Sign In to Your Account

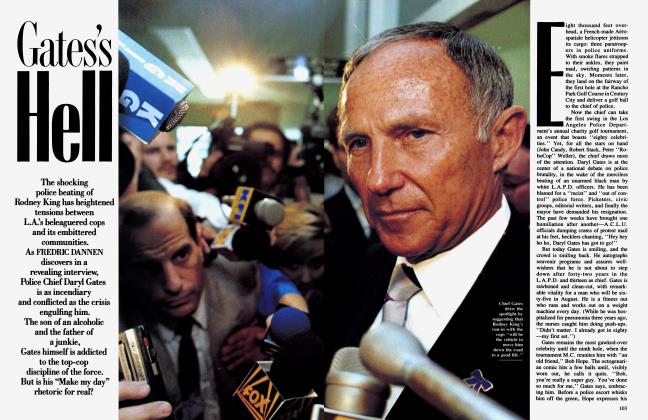

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBarnes Storn

Why was board president Richard Glanton so quick to call for de-accessioning works from the Barnes collection? And why was Whiter Annenberg his unlikely ally?

Before died his trustees gorical in and intact, with art his Albert 1951, instructions he struggled collection and wishes. C. left the original to Changes Barnes to private comply catekeep have occurred, however. In 1960 the Barnes Foundation was finally forced to open its doors to the public two days a week, and recently Knopf obtained rights to publish color reproductions of the collection. On February 28 of this year, the Barnes came under siege from within.

Richard H. Glanton, president of the Barnes Foundation, stunned the

Barnes's art advisory committee when he announced that the villa in which the collection was housed was falling apart and that the board was thinking of petitioning the courts for permission to sell a few paintings in order to make necessary repairs. As all of the experts at the meeting knew, such practice is condemned in the museum world.

Richard Feigen, the New York art

dealer and a member of the committee, said Glanton presented the petition as a fait accompli. "He didn't say, 'What do you think of this?' or 'How can I get money for this?' I said to him, 'You've got a bunch of professionals who've come here voluntarily and have contributed their time and effort to try to be of assistance and you haven't asked them a single thing.' Then he very, very sarcastically said, 'I'm all ears.' But it was clear he'd made his mind up what he wanted to do."

"This was not a last-ditch effort; this appeared to be a first- ditch effort," said Tom Freudenheim, the Smithsonian Institution's assistant secretary for museums, who was also at the meeting. Freudenheim had proposed bringing the straitened finances of the Barnes Foundation to the attention of the National Endowment for the Arts and the Nation-

al Endowment for the Humanities. Glanton showed no interest, Freudenheim recalled, even though he appeared to have no fund-raising strategy besides putting art on the block.

Glanton announced that his petition had the support of billionaire publisher and art collector Walter Annenberg, the former owner of The Philadelphia Inquirer. Early this year, Annenberg had been named honorary chairman of the

art advisory committee, but he was not present at the meeting.

Glanton then asked the committee members not to talk to the press about what they had discussed at the meeting before the petition came up for a hearing in late May (later postponed to August). Most members kept obediently silent in public, although in private they expressed dismay over the potential sale of art. They felt that a policy of deaccessioning would bring not only the Barnes but also Lincoln University, the black institution Barnes had left in control of his collection, into disrepute.

For the next four months, until the proposal to sell paintings was reluctantly withdrawn, those who foresaw the dismemberment of the extraordinary collection joined in a chorus of outrage.

Richard Glanton, the man who has given himself the mission of taking the Barnes "into the twenty-first century," is a Philadelphia corporate lawyer and a conservative Republican with a reputation for shrewdness, charisma, and charm. Those who know him well observe that he combines sure instincts for political hardball with homespun salesmanship. As one former colleague put it, "This guy could sell ice to the Eskimos." Glanton was an early fund-raiser for George Bush's presidential campaign, in return for which he is said to have expected a Cabinet-level reward. Running the Barnes, where Glanton has referred to himself as "chief executive officer," guarantees him a prominent place in the public eye and a potential power base.

