Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE GETTYS' PAINFUL LEGACY

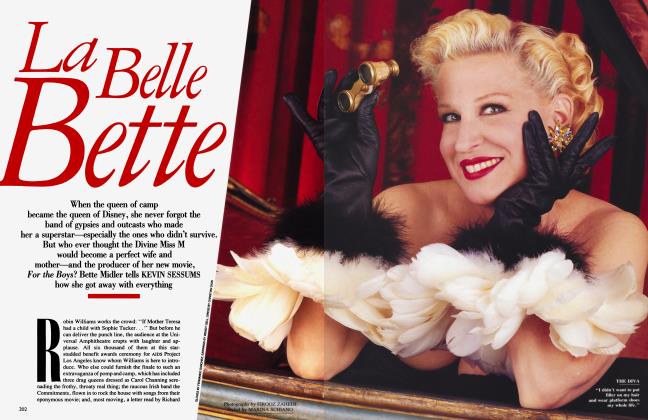

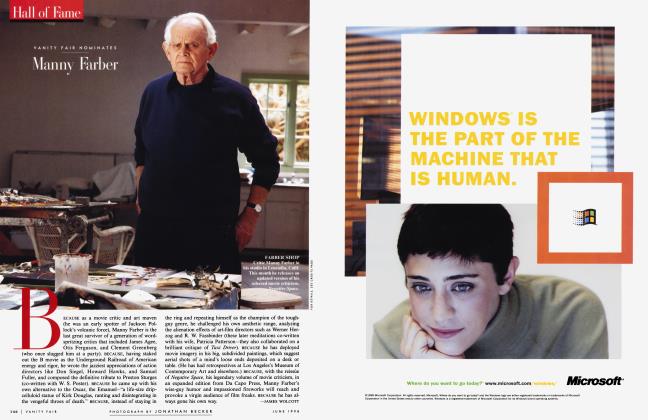

KEVIN SESSUMS

The AIDS battle of Aileen Getty, granddaughter of Jean Paul and former daughter-in-law of Elizabeth Taylor, has rocked a family already plagued by sorrow

Dispatches

There were seven of us seated at Aileen Getty's Thanksgiving table, high in the Hollywood Hills. A favorite granddaughter of the late oil financier Jean Paul Getty, Aileen is the second child of his fifty-nine-year-old son, Eugene Paul. Her father changed his name to Jean Paul Getty Jr. in 1958, and now, a heroin addict free of heroin, he is a virtual recluse in London, where he lives off the income of the billion-dollar Getty trust, which he had to battle his brother Gordon to get. Thirtytwo years old and suffering from AIDS, Aileen Getty was born into a dynasty which, at the beginning of the 1900s, became synonymous with the most American of dreams: hard-won wealth. Now, as the 1900s come to a close, the Gettys are once again serving as a paradigm for America's newest preoccupations: dysfunction and disease.

"I think with this family everything is so mixed up with money that no one can really trust anything," says Gisela Getty, the handsome German who married Aileen's older brother, Jean Paul Getty III, in 1974, when she was twenty-four and he was seventeen. One year earlier, the young heir had been kidnapped in Rome, and his abductors had cut off his right ear in a final desperate act to force his grandfather, who was busy spending millions of dollars on art back in London, to pay $850,000 in ransom. Although Gisela recently divorced J. Paul III, she had cared for him for years after he suffered a debilitating stroke at the age of twenty-five, and she remains close to the family. "There is no one black sheep in this family," she told me, having contemplated the clan since she lived with J. Paul III on the Via della Scala. "We are all black sheep."

Thanksgiving is the most familial of American occasions, but Aileen Getty was alone last November except for her invited guests. Her two children, Caleb, eight, and Andrew, seven, by her exhusband Christopher Wilding, a son of Elizabeth Taylor, were visiting their paternal grandmother, and her immediate family members were spread around the world. There was, however, one "blood relative" present, a nine-year-old boy named Dallas. Of Aileen's guests that day, five of us were homosexual, yet she, a heterosexual woman apparently infected by a blood transfusion, and the child, infected at birth, were the two people there who had AIDS.

Dallas comes from a well-heeled family himself, one that wears cowboy boots with their three-piece suits. The child's name is purposely meant to evoke southwestern geography, for his great-grandfather was once governor of Texas, yet the family considers Dallas its own black sheep and has largely ignored him. His mother died less than a year ago, after a lengthy bout with AIDS, and his father is now close to death from the disease. Before her death, Dallas's mother made one of Aileen's guests, L.A. artist Mark Lipscomb, his legal guardian. But it is Aileen, though weakened by the disease herself, who has become a substitute mother for him.

