Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

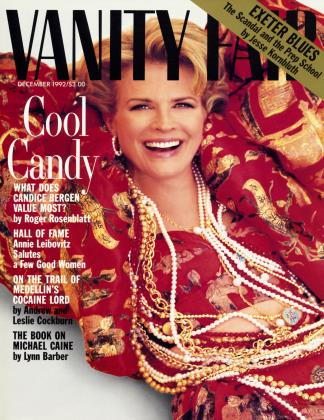

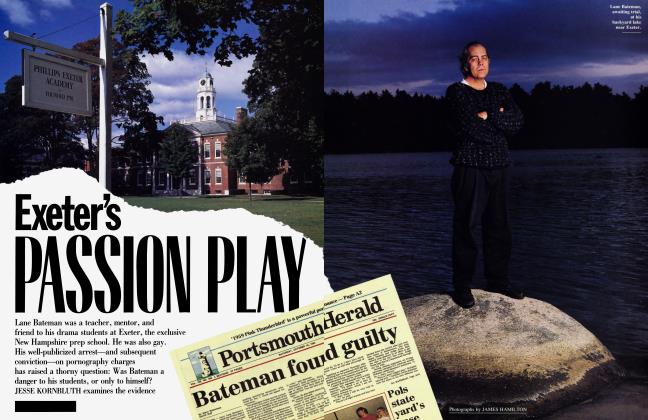

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowKeith Richards will admit to all the worst things you've ever heard about him. But both the bad-boy rep and the occasional reports of his (sort of) cleaned-up act miss the point: that all he's really after, with and without the Stones, is something honest and simple and pure. BRYAN APPLEYARD hangs with rock's main offender

December 1992 Bryan AppleyardKeith Richards will admit to all the worst things you've ever heard about him. But both the bad-boy rep and the occasional reports of his (sort of) cleaned-up act miss the point: that all he's really after, with and without the Stones, is something honest and simple and pure. BRYAN APPLEYARD hangs with rock's main offender

December 1992 Bryan AppleyardIn the dark, doped days of the early 1970s, Keith Richards carried a Smith & Wesson .38 to make his riskier scores in New York. The trick was, when things got heavy, to shoot out the lights and run. "Yeah, there was a time the dope scene was pretty rugged,'' he recalls, "and, yeah, I got used to getting shot at. You'd be visiting somebody and there'd be his dealer, who'd arrive demanding his money, and you're just sitting there.

He breaks into a nostalgic laugh made wheezy by his voracious consumption of Marlboro reds, all lit by one of his trademarks, a brass Zippo.

"... And when scoring I packed a piece to shoot the lights out and go. They'd wait downstairs to rob you of your stuff. They had a two-way street going—you'd go up and buy it and they'd take it back. It was only a couple of times; I tried to avoid doing it that way. Throughout 10 years you get into a couple of weird situations with that stuff, and that was when the drug thing was becoming really bitter. I've done chandeliers, just to get out. Just go down blazing."

These days the golden glow of universal fame and leather-jacket credibility has made him one of the safest men on the streets of New York. He is a city institution, as much a part of the scene as yellow cabs or graffiti. Even the muggers feel affectionate toward the legendary guitar man.

"Oh yeah, I've had a couple of them. Once—it was just after Theodora [his seven-year-old daughter] was born—I was walking from New York Hospital and decided to stroll home, because I felt like it. It was night and there was a railway arch and I see these two guys cross over and start walking towards me. I thought, Ah, here we go, let's see the size of them first. They pull a knife out and then they walk under the light and they say, 'Oh, sorry, Keith, didn't know it was you. On your way, son.' ... I do it [walk down the streets] all the time, which is usually fun—'Yo, Keith!' This town's funny for that. I could be mayor. Cops give me lifts when it's raining. It's great."

Keith Richards, it is always said, is rock 'n' roll. The tunnel eyes, the shocked hair, the hollow cheeks, the" lean, wasted frame, and the very tight and very loose Gypsyish clothes have become the music's most copied visual incarnation. Here's a man—the "world's most elegantly wasted"—who has flushed the entire, hard on-the-road mythology through his bloodstream. Yet still he rises, undead, to take the stage and deliver rock's most recognizable sound: a tough, weather-beaten kerchang ker-ker-ker-CHAAANG that sets scalps prickling and bodies moving. It's only rock 'n' roll, but who believes that when Keith's on song?