Glanton admits that he has no background in art—none of the five Barnes trustees does. Until less than four years ago, Glanton had never seen the Barnes collection. Raised in rural Georgia, he studied law at the University of Virginia and worked for former Pennsylvania governor Richard Thornburgh before taking up private practice in Philadelphia. In 1985 he became a state-appointed trustee of Lincoln University; he also serves as the school's legal counsel. Questions about his qualifications to head a major art collection triggered an impatient response: "If you walked across the street and saw a gold coin, you would pick it up. Why? Hell, because you saw it. This is completely a fluke, my being on the Bames Foundation board, my being president."

In March, less than three weeks after the art-advisory-committee meeting, Glanton petitioned the Montgomery County Orphans' Court (a Dickensian term for a surrogate's court, specializing in trusts and estates) to override the strict bylaws laid down by Bames and allow up to fifteen paintings to be sold in order to raise the $15 million he said was necessary to modernize and operate the foundation. Glanton also requested permission to hold social events on the grounds, and to relax the restrictions on how funds from the Bames endowment can be invested.

A few jaded art-market insiders shrugged off any alarm, pointing out that museums frequently cull ''lesser works" from their "permanent" collections. Some of the country's most eminent institutions have recently sold masterpieces in order to acquire other works of art. However, such sales often elicit a justifiable uproar, as happened last year, when the Guggenheim auctioned off a major 1914 Kandinsky.

But the Bames case is unique. For one thing, a private collection that reflects the time, the eye, and the passions of the man who assembled it is an endangered species in the United States. Moreover, Barnes's ban on the sale of paintings was unambiguous. Also, in accepted museum practice, paintings should be sold only to buy other works of art; in the case of the Bames, no new acquisitions are permitted.

Edward J. Sozanski, the art critic of The Philadelphia Inquirer, stated the art world's general attitude toward Glanton's gambit: "Selling pictures is like burning the furniture to keep warm." The New York painter Leland Bell called the move "an absolute tragedy."

It was one of those rare occasions in the art world when hyperbole seemed to be justified, for immediately the sharks started moving in. Richard Feigen's gallery received predatory queries: "I got a call from some guy in Philadelphia whom I'd never heard of, saying, 'I've got $15 million on the table to buy some Bames paintings to take away the problem.' One of the most important collectors in the world called me from Switzerland and asked, 'Is there any chance of getting any of those pictures now?' " In May, The Independent, a London newspaper, reported that the

J. Paul Getty Museum had offered Glanton $3 billion for the Barnes collection, a rumor instantly denied by Getty officials.

The current Bames crisis dates from 1988, when Violette de Mazia, the foundation's director of education, died. With the departure the following year of the two remaining original trustees, four of the five seats on the board came under the control of Lincoln University. The chairman of Lincoln's board, Franklin Williams, an alumnus of the school and a former U.S. ambassador to Ghana, became president of the Bames. Richard Feigen, who was invited by Williams to join the Lincoln board, credits him with wishing to respect the integrity of Dr. Barnes's legacy. The small endowment and the Draconian restrictions imposed on it by the doctor, however, made it hard to fund operations.

Admission was one dollar, the galleries were open to a limited public only two and a half days a week, and the roof needed fixing. Feigen was determined that Lincoln should allay any fears in the art community as to its guardianship of such an important treasure. Lincoln was no less determined to consolidate its grip on the unfamiliar reins.

As a dealer, Feigen was immediately suspected of ulterior motives. Those in the art world who wanted contact with the Bames, however, saw him as a gobetween. The Bames board under Williams automatically rejected all requests to buy paintings, but pleas for loans and photographs continued pouring in from all over the world. Some requests were quite imaginative: the Los Angeles County Museum of Art offered to conserve paintings if it would then be permitted to exhibit them in its Fauve landscape show. That offer was turned down. So were the organizers of the extensive Seurat retrospective that moves from Paris to New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art this fall. Of the six Seurats in the Bames, only the masterpiece Les Poseuses is represented—in a black-and-white photograph.

In his determination to do the right thing, Williams was scrupulously cautious. He wanted a proper inventory taken, and a study made of the Barnes educational methods. Since none of the trustees appointed by Lincoln had any

experience in the field of art, Feigen urged Williams to name someone who did. To no avail. "The board did not want a non-Lincoln person there," Feigen said, "mainly because they did not want to lose control." Feigen then urged the creation of an art advisory committee, and the board agreed to this.

The art advisory committee included such members as Roger Mandle, deputy director of the National Gallery of Art; Kirk Vamedoe, director of the department of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modem Art; Anne d'Harnoncourt, director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art; and Tom Freudenheim. Feigen, who was also a member, says that no chairman was named, perhaps because Lincoln did not want an outsider to become the spokesman for the Bames collection.

