Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

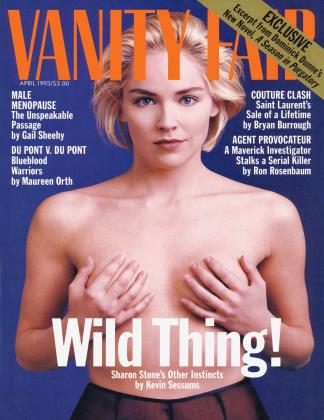

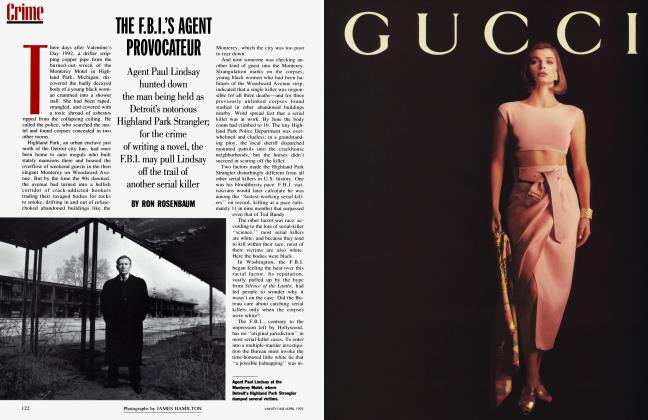

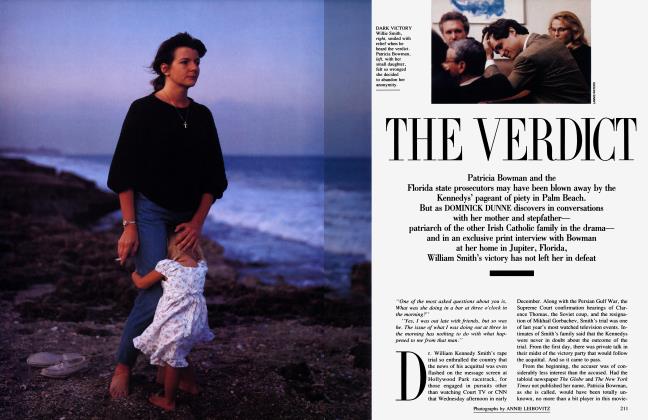

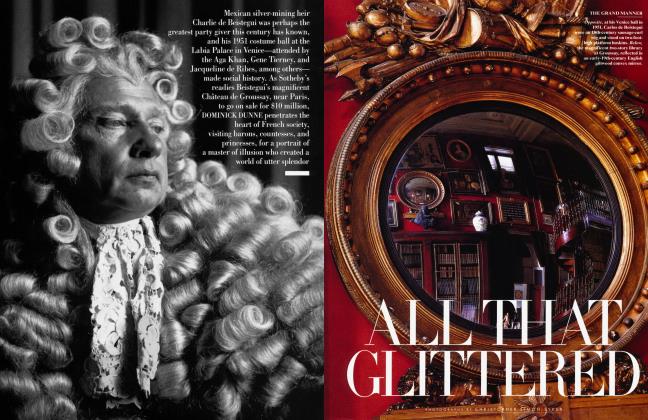

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA young girl is killed by the scion of a wealthy East Coast, Irish Catholic family. In an exclusive excerpt from his new novel, A Season in Purgatory, DOMINICK DUNNE explores crime, cover-up, and guilt in the world of power and privilege

April 1993 Dominick Dunne RiskoA young girl is killed by the scion of a wealthy East Coast, Irish Catholic family. In an exclusive excerpt from his new novel, A Season in Purgatory, DOMINICK DUNNE explores crime, cover-up, and guilt in the world of power and privilege

April 1993 Dominick Dunne RiskoConstant Bradley, my best friend at Milford Academy, was a spectacular young man in every way. He seemed almost too good to be true. His name, his looks, his trim six-foot-two athletic frame, strained reality. He possessed a refinement of face that his parents did not have, and his vocal pattern was less strident than that of his parents and older siblings. His bearing, wit, and style caused much comment, especially among the young ladies at the various boarding schools in Connecticut and Massachusetts who had heard of the handsome young heir to the Bradley fortune. He had a facility for sports, especially the kind thought of as gentlemen's sports: tennis, golf, squash, lacrosse, and sailing. In spite of the fact that his family's wealth was of only two generations' standing, he had acquired all the outward manifestations of privilege and bore them with the not unattractive arrogance of a patrician. Perhaps, behind his splendid looks, there was a hint of menace, but I would not have seen it then, and if I had, I would have thought it an enhancement. All the daughters of the Protestant families who abhorred the Irish Catholic Bradleys were mad about Constant. His blond good looks left debutantes across the ballrooms of every country club where he danced gasping with desire, especially Louise Somerset, Leverett Somerset's daughter, who was called Weegie. Any one of them would have defied her family if Constant had been inclined toward her, but Constant, even then, was attracted to the forbidden fruit, and the forbidden fruit was Weegie Somerset, who was to be, in two years' time, the prettiest debutante of her season and the social catch of the city.

They fascinated each other from the time they met in Mrs. Winship's dancing classes, when they were 13. He went to her school for her dances, and she went to his school for his. He was asked to her parties at her house, to which his family had never been asked and where the only things Irish or Catholic were the maids, in their black silk uniforms and starched white caps and aprons, who beamed at him in approval, knowing that he was the son of Gerald and Grace Bradley.