"I do like a good girl to come home to, if I have a home."

Knowing all this, you expect to meet the myth and the image—a sick crow of a man, haunted by the abyss and forever walking on the wild side. But what you see onstage is emphatically not what you get in life. As I enter the vaguely Moroccan living room of his cavernous Manhattan apartment he leaps to his feet, smiling warmly with an outstretched hand. The voice is croaky, a touch slurred, and very English but for the constant interpolations of "man" and "like." I came expecting the Prince of Darkness and I meet a bloke who could be bending my ear in an East End pub.

He laughs when I point this out.

"Yeah, I know. I can be the guy onstage anytime I want. Actually, I'm trying to get away from that guy. I would like to stay in touch with him.

He was dealing with a lot of self-created problems. . . . But I'm a very placid, nice guy—most people will tell you that. It's mainly to placate this other creature that I work."

There's no need to gossip about Keith; all the worst things have been said and most of them have happened. And, anyway, you can ask him. He has no time for evasions and poses. The only question which makes him edgy is about the color of his hair. I ask if he dyes it to preserve the dark-brown electric-shock look. He reluctantly admits he does: it's really gray down the sides and, after all, he's 49 in December and time ravages even a Rolling Stone. The unhidden signs are the maps of fine lines beneath each eye and the deep, oblique creases down his cheeks.

In the brighter, less dopey days of the 90s there are distinct indications that the Prince of Darkness is settling down. On December 18, 1983, on his 40th birthday, he married Patti Hansen, a 27 year-old model. With their two young daughters, apartments in New York and Paris, houses in Connecticut, England, and Jamaica, there is now a lot of ballast to slow the old rocker down. In New York he even has his father living with him, though his mother has stayed in his original hometown of Dartford.

With two children in their 20s from his long relationship with Anita Pallenberg, Keith had no plans for a second family. "When Patti and I got married she said she couldn't have babies. I said, Fine, I'll marry you. Within six months: 'Guess what, I'm pregnant!' " But the Richards-family idyll is not entirely out of character for Keith. Through all the famous debauches, his temperament was always essentially monogamous. "Yeah, if I'm on the road it's 'Hello-good-bye' basically. But, yeah, I do like a good girl to come home to, if I have a home. ... We're a great couple, me and Patti. We sorta complement each other.... You gotta have a good girl."

The memory of his second son, Tara Jo Jo Gunne, suddenly stops the flow of Keith s conversation.

The home in a heavily wooded section of Connecticut is the real family center. In a houseful of women, the improbable country squire indulges in the novelty of rural family life and homebuilding. He speaks with startling enthusiasm about pollinating the flowers on his lemon tree with a sable brush: "Yeah, man, I screw the little fuckers." In this pastoral retreat, he likes to sleep through the mornings, cook shepherd's pie, and read history books— he's halfway through one on the origins of the First World War. "Well, man, history," he explains, "you're doomed to repeat it otherwise. There's continuity and there's foolishness."

Stones history denies him access to his English home, Redlands, in Sussex. "I love the house so much," he says. "I've rented it out for the last 10 years, usually to executives and their families—Australians, Americans, Germans. I can't set foot on the property. Tax. I can go to England, but I can't set foot on my own property. Lots of things about England I never understood."

Ironically, the Prince of Darkness now looks like one of the most stable of the Rolling Stones. Mick's longtime relationship with Texan model Jerry Hall recently ran aground over Italian model Carla Bruni. "I think it will be a real shame if Mick and Jerry do split up," says Keith. "I hope the man comes to his senses. He should stop that now—you know, the old black-book bit. Kicking 50, it's a bit much, a bit manic."

Over the years Keith has become an expert on the intricacies of the Rolling Stones Girlfriend Phenomenon, from the dumb groupie to the smart cookie. He prefers the latter, even Jerry Hall. Gossip suggested he was supposed to dislike her intensely, but he denies it. "That's not true at all. Jerry and I joust. But I have a great admiration for girls who take that position. I think she's great, she's got a lovely Texas accent, and she can pull that naive bit, but she's a smart girl."

And what about Bill Wyman and the overnight failure of his marriage to child bride Mandy Smith?

