Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

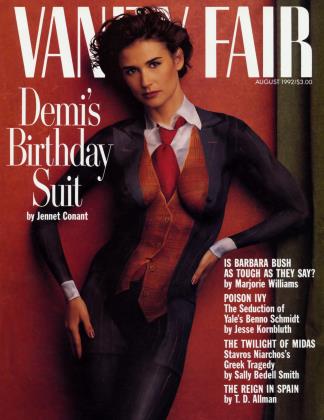

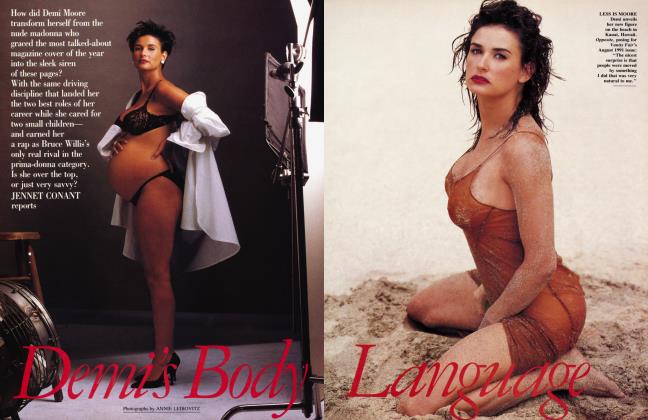

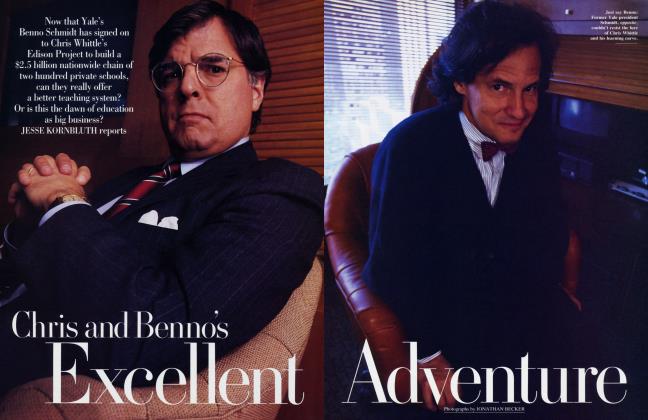

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Secrets of Midas

At eighty-three, Greek shipping billionaire Stavros Niarchos is the most compelling— and feared— of the last great monstre sacre tycoons. And as his turbulent marriages attest, he could be most ruthless with those closest to him. SALLY BEDELLS SMITH reports in an exclusive interview with the oldest Niarchos sons, who still carry out the ailing magnate's every dictate

SALLY BEDELLS SMITH

Christina Onassis susuifited murder in her mother's death and pressed for an autopsy.

Behind high walls on a narrow street in the fashionable Seventh Arrondissement of Paris is a splendid house surrounded by spacious gardens. It is known as the Hotel de Chanaleilles, and its eleven ornate salons and galleries are filled with eighteenth-century French furniture—an abundance of ormolu, marquetry, and inlaid porcelain. Above the mantel in the Grand Salon Rouge is a Gauguin copy of Manet's Olympia. Two van Goghs hang unobtrusively in the main dining room. On other walls are paintings by Vuillard, Pissarro, Renoir, and Toulouse-Lautrec. Underfoot are Savonnerie carpets designed for Louis XIV and XV. Floorto-ceiling vitrines in one room display 373 pieces of antique Puiforcat silver that will one day go to the Louvre, and the Salon de Boiserie is paneled with black lacquer chinoiserie from a Viennese castle.

But just as conspicuous as the treasures are the omissions—the unfaded rectangles on the silk walls where even greater paintings used to hang, the barren tabletops that once gleamed with rare gold boxes and Faberge bibelots, the empty vases that overflowed with lush arrangements of fresh flowers. The only personal touches are a half-dozen photos of the owner, four of his children, and his third wife, whose suspicious death on a Greek island more than twenty years ago still haunts the family. There are no pictures of his fifth wife, who died mysteriously in a small upstairs bedroom.

The owner of this grand but eerie house has barely seen it during the past decade. In its heyday, the Hotel de Chanaleilles symbolized his triumphant acceptance by the top echelon of European society, which was impressed not only by his wealth but also by his unerring taste and easy hospitality. Now the lifeless rooms echo only tragedy. They are a monument to a man who has derived more joy from possessions than from people: Stavros Spyros Niarchos. Now eighty-three, he lingers from the age of the great tycoons.

The word "tycoon" is tinged with power and ruthlessness. The men who earned this label made great fortunes, dominated the people around them, acted the way they pleased—within or without the law. Wealth was the foundation of their power, but it was the way they acted that made them tycoons. Today the number of wealthy men is probably greater than it ever was, but only a handful are still able to control— with authoritarian simplicity—huge fortunes, far-flung conglomerates, legions of executives and scores of friends who are both loyal and cowed. Among this small group, Niarchos may be the most enigmatic—and most feared.

Worth an estimated $5 billion, he is one of the richest men in the world. He is also one of the most controversial, a man of dark reputation and brilliant skill in business. His private demons drove him to drink excessively for many years, to insult his wives, mistresses, and children, to alienate a long line of would-be friends. As unlikable as he is compelling, Niarchos remains distant even from those few who consider themselves close.

He made his fortune in shipping; in the mid-1960s, he owned some eighty ships, more than anyone else in the world; today his two dozen vessels represent less than 10 percent of his worth. The cream of his art collection numbers 144 major works, mostly Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings, including eight Renoirs, six Gauguins, and six each by Degas and ToulouseLautrec. Two years ago, when Japanese industrialist Ryoei Saito paid a record $82.5 million for van Gogh's Portrait of Dr. Gachet, Niarchos inspected the painting at Christie's but declined to bid. According to his eldest son, Philip, he didn't need another portrait for his already ample collection of thirteen van Goghs. Niarchos's last major acquisition, Yo Picasso, a self-portrait, cost $43.5 million.

How the Niarchos children will eventually run the family empire is anybody's guess.

His bloodstock interests, some hundred horses at Niarchos stud farms in Normandy and Kentucky, are worth several hundred million dollars. He has vast investments in the financial markets, gold bullion, jewelry, and real estate. The luxurious Kulm Hotel in Saint-Moritz belongs to him, as do the Corvatsch ski lifts above the town. Besides Chanaleilles in Paris, he owns a chateau and a seventeenth-century manor house in Normandy, three chalets in Saint-Moritz, an apartment on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, a house on Lyford Cay in the Bahamas, and Spetsapoula, a two-thousand-acre island off the coast of Greece. His four-hundred-foot yacht, Atlantis II, worth more than $30 million, dominates the harbor of Monte Carlo.

Niarchos keeps his business empire and personal affairs fiercely private. Neither he nor anyone in his family has ever given an interview on television. Niarchos has offices in New York, London, Athens, and Monte Carlo, but these are for his minions. "What is his title—chairman?'' I asked an assistant in the New York office. "He has no title," she said. The envelope flap on his stationery has no address, either. It reads simply STAVROS s. NIARCHOS in bold engraved letters.

For years Niarchos shared the spotlight with his arch-rival, Aristotle Onassis. Both self-made men, they appeared after World War II to shake up the inbred and conservative world of Greek shipowners. The two interlopers bought tankers as others bought real estate, putting up small amounts of money and borrowing the rest. They pioneered the supertanker, which dominates ocean trade to this day. Their visibility made shipping the most glamorous business of the postwar era, until Wall Street high rollers captured the public imagination not long after Onassis died in 1975.

Niarchos and Onassis were further linked by marriage to the daughters of Greek shipping magnate Stavros Livanos. Niarchos wedded the soft and engaging Eugenie, and Onassis captured the hot-blooded Tina. After Eugenie died, Niarchos shocked the world by marrying Tina, by then divorced from Onassis.

While the two men had parallel ambitions, they were temperamentally opposite. Onassis was warm, earthy, and open, and courted publicity. Niarchos was distant, chilly, and suspicious, and demanded privacy. While Onassis might clap a friend on the back, Niarchos would extend a businesslike hand. Unlike Onassis, whose coarse features and ever present sunglasses made him seem like a gangster, Niarchos has a fine-featured, aristocratic face. Women still remark on his beautiful smooth skin; one of his lovers, a Scandinavian model named Selene Mahri, spoke fondly of his "fantastic, bony, degenerate hands."