My friendship with Constant was a surprise to me. I was one of the unspectacular members of our class at Milford, one of the quiet ones, even though I was the possessor of an unusual sort of celebrity. I remained aloof from the rest of the boys, although, in truth, my aloofness was merely an act of self-defense; I longed to be one of them. Constant played bridge very well, which made him a great favorite of Mr. Fanning, the French teacher, who wore beautiful tweed jackets and entertained the bridge-playing group in his rooms each night after dinner and before study hall. I was not part of that set. I disliked Mr. Fanning, who seemed to cater to all the rich boys.

One night Mr. Fanning came to me in study hall. "Harrison," he said, "the headmaster wants to see you in his office. Immediately."

There, in Dr. Shugrue's office, where I had been only once before, when my father entered me in Milford, I was told that my mother and father had been murdered. I did not cry, although I sank into a chair in front of his desk while he told me the facts of the horrible event.

By the time I returned to study hall to pick up my books and papers, word had gone round of my shocking news. Everyone stared at me. In silence, Constant Bradley solicitously helped me gather up my things. The next morning Aunt Gert came to take me home. Leaving the school, aware that the boys were watching out of the windows, I wished that she had brought my father's Oldsmobile, black with whitewall tires, rather than her Chevrolet, four years old and badly in need of a wash.

After Detective Stein, who was investigating the case, visited me at school one day, to report only that there were no leads in the double murder, Constant sought me out. The celebrity of the case never really exceeded the limits of the city in which it had occurred, but everyone at Milford knew, and Dr. Shugrue had exhorted the boys not to question me on my return, an exhortation ignored by Constant. At first, his interest in me was no more than blunt curiosity. He asked me the kinds of questions no one else, for propriety's sake, dared to ask. If they had come from anyone other than Constant, I would have ignored the questions, or walked away, but I was entranced with his attention, and replied, discovering I was eager to have a friend in whom to confide. When he asked me to sneak into the village one afternoon, which was forbidden, to go to a film he wanted to see, I was thrilled to be his accomplice, although I was the type who never broke the rules. Soon we became inseparable, and in time I met his parents and all his brothers and sisters. Constant had the most elaborate and expensive stereo equipment in the school, and each week all the latest cassettes arrived from a record store in New York. He knew the lyrics to every James Taylor song. We smoked pot and drank beer, risking expulsion. For me, it was thrilling. I didn't mind telling him the answers to test questions; I took it as an honor. Sometimes, between confession on Saturday afternoon and Communion on Sunday morning, he succumbed to powerful sexual urges and masturbated. "I beat my meat," he would say to me. In those days he beat his meat a great deal, especially after each new issue of Playboy came out. Occasionally, not always, I accompanied him in the masturbation experience, and such acts were certainly not uncommon to boys in boarding school, but my eyes were on him, not on Playboy. The next morning, fearing the headmaster's wrath if he did not go to Communion, Constant more than once paraded up the center aisle to the Communion rail, where, fearing also God's wrath, with its attendant promises of eternal damnation and the pains of hell if he received the Blessed Sacrament while in a state of mortal sin, he became lost in the crowd of communicants, and then returned to his pew, head bowed in pious post-Communion prayer, without having received the Sacrament, although no one but me was aware of his ruse.

"Do you mind dancing with a man with an erection?" Constant asked Winifred Utley.

There was someone named Diego Suarez in our class, a rich South American boy, the son of a fashionable diplomat Washington, whom everyone, for obvious reasons, called Fruity. He pretended not to mind the name. A louse, a gossip, an unpopular fellow, he was the single exotic in our youthful Catholic midst. When autumn began to turn cold, he wore his topcoat over his shoulders in a flamboyant manner, the sleeves dangling at his sides or swirling around him when he turned abruptly to address somebody. It was a style made famous by the Duke of Windsor, he told us, who had been a great great friend of his grandfather's in Palm Beach, although few of us knew then who the Duke of Windsor was. Fruity had spent a summer in Beverly Hills and told lesbian stories about movie stars with great authority, which shocked, disappointed, or titillated his teenage audience. "Oh, yes, it's absolutely true," he told us. "Everyone in Hollywood knows about the two of them. It's a notorious affair."

It was he who started the rumor that I was transfixed by Constant Bradley. "I can see the famous Bradley charisma has transfixed you, Harrison," he said one day on our way to study hall in his loud, affected voice for all to hear. "You cannot keep your eyes off him."

I blushed. For a while, everyone in the school talked about it. Constant, untroubled, roared with laughter at the story, while I suffered in silence.

Transfixed. What an odd word. Was I transfixed by Constant Bradley? Yes, I was. Completely transfixed.

Halfway through our junior year, Constant was expelled after being caught in possession of magazines full of pictures of women engaged in sexual acts. To get him back into the school, Gerald Bradley persuaded Cardinal Sullivan to visit Dr. Shugrue and offer Milford a science building or a new library. Dr. Shugrue accepted the library, but there was one stipulation. A paper had to be written by Constant, 5,000 words on morality, before he could be reinstated. While the family went to a seaside cottage in Rhode Island, Constant was to stay behind and write his paper. I returned to Ansonia. A friend of my father's got me a summer job on The Hartford Courant. In the event that there might not be enough money for me to go back to Milford for my sixth-form year, I registered at a public high school. In late July I received a telephone call at my aunt's apartment from Gerald Bradley.

"Hello, Harrison.''

"Hello, Mr. Bradley." I had never talked to him on the telephone before. As always, he made me nervous.

"My son needs to write a paper before the headmaster will reinstate him into Milford. Are you aware of that?"

"Yes, sir. I thought he wrote it."

"Have you read it?"

"Yes, sir. He sent it to me."

"Not good, is it?"

"I don't know."

"Not good enough, that's for sure. Constant doesn't have a way with words the way you do. I have a plan."

"Yes?"

"I'd like you to write the paper for Constant."

"Me?"

"You want to be a writer, right?"

"Yes."