By the time the committee had its first meeting, Williams was so ill that he was forced to participate by speakerphone. In May 1990, before the members had had a chance to reorganize the Barnes, he died of lung cancer. People close to Williams maintain that he kept Richard Glanton, general counsel to Lincoln University, at arm's length. They claim that Williams stood between Glanton and the seat on the Bames board that Glanton was known to covet.

After Williams died, Feigen says, he again attempted to persuade the board to appoint someone with a background in art to run the collection, but got nowhere. The dealer found himself outnumbered by Lincoln board members in Glanton's camp. In June 1990, Feigen was supposed to speak at a symposium at the L.A. County Museum, but he let it be known that he was prepared to cancel the California trip if the trustees were going to decide who would be named to the Bames board that weekend. He says he was assured that no decision would be made at that meeting. "After I got back, I learned that Glanton had been nominated to the board. Then I was encouraged to drum up opposition to Glanton by other Lincoln board members. It was obvious that I wasn't the only one who had reservations about him."

When Glanton became president of the Bames board later that summer, he told The Philadelphia Inquirer that he intended to "be very faithful and loyal to the indenture in administrating the foundation." Last fall he was the subject of an admiring profile in the Inquirer's Sunday magazine which described him as "a lifetime student of power," who ''never purported to know anything about art" and who would oversee change at ''one of the world's most eccentric, secretive and even paranoid cultural institutions."

"i 'm suprised You think the building is adequate," said Annenberg. "it reminds me of sunset Boulevard."

In May of this year, to justify his attempt to break Barnes's indenture, Glanton led a reporter and photographer from The Philadelphia Inquirer on a tour of the allegedly dilapidated galleries. He made the most of crumbling fixtures and structural wear and tear. At the end of the tour, he announced that his estimate for needed funds had risen from $15 million to $18 million.

Bames Foundation teachers and artadvisory-committee members conceded that certain repairs were needed, but they maintained that studies of security and climatic conditions at the Bames had not uncovered any critical neglect. What really worried them was the revelation that many of the renovations planned were not for the galleries, where the paintings hang, but for other buildings owned by the foundation. There were also rumors that a conference center and a parking lot had been envisaged. Glanton told a reporter that no conference center was planned.

JB s Glanton's projects accumulatJH ed attention and opponents, the |M only person with ties to the art I ■ world who continued to support Glanton wholeheartedly was IH Walter Annenberg. This seemed I ■ strange, in view of the tycoon's I wk insistence, in March, that the collection of fifty-three paintings he was donating to the Metropolitan Museum be permanently shown as a group, and that no paintings ever be lent or deaccessioned: "I would never sell a member of my family." If a future Met director had the temerity to put a paint-

ing in storage for any reason besides repair, Annenberg threatened, he would "get up out of my grave and hit the director over the head."

The Barnes collection apparently called for different treatment. Just after the petition was filed, Annenberg insisted that the Bames had no choice but to sell off works. "Where do you think they are going to get funding to do what's necessary?" he asked a reporter. "It would take them twenty years to raise funds."

Annenberg's advice seemed to confirm Glanton's vision of the art world, in which the Bames, he claimed, was at a clear disadvantage for raising money compared with other, more established museums with well-oiled development departments. "You know the pecking order and the way they fix their boards in terms of how they get their support. They don't even have sufficient funds to have endowments that would throw off enough operating cash to get them through these hard fiscal times," Glanton told me. "What am I to believe? That the very successors of the people who cursed and damned Bames in his life are totally committed to saving him in death? I find it ironic."

On April 17, the eighty-three-yearold Annenberg resigned from the art advisory committee, citing health reasons and adding, "I don't want to be around when there's a rhubarb going on with the advisory committee." (In the 1970s, Annenberg's eager support for Thomas Hoving's quixotic plans to head a multimillion-dollar communications center on the current site of the Metropolitan Museum's Wallace Wing created just such a "rhubarb," which the New York art world remembers grimly.)

Annenberg, however, did not resign before expressing his disdain for much of the Bames collection. ' 'They probably have about two hundred first-class paint-

a

ings," he commented.