"I love Dallas," Aileen told me after dinner as she offered the child some of her extra AZT tablets, one of the few drugs which seem to stave off the progression of AIDS. "He's a special child," she said. "I think I am now the only woman left in his life. He tells me that I remind him of his mom."

Getty's own substitute mom is Elizabeth Taylor. Though the marriage to Taylor's son did not work out, Aileen has remained extremely close to the star. She refers to her natural mom by her first name, Gail, but she reserves the more loving appellation for Taylor. It was on a 1985 fund-raising trip to Paris with Taylor, who is founding national chairman for the American Foundation for AIDS Research (AmFAR), that Aileen became convinced that she had been infected with the humanimmunodeficiency virus (H.I. V.), which leads to AIDS. ''I was

sleeping in the room with Roger [Taylor's beloved late secretary], and I woke up the next morning and was all wet from a bad night sweat. . . . I was soaking. I turned to Roger that morning and said, 'Roger, you know, I got it.' I was real scared. Roger said, 'No, no, no, no, no.' But I knew it." After her diagnosis, Aileen was panicstricken over her condition, and Taylor, who had just suffered the loss of her great friend Rock Hudson to the disease, allowed her to move into her Bel-Air mansion. At that time, Aileen was so frightened that she would crawl into bed with Taylor at night, and, forming an American Pieta of fame and fortune, the world's favorite movie star would cradle one of the world's richest heiresses until they both could fall asleep.

Even though Taylor's relationship with Aileen has been a complicated one because of her son's legal battles to gain custody of Andrew and Caleb, she has remained stalwart in her support as far as the illness is concerned. Aileen, like her father, has had a history of drug abuse, though her drug of choice was cocaine, not heroin. She finally agreed to submit to scheduled urine tests, and she and Wilding now have an amicable arrangement to share the children on a weekly basis. A few months ago, however, a bit of tension arose when the supermarket tabloids printed stories regarding Aileen's AIDS fight and Taylor's purported hysteria over the health of her grandsons.

"I love Aileen," Taylor told me. ''I've always loved Aileen. I always will love Aileen. This is her story, but I feel I have to respect and protect the privacy of my grandsons. I will always be here for Aileen. I have kept this issue private and confidential and between us for years, and that's the way I would prefer it to stay."

"The worst symptom of AIDS is denial," Aileen told me at Thanksgiving to explain why she had decided to go public with her disease and talk to me. Her voice was gravelly, grave. There had recently been an outbreak of painful blisters inside her mouth, which caused her to sound like the lockjawed lady her family has always wished she could be. "AIDS is less deadly than denial, as far as I'm concerned," she insisted. "I don't think this is a disease you survive in any way, shape, or form without others. And I don't think that others—the parents and the families and the lovers and the friends—can survive the issue within themselves unless they can bond with the patient."

"There is no one black sheep in this family," Gisela Getty told me. "We are all black sheep."

"Bond" has usually been a noun in the Getty household, seldom a verb, so it is no surprise that the person with whom Aileen seems to have bonded the most is her newest acquaintance, nineyear-old Dallas. He quietly excused himself from the Thanksgiving table, and Aileen soon followed after him. She smiled when I knocked at the door of her tiny study, where she was teaching him how to fashion a fish by folding a piece of paper. The walls were plastered with snapshots and mementos. In one photo, Aileen posed with Jesse Jackson on the night of the 1988 California primary. In another, Timothy Leary motioned in mid-speech at a campus forum. Most of the photos, however, were of Andrew and Caleb. The many notes that they have written to their mother throughout her illness were also posted all over the walls, DEAR MOMMY, began one, I WISH I COULD BUY YOU A BUNNY AS A PRESENT. I LOVE YOU SO MUCH. SMOOCH SMOOCH SMOOCH.

"What's that?" I asked, pointing to a primitive drawing of two large ships taped to the wall beneath a poem by Aileen entitled "Retrovirus," which she had carefully typed for display. Each ship in the drawing contained two stick figures stowed away below.

"That's a drawing Dallas did when he spent the night with me recently," Aileen told me, and lovingly looked at the boy. The dying, like family, simply belong to each other: one ship contained Lipscomb and his longtime friend, the other held Dallas and Aileen.