A combination of sensuality and strength has always made Niarchos alluring to women, and he has treated seduction as an entitlement. When he was younger, he followed women in his helicopter, flattering them into bed with his attentiveness. Once, he sent his pilot to Zurich from Saint-Moritz to buy some Morati cigarettes for a South American girl who had fallen under his spell. But when he lost interest, Niarchos could be brutal. "Aren't you the pretty girl I met in Monemvasfa?" he said to an Italian model he had pursued a year earlier. "My God, you've lost your looks."

Since his fifth wife died in 1974, Niarchos has had a string of affairs with socially prominent women, including Princess Firyal of Jordan, perfume magnate Helene Rochas, and Marina Palma, the wealthy daughter of an Italian industrialist. "He would never go around with a woman who was a nobody," says one longtime friend. "He would only have a relationship with a woman who was important in her own right."

In the grand European tradition, he has lavished money on his women for apartments and jewelry. When he and Firyal broke up in the early 1980s, he left her with millions, including a house on Chapel Street in London and a flat in Paris. Marina Palma walked out on him in 1989—after he forced a confrontation by refusing to let her spend Easter with her children—and then upstaged him by returning all his gifts. But to this day Palma says that she was deeply in love with him and that no man can measure up to him.

Although he has been off the social circuit for several years, "Stavros is one of the most talked-about men," says an Englishman who knows him well. In the drawing rooms of New York and the great capitals of Europe, the doyennes of society are tantalized by the questions that have come to define the man: What part did he play in the death of his third wife? And his fifth wife? Why did he abandon the child from his fourth marriage, shotgun-style, to an American heiress? Will his other four children, once nicknamed the Niarchotics for their jet-setting ways, be able to take over his empire and hold it with the same iron grip? And ultimately, as Niarchos battles the infirmities of age, how long can he stave off death, the only force beyond his power?

Niarchos's last major acquisition, YoPicasso, cost $43.5 million.

Philip and Spyros Niarchos rise from the sofa as a butler escorts me into the large drawing room of Villa Marguns, their father's home in Saint-Moritz. The room is a disconcerting blend of rusticity and opulence. Some of the walls are paneled with rough planks from a Swiss bam, the rest are covered with a richly woven floral tapestry that is repeated on various sofas and chairs throughout the room. The coffered ceiling with intricately carved wood rosettes and moldings was designed by Renzo Mongiardino a few years ago, Philip says, "to make the room warmer."

Niarchos is attended by thirty-eightyear-old Philip and thirty-seven-yearold Spyros, his two eldest sons. If one goes away on a trip, the other remains with him. Their devotion is rooted in filial loyalty—and awe. "He says 'Jump,' they say 'How high?' " says one Greek who knows them well. "They respect him, but the attitude is very old-fashioned, very Oriental," says an Italian man who is friendly with the Niarchos sons. Observes a European who knows the family, "You meet Philip and Spyros out in the world and they are dashing young men. With their father they are like schoolboys, with eyes cast down and nervous."

On the day of my visit, their father rests upstairs. His nurse, dressed in white shirt and slacks, barely glances up as she emerges from his rooms through a paneled door. Tacked to the door is a letter chart of the sort used by eye doctors. The spacious center hallway outside is dominated by a jolting portrait of Niarchos by Julian Schnabel. Extending from floor to ceiling, and recessed behind two columns, the painting shows Niarchos against an electric-blue background, standing on the deck of the Atlantis, with two shadowy images of his face at earlier ages painted in the lower comers.

In recent years Stavros Niarchos has grown increasingly reclusive. Determined to overcome physical frailty, terrified of death, he has become obsessed with his health. Niarchos flies to Houston on his $23 million Falcon 900 for a checkup with Dr. Michael DeBakey, the renowned heart surgeon, the way an ordinary mortal visits his local internist. Two years ago he pierced one of his eyes when he fell against a television antenna, and surgery saved him from blindness. He wears thick glasses, and his hearing is impaired—both of which make him self-conscious with outsiders. He also speaks so rapidly and indistinctly that many listeners haven't a clue what he is saying.

Recently, a condition called spinal stenosis made walking difficult. In an effort to improve his mobility, he underwent back surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital last fall. His attitude toward such problems, says Philip, is "very logical." Niarchos interviewed numerous doctors about his problem, many of whom advised against surgery, until he found the man who was able to perform a successful operation. Now he follows a strict regimen of cortisone treatments, massages, exercise, and rest. "I am concentrating what little energy I have on staying alive," he told Countess Marina Cicogna, a friend since the 1950s, last summer in Venice. "I don't like to entertain guests anymore."

Philip and Spyros are polite but clearly apprehensive as we settle into an alcove of the drawing room underneath a large Monet. Two butlers serve tea from a silver service. Explains Philip, "You are the first journalist Spyros and I have ever sat down and talked to."

Both sons are small like their father, who is five feet five. Curly-haired Philip has deep-set black eyes, a ready smile, and a reserved charm reminiscent of his genteel mother, Eugenie. Spyros is his father's doppelganger, with the same thin lips and hawkish nose. Like Stavros, he speaks with a pronounced lisp. Spyros's friends have commented that, while he seems more outgoing than Philip, he has his father's suspicious nature.

When they emerge from the shadow of Stavros Niarchos, Philip and Spyros are destined to become major forces in international society. They are married to glamorous, wellborn Englishwomen who share the Guinness surname; Philip's wife, Victoria, is from the merchant-banking branch (her grandfather was wealthy jet-setter Loel Guinness), and Spyros's wife, Daphne, belongs to the Anglo-Irish brewing clan.

Philip and Spyros work each day with their father at Villa Marguns. "We do the same things. We are interchangeable," says Philip, noting that each brother is familiar with shipping, securities, real estate, and other aspects of the Niarchos empire. Their father, Philip says, is still "very active" and makes all key decisions about his business interests. He works entirely by telephone, calling on Philip and Spyros to represent him in meetings when necessary.

"One cannot be romantic about business," says Philip when asked whether they share their father's passion for shipping. Adds Spyros, "Shipping has really been in a slump since 1972." It won't be a great business again, he says, until the world economy improves. Their role in working for their father, Philip says, is to carry out his wishes and to explore new business opportunities that interest him. Following the pattern of their father, they make time in their workdays for dollops of pleasure—perhaps a couple of hours of skiing or a gathering with friends at the exclusive Corviglia Club up the hill from Suvretta. Although Philip lives down the road in a house called Relaxez-Vous, and Spyros uses Chesa Godet, another of Niarchos's houses, they often take both lunch and dinner at their father's table.

Because Niarchos is such a hermit, Philip and Spyros and their wives and children lead cloistered lives, moving from Saint-Moritz to the Atlantis II in Monte Carlo to Spetsapoula. They have barely seen the homes in Normandy, much less spent any significant time in Paris, London, or New York. "They have no choice," says a Greek friend of the sons'. "They are the empire. But they don't have lives of their own."

"To some it may seem that they are in prison," Peter Payne, a longtime Niarchos intimate who worked for him during the 1950s and who speaks frequently to him on the phone, told me. "People who don't say the best things about Stavro say he is a tyrant. I say that's not true. All right, he is an overpowering person, but these boys have a helluva good time. And remember, they love their father. ' '

Yet when I ask Philip what else he would do with his life if he could, he pauses for a moment and says almost poignantly, "I'd take a two-week vacation somewhere." There is no trace of irony as he sits in the midst of what to anyone else would be the ultimate vacation fantasy. Then he adds hastily, "It would be hard to take two weeks away when one has the business to attend to."

The other two children of Stavros and Eugenie occupy more peripheral roles. Diminutive thirty-three-year-old Maria is known as the nicest Niarchos, so down-to-earth she once worked as a "lad" in one of her father's stables. Now she efficiently runs the Niarchos bloodstock business by fax, phone, and computer from Malaysia, where she lives with her second husband, a Parisian banker named Stephan Gouaze. "She is like her father," says Rosemarie Kanzler, an old family friend. "She has lots of brains, and she is hardheaded."

The baby of the family, Constantine, is the renegade. Defiant and volatile, he was expelled from Harrow and Gordonstoun for drug-related offenses, and he recently broke off a relationship with Koo Stark, the photographer who was once linked with Prince Andrew. Friends say that thirty-year-old Constantine may be the most intelligent of the four, but he has been diminished by excessively high living. Although in the past he has been known to leak tidbits about his family to reporters, he is trying now to placate his father. "I have absolutely no comment to make," he said when I telephoned him, his cultured voice edged with fear.