"Well, there you go, a classic example," says Keith. "Mandy? Never saw that girl after the wedding. She just never turned up. We were working, admittedly, on the road, but for two years not once did she. . .well, that was it. I saw it as a disaster and it happened. But I didn't think it would be quite so hello good-bye."

Keith's oldest family, the Rolling Stones, has survived all the other relationships—though only after a five-year crisis that began in 1985. With a historian's perspective, he refers to it as "World War III." This was the acrimony that finally surfaced between him and his rock wife, Mick. They conducted a noisy domestic squabble in the columns of the British tabloids.

"Probably the whole thing happened because the frustration of just being in the Stones was wearing us down, ' ' says Keith, who now speaks about the spat with some amusement. "Working frantically for a year, a year and a half, maybe two years, then nothing for two years, continual stopping and starting. ... I was aware of it before he was.

. . . I forced Mick to break the thing. In the long run it's probably better that it happened there and then, and the proof of that is that we got back together."

The crisis had deepened when it became clear that Jagger was determined to pursue a solo career at the same time he was working with the Stones. Keith, who had always been the most devoted to the cause of the band, viewed this as an act of treason. In revenge, he signed his own solo deal with Virgin Records.

The result was a band he christened the X-Pensive Winos and an album called Talk Is Cheap.

Though the album didn't sell much better than either of Jagger's two solo efforts (and none of them did anywhere near as well as an average Stones album), Keith's picked up the best reviews. Did the revenge taste sweet? "I suppose there was a sort of little inner demon saying, 'Told you so,' " he admits. "Just because we were at each other's throats all the time. 'You still can't do without me'—bit of that sort of thing. But at the same time he didn't fall flat on his face and he does get up pretty quick anyway."

The reunion with Jagger finally took place in Barbados in 1989. As he was leaving home, Keith told Patti he would be gone either two days or two weeks— depending on how the encounter went. Keith and Mick screamed at each other for a while, then fell to laughing at the names they had traded in the tabloids. (Mick accused Keith of trying to take over the band; Keith called Mick a "bitch.") He stayed two weeks, and a month later all the Stones gathered in Barbados to prepare Steel Wheels and the blockbuster world tour.

The Stones are rolling smoothly again —a new album is scheduled for next year—and Keith speaks excitedly of his premonition that they are about to enter another "golden period," but he also remains committed to his solo career: the X-Pensive Winos have just released their second studio album, Main Offender.

It's a laid-back piece of work, looser and more relaxed than the music of the Stones. The Winos cruise rather than rock, with Keith's voice rolling alongside. Some of the old whiskey rasp is gone. He sounds almost fragile and vulnerable, meditative and drifting rather than hard-rocking. Keith is the Main Offender of the title, of course. "I've spent too long saying, 'Not guilty, Your Honor,' " he says with a smile. He originally wanted to call the album Blame Hound—"You know, the d6g that lies under the table and gets kicked when anybody farts."

Keith wants to take his new songs on tour, and he plans more X-Pensive Winos albums, but it's impossible not to miss the passion of his lifelong commitment to Charlie Watts, Ron Wood, Bill Wyman, and, yes, even Mick Jagger. "It's kind of like an adventure, the Stones," says Keith. "You can't give up now. Once you're in, you take it to the end."

Keith—or "Keef," as Cockney pronunciation demands—Richards' place in rock 'n' roll history is now secure. Recently, a fat, heavily researched, though unofficial, biography, Keith Richards: The Biography, by Victor Bockris, reverently traced the pattern of his life as if he were a statesman or a saint. Keith is simply, according to the book jacket, "one of the most important guitar players and greatest songwriters in the history of rock and roll."

Keith, who says he hasn't read the biography, seems uncomfortable with another immortalization in print, another long, detailed recapitulation of all the sex, drugs, and rock V roll. But the point that he cannot avoid is that his life is not just another tale of a debauched rocker—it is the standard by which all such tales are measured. What has made his life so enviable and exemplary is that unlike so many others— Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Brian Jones, Mama Cass, Keith Moon, John Bonham—Keith has walked through rock's valley of death and survived relatively unscathed. In fact, what didn't kill him seemed to make him stronger. He inspired admirers to think the human frame could endure years of cocaine, speed, heroin, Jack Daniel's, marathon insomnia, and total blood transfusions—when in fact only his could.