"There are some great Matisses and some dogs. There are any number of horrible Renoirs and between twenty and thirty Renoirs that are first-class. To keep hanging all of that is ridiculous." He said the foundation's handsome limestone villa was a "rabbit warren." Meanwhile, Annenberg was donating $5 million to the Metropolitan Museum for elaborate galleries to house his collection.

"I have all pictures of great quality," Annenberg told The Philadelphia Inquirer when asked about any contradiction between his attitude toward deaccessioning from the Bames collection and his refusal to permit the sale of any of the works that he owns. "Bames has no end of third-rate stuff. ' '

Annenberg's position led to wideranging speculation. A former employee of Annenberg's saw a steadfast commitment on the billionaire's part to providing the broadest public access to the Bames, a position Annenberg has taken for forty years. Others pointed out that Bames had tried to keep Annenberg from visiting the collection, and that in his book on Renoir, Bames had belittled the aesthetic achievement of that painter's 1888 Daughters ofCatulle Mendes, now a centerpiece of Annenberg's collection.

n June, I spoke on the phone with Walter Annenberg, who said Richard Glanton had sought him out last winter for his advice. He acknowledged that it was at his urging that Glanton petitioned for permission to sell works from the collection. "I find Glanton very sincere and anxious to do something wholesome for the community. I sold him on the idea," he said. "You (Continued from page 117) have to bring the Bames into the twenty-first century. The finest Matisse they have [Le Bonheur de Vivre] is jammed up on the landing of a

Continued on page 165

Barnes Storm

flight of stairs_It's criminal to do that.

That's probably the greatest Matisse that there is. You must have a new building, and that runs into a tremendous amount of money. This building wouldn't pass the building codes of today."

Annenberg stood by his description of the elegant limestone mansion in Merion as a rabbit warren. When I told him I ad-

mired the building, he balked. "I'm surprised you think the building is adequate. It reminds me of Sunset Boulevard. Have you ever seen that film? That's exactly what it is."

Annenberg said that although he had resigned as honorary chairman of the Bames art advisory committee he remained committed to reforming the foundation. "In Dr. Barnes's will, he insists it's primarily an educational institution, and accordingly I've recommended to Glanton that there be a Bames school of

fine arts." Asked if that could work in conjunction with Lincoln University, he replied, "Perhaps, or with any other university." As for continuing the foundation's courses inspired by the teachings of Bames, John Dewey, and Violette de Mazia, Annenberg scoffed. "That doesn't amount to a hill of beans. This has got to be done on a quality basis. In order to have a proper school, you need classrooms, and you need a small auditorium."

Annenberg doubted that the sale of fifteen paintings would be much of a loss to the Barnes collection. "What do you think about the fifty or sixty Renoirs? Do you think that they ought to be exhibited with the really quality Renoirs?'' he asked. When I told him that the rich selection of Renoirs at the Barnes provides a visitor with a unique opportunity to see the whole range of the artist's work, Annenberg interrupted. "Whole range? Why, half of those were done by Renoir's students." "Are you saying that half of those are fakes?" I asked him. "Not fakes," Annenberg explained. "They were done by students of Renoir." "Are you sure about that?" I inquired, remembering that Renoir used an assistant only when doing sculpture. "Well, that's my information," he said. "Anyway, some of the Renoirs that are there are ludicrous. Outsized, fat women—they're almost... ludicrous. ' '

I asked Annenberg if he had considered doing what benefactors have always done: simply writing a check to end the Barnes's financial woes forever. "Why don't you do that?" he asked. "I'm under siege philanthropically, not only from museums but from colleges, universities—there's not a charity that isn't after me for money. Every time I do anything, I get publicity on it, and that triggers another fifty communications begging for money."

Annenberg agreed that the riches of the Barnes Foundation were extraordinary. "I've never seen a greater collection of Cezannes or Matisses anywhere," he said, "including the property of the Louvre." He also admitted that fund-raising might not have to begin by selling art. "Now, it may well be that bicycling the collection around the world might be a better way of starting off seeking funds. I don't know. That's an idea that I have not mentioned to Mr. Glanton."

Throughout the spring, Glanton's plans seemed all the more mysterious because they were shrouded in a Bamesian silence. Just as the staff of the foundation had refused for decades to talk to biographers, art critics, and state investigators about Dr. Barnes, this year officials of Lincoln University repeatedly failed to respond to inquiries regarding Lincoln's plans for the Barnes. Glanton himself, when questioned about his "master plan," said he had plenty of supporters, including Julius Rosenwald II, whose father was a major art collector. "There are plenty of people," he said. "They're just not loudmouths."