As a victim, Constantine is overshadowed only by Elena, the cast-off child of Niarchos's brief fourth marriage, in 1965, to automobile heiress Charlotte Ford. Raised by her mother in New York, Elena is a stranger to her father as well as her four siblings. Now a plump twenty-six-year-old, Elena was married late last year to her partner in Stanley O's, an estate-maintenance service in Southampton, Long Island. Before announcing the engagement, Charlotte called to invite Niarchos to see his daughter and her fiance. "Yeah, yeah, yeah, I'll call you tomorrow," he replied. The call never came. Nor did he attend the wedding. "Of course he was invited," says a close friend of Charlotte's. "There was no response, not even a call to say congratulations."

A wealthy and powerful man, no matter how ruthless and difficult, can always find redemption in charm. Niarchos rarely bothers. Most people who have crossed paths with him agree on a string of unpleasant adjectives: disagreeable, arrogant, snobbish, aloof. "You never hear him saying, 'She's so dear,' or 'He's such a great guy,' " says an Englishman who has often sat at the Niarchos table. "He's brutally honest. He doesn't give a damn about antagonizing people." As a consequence, many find him frightening. "He is very cerebral, and not very human," says one New York socialite. "He doesn't seem to connect with the needs of other people."

When Niarchos sets his mind on something, he lets nothing get in his way. "He doesn't have to consider any consequences," explains an Italian friend. Some years ago he bought a house on Lyford Cay sight unseen. Since he never stayed there, he told his office to rent it out—until one day he decided to have a look. "But it's rented," his people told him. "Get them out," replied Niarchos. He ended up staying only for the weekend.

His temper can flare over trifles. Once, on his airplane, Niarchos asked an aide to open a two-thirds-of-a-pound tin of caviar. When he detected that someone had eaten a small amount, he threw the entire tin away. "He was Jekyll and Hyde," says a woman who knew him intimately. "He was always mysterious. You never knew what he would do from one moment to the next. He could change with just one phone call."

Nor is the fabled "Golden Greek" known for much of a sense of humor, particularly about himself. One New Yorker recalls visiting Niarchos at his suite in the Waldorf Towers. The man glanced at the obviously mediocre paintings on the walls and noted ironically, "I see you've brought some of your collection with you." Niarchos, says the man, ''gave me a look of absolute rage."

"What is his title—chairman?" I asked a Niarchos assistant. "He has no title."

His intense self-involvement can be tiresome. A Greek journalist, Helen Vlachos, described him as ''one of the few genuinely boring clever men that I have ever met. Maybe it is the jarring quality of his voice, maybe his persistent obsession with whatever is his interest of the moment, and his tireless, monotonous repetition of what he has on his mind. He does not really care if you are interested or not."

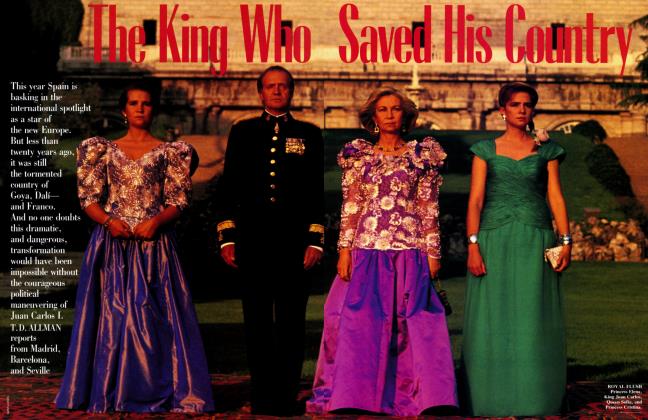

Yet Niarchos's rise to the top of international society was based on more than the size of his bank account. He courted the Duke and Duchess of Windsor so assiduously that the Duchess remarked to a fellow guest on the Niarchos yacht, "He must really be a snob, because we're both so boring." The small circle of Niarchos friends now includes Fiat chairman Gianni Agnelli, the Duke of Beaufort, and King Juan Carlos of Spain. With Agnelli, says Peter Payne, "there is no jealousy. They both lead the same sort of tycoon life." But, adds Payne, "Agnelli is an industrialist, with responsibilities, labor unions, the Italian political game. Nothing encumbers Niarchos. That is an enormous source of power."

Intimates say Niarchos is misunderstood because he is a nonconformist who has stubbornly chosen to keep his life private. Says one woman who has been close to the Niarchos family, "They are private not because they love being mysterious but because they don't want to be uncomfortable. They like only close friends, people they can trust. Stavros is a moody S.O.B., but he is not mean to everyone." His direct manner, says Denise Thyssen, another old friend, "makes him actually quite down-to-earth." Peter Payne claims that in quiet, relaxed moments Niarchos is "one of the wittiest men." A business associate of long standing notes that Niarchos has lent his artwork generously over the years, but "he has received no credit because he always does so anonymously." Rosemarie Kanzler, for five decades a prominent fixture on the international social circuit, says, "If somebody is in the hole, he would try to get them out. He helped me in my last divorce."

Yet friendship with Niarchos can be a one-way street. "In conversation he won't listen to you," says one Italian friend. "He is funny that way. He shows affection by asking a few questions about how things are, but it's a quick survey and on to something else." To join the Niarchos circle, one has to accept his insistence on loyalty and privacy—and recognize, as Peter Payne puts it, that "he knows he can always call me up, no matter what time.

The Niarchos charm, such as it is, springs not from personality but from power, and the quirky style that comes with it. His attention to detail can be astonishing. In 1987 he gave a luncheon at Chanaleilles on the occasion of his son Spyros's marriage to Daphne Guinness. "Every time one glanced at a painting, a servant came over and whispered who painted it and in what year,'' recalled one awestruck guest.

As a host, Niarchos is famous for creating an atmosphere of ultimate self-indulgence and security. "You are under his wing, and you feel nothing is going to happen to you, he is so powerful,'' says an Italian man who used to call Niarchos "Goldfinger.'' "It is a magic feeling, like being on another planet." British friends still talk about the time the Duke of Marlborough asked for a glass of port after dinner on Niarchos's island, Spetsapoula, and was told there was none. The next night the butler said to the duke, "Here is a glass of port for Your Grace." Niarchos had had a bottle flown in from Paris.

"Stavros is unbelievably unbearable, but in an odd way I have respect for him," says Marina Cicogna, reflecting the sentiments of other friends as well. "He has always lived his own life. Whatever he has done has been strange, but at a high level. I find him totally different from anybody else, totally original, and very intelligent."

'Stavros is sort of a wellborn Greek," one wellborn Englishman told me emphatical"He was originally a Greek naval officer." Well, yes and no. Although Niarchos has never denied having made his own fortune, he has fostered the impression that he had proud origins. Actually, his father's family were peasants from a tiny village

outside Sparta who immigrated to the United States in the late nineteenth century. They settled in Buffalo, where his father operated a candy store with NIARCHOS displayed in neon lights above the door. On a visit to Greece, a newly prosperous Spyros Niarchos attracted the attention of Eugenia Coumandaros, whose middle-class family ran a successful grain-and-feed business in Sparta.

Spyros took his bride to America but returned to Greece several years later, when she grew homesick. Using the money he had made in Buffalo, he invested in the Coumandaros flour mill in the seacoast town of Piraeus. He and his brothers-in-law made enough money to send young Stavros to private school.

When Stavros Niarchos was fourteen, his father went bankrupt after speculating in the stock market. Stavros transferred to a public school, and, later, the family was so pinched that he was unable to complete his studies at the University of Athens. Instead, he took a job at the flour mill owned by his uncles.

(Continued on page 181)

(Continued from page 137)

He worked hard, making money and using his uncles' connections to join the Royal Greek Yacht Club. He learned to sail on a cousin's yacht, and he bought a flashy Bugatti. With black sheets on his bed and mirrors on his walls and ceiling, he became a notorious ladies' man. At age twenty-one he married Helen Sporides, the daughter of an admiral who found Niarchos so unsuitable that he insisted the marriage be dissolved after less than a month.

While in his twenties, Stavros Niarchos conjured up the role he would play in life—a powerful businessman who would become a great gentleman, a Maecenas to artists, and the social equal of European aristocrats. His fortune, he decided, would come from shipping. Since Greece had no real aristocracy, the shipping establishment—tightly knit families with names such as Embiricos, Goulandris, Kulukundis, and Mavroleon—came closest to approximating society. But shipowning passed from father to son, so Niarchos had to find his own way. He prodded his uncles to buy some freighters. When his family refused to expand further, he raised money and bought one of his uncles' ships through a London agent. In the first year of World War II, Niarchos's ship was bombed by the Luftwaffe. For an investment of $60,000, the wily Niarchos collected nearly $1 million in insurance.

