s rebel leader, Elazar ben Yair, who they believed was agitating not for political freedom but to express his esoteric religious beliefs. His fanaticism and that of the other Zealot groups throughout Judea put an end to the Jewish state for two thousand years.

To many Israelis, Rabbi Levinger is the direct descendant of ben Yair. Like a modem-day Zealot, Levinger insists that mysticism is a healthy part of the Jewish experience. “Zionism is mysticism,” he says. “Zionism will wither away if you cut it from its mystical-messianic roots. Zionism is a movement that does not think in rational terms—in terms of practical politics, international relations, world opinion, demography, social dynamics—but in terms of divine commandments. What matters only is God’s promise to Abraham as recorded in the Book of Genesis.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now