"Here's a chance to see how good you are."

"But, uh, if Dr. Shugrue should find out?"

"He won't. It'll be our little secret."

There was a moment of silence.

"You might wonder what you get out of this?"

"Oh, no, sir. I'll be happy to do it."

"You must never say that, Harry. You must always put a price on everything. That's what business is all about."

"I couldn't take money, sir."

"A supporter must be rewarded for his support, Harrison," said Gerald. "Are you aware that your father's estate is considerably less than what people imagined it was going to be?"

"Yes, sir." I wondered how he knew such a thing. It was information I had not even told Constant.

"Are you aware that there might not be enough money to send you back to Milford for your senior year?"

"Yes, sir."

"And you would like to go back, would you not?"

"Yes, sir."

"Consider it done. Your tuition paid for, that is. Providing, of course, that your report meets with Dr. Shugrue's approval and Constant is reinstated."

"Yes, sir."

"No one must know, of course. None of the others in the family."

"Yes, sir."

"Just you and me. And Constant, of course. The tuition money will be paid to your aunt. And she will in turn pay the school. That way, there will be no connection in the headmaster's mind."

"I understand. But what will my aunt think? She has different ideas."

"Your aunt is apparently very fond of the Maryknoll Fathers. Missionaries. Good works. In foreign places. I am prepared to make a large donation through her to the worthy fathers. Believe me, Harry, I have been around longer than you. It will be an irresistible offer."

"Why?" I asked.

"Because I have great hopes for my son, Harry. I believe he has the makings of greatness in him. When he has outgrown his boyish pranks, that is."

For two weeks I worked on Constant's paper, while keeping my daytime job on The Hartford Courant. I had never worked so hard on anything. I wanted to do it for Constant, but I also wanted to do it for Gerald Bradley. I saw my future as being in his hands, as if he might do for me, when the time came, what my own father could never have done.

I found that in writing in another person's name, as if I were Constant Bradley, I possessed a courage that I did not ordinarily possess when writing in my own name. All my timidity vanished. My dead father had found me flawed and imperfect, and I had accepted his judgment, but writing as Constant I became sure of myself, and experienced true joy in the writing process. I wrote about Constant's grandfather as if he were mine. And his father and mother. I wrote about being a member of a large Catholic family. I stressed the importance of family, something I had never felt in my own life. I wrote about the obligation of the wealthy to help others who were less fortunate. I wrote about the significance of early education, particularly an education at Milford, in preparing Catholic boys to enter the Ivy League colleges and to carry with them the Catholic values learned at school. I wrote about leadership. I wrote about a future in public life that would embody the values that I had learned at Milford. All these things would have sounded preposterous coming from my lips, but not from the lips of Constant Bradley.

I mailed the 20 double-spaced typed pages to Gerald Bradley at an office he kept in New York. As per his instructions, there was no covering letter. I waited, but heard nothing in reply. A week went by. Then two. Finally there was a telephone call for me at my aunt's house. It was Gerald. He invited me to come and spend the Labor Day weekend at the seashore in Rhode Island. He said the whole family would be there. There was to be a celebratory dinner in honor of Constant. I waited for him to say something about the paper I had written, but he said nothing.

"What is the reason for Constant's celebration?" I asked.

"He is returning to Milford," replied Gerald. "The cardinal has arranged everything."

I spent other weekends after that with the Bradleys. I was in Scarborough Hill with them over the following Easter vacation. On Sunday, Jerry, Constant's oldest brother, suggested a game of softball. Before a car accident, he had been the best athlete in the family, and he still enjoyed games, even though he could no longer play. In the family, there was never any hesitation when games were suggested. They all loved to play, both the boys and the girls. Sides were chosen.

"I'll ump," said Jerry.

"Be careful of my daffodils," called out Grace Bradley, Constant's mother.

"Who has the bat?"

"Everything's in the mudroom. Bat, balls, gloves," said Fatty Malloy, a poor cousin of the Bradleys'. Fatty always knew where everything was in the Bradleys' house. The mudroom was stocked for all sporting occasions, enough for family and guests. There were tennis rackets, and golf clubs, and riding hats and crops, and croquet sets, and swimming-pool gear, and gloves and softballs and bats.

"I'll get very angry if my daffodils are trampled, ' ' said Grace.

"Oh, Mother,'' said Kitt and Mary Pat.

I hated to play with them. They were all too good. And they were merciless if you missed a ball or, God forbid, struck out.

"That was your fault, Harrison,'' called out Jerry. "You let that ball go right through your legs."

"Sorry," I called back.

"Hit it to Harrison," yelled out Sandro when Kitt was at bat, meaning that I would be sure to miss it.

She did. She hit it hard, straight out to second base. I caught it. I threw it to Constant on first. She was out. Cheers from Constant and Mary Pat.

"You would have to catch it the one time I'm up," said Kitt.

"Sorry," I said.

"You can't be sorry about everything," she said.

Constant was the star of the afternoon, of course. He hit a homer with Fatty and Mary Pat on base. He loped around the bases joyously, savoring his moment. At home plate, he picked up the bat and swung it over his head. "And I did it with a cracked bat," he said. Then, with both hands, he sent the bat flying high into the trees and over onto the wooded area of the Somerset property. Kitt and I ran to retrieve it, but we couldn't find it. The wooded growth between the two estates was heavy and dark.

"What's the big deal? There's about 10 more bats in the mudroom. Get another one, Fatty," said Jerry.

Then Gerald called down from the terrace, "The Wadsworths are complaining that you're making too much noise and spoiling their Easter-egg hunt."

"Screw the Wadsworths," said Jerry.

There were cheers and roars of laughter.