"Why does yours have a helicopter over it?" I asked. "It's even got a ladder dangling down toward the two of you."

"Want to tell him, Dallas?"

Dallas shyly shook his head no. Aileen started to tell me, but erupted in a coughing seizure.

Dallas looked up from the sharp-edged fish. His childish voice was full of reason and hope. "It's there so when we have to, we can. . .you know. . .escape."

There is no escaping the destiny of the Getty dynasty. Aileen Getty's battle against AIDS is just the latest chapter in a family saga replete with tragedies so extreme that a Puccini could have scored them—or perhaps a Getty. Aileen's uncle Gordon, her father's brother, who is married to the publisher Ann Getty and lives in San Francisco, is an eccentrically accomplished composer and has been quite supportive during her AIDS fight. His suite of musical compositions based on Emily Dickinson's poems on death and desolation could indeed have served as a prelude to his niece's current plight. "I love Gordon," Aileen said, smiling at the mention of her uncle's name. "Gordon is great. . .he just stays in his room and writes music and is happy as can be. He's just a great guy and very, very different. Very different from my father. They're total opposites. Gordon is light, and my father is the dark side."

"In terms of personalities, the brothers are quite different," confirms Judge William Newsom, who serves on the California Court of Appeals. Newsom has known J. Paul junior and Gordon since childhood, and has always been the Getty-family troubleshooter. Whether working out the details of J. Paul junior's divorce from Aileen's mother, Gail, so that Paul could marry the flamboyantly beautiful Talitha Pol, who died of a heroin overdose in Italy in 1971, or dealing with the kidnapping of his godson, J. Paul III, Judge Newsom has been the person the family calls on when a "father figure" is needed. It is certainly needed now, and Newsom tells me, appropriately enough, about a business transaction involving the far-flung family members as proof of their renewed emotional health. "We're all taking a trip to South Africa. Mark Getty, Aileen's younger brother, who works for Hambro in London, and to whom Gordon is extremely close, is putting together an investment in connection with the African National Congress and the current South African government. It involves building a hotel for game-viewing guests in a pristine area of South Africa. The local tribesmen will run the hotel, run the buses, etc. It is a money-making project, but, more importantly, it carries with it a concession from the government of rights to a vast wildlife habitat of several hundred thousand acres. This ties into the family's historic involvement with environmental and conservation causes. Gordon funds the J. Paul Getty wildlife prize, and the daughters of his late brother George are big donors to conservation causes. Involved in this South African project are Gordon's own boys, led by Peter, who is the oldest—about twenty-six or so now. So that's one part of the family. Christopher Getty is also involved. He is an extremely capable young guy, about twenty-six or twentyseven, and is the oldest child of Ronald [another of J. Paul Getty's sons, who was virtually disinherited because of the demands made by his German mother during her divorce from J. Paul, but whose children have been provided for]. Christopher runs the Ronald Getty Family Trust. What I'm saying is that I see this family coming together in a lot of ways. I see the tragic parts of it being in the past. Things have really turned around."

Aileen was so frightened that she would crawl into bed with Taylor, and the world's favorite movie star would cradle one of the world's richest heiresses.

Judge Newsom returns to the most famous surviving Gettys: "Paul is more reserved; Gordon is more outgoing. Gordon is more in the world; Paul is much more private. But they both have an intense interest in, and an encyclopedic knowledge of, music. Both would go anywhere anytime to hear a great tenor sing. They do have that in common. In the worst, most acrimonious days of their lives, they could still pick up the phone and say, 'Hey! Did you hear Domingo sing in Madrid the other night? He was fabulous!' "

The acrimony stemmed from the legal battles J. Paul junior waged against Gordon when the latter was left in charge of the Sarah C. Getty Trust, the sizable remainder of their father's estate left for the family to squabble over after the old man had endowed the J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu as his real legacy to the world. (Plans were revealed last October for a second project, the $360 million Getty Center, designed by Richard Meier and slated to open in 1996 atop the Santa Monica Mountains in Brentwood, California.) Modeled after the Villa dei Papiri, which stood on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius in the first century, the J. Paul Getty Museum is tied into the billionaire's secret belief that he was the reincarnation of the culturally sophisticated Roman emperor Hadrian.