Though members of the art advisory committee kept their misgivings about Glanton's proposals to themselves, outside individuals did not. Richard Wattenmaker, director of the Archives of American Art and a Barnes alumnus, was particularly concerned to see the foundation run by someone who had never taken a course there and who, he felt, misunderstood Barnes's wishes on everything from the arrangement of paintings to a ban on social events in the galleries. This spring, Glanton helped to organize fund-raising tours of the Barnes for his children's private school and for the Union League of Philadelphia, to which he belongs.

More than half of the approximately two hundred students enrolled in the Barnes Foundation's art-appreciation courses rose up against the Lincoln-appointed board of trustees. On the rare occasions when they succeeded in speaking to Glanton, they were invariably rebuffed. Soon after the petition was made public, a concerned student told Glanton that he intended to hire a lawyer to try to stop the sale of paintings. " I know you don't have as much money as Walter Annenberg," Glanton told him.

In May, Dolores Lombardi, a third-year student who teaches at a nearby prep school, arrived at the foundation at noon and was told she would have to wait an hour to get in. Lombardi objected, explaining that she was preparing a talk she was to give that afternoon on Renoir's Caryatids. She was informed that if she went in she would be interrupting something important. She could come back at one o'clock, the gallery attendant said. She returned at 1:15 with a fellow student, Nick Tinari, and the guard told them it would be another half-hour.

Since their class was to begin at 1:30, they sat down outside the main entrance. After a while, two people Lombardi had seen sitting in the galleries emerged, followed five or ten minutes later by Walter Annenberg with his wife and his niece, Cynthia Hazen Polsky, both of whom are trustees of the Metropolitan Museum. Tinari took snapshots of the billionaire, and asked him the nature of his visit. "I am just a guest," Annenberg replied, and drove off in his limousine.

Then Glanton appeared. He was tense and angry. "I'm Richard Glanton," he said, and asked Tinari his name. He told Tinari he didn't want him questioning his guests and added that he wanted to be nice, but if this happened again he'd have Tinari thrown out. "If you behave, you will be treated well," said Glanton solemnly. "If not, I will be unforgiving."

"Barnes specifically banned special

privileges, and I consider Glanton's inviting Annenberg a special privilege," said Tinari. "I don't see how a man who said the collection should be sold and broken up could be serving the purposes of the foundation as Dr. Barnes intended."

After that incident, guards at the entrance to the Barnes property were provided with a picture of Tinari and told to keep an eye on this "security risk." Meanwhile, Glanton canceled or put off meetings requested by students, and in June he dismissed a member of the Barnes faculty who was opposed to the sale of paintings.

For many students like Tinari, the classes that Barnes instituted are still sacrosanct. Texts by Barnes and de Mazia are still taught, if less militantly. Educational programs are still administered from Barnes's old office in his house, connected to the galleries by a secondfloor bridge. In 1951, this office passed from Barnes to Violette de Mazia. It is now occupied by Esther Van Sant, a Barnes alumna in her seventies.

Sitting in front of Glackens's 1916 Armenian Girl, Esther Van Sant explained that, besides running the educational programs, she is a co-trustee of the Violette de Mazia Trust. Van Sant determines how the income from this $8.5 million fund is used to further the educational ends of the Barnes Foundation. "Miss de Mazia asked me about thirty years ago if I would be the executor of her estate. I am co-trustee for life, and I pick the person who succeeds me."

The trust, which stems from the auction of the paintings, drawings, and art objects found in de Mazia's possession after her death, has kept the Barnes Foundation functioning. Last year, the trust spent $150,000 to fix the roof, $85,000 to improve security, and $30,000 for conservation—all projects for which Glanton was saying he needed funds. Until the foundation finds other sources of money, the $400,000 or so that comes in every year is crucial.

The very isolation of the Barnes from modem museum practice has meant that its treasures have never been subjected to scientific conservation. In some cases, this benign neglect has been just as well. Conservators who visit the collection marvel at the pristine condition of many of the paintings. In other cases, money is needed to stop deterioration that has been going on for decades. Works on paper, for instance, are in delicate condition. Hitherto, the only available funds for preservation have come from the de Mazia Trust. "There's Miss de Mazia's picture on the wall," she said, pointing across the room. "That nude?" I asked.