By then he was married to Melpomene Capparis, the twenty-year-old widow of a Greek diplomat. She was small and slender, with a classic profile and a lively wit. Her family had once been wealthy, so she was as well educated and cultivated as she was beautiful. Fellow Greek Helen Vlachos concluded that "Stavros admired Melpo more than he really loved her."

The couple moved to New York, where Niarchos paid $43,000 for an estate in Lloyd Neck, Long Island, that they filled with art, antique furniture, and silver. He continued to buy ships and make profits on the insurance when they were sunk. His membership in the Royal Greek Yacht Club gave him officer rank in the Greek navy, but he spent little of his tour of duty at sea. He shuttled from Manhattan to the Ritz Hotel in London to a house with a staff of three in Alexandria, Egypt, where he worked at the headquarters of the Greek government in exile.

Back in New York after the war, he bought old Victory and Liberty ships at bargain prices, sold them for tidy profits, and soon owned a fleet of war-surplus tankers that he had purchased through American holding companies. Not only did he pay a fraction of what it would have cost to build them, but he also avoided U.S. taxes by leasing his ships to a Panamanian company. That maneuver prompted a Justice Department investigation several years later. Niarchos settled and paid several million dollars in fines.

Niarchos and Onassis vaulted into the major leagues by building bigger and bigger tankers to transport oil. To finance the construction, both men persuaded the American oil companies to sign long-term charters. Using the charters as collateral, Niarchos and Onassis secured loans from major U.S. insurance companies.

As Niarchos counted his millions, his marriage to Melpomene disintegrated. "She wanted to show she was cultured, and made fun of him in conversations," recalled a Greek friend from those days. "She put him down, or, rather, tried to." Her refusal to submit to his dominance infuriated Niarchos.

He took an apartment in Manhattan, where he romanced a Scandinavian model named Selene Mahri. They dined at El Morocco and the Stork Club, and he set her up stylishly, buying her two homes, a car, and two poodles in addition to the requisite jewelry. When they parted, she kept only the poodles, although he later gave her two Corots as a gift when she married Michigan millionaire John Wendell Anderson III.

In Greece, arranged marriages have long served to keep strangers out, to preserve fortunes, and to hold women down. "Women even in the richest Greek families married whomever they were told. Most were reasonably happy. They were brought up for that," a Greek man from an old shipping family told me. For Tina and Eugenie Livanos, only the selection of two wealthy upstarts was somewhat unconventional.

Aristotle Onassis and Stavros Niarchos met their future wives while currying the favor of the young women's father, Greek shipping titan Stavros Livanos. He had left London at the outbreak of World War II and settled in New York City, in luxurious quarters at the Plaza hotel. Although he lived well on his estimated $200 million fortune, Livanos was at heart a skinflint. He rode the subway to work, picking up each day's copy of The New York Times from the subway platform rather than paying for it. Once, a Niarchos associate encountered him on a train to Baltimore. Years later, the associate was still incredulous over what happened next: "Livanos asked me to have coffee with him. Before we arrived, the waiter on the train came with the bill. Livanos said, 'Separate bills.' For coffee!"

Like others of his generation, Livanos had bought his ships with his own money. He took a dim view of the high-flying financial schemes Niarchos and Onassis were using to build their empires, although he was impressed by their energetic shrewdness. When Niarchos wooed fourteen-year-old Tina, Livanos seized the easy excuse that she was too young to marry a man not even divorced from his second wife. Two years later Onassis asked to marry Tina, and Livanos balked again, but then offered the hand of her older sister, Eugenie, instead. (Onassis later observed that Livanos "regarded his daughters like ships and wanted to dispose of the first of the line first.") Onassis insisted on Tina, and they were married at the end of 1946. She was seventeen, he was forty. Less than a year later, thirtyeight-year-old Niarchos and Eugenie, twenty-one, were married in the same Greek Orthodox cathedral in Manhattan.

"The father was not happy about either of the marriages," one well-connected Greek man explained to me. "He would have aspired to have them marry more status in the Greek community. These two were up-and-coming but not very polished characters." Livanos's wife, Arietta, a stylish woman with a penchant for dark glasses, took a more practical approach. "The wife ruled in that family," continued my Greek source. "She accepted both proposals. That was her area, her daughters, and she pushed the old man to say O.K."

It has often been said that Niarchos was not entirely happy with the outcome, either. He had seen Tina first, and Onassis had snagged her, fueling the rivalry between the two iron-willed men. Yet the dark-haired and delicately pretty Eugenie seemed the perfect wife for Niarchos. She and her sister were educated at the exclusive Heathfield School in England, finishing at Miss Hewitt's Classes in New York. They spoke English with a British accent and were fluent in French. Eugenie was reserved but charming, and she carried herself with great dignity. She made the ideal hostess for Niarchos's planned ascent into the upper reaches of European society when he moved his headquarters to London in 1949.

Their first step was acquiring totems of status. They began modestly, with several Renoirs, a small van Gogh costing $25,000, and a magnificent Pieta by El Greco that Niarchos bought for $400,000 to celebrate New Year's Eve in 1954. "I can sit for hours looking and always discovering new details," he once said. "I like gay, relaxing paintings. I find peace looking at them, watching beautiful things."

The capstone of his collection was the extraordinary haul he made in 1957, when he paid $3 million for fifty-eight paintings and one sculpture that Hollywood actor Edward G. Robinson, a noted collector, was forced to sell in a divorce settlement. Niarchos placed his bid by telephone from Saint-Moritz after Eugenie had flown incognito to Los Angeles for a firsthand look.

The best paintings hung in the Creole, the black-hulled, three-masted Niarchos yacht. At 190 feet, with teak decks, mahogany paneling, and polished brass fittings, the Creole was considered one of the most beautiful boats on the Cote d'Azur. For some years, Niarchos insisted that his priceless art was safe from the salt air in temperature-controlled salons, but then he quietly moved the paintings ashore. "One could put a Boudin on a yacht but not a Renoir," he explained to friends with typical hauteur.

Niarchos carefully positioned himself at the essential stations of the jet set's yearly progress. In the winter he and Eugenie parked at the Palace Hotel in Saint-Moritz, where he rented five extra rooms for the crew of his Dakota airplane, which used the frozen lake as a landing strip. Frequently he paid the orchestra to play in the Palace bar until seven in the morning.

"It was very amusing," recalled Jimmy Douglas, a wealthy American expatriate. "He would get quite drunk and yell 'God bless America' over and over because of some American tax setup he was taking advantage of."

In 1954, Niarchos paid $575,000 for the forty-two-room Chateau de la Croe at Cap d'Antibes, which had previously been rented by King Leopold of Belgium, Queen Helen of Romania, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor—and Ari and Tina Onassis. Overlooking the ocean, surrounded by twenty-five acres of lawns and gardens, the chateau had a grand portico and marble columns. In the drawing room, the ceiling slid open to reveal the sky. But Stavros and Eugenie used the chateau primarily for guests, preferring to live in the two-story gatekeeper's house.

Four years later Niarchos bought the island of Spetsapoula, which he transformed into a paradise for shooting parties. In addition to the main, L-shaped villa, he built fifteen guest cottages; a grotto with sauna, rock pool, dressing rooms, and exercise machines; a cinema; and beaches with imported sand. The island was stocked with thousands of pheasant, quail, and partridge. During the shoots, the birds were driven out above the cliffs as a fleet of Chris Crafts circled below to pluck them from the water when they dropped. Between drives, everyone would take a swim. Little wonder that kings, queens, and dukes signed on for the Niarchos shoots a year in advance.

Chanaleilles, however, was the masterpiece that Niarchos used to define himself. Beyond the initial cost of $500,000, Niarchos spent twice that amount on the three-year restoration by the architect Emiglio Terry. The curtains alone, including specially woven lace replicas of those made for Marie Antoinette at Versailles, cost several hundred thousand dollars.

Strategic alliances helped Niarchos solidify his social position. He formed a partnership with socialite Loel Guinness to build a ski lift in Saint-Moritz from the Corviglia Club to the Piz Nair summit. He invited the Duchess of Kent and other highborn women to christen his ships, giving them diamond bracelets and gold Faberge cigarette boxes for their trouble. And he put on his payroll aristocrats such as Prince Alexander of Yugoslavia, Count George Theotoki of Greece (known for his refrain "I would die for the boss"), and the Marquess of Milford Haven, nephew of Lord Louis Mountbatten. Suspecting the motive behind the hiring, Mountbatten asked an associate of Niarchos's for assurances that the marquess would not be used for social purposes. Niarchos insisted on taking him on junkets to Saint-Moritz anyway.