J. Paul junior used his son by Talitha Pol—Tara Gabriel Galaxy Gramophone Getty, now a dashing twenty something boy-about-London—as the litigant in the case against his brother, and was successful in dividing up the family fortune in a more equitable manner. (The fortune actually increased in value during the family's fight over it, when Texaco took over the Getty enterprises for $10 billion.) After winning his rightful share, J. Paul junior stunned the art world of Britain in the 1980s with a donation of approximately $63 million to the National Gallery. He has also set up a charitable trust for social, medical, and environmental causes.

Though Aileen is not aware of any sizable donations to AIDS charities, Judge Newsom insists that her father has given generously to medical research for an AIDS cure. She is, however, quite specific about her father's penuriousness when it comes to her more immediate medical bills. Just as he had to be sued by Gail to pay J. Paul Ill's medical bills after the young man's stroke, he also had to be urged to help pay his daughter's mounting bills, which, according to Judge Newsom, he is finally doing. "There have been a few times that I have been struck that I haven't really had the money for medicine or some kinds of treatment I haven't been able to follow through on," Aileen claims. "It has struck me as certainly very odd."

The Getty lineage has been filled with extravagant wealth and extravagant sorrow; it has by turns been greedy and generous, loving and aloof, sober and debauched. J. Paul Getty forever grieved for his youngest and favorite son, the sickly Timothy, who died in 1958 when only twelve years old, and he never recovered from the 1973 suicide of his handpicked successor, his eldest son, George, who was the namesake of Getty's own, beloved, but distant father. However, the old man needed only to look back at his heritage—post-Hadrian—to understand the Getty willpower, which enabled him to carry on, a salient family attribute that has kept his granddaughter alive.

The Gettys have been in turmoil since James Getty immigrated to America from County Londonderry, Ireland, in 1780 and bought from the heirs of William Penn the land which would become known as Gettysburg. A decade later his two cousins John and William Getty followed. William headed for Kentucky, and was never heard from again, but John became one of the first £ settlers of Allegany County, Maryland, where he married and became a prosperous farmer until his wife's death. Left with three children to raise— James, Polly, and Joseph—and bereft at the loss of his spouse, John Getty became the town drunk, thus initiating a long succession of Getty men and women who would find solace in alcohol and, later, drugs.

After their father died from a fall from a horse in 1830, the three Getty children were left penniless, but somehow managed to rise above their station, and all three made successful marriages. It was James, John's elder son, who gave the world the Getty dynasty we know today. James and his wife had three sons, each of whom went on to a successful career. The youngest, John Getty, who wanted nothing more than to be a farmer, moved to Ohio with his wife, Martha, a schoolteacher and a minister's daughter. Their first child, George Franklin Getty, was born within the year. Three more children rapidly followed, but at the age of twenty-six John died of diphtheria, leaving Martha impoverished, with four children, all under the age of six.

George Getty, even in his childhood, worked in the fields in order for his mother and his siblings to survive. Finally, an uncle sent for him and paid for his education in Ohio. At university he met Sarah Catherine McPherson Risher and married her after graduation. Within a year, she gave birth to their first child, a daughter, Gertrude Lois.

George taught for a short time, but ultimately gave in to Sarah's insistence that he study to be a lawyer, and he eventually became quite a success in Minneapolis, where he specialized in insurance and corporate law. In 1890, just as their lives seemed secure, a typhoid epidemic carried off their adored daughter. The couple seemed inconsolable until Sarah became pregnant again at the age of thirty-nine. In 1892 she gave birth to a healthy boy, Jean Paul Getty, who, by the time of his death at the age of eighty-four in 1976, had built his father's later ventures in the nascent crude-oil business into a conglomerate that caused headlines to hail him as "the richest man in the world."

'I knew him very well," Aileen says, remembering the many weekends she spent with her grandfather at his London estate when she'd return from boarding school as a girl. "He was a good guy. Actually, funny enough, he was one of the more nurturing members of the family. You don't expect that, but I have more solid memories about him as far as feelings of family and interest in family. I would spend time there at his house when I would get in trouble at my father's and I would be sent to my grandfather's. He had lions as pets in big, big, big cages, and I would play with them. Then they had babies, and I was the first one to be shown the cubs when they were bom. They were brought up to my room one at a time." She smiles at the memory, then adds, "He also had eight or ten pretty vicious dogs. Well, I mean they were really sweet, because dogs are sweet no matter what, but they bit. They were Alsatians. You know, those German dogs."

J. Paul made quite an entrance at his father's funeral, when he arrived wearing bright-yellow shoes and with Bianca Jagger on his arm.