Soon the family made their way back across the lawn, past the tennis court and the pool, up to the terrace of the house. It was time for Sandro to leave for Washington. Already the family referred to him as the Congressman. Charlie, the chauffeur, was standing by to drive him to the airport. Constant's sister Maureen and her fiance, Freddy Tierney, were flying to Chicago to spend time with Freddy's family. Desmond, the third of Constant's brothers, was on duty at the hospital. Farewells were being said.

Through the woods a young girl appeared.

"Hi," she called out. Only Constant and I were still near the softball area, collecting gloves.

"Hi yourself," said Constant.

"Now, don't blame me for this, I'm only the messenger, but the Wadsworths sent me over to ask you to quiet down a little," she said.

"We're spoiling their Easter-egg hunt. We already got the message by telephone. Look, we even stopped playing."

"Well, that's my chore completed." She turned to go.

"What's your name?" asked Constant.

"Winifred Utley."

"Winifred Utley." He repeated her name. ' 'I've never met a Winifred before."

"Indirectly you have."

"How?"

"My name means nothing to you?"

"You have a very pretty face, Miss Winifred, but your name means nothing to me."

"I know who you are. All the girls at my school know who you are. You're famous. My mother once picked you up when you were hitchhiking and drove you home from Milford," said Winifred.

"Oh my God, of course," said Constant. "I got kicked out of Milford right after that."

"But I thought you were graduating from there in June."

"I am. My father is giving a new library, and I got back in. It's how bad rich kids get through life."

"I think you're a big tease, Constant."

"I think you're adorable, Winifred." He looked into her fresh, lively face, the face of a 15-year-old, a face that depended for its prettiness on her youth. It would probably never be so pretty as right then. "What are you doing here?"

"I just told you. The Wadsworths sent me over."

"I meant, what are you doing here in the city?"

"We've moved here. My father is the new president of Veblen Aircraft."

"Where do you live?"

"Right near you. We're on Varden Lane, behind the Somersets' house."

"I know that house. The Prindevilles used to live there."

"That's it."

"There's a shortcut behind our tennis court."

"I know."

"Perhaps a midnight rendezvous is in order."

"On the shortcut, you mean?"

"Yes."

She giggled. "Not likely. I've heard of your reputation."

"From whom?"

"All the girls at school talk about Constant Bradley."

"Good or bad?"

"Depends on who's doing the talking." She giggled again and ran off through the woods the way she had come.

Two nights later Constant, Mary Pat, Kitt, and I had dinner at the Country Club. It was the girls' last night before they returned to school at the Sacred Heart Convent. Grace and Jerry were attending a political fund-raiser in the downtown part of the city. Gerald had gone to New York "on business," as Constant always said with a wink when he thought his father was with one of his lady friends.

"He's got a new one. Eloise Brazen," he said.

"Certainly your father didn't tell you that," I said.

"No. Fuselli did." Johnny Fuselli, I knew from Constant, was a former racketeer who worked for Gerald Bradley.

Most of the talk at dinner was about Maureen's wedding. It was to be the first time that Mary Pat and Kitt would be bridesmaids.

Constant was in a good mood, entertaining his sisters, even joking with the waitress, who refused to serve him wine because he was under-age.

"My father lets me have wine at home, Ursula," he said. Constant always remembered the names of the help.

"Then you better go home to your father," she replied.

"Oh, these provincial places," said Constant.

"He's only teasing you," Kitt said to the waitress. "He's a big tease. He knows perfectly well he can't have wine at the club."

There was an elaborate clearing of the throat from Mary Pat. "Oh, oh," she said ominously.

"What?" asked Constant.

''Check out the door to the dining room. ''

The Somersets were arriving with their daughter. I knew that Weegie was not speaking to Constant, because he had gotten rough with her a week earlier when she wouldn't "makeout." Mr. Carmody, who seated the members, led the family to a table next to ours, but midway across the dining room Leverett Somerset, without halting Mr. Carmody, changed direction and guided his wife and Weegie toward an empty table at the opposite end of the room.

"Sit here, Weegie," he said. He seated his daughter with her back to our table.

"Well, at least we're almost finished," said Kitt.

Constant excused himself from the table. "Be right back," he said. He walked out of the dining room and turned right toward the men's locker room. Beyond the locker room was a men's bar for drinks after tennis and golf. The bartender, Corky, was just closing up.

"Hi, Corky," said Constant.

"Mr. Bradley," he replied.

"Can you give me a drink, Corky?"

"You know I can't serve anybody under 18."

"Yeah, I know, but there's nobody around."

"Club rules. State law."

"Yeah, I know." He placed a $10 bill on the bar. "Have you seen my cousin Fatty Malloy?"

"I saw him at Father Curry's wake last week."

Constant placed a second $10 bill on the bar and pushed the money toward the bartender. "Come on, Corky. Scotch."

"Vodka. It looks like water, ' ' said Corky.

"Pour in a little more."

"Take it in the locker room. Don't drink it in here. I need this job."

When Constant returned to the table 10 minutes later, I could tell he had been drinking. He did not look in the direction of the Somersets' table. From another room came the sound of dance music.

"What's the music?" Constant asked the waitress.

"There's a junior club dance in the lounge," answered Ursula.

"How come you aren't there, girls?" he asked his sisters.

"No dates, and besides, I'd rather be having dinner with you sixth-formers," said Kitt. "Much better than dancing cheek to cheek with those pimply faces, like Billy Wadsworth."

After dinner, we made an elaborate exit, led by Constant and Kitt, walking through the lounge straight across the dance floor to the hallway. Several girls stared at Constant. One girl stopped in the middle of a dance with Billy Wadsworth and said, "Hi, Constant."

"Oh, hi, Winifred," said Constant. "Do you know my sisters, Mary Pat and Kitt? You know Harry. This is Winifred Utley. She's new in town."