Born a week before Christmas 1943 into a working-class neighborhood in Dartford, on the Thames east of London, Keith was hardened in the grim austerity of postwar England. "Until 1954, we got beat up pretty bad," he remembers. "First, Hitler puts a bomb on my bed and then no sweets." (According to Bockris this is a routine Keith exaggeration: near the end of the war, a nearby explosion hurled a brick through his cot, though he wasn't there at the time.) "In England after 1945, everything was just drifting, everything was just postwar, you know. Until the middle 50s, everything was just the war. 'Why can't we. . .?' 'The war.' The war went on for years. They said it finished in '45. About '56 for me. . . . The feeling of how are we going to get out of this hole? We've won two wars and we're dying."

He grew up in a rough part of town and learned to look after himself. "I've never thought of myself as brave," he says. "When I'm confronted with a situation, there seems to be only one thing to do. And I think maybe that's because I've never been a big guy. Because of my birthday, which is in December, I would always, through the weirdness of the English educational system, be like virtually nearly a year younger than the class I was in. When you are like six, seven, eight, or nine, a year is a long time, so I was always the little guy.

"I had to learn pretty much to handle myself, mostly with repartee. If there was no way out I would just go for the jugular. That's always been with me. And you've only got to do that a couple of times and everybody knows. I don't enjoy it, but there's something in me—when the situation demands it I just go."

What's the worst damage he's ever inflicted? "Oh, lacerations, broken ribs. I've taken some beatings, too."

He was a dud schoolboy who had managed to just scrape through by exploiting a talent for drawing. He was looking forward without enthusiasm to a possible career as a graphic designer when rock 'n' roll hit him "like a thunderbolt." Leadbelly, Muddy Waters, Bill Haley, Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly. In 1956, he plugged into that strange historical mix of a free, dreaming America and a poor, drab, frustrated England that gave birth to modern rock. "English kids' dreams could come true," muses Keith. "You could go and see Muddy Waters. You could actually do that, people like that actually playing around the comer. . . . Then you're getting paid and chicks are throwing themselves at you. You can't complain at 18 or 19 about that—things had definitely taken an upturn in my life."

Thanks to a shrewd grandfather named Gus Dupree, who played jazz saxophone, fiddle, and guitar—and who Keith has called "the funkiest old coot you could ever meet"—Keith had already grown obsessed with the shape and sound of the guitar, and especially the way "it pulls the chicks." He taught himself the instrument and met up with an old primaryschool friend, Mick Jagger. After scuffling around Soho and Chelsea for a while, the Stones were bom. The idea was that they were a rough, dangerous, antifashion band, an antidote to the saccharine mop-top style of the early Beatles. For Keith it was all idealism, a crusade to bring the authenticity of the American bluesmen to the postwar English generation.

But it soon got wildly out of hand. One minute Keith was the quiet boy at parties, the next he was one of the most sexually desirable men on earth. "Like I slid into it very easily," he remembers with a nostalgic smile. "This is for me, I thought, playing and doing what I want to do and getting paid for it. Traveling and seeing the world. The furthest I'd thought I would get abroad was Southend, staring at Calais. And then the whole world is opening up and travel does 'broaden the mind,' especially in a rock 'n' roll band."

Any regrets along the way?

"The answer is no. It's all right having fantasies and dreams come true. Trouble is, when they do, they're no longer true, they're just real."

By the end of the 60s the Stones could call themselves "the Greatest Rock 'n' Roll Band in the World" and few argued. They were the royal family of street funk. But there was a two-way pull embodied in the personalities of Mick and Keith. Keith was the symbol of dark hard-rock authenticity, while Mick veered toward pop, the high life, the gossip columns. The pressure was real and there was soon a casualty: Brian Jones died just weeks after Mick and Keith had told him he was too wrecked to go on the road. All Jones had cared about was being a pop star. He had neither the bourgeois stability of Mick nor the survival instinct of Keith.