For purely ingratiating gestures, nothing could top the back-to-back cruises Niarchos bankrolled in 1954 and 1955. The first was for royalty only, with a guest list headed by Queen Frederika of Greece. The following summer he gave the famed party organizer Elsa Maxwell $90,000 to charter a yacht and invite the best of European society. With 120 celebrities from six countries aboard, the Achilleus sailed through the Aegean for two weeks in a great blast of publicity. "He didn't know most of those on board," recalled one passenger, "but he wanted to." Yet Niarchos was much too clever to travel with his guests. Instead, he cruised nearby on the Creole, making just enough appearances to create a mystique.

He was impeccable in providing the surroundings of hospitality, yet he offered little of himself. On Creole cruises, whitegloved stewards fussed over guests while Niarchos remained on his deck, reading telexes or meeting with aides. "We never saw Stavros before noon," says a French countess. "Then he gave all the latest news at lunch and talked about Wall Street with the men. He had his day organized. He would work, then appear. Then work. I always wondered why he invited us. I could never have real contact with him. We were part of the scenery."

In those early days, Niarchos had a mischievous streak and a fondness for pranks. When socialite Drue Heinz gave a party in Saint-Moritz and asked guests to come as their "repressed desire," Niarchos showed up dressed as a Boy Scout. During the Achilleus cruise, he briefly fooled the passengers into thinking that Corfu had been rocked by an earthquake. When they finally went ashore, he disguised himself as a bartender who clumsily stuck his fingers into everyone's drinks. "For Stavros, you had to have a sense of humor and answer quick," says a French aristocrat. "Otherwise, he wouldn't bother to talk to you."

In awkward situations, Eugenie's patient manner helped smooth the way. "I think Eugenie adored him," says Drue Heinz, who sailed several times on the Creole. "Greek women are different, very supplicant, and she seemed happy. They were in cahoots—a team."

Niarchos rewarded Eugenie's forbearance by showering her with jewels. When their first child, Philip, was bom, he gave her a $100,000 emerald necklace. Several years later he paid $1 million for a 128carat diamond. "It used to embarrass her," recalls Marina Cicogna. "When she wore it, she always hid it under a bow in her dress. We would make a sign across the room, and she would lift the bow and flash the diamond as if it were something dirty. She was funny like that."

Yet beneath the surface gaiety were traces of sadness. "Eugenie always thought she was the ugly duckling, and Tina the bubbly and sexy beauty," says Marina Cicogna. Her self-esteem sank lower with her husband's relentless womanizing. Jimmy Douglas recalled the time back in the late 1950s when he was dancing with Eugenie at the Palace Hotel: "She told me how unhappy she was that Stavros was looking at another girl. I remember I was very surprised she said that. Then she said, 'All of my friends told me never to marry Stavros.' She seemed close to tears."

Once Niarchos had attained his goals of vast wealth and secure social position, the chip on his shoulder only grew larger. He became more remote and deeply mistrustful. "He is very reticent to say anything about himself or how he feels," says Rosemarie Kanzler. "He has never shown his feelings."

Some acquaintances believe his indifference to others stems from his early days. Niarchos doted on his mother but seldom spoke of his father. Colleagues remember the time Niarchos launched his 30,000-ton tanker, World Peace. Among the large crowd of dignitaries was an elderly man who came without an invitation. As Doris Lilly recounted the scene in her book Those Fabulous Greeks, the old man introduced himself to the port captain as Spyros Niarchos and announced that he was looking for his son. When the captain reported this to Stavros, "he was told to take the old man to the room of the chief engineer and give him lunch, but keep him there."

While Niarchos has absolute self-confidence as a businessman, some who have been close to him say he is less certain of himself in social settings. One impediment, says a former colleague, is that "he couldn't handle languages well." Niarchos has been somewhat deaf since he was young, and he has a nasal timbre combined with a lisp that muffles his words, as if he were speaking with a mouthful of food. Those who spent a lot of time with him learned to decode and comprehend, almost like acquiring a language. But with strangers his speech impediment became a barrier. "He would be furious if he would say something and you would say 'What?' He would get very mad at you," says one Frenchwoman. As a result, he rarely engaged in more than perfunctory conversations.

By creating his own world, Niarchos could avoid dealing with fools and knaves. "He wants to be surrounded by intelligent people," says Rosemarie Kanzler. "Others who don't give him anything special he doesn't want." Yet as he had to deal less and less with day-today problems, he became more abstract, and all his personal relations took on an air of unreality.

Success reinforced Niarchos's belief that he could make it on his own. "He would talk with people, but very little," says one Greek who worked with him for more than a decade. "It all came from him. He had a partner or two, but they had no influence. He did it himself."

Niarchos has never bothered to conceal the effort he gives to his business. Even on safari, he used to have packets of information dropped into the bush. "In his mind, work was the center of his life," says one former longtime associate. "His extreme intelligence was concentrated on the business. He would pass serious and penetrating judgments on people with just one sentence."

Some years ago Niarchos was entertaining British friends on Spetsapoula, along with a tiresome German shipbuilder and his wife. The weather was very hot, and Niarchos served one course of rich food after another. After two straight days of foie gras in virtually every dish, one of the British guests asked about the menu. Replied Niarchos, "You don't realize the German is very greedy, and I am trying to make a deal. In a day or two he will have such terrible indigestion that he will be vulnerable."

This total absorption with business wears down his associates, but many have stayed with Niarchos for long periods nevertheless. Marke Zervudachi, who oversees his art collection and other investments in London, has served him for forty years. Niarchos's subordinates thrive on his constant stimulation, with the knowledge that his storms of temper pass quickly and that he generously rewards good work. Says Peter Payne, "It is like what they say about the Caterpillar marine engine. The rougher you treat them, the better they are. But they have a tremendous sense of loyalty, and he has enormous power over them."

She might have been just another beautiful diversion, but the twenty-fouryear-old daughter of magnate Henry Ford II thrust Stavros Niarchos into his first major scandal. Growing up in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, Charlotte Ford had led a sheltered life. For twelve years she attended a convent school, where she went to Mass each day and was subjected to periods of enforced silence. After her splashy $250,000 debut, her father decided it was time she had some fun, so he took her to Europe.

Niarchos saw her at a party in SaintMoritz early in 1965. "Did you notice how Stavros was looking at you?" her stepmother, Cristina Ford, said afterward. She had, and after Eugenie left the next day, Charlotte and Stavros skied together regularly and went out every night. Niarchos dazzled her with his stylish, extravagant life. The following summer, her father chartered a 212-foot yacht, the Shemara, and Niarchos followed behind in the Creole. He helicoptered in and out, single-mindedly pursuing Charlotte, flattering her, giving her lovely jewels for no particular reason, and eventually taking her to bed.

By the autumn, Charlotte was pregnant. Henry Ford flew to London for a meeting with Niarchos, who agreed to marry her. At the time, Niarchos could not enter the United States, because of tax problems. It has long been rumored that President Lyndon Johnson helped prod Niarchos into marriage by assuring him that the government would Find a way to resolve his situation. In fact, several months after Niarchos married Charlotte, the U.S. government announced a financial settlement with Niarchos, and he could again operate freely in America. The reason, says a source close to Charlotte, was "Henry Ford's friendship with L.B.J."

The wedding and its aftermath were surreal, even by the jaded standards of the international jet set. A few days after Eugenie granted Niarchos a divorce in December 1965 in Juarez, Mexico, a Ford-company plane whisked in Charlotte and a Niarchos aide. Niarchos came from Canada on a second company plane. For still-unfathomable reasons, Niarchos scheduled the marriage to take place at midnight in a suite of a Juarez motel. Before the ceremony, Niarchos pulled a forty-carat diamond (nicknamed "the skating rink" by the Fords) from an envelope, threw it at Charlotte, and said, "Here's your wedding ring." She pointed out that a simple band would suffice, so they used one she was already wearing.