"I saw you in the dining room. I was hoping you'd come in, even though this group is too young for you," said Winifred, walking away from Billy.

"We're just passing through on our way out," said Constant. "We're not dressed for the occasion."

"You wouldn't stay for just one dance? Imagine how popular I'll be back at school if I can say I've danced with Constant Bradley," said Winifred.

"That's entirely up to my sisters," said Constant.

"Oh, please tell him it's all right," said Winifred. "Just one dance. Everyone says he's such a wonderful dancer. The dance is over at 10, and I have to be home by 10:30. I have the strictest mother ever."

Calmly, he wiped his fingerprints off the head of the bat with the tail of his white Brooks Brothers shirt.

"We'll stay here with Harry," said Kitt.

Constant led Winifred to the dance floor. "Do you mind dancing with a man with an erection?" he asked.

"You're a naughty boy, Constant Bradley. Cute, but naughty," said Winifred.

"Did Bradley say what I thought he said?" asked Billy Wadsworth, scowling.

We watched the dancers for a while. Constant, older than the other boys by a year or two, was the only one on the floor not in black-tie, but he and Winifred dominated the young group, causing others to stare at them. Then he disappeared in the direction of the men's locker room again. After several numbers, he came over to where I was standing. "Why don't you take the car and drive the girls home. I'm going to stay and dance with Winifred for a bit."

"Billy Wadsworth doesn't appreciate you, Constant," said Kitt. "He's the one who brought her."

"He'll get over it," replied Constant.

"Do you want me to come back for you?" I asked.

"If you want."

"Good old Constant. He always dumps us," said Kitt.

The telephone rang in the Bradley house. Grace Bradley, who was a light sleeper, switched on the reading light inside the canopy of her bed and looked at her bedside clock. It was two o'clock in the morning. Late-night calls always alarmed her. She thought of Gerald in New York on business. She thought of Sandro in Washington. She thought of Maureen in Chicago with Freddy.

"Hello?" she said, at the same time making the sign of the cross.

"Mrs. Bradley? This is Luanne Utley. I'm terribly sorry to bother you at this hour. I'm looking for my daughter, Winifred. She was supposed to be home at 10:30. My husband is away on business, and I'm out of my mind."

"Who is this?" asked Grace, confused.

"Luanne Utley. Mrs. Raymond Utley. My husband is the new president of Veblen Aircraft. We bought the Prindeville house on Varden Lane."

"Yes? Isn't it awfully late to be calling?"

"I'm looking for my daughter, Winifred."

"Why would you think she'd be here? It's two o'clock in the morning. Do my children even know her?"

"Your son Constant danced with her at the club junior dance tonight."

"I don't think my son was at a dance, Mrs. Utley. I think he had dinner with his sisters."

"Please. Would you look, Mrs. Bradley? I'm sorry to bother you. I know it's a terrible hour to call anyone. Winifred said she'd be home at 10:30. She's never late. Ever. I am worried about her. Could you put your son on the phone? Please."

"Hold on," said Grace. She got out of bed and put on her robe and slippers.

The room that I usually used in that house, the room that had once been Constant's sister Agnes's room, before she was put away, had lately been used by Freddy Tierney, and I was sharing a room with Constant. I was in that room asleep when Grace opened the door and turned on the light. Immediately I awoke and sat up in bed.

"What's the matter?" I asked, startled to see her standing in the doorway.

"Where's Constant?" she asked.

I looked over to his bed. It had not been slept in. "I don't know," I said.

"There is a woman on the telephone. Mrs. Utley. She is looking for her daughter. She said that Constant was dancing with her at the club. Do you know if that's right?"

''Yes, he did dance with her."

''Are Kitt and Mary Pat here?"

"Yes, I brought them home. Constant stayed. I went back to pick him up when the dance was over at 10. But he wasn't there."

"And the Utley girl. I can't remember her name. Was she there?"

"Winifred. I assumed she went home with Billy Wadsworth. He was her date."

Grace went to an extension phone in the upstairs hall and picked it up. I got out of bed and followed. "No, Mrs. Utley. Your daughter is not here.. .Yes, he is, but he is asleep."

Grace looked at me for an instant as she told her lie.

"He said your daughter went home with Billy Wadsworth.. .Oh, I see. You've talked to Mrs. Wadsworth and to Billy... I wish I could help you, Mrs. Utley.. .Oh, no, I wouldn't call the police," said Grace quickly. "You can't be in a safer neighborhood than this. It's patrolled hourly. Maybe she slept over with a girlfriend from school. I'm sure it will be all right."

She said a few more comforting things. Then she hung up. She looked at me again. There was an expression of enormous sadness on her face, a look I had never seen before. "Girls, girls, girls," she said. "Constant's just like his father. And his brothers."

I didn't reply. I didn't know what to say.

"How old is this Utley girl?"

"Fifteen, I would think."

"Fifteen. Imagine her being out at this hour. I may not have any control over the men in my life, but I most certainly do over my daughters. Will you go downstairs? If Constant is there with her, drive her home, will you? Varden Lane. Tell the silly girl her poor mother is frantic. Good night, Harrison."

I watched her walk down the long hall to her bedroom. I had always thought she didn't know of her husband's infidelities. I realized then that she chose to ignore them. At her bedroom door, she turned back to me and saw me watching her. "Don't tell Mary Pat and Kitt about this. I don't want my daughters to know such things go on in this house."