In the early 70s the Stones were forced into tax exile from England and became a multinational operation. The band dispersed to overseas homes, reuniting only for records and tours, no longer able to indulge in casual jamming. "The hardest part was when the Stones had to leave England," says Keith. "Up until then it was 10 minutes to get in touch—'Come over, I've got an idea'—and, of course, a band has to be a tight-knit unit. When they couldn't put us in jail, they put the economic sanctions on us instead—'Oh, we've blown that one, let's try 'em with the big screw: eight million quid.' What it meant was that either we coughed up or left. It was '71, after endless raids and busts. ... I just wanted to play the guitar, you know, and then I was hassling with the British government. Wow! I'm the bad guy, I'm the Main Offender."

By then Keith was a father. His son Marlon was bom in 1969 to Anita Pallenberg and his daughter Dandelion in 1972. Eventually she went back to England, where she was raised by Keith's mother in Dartford. She renamed herself Angela and now works in a horse stable. Marlon, however, was brought up on Rolling Stones tours. It was a hair-raising upbringing, but he survived life with Dad and his strange "uncles." Marlon is now a laid-back, faintly raucous student at New York's Parsons School of Design, and lives in Keith's huge Lower East Side apartment. His strongest stimulants, insists Keith, are cigarettes and champagne. "I'm the supreme example of what not to do for my kids," Keith admits. "Marlon, he knows more about the dope business than me and he doesn't take anything. He has great hangovers.

"The best thing about having kids is that through them I could remember that bit I couldn't remember on my own. I remember feeling like that—eeeeah! Frustration, not being able to say why you are pissed off. They give you back that bit you don't remember."

The memory of his second son, Tara Jo Jo Gunne, suddenly stops the matey flow of Keith's conversation and he crouches forward on the sofa. The baby was born March 26, 1976. The next month the Stones released Black and Blue and went on tour. On June 6, Tara choked to death in his crib. The Stones were in Paris. At Keith's insistence they did not cancel the concert.

I ask if he felt any guilt.

"Yeah, not being there. Little chap in his cot—'Daddy'll be back in a couple of months, he's going on the road, soon you'll find out what it's all about.'. . . Not a lot to say about that."

Later, however, he comes back to the subject. "Just on a reasoning level it brings home to you that nobody gets a guarantee in this life. You don't necessarily get three score years or whatever it is. It seems to me there's some people who want to believe it's your right. But it's not like that, is it? You can be a day old, you can be two months old, as Tara was. It's a fragile thing, life, and first you've got to get a hold on it. When babies die it all seems so pointless."

He falls silent, sighs, and then picks the memory up again. "All of that to be bom for eight weeks. Well, eight weeks is a lifetime. You actually block it out. He comes to my mind in the weirdest places. I just remember his chuckling.

Tragedy is an integral part of the Keith Richards legend. Brian Jones and Tara were followed by his close friend countryrock singer Gram Parsons—"a pure soul" —and Ian Stewart, the closest and oldest friend of the band. And there was, of course, the shadowy gunman the Hell's Angels killed while the Stones played "Sympathy for the Devil" onstage at Altamont. But only Tara makes him pause. He speaks fluently about those other deaths with a resigned acceptance of the price exacted by the life of the road. In fact, he thinks the body count in his life is no higher than in others'; it's just that every death in his vicinity makes the headlines and feeds the image of the wasted rocker on a death trip.

The miracle, of course, is that Keith himself lived. The decade-long debauch that climaxed with the Toronto heroin bust in 1977 should have killed him several times over. But somehow death passed him by, and very slowly he started to pull back from the edge. One of the conditions of the Toronto court's decision was that he undergo psychoanalysis. An analyst thought Keith was well enough to serve him vodka and ask little more than where he had his clothes made. One of the strange continuities in his life is the way doctors of all varieties have never seemed to be able to find anything wrong with him. Most just lamely suggest that it might not be a good idea to treat his body as a laboratory.

Keith now says he's clean of drugs, though he still drinks. He denies claims in the Bockris biography that he is effectively an alcoholic, pointing out that he gave it up for a month last year. Even heroin is not that hard to kick, he says—people can do it in three days. (He admits, however, that he shouldn't say this too loudly, as it might encourage new users.) Indeed, he insists he can give up everything except for smoking.