A chartered 707 took them to Switzerland. Stavros and Charlotte moved into the honeymoon suite on the top floor of the Palace Hotel in Saint-Moritz, while Eugenie and the four children stayed in the Niarchos chalet. Every day Niarchos would go home to work, leaving Charlotte on her own. At midday she would meet him for lunch at the Corviglia Club, and he would spend the afternoon skiing with Eugenie and the children. The menage a trois stirred up a tabloid frenzy that would have made Donald, Ivana, and Marla blush. But when Charlotte went on outings arranged by Caprice Badrutt, wife of the owner of the Palace, Niarchos had a fit of jealousy. He accused Badrutt of trying to fix Charlotte up with other men, and he insisted that his wife cut off contact with her.

The newlyweds saw each other only intermittently over the next few months as Charlotte returned to Manhattan to redecorate the Niarchos triplex apartment on Sutton Place. His mother lived in the apartment below and hardly made Charlotte feel welcome. "I'll never forget the things Stavros's mother said to me. She accused me of bewitching him, of deranging his mind," Charlotte later told The New York Times.

After Elena's birth in May, Charlotte took her to Chateau de la Croe, only to learn that Niarchos had gone on a safari with Philip. Her husband made a few perfunctory visits before Walter Saunders, head of the Niarchos New York office, arrived in Cap d'Antibes to say his boss wanted a divorce.

The following March, Charlotte was back in Juarez. When she returned to her apartment, Niarchos had left word that she must phone him immediately. "I tried to call to get you to stop," he said. "It's done, my dear," she replied. He proceeded to seduce her all over again. She cruised with him on the Creole, and he gave her bracelets, rings, and earrings of rubies, diamonds, and emeralds until his interest expired. "My mistake was in being too submissive," Charlotte said several years later.

"If you fell into the hands of Stavros S. Niarchos, you had to be very well prepared," says one Italian man who knew them both. "Charlotte was naive. She couldn't do anything. She was squeezed like a lemon." The strain took its toll when Charlotte contracted Bell's palsy, a virus that paralyzed the right side of her face. Her doctors told her it was caused by stress. Although she recovered, the disease left her with some permanent nerve damage.

For several years following the divorce, Niarchos paid attention to their daughter, Elena. During the summer of 1969, he had her for two months on Spetsapoula. But otherwise, he would see her only at brief meetings in Nassau. "It was a disaster," recalled a close friend of Charlotte's. "They couldn't understand each other, and Elena would come back depressed." Sometimes he would arrive suddenly for tea in New York, but Elena was too uneasy even to sit on his lap.

Niarchos insists that he cut off contact with her twelve years ago because she wanted to use Ford as her surname. Friends of Charlotte's say the rupture occurred even earlier, mainly because the other children found Elena's presence disturbing. Her only recent encounter with any of her siblings took place several years ago, when she met Constantine by chance in a New York bar. He screamed at her, upsetting her terribly, and Niarchos called the next day to apologize.

Charlotte has told friends that Niarchos has rejected Elena's various efforts to contact him. "He couldn't deal with the guilt, ' ' Charlotte has said. But acknowledging his feelings would be equally impossible. Notes one source close to Charlotte, "I don't think he is capable of allowing himself to do that. It would show weakness. And he might not like what he saw."

With Charlotte out of the picture, Niarchos resumed his life with Eugenie. The Greek Orthodox Church recognized neither his Juarez divorce from Eugenie nor his marriage to Charlotte, so he and Eugenie never went through the formality of a second marriage ceremony. Why did she take him back? The children were obviously paramount. But there was another factor. Says Rosemarie Kanzler, "Eugenie was quite agreeable. She knew he would come back to her. She told me herself. She said he promised to come back after a year."

Still, friends say Eugenie never recovered from the experience. The womanizing continued unabated, albeit more discreetly. Greek journalist Taki Theodoracopoulos contends that Eugenie should have understood that her husband's behavior reflected the "male-dominated macho Greek culture. A man is expected to womanize." Although Eugenie didn't complain publicly, she started taking sedatives. She became more withdrawn, sitting quietly in a comer during parties instead of mingling as she had in earlier days.

On May 3, 1970, Eugenie Niarchos walked into her husband's office in their villa on Spetsapoula and found her husband on the telephone talking to Charlotte Ford. It was midaftemoon in New York, sometime after ten at night in Greece. He had called his ex-wife on impulse to say hello and inquire about three-year-old Elena. He had no particular purpose, Charlotte told friends, and she knew he had been drinking, because he repeated himself and slurred his words more than usual. After a conversation of less than ten minutes, Charlotte hung up, nonplussed.

A Niarchos spokesman would later say that Eugenie "misunderstood the intent of the call," which prompted a fierce argument about whether Elena should return to the island that summer. According to one report, they also fought over a request from Eugenie for "a large sum of money" for a member of her family that Niarchos had rebuffed.

She stormed into her bedroom, where shortly before eleven P.M. a maid found her lying unconscious next to her bed, with an empty bottle of Seconal nearby. Niarchos later told authorities that he had tried desperately to revive Eugenie by slapping her face, shaking her shoulders, splashing her with water, putting his finger down her throat to make her vomit, and, with the assistance of his valet, trying to force hot coffee into her mouth. Rather than immediately summoning help from the island of Spetse, a ten-minute boat ride away, Niarchos waited a halfhour before phoning Athens for his shipboard doctor. By the time the physician arrived by helicopter ninety minutes later, Eugenie, aged forty-four, was dead.

Because of the numerous bruises on her body, the doctor refused to sign a death certificate, and police inspectors ordered her body sent to Athens for an autopsy. The report concluded she had died after swallowing twenty-five Seconals. The panel of forensic specialists also detailed the extensive injuries to her body, including bruises on her throat, arms, and legs; internal bleeding in several places on her back and stomach; a large bruise and swelling by her'left eye. Since Niarchos said she had fallen to the floor several times and he had grabbed her by the neck, the autopsy concluded that the injuries resulted from his frantic attempts at resuscitation. But the examining doctors also cited an "inexplicable and inexcusable delay in calling a doctor." And several news accounts said that one finding, not officially revealed, was a ruptured spleen.

That August the public prosecutor in Piraeus ordered a second autopsy, which concluded that the level of barbiturates in Eugenie's blood was not lethal, and that she had died as a result of injuries. Yet another inquiry suggested that Eugenie had been given the Seconals by force. The prosecutor recommended that Niarchos be charged with fatally injuring his wife—the equivalent of second-degree murder. One important individual pushing for a prosecution was Ari Onassis, who was bidding against Niarchos for a multimillion-dollar business contract with the Greek government. Less than a month later a three-judge panel in Piraeus rejected the criminal charges. This finding was upheld by the Athens High Court, which concluded that Eugenie had killed herself.

Five years later, an assistant prosecutor named George Xenakis charged that judges, doctors, and police officials had covered up Eugenie's murder. He contended that Niarchos had hit her in the face, kicked her in the abdomen, tried to strangle her, and then given her Seconals in an amount insufficient to kill her. No formal charges were brought against any of those involved in the alleged cover-up. Yet with so many unanswered questions, the cloud over Niarchos never dissipated.

Still, twenty years later, the proponents of the suicide theory seem to have the edge. Eugenie had tried to take her life in Saint-Moritz several years earlier, and she suffered from bouts of deep depression. "It was definitely a suicide," says one former close associate of Niarchos's. "I have read all the papers, and from a legal point of view it was suicide. When you are in that condition and someone handles you, it leaves bruises." Eugenie did leave a note, but it was cryptic and did not say she intended to take her life. Scrawled in red pencil, it said, "For the first time in all our life together I have begged you to help me. I have implored you. The error is mine. But sometimes one must forgive and forget." A nearly illegible postscript in ballpoint pen reads, "26 is an unlucky number. It is the double of 12.10b of whisky."

The essential question is whether Niarchos drove his fragile wife toward suicide with mental cruelty. One close friend contends that, her husband aside, Eugenie was "a depressive woman. She was always too quiet, never gay, not a conversationalist." But Constantine, the youngest and most outspoken son, has said that his father "broke Eugenie's spirit."

Niarchos seemed a beaten man in the months following Eugenie's death. Confined to Greece during the murder inquiries, he appeared haggard and distracted. His nephew said he had a "nervous breakdown." He pulled himself together, as always, by throwing himself back into his work.

By ski season in Saint-Moritz he had rebounded. On his arm was the beautiful former wife of the actor Yul Brynner. Doris Brynner moved into Villa Marguns, prompting the gossips to nickname her "the nanny," because she seemed determined to ingratiate herself with Niarchos by assuming the role of hostess and governess. Niarchos had no interest in her as a wife, but maintained a cordial friendship.