I looked out the window. Constant's Porsche was in front of the garage, where I had parked it. I quickly pulled on my trousers and a sweater and a pair of loafers. I went down the hallway as quietly as possible and down the stairway. At the entrance to the living room, I cleared my throat loudly, to warn them if they were in the act of making love. There was no reply. The room was quite dark and silent, except for the loud ticking of an antique clock on the mantel. I switched on the lights. The room was empty. I turned and walked over to the library. The door was shut. I knocked. I loudly cleared my throat again. There was no reply. I opened the door and walked in. "Constant?" I whispered. I turned on the lights. There was no one there. I turned on the lights in the dining room. It was empty. And in the lavatory under the curved stairs in the main hall. Empty. Then I turned on the lights in the small room off the main hallway which Gerald used as an office. It, too, was empty.

Suddenly, there was a tap on the window. Someone was standing outside. I froze in fear. My parents, whom I rarely thought of, flashed through my mind, how it must have been for them at that moment when their attacker was upon them. The window was of Tudor design with small diamond-shaped panes. With the lights on in the room, it was difficult to see out. There was another tap, more urgent.

"Harry, Harry," the person said in a loud whisper. Standing outside the window was Constant.

I ran over to the window. It opened out. "Jesus Christ, you scared me," I said.

"Shhh," he whispered.

He looked slovenly, dirty—his shirt unfresh, tom, darkly stained, his trousers unpressed. His skin was pale. His hair was sweat-wet and slicked back. There was a sore on his lip.

"What the hell is the matter with you?" I whispered.

"Oh, Harry," he said. He was crying. "I need help."

I tiptoed through the hall to the kitchen. Bridey, the housekeeper, had the room next to the maids' dining room off the kitchen, and Bridey was known to be a light sleeper. The other maids, Colleen and Kate, slept up on the third floor. I continued to tiptoe until I got to the door. As quietly as I could, I unfastened the lock, the double bolt, and then the chain. Outside, Constant was standing by the door, breathing heavily.

"Why are all the lights on?" he asked.

"I turned them on. I was looking for you. Your mother sent me downstairs."

"Ma? Why?"

"Mrs. Utley called. Winifred's not home. She called the Wadsworths. Your mother thought you were with her downstairs in one of the rooms, but she didn't want Mrs. Utley to know that. I think Mrs. Utley is going to call the police."

"Oh my God. Shut off all the lights, Harry. Quick!"

Alarmed by the urgency in his voice, I went through the downstairs, turning out the lights in the living room, library, dining room, lavatory, and office. When I went back out the kitchen door, Constant was standing in the same place, as if he were in a trance.

"What's the matter?" I asked.

He turned and walked away toward the tennis court. I followed.

"You've got to help me, Harry. I need you. I need you like I've never needed anybody in my life. Are you my friend?"

"Sure I'm your friend. You're the best friend I ever had."

"No matter what?"

"No matter what."

"Follow me."

We went across the lawn, past the tennis court and pool, to the area at the bottom of the property where we had played softball on Easter Sunday. He continued walking into the woods. It was pitch-dark.

"Here," he said finally, stopping. "We have to move her deeper into the woods."

"Who?"

"Winifred. We have to move Winifred."

"Is she hurt?"

"She's dead."

I couldn't see his face in the dark.

"Dead?"

He dropped to his knees. There in front of him on the ground was Winifred Utley. She was wearing the same pink dress she had on at the dance at the club, but it was pushed up on her so that part of the skirt covered her face. Her panties were pulled down to her knees. I reached out to touch her, but her face and head were covered with blood. I recoiled. I realized that the stains on Constant's shirt were blood.

"Constant, what happened? Who did this to her?" I spoke in a whisper. My heart was thumping in my chest. I knew that a time of my life had come to an end. A door had shut. Nothing would ever be the same.

"Help me move her deeper into the woods, closer to her own house."

"Why move her? We have to go for help."

He ignored me. "I'll get her head. You get her feet."

"But why?"

"I have to get her off our property. If I drag her through the woods, they'll be able to tell. Get her feet."

As we started to lift her, she let out a faint moan.

"Constant, she's not dead." I was joyous. We placed her down on the ground again. "I'll go for help."

"No you won't. She's beyond help. She's more dead than alive.''

Then he picked up part of a baseball bat, the bat from the softball game on Easter Sunday, the bat he had flung into the woods because it was cracked, the bat that neither Kitt nor I had been able to find. It was broken in two. The head of the bat was covered with blood.

I heard another sound from Winifred. Still staring at him, I knelt down to look at her. I could hear the gurgling sound of saliva in her mouth as she expired. I covered my own mouth to stifle the scream that was forming there. "She just died," I gasped. My voice was barely above a whisper, but, unmistakably, there was the beginning of panic in it.

When he spoke, his voice was harsh as he enunciated each word carefully. "You cannot panic, Harry. You cannot lose your head. Do you understand? We have to stay very, very calm. We have to do everything right. Tomorrow, when this is all over, we can fall apart, or mourn, or whatever has to be done, but not now. Do you hear me, Harry?"

I stared at him.

"Do you hear me, Harry?"

I nodded my head.

"Say the words, Harry. Say, 'I hear you, Constant.' Say, 'I will stay calm. I will not fall apart.' Say it."

"I hear you. I'll stay calm. I won't fall apart."

"Good. This has happened. We can't undo it. We have to deal with the situation as it is. Do you understand?"

"Yes."

"Take her feet."

Numbly, I followed his orders. I performed my assignments in mute stupefaction, distancing myself mentally from what my hands were doing. We lifted her up again, but this time I did not look at her. We moved deeper into the woods. Then, at a head signal from Constant, we moved in the direction of Varden Lane, which backed onto the Bradley and Somerset estates. When we were within sight of the three-story red brick Utley house, we saw that there were lights on on several floors. There, at a second signal from him, we laid her down behind a clump of bushes. He began covering her with leaves. Calmly, he wiped his fingerprints off the head of the bat with the tail of his white Brooks Brothers shirt.