In 1959, J. Paul Getty, whose love of Europe had been nurtured by his father on frequent trips to the Continent in the early part of the century, had chosen to settle down near a European capital after years of living out of hotel rooms. He was, after all, sixty-six years old. While residing at London's Ritz Hotel, he was invited to a dinner party by the Duke and Duchess of Sutherland at Sutton Place, their country estate in Surrey. Sutton Place—all seventy-two rooms of it— was considered England's finest example of Tudor architecture, but the duke, who was having financial difficulties, confided to Getty over dinner that he would like to sell the place. Getty's first home in New York had been a penthouse on Sutton Place, and he was immediately taken with the symmetry such a purchase would provide in his life. He bought the house and its sixty-acre park for a little less than £65,000.

Aileen's most vivid memory of her grandfather is his funeral in Mayfair. "I was fifteen or sixteen, and I cried a lot at his funeral. A lot. I was always afraid of acknowledging others' deaths too much, because I was afraid it would hurt me in such a way that perhaps I would lose control. I cry very easily. I also remember being embarrassed, I must say, because my father was late for the funeral. Very late." J. Paul junior did indeed make quite an entrance that afternoon, when he arrived wearing bright-yellow shoes and with Bianca Jagger on his arm.

Aileen's father inherited his own father's love of England, if not his business acumen. Although he cloistered himself in his home on Cheyne Walk in a drug-induced haze after the tragic death of his beloved Talitha, he has recently re-emerged to some extent from his reclusive past. "He is very intelligent, very bright, very witty, but also very much in his own world," says Gisela Getty. "I don't think he really likes to deal with family matters." Like his father before him, he has turned his attention to the creature comforts his wealth can provide. He has, for example, just finished building a library at Wormsley Hall, his estate forty miles outside London, for his collection of four thousand incunabula, the world's largest and most valuable, which includes a Magna Charta of 1215, the Paris Psalter of 1230, and the scant remaining pages of a Life of Thomas a Becket. A cricket aficionado, he not only is a major donor to the Marylebone Cricket Club but also is putting the finishing touches on the field he has had constructed at Wormsley, where he plans to hold matches to benefit his favorite charities.

Why this onetime rebel's dotty Anglophilia?

Judge Newsom: "He's read too much Trollope."

Before he could retreat into the parlored life of the ersatz English, J. Paul junior, at his father's insistence that he run a family business in Italy in the late fifties, settled his then wife, Gail, and his children, J. Paul III, Aileen, Ariadne, and Mark, in Rome. "Those were tough, tough, tough years," Aileen says of the time associated with her brother's kidnapping. "I was always a pretty serious, quiet kid. I didn't play much. I read a lot and liked to play with paper—just shuffling and touching paper. . . . We lived twenty minutes away from Siena, on top of a mountain. The closest thing to us was a little village called Orgia. We only had electricity by generator, and for hot water we had to light this gas thing. There wasn't even a telephone."

Getty's younger sister, Ariadne Getty Williams, now an architectural photographer, remembers Aileen as "actually the quietest of us all. She was the most feminine. She was very delicate. Very, very beautiful. Very girl-like. I was very tomboyish, and always with Paul and Mark. Aileen was the one that was always helping my mom in the kitchen."

Now delicate from disease, but no longer "the most feminine," Aileen somewhere in her life turned into a hoyden with a wild streak as big as her family's bank account. Indeed, pugnacious and disturbingly pretty, she bears an uncanny resemblance to the young Robert Mapplethorpe. ("The first time I saw her," recalls a good friend, "I thought she was this really cute Italian street boy.") When—and how—did such a dramatic change in her appearance and attitude take place? "She has a history of drug use, and I think all those types of things harden you," says Ariadne, who has been the most understanding of any of the family members regarding her sister's AIDS fight. "I think drugs create new realities. Especially cocaine, because it is such an insidious, strong, character-changing drug. I also think Aileen—like everybody—has had tough knocks in life, and you sort of build your walls up. Aileen has built several walls."