Alert eyes had already caught the growing closeness between Niarchos and Eugenie's sister, Tina. Divorced from Onassis since 1959, she was married to the Marquess of Blandford, the future eleventh Duke of Marlborough, but she had begun to tire of the horse-and-hounds life at the Blandford estate, Lee Place. Since Eugenie's death, she had taken her sister's two youngest children to live with her in London.

If there were any lingering doubts about Niarchos in the Livanos family, the formidable matriarch, Arietta, suppressed them. Her order to close ranks even while he was under suspicion demonstrates the self-protective nature of Greek families. It was Arietta who pushed her daughter toward Niarchos in an effort to further unite the families and their fortunes.

Tina had been the first choice of Niarchos decades earlier, and over the years they often skied together and flirted. "Tina was petite, gay, fun-loving, full of laughter, like a little bird. Stavros always preferred her," says Anne-Marie d'Estainville, who often joined them on the slopes. Before Eugenie died, she had even accused Niarchos of having an affair with Tina, which both of them denied.

With Tina whispering to friends her suspicions about Niarchos's role in Eugenie's death, she hardly seemed inclined to be his wife. But in a letter to a close friend, Tina revealed that Eugenie had said that if anything happened to her, Tina should marry Niarchos to look after the children. Following her divorce from Blandford in May 1971, Tina shared a house in Villefranche on the Riviera with her brother, George Livanos. She sailed with Niarchos on the Creole, he came to her villa, and they dined frequently at Chateau Madrid in the hills above the Mediterranean. In September they went to a spa in Quiberon, Brittany. Between hot sea baths and massages, they took long walks and talked quietly over meals. After ten days they flew to Lausanne, Switzerland, to tell her delighted mother that they would marry.

Their ten-minute wedding in a town hall in Paris was as carefully planned as a top-secret military maneuver. Assisted by his close friend Peter Payne, Niarchos eluded reporters by changing cars several times, while his lawyer escorted Tina and her mother. Friends say Niarchos hoped that the marriage would convince doubters that he was innocent of Eugenie's death.

Tina and Stavros still ran on the social fast track. Niarchos sold the Creole and built an elaborate new yacht, the 385-foot Atlantis. With accommodations for twenty-two guests and fifty crew members, it had five decks and a helicopter landing pad, an oval swimming pool, a gymnasium, a cinema seating forty, and a garage for his blue Rolls-Royce and Volkswagen Karmann Ghia. But such touches as a chrome fireplace and bedsheets in hues matching the paintings on guest-room walls seemed vulgar compared with the sleek Creole.

Tina changed, too. Only months after her marriage, friends noticed that she appeared subdued. Both her children had stopped speaking to her. Christina and Alexander Onassis were furious that she had married their father's sworn enemy. According to British society columnist Nigel Dempster, Christina told her husband, Joseph Bolker, "Stavros killed Eugenie, and he's going to kill my mother." To ease the tension, Tina followed her sister's path and turned to barbiturates.

In January 1973, Alexander Onassis was killed in a plane crash, and Tina fell apart. On the Atlantis, she would lock herself in her cabin, listening to a tape of his voice for ten hours straight. At dinners and parties, she seldom said a word; her hands shook, and her face looked puffy. She was drinking heavily and taking even more pills. Late in the summer of 1974, one New York socialite saw her at dinner in the South of France. "She seemed sedated," he said. "I thought, How unlike Tina. She's out of it."

Shortly after Stavros and Tina arrived in Paris in early October, Tina had lunch at the apartment of Anne-Marie d'Estainville. "She opened her bag and took out all these pills—red, green, yellow, and blue," recalled d'Estainville. "She said, 'My nerves are so bad after Alexander's death, and I am so unhappy about my life.' " She also complained that AnneMarie's sister, Helene, had seemed too familiar with Niarchos on the Atlantis several weeks earlier. Anne-Marie assured her they were not having an affair, and she made Tina flush the pills down the toilet.

Tina's spirits lifted when Anne-Marie took her to an atelier, where Tina bought two mink bedcovers for Stavros and Philip at half-price. Tina seemed in even better spirits at a luncheon several days later with a group of women. "She had just bought seventeen dresses, had her hair done and her face beautifully made up," says Rosemarie Kanzler. "You don't do that when you don't want to live."

The next morning, on October 10, Tina was found dead in her bedroom at Chanaleilles by a chambermaid who was bringing her breakfast. She was forty-four years old. Comparisons to the tragedy nearly four years earlier were inevitably drawn. There were no marks on her body, and no suicide note. Niarchos had been sleeping in his own bedroom, but inexplicably he waited more than twenty-four hours before announcing her death. Confusion over the cause of death sharpened suspicions once again. One spokesman said it had been a heart attack or fluid in the lungs; another cited a blood clot that had traveled from her leg to her heart— certainly plausible, since she had been treated by doctors for phlebitis. And several news reports mentioned the likelihood of a barbiturate overdose.

Christina Onassis suspected murder and pressed for an autopsy. The report released by the public prosecutor's office confirmed death from edema of the lung (the same thing that would cause Christina's death fourteen years later). Even though she was known to take sleeping pills and other sedatives, there was no report on barbiturate levels in Tina's blood. This oversight raised suspicions among many of her friends, who theorized that she fatally—and possibly accidentally— combined alcohol and pills.

Anne-Marie d'Estainville had a rare glimpse of what Niarchos himself thought when she went to lunch at Chanaleilles a week after Tina's death. "All Stavros wanted to do was talk about Tina," she recalled. "He was completely undone. He kept saying, 'Why did she have to do it?' He didn't cry, but it was as close as anyone could come to crying without tears."

Several months afterward, Niarchos still seemed in a peculiar state. A friend from New York went aboard the Atlantis, and Niarchos startled him by saying, "You were such a friend of Tina. I want to show you her cabin." He unlocked the door and said, "Nobody comes in here." There was Tina's nightgown thrown over the chair, and her hairbrush on the dressing table, just as she had left them.

Whether or not Tina had intended to take her life, the spotlight once again turned on Niarchos as a source of her deepening misery. "Maybe she died of pulmonary edema," says one British socialite, "but it was brought on by acute unhappiness." Rosemarie Kanzler disputes that conclusion: "I think Stavros was very much in love with Tina, but he was still flirting for his ego. He was a womanizer, and what can we do about that? The mentality is, he has to have a change."

Niarchos did little to dispel the doubts when he issued a statement insensitively revealing a suicide attempt by Christina Onassis two months before Tina's death, implying that Christina, not he, had caused her mother's depression. Equally troubling was his attempt to keep Tina's entire fortune, which Christina prevented. After a legal battle, Christina got $64 million and Niarchos settled for $9 million— plus one ship.

It didn't take long for European society to begin buzzing about prospects for a sixth Mrs. Niarchos. By December, Helene d'Estainville was seen in his company in Saint-Moritz, prompting tabloid descriptions of her as "an elegant woman in her late thirties" who was a "stylish performer on the ski slopes." There was such a flurry over his attentiveness toward Princess Maria Gabriella of Savoy, some thirty years his junior, that Niarchos issued a statement saying they were only ''excellent friends. ''

Another princess, Firyal of Jordan, the ex-wife of King Hussein's brother Mohammed, came closer than anyone else to winning the prize. Their first affair began when she was thirty-one and he was sixtyseven, and it lasted five years. Like Scheherazade, she captivated him with her Oriental glamour and her lively intelligence. She was the first woman to operate in his league, with a temperament as tough as his. A wise member of the Parisian "gratin'' explains, "He was scared of Firyal. All the other girls, they let him treat them badly. Firyal would answer back very roughly herself, and he was quite impressed."

The highborn women in the Niarchos coterie were displeased that Firyal could control him so thoroughly. They saw an opening when Firyal traveled to Houston on the Niarchos plane to care for one of her sons, who had been in an accident. A well-known baroness began whispering to Niarchos that Firyal was interested only in his fortune, that he needed a woman closer to his age who had money of her own. "Why not have a romance with Hel&ne Rochas? She is pretty, and she won't cost you."

But the match misfired. There was the small problem of communication: she had never bothered to learn much English, and he spoke little French. Her idea of perfection was breakfast in bed followed by dress fittings, art shows, and long gossipy talks on the phone with her friends. Life with Helene was just too tame and settled for Niarchos's taste. When friends saw how bored they looked at parties, it was evident that she couldn't possibly hold his interest.

Although he returned to Firyal for a time, her defiance eventually wore thin. The other women may have been too dull, but Firyal pushed him too far. "She was too much of a hellcat," says Marina Cicogna. ''He really cared for her, and she amused him, but he thought she was bad for his health—too much of a strain. It's sad, because nothing amuses him now."