"We better get back to the house. Don't talk on the way. I don't want to wake up Charlie in the chauffeur's apartment over the garage."

"What about Winifred? Do we just leave her?"

"Winifred? What about me? It's too late for her. I'm the one we have to think about. It was her fault. The whole thing was her fault."

We re-entered the house through the kitchen door. We stood in the dark for a moment to see if the house was quiet. He placed the head of the bat down on the counter.

"Get a garbage bag from under the sink," said Constant. He began to take his clothes off—shirt, trousers, undershorts— and piled them into the garbage bag. Then he placed the bat in the same bag. Standing naked, he said, "You better take your clothes off too. Stuff everything in here. Shoes too."

I did what he said. He tied up the bag and took it outside. I followed him. "I'll put this in the trunk of Bridey's car in the garage. We can get it out tomorrow. They might search my car. They won't search hers."

I was amazed at his calmness. We went back into the kitchen. Suddenly a light went on. "Who's there?" came a voice. "Who's out there?"

"It's me, Bridey. It's Constant. No need for you to come out. I was just getting a glass of water. Go back to bed. It's late. Sorry to disturb you."

"What are you doing up at this hour, Constant?"

"Go back to sleep, Bridey."

When the light went off, he signaled for me to follow him up the back stairs. He opened the door and looked out into the upstairs hall to see if his mother was up before making his way down to the room that we were sharing.

Inside, he said, "Take a shower. Quick. Use a brush on your fingernails in case there's dirt from the woods. Then get back in bed and try to sleep until morning."

He picked up the telephone and dialed. "Long distance? I'd like the number of Eloise Brazen. B-r-a-z-e-n. It's on Park Avenue in Manhattan. I'm not sure of the exact address. Somewhere in the 80s." He waited." Thank you. " He dialed again.

"Hello?" I could hear the sound of a woman's voice awakened from sleep.

"I would like to speak to Gerald Bradley. . . I don't have a wrong number, Miss Brazen. Please put my father on the telephone. Now... I know it's three o'clock in the morning. I am sorry to awaken you. Put my father on the telephone... Pa, it's Constant. Get home. Get home as quickly as you can. Get a car and driver... Yes, I am. I'm in some trouble. Trouble like you never knew... Not on the phone. There's been an accident, a terrible accident. They're going to say things about me that aren't true. But it was an accident. I swear to you, Pa. It was an accident.. .What? Yes, good idea. Phone Fuselli. Leave now, Pa. Hurry."

Constant stepped into the shower. He washed his hair. He washed his body. He washed his hands. He scrubbed his nails with a brush. He went to a bureau and took out a white Brooks Brothers shirt identical to the bloody shirt that he had just placed in the garbage bag. He put it on and got into bed. I stared at him.

"If they ask me for my clothes, I'll give them this shirt. It'll be used by morning. There's another pair of gray flannels in the closet."

"I don't have an extra pair of shoes, or another pair of trousers."

"I have everything, don't worry."

"Where's your blazer?"

"It must be in the Porsche."

He looked out the window. "Jesus," he said. He recoiled from the window in order not to be seen.

"What?"

"There are police cars on Scarborough Hill."

"What are they doing?"

"Driving slowly. Flashing the searchlights on the lawns."

I stared at the man who had been my friend as if he were another person, whom I did not know. Turning from the window, he looked at me.

"Why are you staring at me?' ' he asked.

"You have a cut on your lip," I replied.

He put his hand on the spot and walked to the bathroom mirror. He turned his head slowly from side to side, studying the blemish, as if it were an assault on his good looks rather than a possible clue to a murder.

"Constant," I said.

"What?"

"Why? Just tell me why. So I can understand."

He turned from the mirror and looked at me. "She screamed," he said without emotion. Horrified by what he said, I covered my mouth with my hand. He walked toward me, taking off his shirt as he did. It dropped on the floor. He stood naked in front of me, his hands on his hips. His body slowly undulated, as if in time to music. Then he put his hand on his penis and started to rub it back and forth. "Here. Take it," he said. "It's all yours."

"No."

"It's what you always wanted, isn't it?"

"No."

"Don't tell me no. I know you always wanted it. Here it is at last. Go ahead. Go ahead."

Two months later, Constant and I graduated from Milford. The Bradleys had the whole front row of seats that had been set up in the gymnasium for the parents and friends of the graduating class.

When our names were called and we went forward to receive our diplomas, no one received more applause than Constant Bradley. His family accompanied their applause with cheers and shouts, and a stamping of feet by his brothers, and Constant acknowledged his ovation with a wave and a charming smile. I realized that, in spite of what had happened, life would continue almost unchanged for Constant and his family. His mother and sisters, ignorant of the facts, would remain steadfast in their adoration of him. His father and brothers, who knew of his culpability, would overlook it, as if it were nothing more than a youthful prank that had gotten out of hand, the memory of which would be dimmed in time by his subsequent maturity and success. They believed in him. He was their hope.

When I went forward to receive my diploma, the applause for me was courteous, nothing more, despite the honors I had received, until a voice from the front row, Kitt's, yelled out, "Yay, Harrison," and her enthusiasm drew laughter from the crowd and an increase in the volume of applause. She was the best of them, and for that moment at Milford, all that I had witnessed such a short time before in the woods between the Bradley and Somerset estates seemed like nothing more than a nightmare from which I had awakened.

Later, lunch was served under a yellow-and-white striped tent set up in front of the Bradley Library, which was still under construction. Gerald pushed back his plate of lobster salad, gulped down his iced tea, and asked me if I would accompany him on a tour of the new building.

"You seem quiet," he said when we were alone.

"I have always been quiet, Mr. Bradley. I have simply become quieter."