Old superstar rockers can settle down only so far. There is no easy trail down from the highest peak of global celebrity. As Keith puts it, with the precision of a well-rehearsed insight, "You can fall down, but you can't climb down." Which means that nothing can ever be quite normal; people will always want to attach themselves to your fame. "The public imbue us with the mythical talismans and stuff—that's a bit of that primal, tribal thing," says Keith. "You get decorated like a king. 'Oh, he's in touch with God and the divine right ' "

But the side effects of fame are not always benign. At the far end of the public's impulse to connect with these people is the threat of obsessives like Mark David Chapman, John Lennon's killer. Keith, who says he was on Chapman's hit list, now lives with the constant necessity of taking precautions, noting regular phone calls, letters, or people trying to see him. "If you live somewhere for a bit," he says, "certain nuts tend to drift around, you get phone calls. So once or twice I've called a private eye, and I just had the guy check up on someone. The classic example was this guy who was a nut and he kept coming round. We later found out that he'd had a car crash. He'd actually broken his neck but was still alive. So we got in touch with his parents and we put him in a clinic for a bit and straightened him out. You try and pre-empt it if there's obvious signs of it going around. You try and put it together so you can help them out before they do something dumb."

The constant proximity of death from outside or within has not exactly driven Keith into the arms of God. "In extreme situations, I've often thought, There's only One Guy who can get me out of this. But the time when I was really touched with any religious impulse was probably with the Rastafarians in Jamaica because at that time—it was for a very few years [in the 70s]—it was very pure and structured and it worked. It was a very handto-mouth existence and pretty squalid, and they managed to get a pride and a community thing and emotion going. The actual religion was dumb when you examined it. But what religion isn't? It was probably no weirder than any other. ' '

But even cleaned up, slowed down, at peace with himself, and protected by a private eye, Keith is not a fundamentally changed man, and that, finally, is the point. He still clings to the idealism of the first days of the Stones. He still sees an inner core of truth and authenticity in the band that is anti-fashion, anti-pop, and in a straight line of descent from the American bluesmen through Chuck Berry to the Stones.

This has made him publicly critical of the glitzy approach of rock peers like Elton John. "I've known Reg Dwight [John's real name] way back and he's a great musician and a great guy," Keith says. "In a way, I'm not knocking these guys, I'm knocking the things you get forced into. You put on a hat and a big pair of glasses and everybody loves you and you think that's great and then you're doomed to wear them forever because if you don't do that you can't do anything. Nobody wants to see you."

This austere preservation of the rock faith, Keith is convinced, has helped change the world. "Probably blue jeans and rock 'n' roll had more effect in undermining the Iron Curtain idea—that you can close off millions of people from the rest of the world—and showed it to be a sham. Forget about it. It won't be the hydrogen bombs or the missiles, it will be something quite simple." Rock 'n' roll, Keith thinks, is "probably the best work the English have done since the empire. We took it and ran with it. . . . It was one of the biggest weapons the English had and they didn't know it. Maybe the Berlin Wall would still be up without it. You can't stop music at the border. Music is one of the most powerful and insidious and subtle weapons. It can penetrate areas that no K.G.B. or C.I.A. can possibly get to. It's a beautiful armor-piercing weapon, man."

What counts, Keith emphasizes, is keeping rock pure and real. Over and over again he comes back to this, the bottom-line justification of all that he has done and been, of the elegantly wasted crow with the guitar, of the Greatest Rock 'n' Roll Band in the World, and, finally, of the Connecticut gardener with his lemon tree. "The noncontrived thing was probably the most basic and most important thing about the Stones," he says proudly. "It's not an act you're watching. For better or worse, it's what it is. . . . Touching people, yeah, and not faking. Especially in this world today there's so much acceptance of downright phonies—you're expected to be phony. I just lost patience with all of that. I can play that game, but it becomes so confused, everybody can get so confused. I kinda like a bit of clarity."

The point, Keith says, is to keep rolling, to, as he puts it, "grow up" the art of rock 'n' roll, to age with the weather-beaten dignity of his mentors, the great, hardliving bluesmen Leadbelly, Howlin' Wolf, Muddy Waters, and John Lee Hooker.

And when Keith can no longer leap about the stage? "So sit down and play," Keith shrugs. "Muddy Waters did. By then you've got to be so good at the music that you don't need to watch anybody leaping around. The music's got to do it all by itself. That's my dream." And for the day the music dies, Keith has a joke epitaph—"I told you I was sick"—but the line he really wants on his tombstone is: "He passed it on."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now