In her teens, Aileen was sent to London to live with her father, who was divorced from her mother. He, in turn, shipped her off to a small finishing school, Hatchlands, which was near her grandfather's estate and had an enrollment that consisted almost entirely of Iranian princesses. "It was near Guildford, in Surrey, in a beautiful Robert Adam home," she says. "I learned how to curtsy to the Queen and how to fence. Mr. and Mrs. Hargreaves were the director and his wife. He'd come down to dinner every night wearing a tuxedo, and would eat an entire cauliflower and a half a roast beef. We had nail checks three times a day. I was not ready for this school: I didn't have nails to check! The headmistress would bang on the table and scream, 'Entertain me!' Of course, no girls spoke English there but myself, so I was the one who always ended up having to carry on about something. I'd make up stories to tell the Iranian girls. . . . My father got really alarmed at the sum of money that the school cost when he got my report card and the subjects started out with contract bridge and flower arranging. Say what? But they did introduce us to the boys in the nearby military school. We weren't allowed to play backgammon—only the boys were. And they could drink port. Needless to say, I did not do very well at this school. I had a big alcohol den in my room with the Iranian girls. I had a weekly pass to London, so I would go and pick up bottles. That's about it for my education. ... I stopped school pretty early, probably at about thirteen and a half, maybe fifteen. . . . My first school was Italian, and I won an award from the president of Italy for writing an essay on risparmio, which means 'the saving of money.' I was all of six years old." She laughs. "I guess it's a genetic thing."

"The tabloids totally trashed me. I thought, Fuck that I'm alive. I'm a fucking living miracle, man, What am I ashamed about?"

Aileen's black-sheep status in her family preceded her infection with AIDS, owing to her drug use—a family weakness. She has been in and out of cocaine rehabilitation clinics several times over the years, the last visit resulting in a three-week marriage to a man she met while recovering. Currently sober, she has also suffered repeated mental problems, and freely admits that she has had "a few visits in psych wards— and not with patients. I've had twelve shock treatments. Not because I've needed them, mind you, but because I have something wrong with my temporal lobes. They're not normal, which means without certain medications my brain doesn't function properly. I was willing to go to the hospital, but. . . yeah, I was put in a few times. Chris put me in a few times. I had a lot of serious problems with panic disorders. I would have very serious panic. I would have hallucinations at times. I had a few nervous breakdowns—quite a few."

I am visiting Aileen on another occasion at her Hollywood Hills home, and today she is having trouble moving around. Another of the manifestations of AIDS that she suffers from is a condition known as neuropathy, which is characterized by extensive nerve degeneration and is physically disabling. "It's real painful," she admits. "Sometimes I have problems walking. I have problems with the brain and stuff, too. It's real painful, because the nerves are exposed.... If I hold a cold drink, I feel like I'm on fire. And I fall. I fall a lot. There are periods when I'm in a wheelchair."

The jumble of Getty's house mirrors her scattered, childlike manner. In addition to her children's prominently displayed artwork, there are examples of her own attempts at agitprop. (During the opening of her 1990 show at L.A.'s Zero One Gallery on Melrose Avenue, her work so incensed one critic that he threw a brick through the gallery's front window.) The phrase "Death Row" appears throughout her work, stenciled on pieces of wood. Words by Edgar Allan Poe are written on an American flag. Deconstructed articles from her favorite magazine, Covert Action Information Bulletin, are also framed as art, and hang alongside framed letters from doctors and lawyers admonishing her for her bad behavior—as if they, too, were works to be contemplated and easily ridiculed.

Pets have the run of the house. An albino cockatiel sits inside an opened cage, its wings accidentally clipped too close and a bit of blood scabbing on its feathers, while its mate flies about and alights on the foot of Getty's bed, where she sleeps with her three dogs and two sons. Mandy, her eldest dog, a listless eleven-year-old Lab, lies on the cool tiles in the kitchen and ignores the newest, a mutt named Mickey, who stands on his hind legs in one of the many windows and yelps at the distant lights of L. A. The third dog, a six-month-old Lab pup called Mona da Vinci, sashays around the cluttered rooms.

Though her modest house is far removed from the Sutton Place manor she visited so often as a child, Aileen is cognizant of her family's mystique because of its wealth and the decadent dimensions of its tragedies. "I've always been aware of it," she admits, "but it's not a choice of mine to live within that arena." Recently, however, she has become a member of the latest celebrity category: H.I.V.I.P.'s, those who, because of their magical media-friendliness, make this most tragic of diseases somehow hip. "I do have times when it gives me, maybe, some inkling of figuring out why I was bom a Getty—so maybe I could do this," she says, realizing the seriousness of the situation. "That this is some way I could serve. And then I do feel well about myself, and the disease doesn't hurt."