"No, not the nude, that's a Pascin. The one near Dr. Barnes," she said, indicating a photograph of a studious-looking woman with glasses and curly dark hair. "A genius," she intoned. "The most brilliant mind one will ever come across in one's lifetime. Now, let's go in and look at the collection." She grabbed her keys and walked to a door across the room. "We'll take the bridge."

The door opened onto a hallway. At the end was another door. We went up a short stairway into a room of drawings and watercolors by Demuth, Glackens, and Pascin. Several unfaded spots on the walls indicated absent works. "Wherever you see spaces, those paintings are off the wall for the teachers," Van Sant explained. "I'll show you a setup."

We walked past a series of Douanier Rousseaus into a gallery where a small, smiling man was lining up paintings on easels and benches. Harry Sefarbi, a painter and teacher at the Barnes Foundation, was preparing a class on de Chirico.

"All these pictures have been moved for the class," Sefarbi explained. Among them was a doodle of an ogre's head by no less than Violette de Mazia. "Dada is really a form of doodling," Sefarbi said, "and that happens to be a doodle."

"Dr. Barnes took it out of Miss de Mazia's wastepaper basket," Van Sant piped in.

"De Chirico is associated with Surrealism, but largely they used his techniques," said Sefarbi, launching into a typical application of "the Barnes approach." "I don't think he believed in all this unconscious business, although I don't know that. But here we talk about the paintings. I only try to talk about what the paintings say. Meyer Schapiro wrote an article on Cezanne saying C6zanne painted apples because he was afraid of women. But all men are afraid of women. They don't all paint apples, either.

One of the strongest opponents to selling works from the Barnes was Lois G. Forer, a former deputy attorney general of the commonwealth of Pennsylvania and a retired judge. Ironically, it was Forer, in the late 1950s, who initiated a taxpayers' suit to open the collection to the public. An earlier suit, brought by Walter Annenberg and The Philadelphia Inquirer, had been dismissed by a judge for lack of standing, so it was thanks largely to Forer's perseverance that in 1960 the Barnes finally agreed to open its

collection to the public two days a week.

In her apartment overlooking the Philadelphia Museum of Art, this trim, vital woman in her seventies talked about the Barnes the way Norman Schwarzkopf talked about the Iraqi army. When she fought to open the collection in the late 1950s, Forer aggressively cross-examined Violette (real name: Yetta) de Mazia. It emerged that the "education director" had never studied art in any of the celebrated European universities she had claimed she attended. More to the point, Forer discovered that, although no inventory had been said to exist, one had actually been compiled on index cards by one of the former Argyrol employees whom Barnes had brought into the foundation. Forer compared the discovery to that of Nixon's Watergate tapes: "Nobody knew there were any tapes until somebody just blurted it out."

Forer told me that she believed the secretive foundation was probably hiding much more information, and that she had urged the attorney general of Pennsylvania to subpoena all the trustees. Forer said she was hoping for a rigorous scrutiny of the foundation's five board members, none of whom has an art background, as well as Lincoln University's reasons for making those appointments and a painstaking dissection of its finances. Forer said she had also called for an investigation into what fund-raising efforts, if any, had been made before Glanton and the board opted for de-accessioning.

Besides mobilizing Philadelphia, the Barnes student body, and the art world against his gambit, Richard Glanton had managed to propose de-accessioning just at the moment when the art market was tumbling into what experts have called the worst recession since the mid-1920s.

"If they were to be given permission to take the ill-advised step of selling anything at all," said Richard Feigen in May, after the season's major evening sale of Impressionist and modem art at Sotheby's had ended dismally, "and if one were to go through that collection and do as little damage as possible, the things they would have to focus on would have to be things that have very seriously deteriorated in this market, perhaps to the extent of 40 percent to 50 percent. As for the market in American paintings, if it's not dead, it's very, very sick."

Until recently, selling Renoirs to eager Japanese buyers seemed a perfect way to make millions of dollars, but after a great many art purchases by Japanese were implicated in an array of money-laundering

and tax-evasion schemes, the Japanese "collectors" appeared to have vanished from the art market, and, according to Michael Findlay of Christie's, it was unpredictable when they would be back. Besides, according to Washington art dealer Ann Nitze, who has lived and worked in Japan, "there are more French paintings in Japan now than there are in Paris."