"Why?"

"Because I am a participant in a cover-up. Because of what Mrs. Utley said on television—you must have heard Chief Quish speak for her when Gus Bailey questioned him. She said, 'Somebody knows.' I am that somebody."

"Who is this reporter, Gus Bailey? He persists in keeping alive a story that has run its natural course. He has suggested things about us, without calling us by name, because he knows I will sue if he does. He has made it appear that we have impeded the progress of the police. But he will stop. That much I know. Fuselli is doing a check on him. Where he's from. What he's about. Everyone has something to hide."

"Not Winifred Utley. She had nothing to hide," I said.

"Have you ever been to Europe, Harrison?" asked Gerald, shifting gears. He did not want to pursue my statement.

"No."

"Never been to London or Paris?"

"No."

"That should be part of every young man's education, such a trip as that. A great learning experience. Wouldn't you think so?"

"I suppose."

"They're going to say things about me that aren't true, Pa. But it was an accident."

He reached into his inside suit pocket and pulled out an envelope. "You will see that Sims Lord has drawn up the contract I spoke about some months ago. Any dealings through the years of your education you should take up directly with Sims. The tickets to Europe are a little graduation gift from Mrs. Bradley and me. You have been a wonderful friend to our son and to our family. You know that you will always be a part of us."

"You are sending me out of the country?"

"I am sending you on the trip of a lifetime."

"For how long?"

"Until university begins in September."

"Will Constant come too?"

"No."

"I suppose that would make it convenient for you," I said.

He paused before he spoke. "You're a curious boy, Harrison," he said. "Why in the world would my sending you on a trip to Europe, all expenses paid, the experience of a lifetime for a young man your age, make it convenient for me? Explain that one."

"You would then have only one thing to worry about: Constant. Instead of Constant and me. I am the wild card, am I not?"

"Wild card?"

"I suppose my proximity is a little unnerving during this period."

I expected his wrath, but that day Gerald held his temper in check. There was not an inkling of it.

"It is terrible that this suspicion has fallen on Constant. Terrible. The boy is innocent. His own mother saw him in bed at the time it happened."

"No, she didn't," I said.

He ignored me.

"There are terrible stories being spread about Constant. Buzzy Thrall, Piggy French, Eve Soby—that whole club crowd. They say that he roughed up Weegie Somerset last summer in Watch Hill. A lie. A terrible lie. Vicious. You know that. You were there." He plowed on with his diatribe, not allowing me time to either agree or disagree. "Constant is a good boy. We all know that. Careless occasionally, yes. Bad, never."

"Careless," I repeated, nodding at the word. "What an odd word for you to use."

He looked confused. "That's all Constant is. Good, but careless."

"Have you ever heard of Gatsby, Mr. Bradley?"

"Who?"

"His friend Nick said, about the Buchanans, but he might have been talking about the Bradleys, 'They were careless people. ... They smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.' I feel that I have been entrapped by Constant's carelessness."

Gerald appeared displeased. "It seems to me that this family is doing quite a lot for you," he said. With a sweeping gesture he indicated the contract for my education and support and the airline tickets for a summer abroad.

"It seems to me I am doing quite a lot for this family," I replied. I felt braver than I had ever felt in Gerald Bradley's presence. "I do not think you are getting the short end of the stick in this bargain, Mr. Bradley."

He ignored me. "I myself called on Mr. and Mrs. Utley. They, naturally, are distraught over their loss."

"May I ask you a question, Mr. Bradley?"

"What?"

"Have the police questioned Weegie Somerset?"

"Yes. And she denied that Constant had roughed her up. She said they had an argument and that was all. She said that nothing physical happened. I was able to tell that to Mr. and Mrs. Utley."

Then, from outside, came Kitt's voice. "Harrison, are you in there? Harrison?"

"I'll be right out, Kitt," I called back.

"Stay away from Kitt," he said, pointing his finger at me. " She knows nothing."

"Who does know?" I asked. "It would be helpful for me to know that. Does Mrs. Bradley know?"

"Good God, no."

"Maureen?"

"No."

"Who knows?"

"Jerry. Sandro. Desmond. Myself. No one else."

"Not Johnny Fuselli?"

"Yes, Johnny Fuselli. He would never talk. He works for me. I trust him totally. "

"And Sims Lord?"

"Yes, Sims. He knows. He is my lawyer."

"That's quite a lot of people to keep a secret, Mr. Bradley."

"That's my worry, not yours."

We did not look through the rest of the Bradley Library. It had merely been a place to be alone. He rose to go back to the tent.

But I still had things I needed to say. "Liquor does not elate your son, Mr. Bradley. It brings out the dark part in him. You should know that."

"You're making too much of this. Getting drunk is a thing all young men do when they're 17, or 18, or 19," said Gerald.

"Not Constant. There is no exuberance in Constant's drinking. No sense of wild oats. No fun. It goes straight to the dark side of him."

"Oh, please," said Gerald impatiently. "What dark side?"

"He killed a woman when he was drunk, Mr. Bradley. What's darker than that? What happened could happen again."

"Never. It was an accident."

"That's the party line, I know. 'It was an accident.' But don't use it on me. I was there, remember. I saw. And listen to what I'm telling you about Constant. It could happen again."

"I thought you were his friend."

"I am. Or I was. That's why I'm telling it to you."

He moved toward the main doors of the library, stopped, and returned to where I was standing. He reached into his pocket and brought out two envelopes. In one were airline tickets. In the other was my contract from Sims Lord. He dropped the two envelopes on a board that connected two ladders, and then moved outside to rejoin his family. He did not ask me to come along. I did not want to. I had been silenced by big money. My soul was lost, but my future was bought and paid for.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now