Most members of Aileen Getty's family aren't so sanguine about her going public with her disease. Last October her father, for the first time in several years, invited the family, including Gail, to spend a few days with him in London, and even insisted Aileen come back for Christmas, something she was unable to do, because such a long trip is excruciatingly painful. Though J. Paul junior is seriously attempting a rapprochement with his daughter, after his long absence from her life, he has become increasingly press-shy, and will not publicly discuss her disease.

"Her father called me," recalls Judge Newsom. "I don't mind telling you this, because I'm a very close and old friend. He asked me to come over. He said, 'Bill, you're not going to believe what's happened.' I had heard some rumors, but it was the first time he had really grasped it.

He asked me to come over because I think he just needed some consolation. He's been devastated by it. . . . Maybe it's because he's had some adversity himself, but her father is profoundly sympathetic at this point."

Gail, who by all accounts has been a model mother to her children, steadfastly refuses to comment on her daughter's disease, even though both Aileen and Ariadne have pleaded with her to do so. "I've been burned a few times," Gail tells me when I telephone J. Paul Ill's house to request an interview. His nurse passes the phone to Gail, and she tells me that to attempt an interview over the phone with her son would be ill-advised because of his condition. I ask her if she herself would not reconsider and grant an interview about her daughter's brave battle against AIDS. "I've made it a policy never, never, never to talk to the press," she pleasantly insists.

"Not even for something as important as this?" I ask.

"Especially for something as important as this," she says. "There are ways that I can be of help other than giving an interview."

Los Angeles judicial commissioner John Ladner, one of Aileen's closest friends, attempts to explain the family's reluctance to discuss Aileen's illness. "I think part of this peculiarity has to do with the fact that, as fortunate as this family is financially, there has been really a lot of tragedy, to the point that I believe that one reaches one's capacity, and then one begins to build up defenses," he says. "One reaches a capacity for absorbing tragedy so that when yet another horrible event occurs—as Aileen's illness is—then it may make it more difficult for them to deal with it."

Ultimately, Aileen Getty's children are her greatest source of comfort. They are the real family members that sustain her. "One of the things that has happened as a result of her illness is that she's now a much better mother than she ever was. She worships those children," says Judge Newsom. "They are the absolute center of her life."

"I do have times when it gives me, maybe, some inkling of figuring out why I was born a Getty. This is some way I could serve."

Aileen suffered seven miscarriages before she and Christopher Wilding adopted Caleb, when he was only twenty-two hours old. "I lactated with him for a year, but I couldn't breast-feed, because I was on medication. Then I got pregnant with Andrew, but I started to lose him, so I lay down for three and a half months. One night Chris and Mom [Elizabeth Taylor] and I went out to see Purple Rain. I wasn't supposed to get up, but we just had to see Prince! So we snuck into the movie, and the next morning it was AGHHHHHHH! I had him the next day."

Taylor and her son accompanied Aileen into the delivery room. Aileen was extremely close to Taylor's ex-husband Richard Burton (Andrew's middle name is Richard), and she swears that Burton, who had recently died, was also present in the delivery room. "I think I actually talked to him when I was having Andrew. I sensed his presence. I talked out loud to him. Mom and Chris were aware of it, too. I don't know," she says, shaking her head and laughing, "maybe I have too much H.I.V. of the brain!"

Andrew's delivery seems to have been her only good experience in a hospital. Not only does she believe she acquired the AIDS virus through a transfusion during surgery, but she also has been denied treatment at an L.A. hospital because of her condition. "There's definitely not the same response to women with this disease," claims Getty. "I just haven't found that the medical care is very caring about women with AIDS."

In fact, heterosexual women are the fastest-growing AIDS demographic group, yet women are likely to manifest symptoms of AIDS differently. Their H.I.V. problems tend to be gynecological in nature—chronic yeast infections, for instance—but the Centers for Disease Control bases its definition of AIDS on studies originally made of homosexual men. Therefore, most of the infections caused by H.I.V. that women get are not included in the C.D.C. list. This results in slower diagnoses for women, a greater percentage of early deaths, and a denial of many disability benefits, since eligibility hinges on the C.D.C. definition.