Even if the Barnes had been in a position to brave the current East Asian Renoir glut and "cash in" its Renoirs, those paintings had in a sense been "burned" by Walter Annenberg. A source close to the Barnes board, who asked not to be identified, wondered how the foundation could possibly justify asking high prices at auction for works of art that Annenberg had scornfully branded as "dogs." "He's undermining our ability to raise money by selling paintings by saying we have secondand third-rate stuff. The more he talks, the more he makes it hard for us not to sell significant works. In private, Annenberg told us, 'Go ahead, sell the stuff. It's not very good. ' But when he says it in public, he's hurting the very strategy we might have wanted to pursue."

Of course, if Glanton and the Barnes board were to obtain permission to sell whatever paintings they chose, the availability of masterpieces from this legendary source would no doubt rouse the art market from its current doldrums. A former auction-house expert put it bluntly: "How much is Seurat's Les Poseuses worth? If a not-terribly-good Blue Period Picasso goes for $50 million, what is this masterpiece worth—$200 million, $300 million?"

While some in the art world seemed poised for a windfall, Tom Freudenheim saw a dark threat: if the court were to set aside this ironclad will, what assurance was there that the courts would not overturn other collectors' testamentary stipulations? All museums have to maintain their pipes and air-conditioning systems, Freudenheim said, but if they can sell paintings to do it, the public will get the impression that no donations are necessary.

The combination of a crumbling art market and a rising public outcry against selling works of art to make building repairs had its effect. On June 21, the Barnes board issued the following press release:

The Board of Trustees of the Barnes Foundation today announced its decision to delete from its petition before the Orphans' Court the request to be allowed to raise endowment funds by selling one or more paintings.

The Board's decision reflects its view that the mounting adverse publicity surrounding this request is prejudicial to its case, and distorts and undermines the sound and reasonable basis on which it rests.

The Board will go forward with the other requests before the Court. It will also explore alternative means of raising the revenues necessary to carry out its mission.

Board members will have no further comment on this decision or on the petition before the Court.

CONTACT: RICHARD H. GLANTON

The coup had failed, or had it? Certainly, echoes of the commotion it had created kept resonating.

A source close to the Barnes said, "I thought it was very plausible that the attorney general was going to take an adverse position, and I thought it was a very realistic possibility that we would lose if we made this request. If I had been the judge, and I applied what I see to be the legal standard, it would have been very difficult for me to grant the authority to deaccession. ... Not only is Lincoln in a po-

sition to be the beneficiary of the Barnes reputation, Lincoln is also in a position to be the victim of the Barnes reputation. I think we were victimizing Lincoln as well as our own institution in all this."

Walter Annenberg returned to his earlier suggestion: ''I think they may use techniques like exhibiting their great art around the world, and big museums will be glad to pay a very sizable fee for exhibiting their art. At least, that's what I would do."

By the time Glanton's announcement was made, a body of Barnes students had hired a lawyer to fight the petition. One student said that the board's deleting the request to sell paintings from the petition didn't make him any less skeptical about Glanton's leadership: ''I don't trust him. He's a get-things-done guy. All the other ways of raising money are slow. I think he wants to make a big impression now, and then go off to whatever his next endeavor would be. It's obviously not anything to do with the art world."

Lois Forer wanted to know, ''What kind of judgment are they exercising?

First they say, We've got to sell these pictures because this place is falling apart, it's a disaster area. And then when the pressure is on, all of a sudden they don't need to sell the pictures. I think it's time to have some kind of accounting. The question is, are the trustees going to be faithful to the trust and preserve this collection of art, or is it going to be subverted for the use of another institution—no matter how worthy that institution is?"

Richard Glanton, reached by phone, impatiently confirmed that he had still not attended a single Barnes course. Then he hung up. The "alternative means of raising the revenues" mentioned in the announcement remain a mystery, as does the board's "mission."

On one issue all parties agreed, that the Barnes's financial woes are not over. In the meantime, the security of the place has probably been severely compromised. With all the attention that has been focused on the billions of dollars' worth of art in this allegedly dilapidated institution, every thief in the world must by now be aware of the incomparable treasures it contains.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now