For several years, Niarchos found comfort with a woman who devoted herself to him, Marina Palma, a wealthy Sicilian some forty years his junior. ' 'Greeks are very close to Sicilians," she told me. "We have a lot of Greek blood. We are just as tormented." Marina cared for him after he seriously injured his eye several years ago. But mostly she was an attentive companion, willing to stay with him as he retreated from the world.

For all her devotion, Niarchos pushed Marina Palma away with unreasonable demands such as having plastic surgery on her distinctive aquiline nose, which, according to Nigel Dempster, she refused to do. The paradox in Niarchos's view of women is all too evident: if a woman is agreeable and intelligent, he won't trust her, and if she is spoiled and difficult, he may be amused but he won't last with her. Still, both Marina Palma and Princess Firyal have stayed on friendly terms with him. Firyal visited him on Spetsapoula last summer, and earlier this year Marina Palma stood as godmother to the second child of Spyros Niarchos.

The deaths of Eugenie and Tina marked Stavros Niarchos forever. "He saw who his friends were, and who were not," says Peter Payne. "Since then he has resumed his position in the world, although more reclusive. He doesn't talk about Tina and Eugenie. Somehow it doesn't come up."

It certainly comes up everywhere else. One story, in the words of a Parisian aristocrat, "made a tour of the town" at Niarchos's expense. It concerned Eric Nielsen, a jet-set playboy who died several years ago. During his long illness, he was said to have encountered Niarchos in Paris. "Eric, you're not dead yet," Niarchos supposedly said. "No, because I didn't marry you, Niarchos" was Nielsen's reply.

None have been more deeply affected than the four Niarchos children who lost their mother and their aunt at such an early age. Niarchos bothered little with his children when they were young. As they grew up, he intimidated them. "He loves his children, but to him they are idiots," a well-connected Greek man explained to me. "If one would say something he doesn't like, he would be very rude and insulting, doing what an educated person would not do. But that is a Greek attitude. Greeks are tough with their kids. It is not uncommon. Now he is softer on them, but they have to be with him all the time."

Philip and Spyros were schooled at fashionable Le Rosey, and Spyros put in two years at Gordonstoun before joining his brother at Atlantic College in Wales. Spyros also studied economics at the University of London and did a training stint at Citibank in New York. By the time they were twenty, both boys were at work in Niarchos enterprises. At night they hopped the nightclubs—Castel's in Paris, Xenon in New York with the Warhol crowd, King's Club in Saint-Moritz. Their names were linked with models, actresses, and heiresses. Nicaraguan actress Barbara Carrera distinguished herself by having short flings with both young men.

Philip settled down by marrying an obviously pregnant Victoria Guinness in a quiet civil service in Paris in 1984. Niarchos did not attend the wedding, although he later warmed to the marriage when they named their first child after him. In top hat and tails, Spyros married Daphne Guinness, the sweet-natured daughter of Lord Moyne, three years later in a small ceremony at a Greek Orthodox church in Paris. Daphne's grandmother is Diana, Lady Mosley, one of the famous Mitford sisters, who was jailed during World War II for her Nazi sympathies.

The strong social connections brought by each marriage pleased Niarchos. Tall and blonde, Victoria is the more stylish and imposing of the two wives, with wavy Pre-Raphaelite hair and regal bearing. She has become the chatelaine for her fatherin-law, overseeing his households as well as her own.

When I ask Philip what he feels is the most important lesson he has learned from his father, he says instantly, "The value of family." Spyros nods affirmatively. Their tight family arrangement may seem oppressive to outsiders, adds Philip, but it comes naturally, as does the family's premium on privacy. "A lot of people are envious," says Philip, "but the way it is arranged works very well for all of us. My father went through a lot of troubles and tragedies, and he took care of us. Now it is our turn to care for him."

Still, friends say that when the brothers are tethered too tightly they long for diverting guests. Last summer Niarchos gave a small dinner party on Spetsapoula—one of the few times in recent years when outsiders have been invited to his table. The late Italian film producer Franco Rossellini spent the evening regaling the table with gossip and anecdotes. At the end, Philip Niarchos told him, "I am so grateful. You made me see my father laughing again."

Constantine remains a persistent worry for his father. He works in the London office on the shipping business and tries to be punctual for his father's afternoon phone calls, but he is still a rakehell, even after spending time in the Betty Ford Center in California. His most notorious scrape was in the early hours of Christmas Day in 1984, when he forced his way into the Aga Khan's Saint-Moritz hotel suite and wakened him by shouting and throwing money at him. Constantine accused the Muslim spiritual leader of having designs on Pilar Goess, an Austrian model who had broken with Spyros Niarchos several months earlier after meeting the Aga on Spetsapoula. The incident caused an irreparable rift between Niarchos and the Aga Khan.

Constantine went on to marry Princess Alessandra Borghese, a strong-willed Italian aristocrat who worked as a stockbroker. At first, friends thought she would keep him in line, although Stavros and the two brothers disapproved of her. "She was told to stay on the right side of Stavros, and she ignored that advice," says one Italian woman. The marriage foundered after less than a year, amid accusations that he flew into "violent rages." When she sought a multimillion-dollar settlement, the Niarchos family branded her a gold digger, although she donated her award of $120,000 to charity.

As the sole female in an overwhelmingly male-dominated family, Maria Niarchos rebelled by choosing the company of men unsuitable to her father. When she decided to marry Alix Chevassus, a handsome Parisian boulevardier, Niarchos cut off contact with her for months. Eventually he relented and gave his twenty-yearold daughter a $500,000 wedding on the grounds of Douville Manor, his seventeenth-century home near Lisieux, Normandy, in June 1979.

Niarchos installed more than six hundred guests—an array of European aristocrats and celebrities including Princess Caroline of Monaco, Ringo Starr, and Rudolf Nureyev—in Deauville's three top hotels, oddly stipulating that they pay for their phone calls. Under a Mylar tent, tables were constructed around apple trees covered with silk blossoms. The guests drank champagne, dined on caviar, pheasant, pigeon, and salmon, danced at a Xenon-type disco in the bam with a neon sign flashing the couple's initials, and watched a fireworks display. Maria wore a diamond necklace that had belonged to Marie Antoinette, a gift from her father, who announced, "I only have one daughter, and she will only marry once, so I want to do it right"—a remark that must have stung the forgotten Elena.

Maria's marriage lasted only slightly longer than Constantine's. She bounced back by taking over her father's bloodstock business, and last year she married quiet, hardworking Stephan Gouaze, who works for a French bank in Djakarta, where they live in a tasteful but unimposing four-bedroom house. ''She has more independence now," says one of her friends. ''As a woman, it is expected that she follow her husband. But in her case that gives her a privileged position."

How the children will eventually run the family empire is anybody's guess. Only Maria found a chance to show her mettle, when her father lost interest in his horses, but at the family's insistence she has been selling off their bloodstock instead of buying. Since she is a woman, she is unlikely to assume a significant role.

Friends say that Philip and Spyros will dominate. As the eldest, Philip clearly takes the lead. He has been bitten by his. father's art-collecting bug, although his focus is exclusively on contemporary artists such as Julian Schnabel and Francesco Clemente, both of whom he has made a point of getting to know personally. Philip and Spyros seem close and comfortable, one often picking up on the other's thoughts to respond seamlessly to my inquiries. But after years of doing their father's bidding, the sons remain untested. As one of their Greek friends explained, Niarchos "has never given them the freedom to really find out what they can do."

The most remarkable aspect of Niarchos's waning years is that the obsessive drive that built his fortune and his great art collections is now directed entirely on himself as he doggedly follows diet and exercise routines to maintain his health. Yet in his quest for survival he seems to have given up on life.

When his two newest grandchildren were christened in February in the large pine-paneled foyer at Villa Marguns, he left after a short time and declined to join the celebratory dinner later that evening at the Chesa Veglia restaurant. Even old friends such as Gianni Agnelli catch only fleeting glimpses of him. "Doesn't he miss seeing people?" I ask Philip. "Yes, he misses them," Philip replies, "but he knows it would be too much of a strain."

The grand life of Stavros Niarchos, which once approached the scale of opera, has become small and prosaic. "He gives the impression that he can't give a damn, but basically he cares a lot about what people think," says Peter Payne. "What he appreciates is not being treated as if he were a monster in a glass cage." Yet that is what he has become. The price for controlling his own world is that Stavros Niarchos is the only one who can live there.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now