"When women do get paid attention to in the AIDS crisis, it is usually as vectors of transmission," says Monica Pearl, an AIDS activist involved with women's issues who also co-authored the book Women, AIDS & Activism (South End Press) with others in the ACT UP/New York Women and AIDS Book Group. "At the last International AIDS Conference, any panel or topic of interest that had to do with women was about women as prostitutes or childbearers. There is this concern that women are passing on H.I.V. to someone else, which means that if they're passing it on, then they have it themselves. The one phrase that really bugs me is when people say 'women in their childbearing years,' because it is the leading killer for women ages twenty-five to thirty-four in New York. But people say 'childbearing years' as though we are concerned for all those potential children who are going to be H.I.V.-infected without thinking that for every H.I.V.-infected child there is an H.I.V.-infected mother."

Getty's children have consistently tested negative for the virus, as has Christopher Wilding. Getty has been quite honest with her sons concerning her illness. "They are aware of everything," she says. "Actually, they are more capable of understanding and being freer with the knowledge than any adult. They are able to respond in a lot more honest way. I only told them after I became full-blown. One of the reasons I told them was that I was pretty sick at the time and I was always in bed. I didn't want them to feel responsible for my being in bed, because kids will feel responsible for their parents' being sick, as if their actions are causing that to happen. So I wanted them to know that it had nothing to do with them, and that it was independent of them. I told them that it was AIDS. And that there wasn't a cure."

Why has she chosen, after seven years, to go public with her disease? "It deserves respect; it deserves its place. I deserve it. And I don't want a bunch of people speaking for me when I can speak perfectly well for myself and bring it the dignity it deserves. I guess what stopped me for so long is that I've just been so fearful because of the intolerance. I've just been so fearful for my children's sake, mostly—so that they wouldn't have to suffer any of the consequences."

Unlike last year's media-appointed poster heterosexual for AIDS, Kimberly Bergalis, who flatly stated at a congressional hearing before her death, "I didn't do anything wrong," as opposed to many others with the disease, Aileen does not think it is important how one contracts H.I.V. "If you got it, you got it," she says, shrugging her shoulders. "Actually, I don't really want to know for certain how I got it. That's so cruel. I never shot up, so I didn't get it that way. I mean, if you got it from a transfusion, it's more O.K. to get it? It's like, 'Oh! Your disease, it's all right. Here's a pat on the back.' 'You got it from shooting up? Then fuck you!' "

She sounds as if she has never had any shame associated with the illness. "Oh, I've felt so aware of the shame," she says, lowering her already gravelly voice to a growl as she remembers the way the tabloids handled her story last December. "Tabloids work on shame. First of all, they totally trashed me. They bring all the rubbish in. So I felt shame about every part of my life. They bring in the shock treatments and the psych wards and the drugs and the AIDS. I thought, Well, shit, just a second. Fuck that. I'm alive. I'm a fucking living miracle, man. What am I ashamed about?"

Her proud anger, however, gives way to maternal tenderness, which has begun to ache inside her these last few months with a pain even greater than that of the dread neuropathy. "I love my children like nothing else in life. I know they need me.. .but.. .1 need them more."

Suddenly, for the first time, there are tears. "I just don't want to leave them." Would she have survived this long without Andrew and Caleb? "No-o-o. Thank God for them, because they push me at times when nothing else can push me. I get up to feed them when I can't feed myself." She pauses and, wiping the tears away, calls on the crude resolve which has never failed a Getty. Fueled with it, she continues. "I'll never forget this feeling: I was about eight or nine myself, and I was with my mother in a car on the Via Veneto in Rome. My brothers and sister were in the car, too. I asked my mother about when she was going to die, and I flipped out crying and screaming. I promised that when she died, then I was going to die, that I couldn't live without my mother. The very thought of my mother dying was more than I could cope with. I think that for a child there cannot be anything worse. Fortunately, they feel comfortable enough to talk to me. I've tried very, very hard not to be elusive about anything and have some great mysterious death come into their lives. If there is a question about death, then ask it. With AIDS, we're all having to learn these new social skills of how to say good-bye to people. We are not as a species really aware or capable of acknowledging somebody else's death before it takes place."

An example: During World AIDS Day in December, two of Aileen's adored siblings, Ariadne and J. Paul III, watched a television documentary, Suzi's Story, which involved a young Australian woman's unsuccessful fight against AIDS. "We were sobbing, it was so sad," Ariadne told me later, but also confessed that she has never once mentioned Aileen's illness to her brother, because of his "tender" condition. Aileen insists, however, that Paul has a complete understanding of her illness and, because of his own afflictions, has been quite supportive in his own way. Was Ariadne telling me that she and her brother sat sobbing side by side and never once admitted that they were really crying for their sister, Aileen?

"Never," she said softly. "Isn't it incredible?"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now