Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSingle White Phenomenon

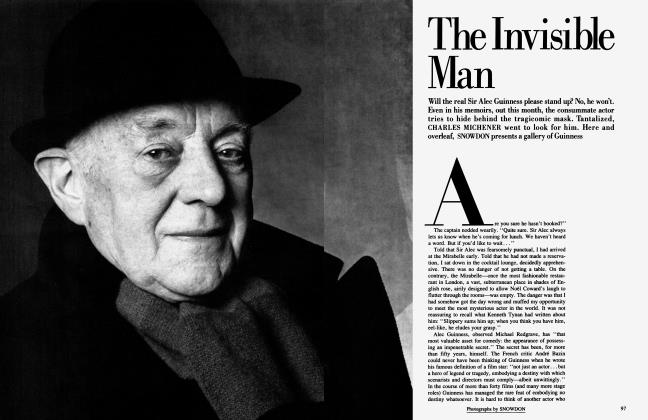

With a series of explosive performances, Jennifer Jason Leigh has exhibited an offbeat star quality that has made her one of the hottest actresses of her generation. KEVIN SESSUMS found her reaching for the next level as she tests her talents in three very different, very high-profile roles: as a phone-sex operator in Robert Altman's Short Cuts, as a screwball comedienne in the Coen brothers' new film, and, most remarkably, as the legendary wit Dorothy Parker

KEVIN SESSUMS

She will be a standard," director Robert Altman says, using a term usually reserved for a ballad made distinct by many different voices. He is escorting me into a screening of his next film, Short Cuts, a three-hour opus about Caucasian life in a terrifyingly self-absorbed Los Angeles, a city he accuses of ethical cleansing. "She'll be someone who other actresses will someday be measured by," Altman adds. Liza Minnelli rushes past us and, with her apologetic breathlessness, grabs a seat behind a graying Harry Belafonte. Altman smiles the ironic smile his films frequently elicit, then remembers what he was talking about. "Ah...Jennifer," he says with a sigh, all irony receding. "She's a killer in this part."

Jennifer is Jennifer Jason Leigh, and her part in Short Cuts' Nashvillelike ensemble is that of a phone-sex operator who works out of her home and fulfills her customers' most intimate fantasies while changing her baby's diaper or cooking her husband's dinner—neither aroma nor arousal flaring her nostrils. It is a dead-on, deadpan portrait, imbued with the quiet nobility of those uncannily American women weary of the latest wild frontier. Leigh has created a gallery of these ladylike lowlifes, including the whores with hearts of gold in Last Exit to Brooklyn, Miami Blues, and The Men's Club, the narc with a love for cocaine in Rush, and the mousy psychotic who borrows her roommate's identity as well as her sense of style in Single White Female.

I was always the good girl, and being the good girl requires a lot of suppression.

"I just bring some kind of truth to that person

"I got the feel of the character in Short Cuts by meeting all these women—and men—who do it," Leigh tells me at City restaurant in Los Angeles the day after the Altman screening. Famous in the film community for the exhaustive research she does for each of her portrayals, Leigh smokes cigarette after cigarette, which she blames on her upcoming role as chain-smoker Dorothy Parker, the legendary critic, writer, and lethal wit. ''I met a guy who also does it as a woman—he's this heavy-metal guy in the Valley," says Leigh, laughing at the incongruity not only of the sex operator's gender-bending performance but also of her current preoccupation with the more literary communication skills of Parker. Like Leigh's Tralala, the woman in Last Exit who hangs out with the coolest guys on her block and challenges them at their own game, Dorothy Parker hung out with her street's gang, those fellows on 44th—Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, George S. Kaufman—who formed the Algonquin Round Table, and added a bit of tralala all her own to the male trappings of that well-tailored tribe. Purchasable phone sex—a species of conversation not yet imagined at the time of their gatherings—would have been an interesting subject on which the Round Table could have offered up various fierce opinions. Leigh's: ''The men are so incredibly sincere on the phone while they're jerking off, and the people doing it couldn't give a shit. It's all in a day's work, basically. It still infects their psyche, though. It can't help but do that."

And how about hers? Why does she choose such out-of-kilter and courageously lurid roles? ''I just look at them as human beings and bring some kind of truth to that person we have very preconceived ideas about. We're all fascinated with darkness, because we're all afraid to live that, but if we have a chance to witness it, we will. I do think that people's sexuality is one of the ways in which they are defined. But it is a very private way. So to show that private behavior in a film—if it's not just a fluffy love scene that's made to make the actors look beautiful in golden light—you can really show something about a person's longing or their lack of feeling or their desperate want to connect. There is just something in that you cannot see in another part of their life. . . . Those are just the best acting parts out there... A lot of times women are either saddled with playing the executive, which is too boring, or the girlfriend, which is simply to prove that the guy is straight. That has no interest to me."

But are these parts, involving characters who are sexually exploited by others, or violently raped, the politically correct roles for a young actress to be accepting as she builds her career? (In The Hitcher, Leigh is tied to two diesel trucks and torn apart.) ''I make my own judgment calls," she says. ''So, no, I think that these women exist in society, and they are just as heroic and they go through just as much shit and they have just as much to say about the conditions of women in America as any other woman in America. I think it's kind of immoral to say that we shouldn't show prostitution on film. It's a part of our culture. If we can portray it honestly, or have a film that has something original to say about it or shows it in some light that isn't exploitive, then that's interesting to me."

It is interesting to her family as well. ''I don't look at her as my daughter when I'm watching her on-screen," says her mother, writer Barbara Turner, who discloses that Leigh was painfully shy as a child. ''I look at her as an actress. The sexual parts don't bother me. It's the violence that gets to me. I'll admit, when that happens I'll turn away from time to time."

Leigh's older sister, Carrie Morrow, now living in Minnesota, is the person whom many of her earthier performances may be loosely based on. Growing up, Leigh was always the ''good girl," by her own definition, and Carrie, who at one point worked as a carny barker, was the wild one. ''My older sister was always very, very gut, very emotional. Everything came out. I was just the opposite. I was someone who saw things come out, but then became very, very intuitive. I really formed myself by watching Carrie in a certain way." Leigh's character in Rush was based to some extent on Carrie's problems with drugs. Now (Continued on page 137) (Continued from page 97) clean and recovering, Morrow has only praise for her younger sister. "She used to see me get into so much trouble all the time, and she really protected herself from that," Morrow tells me. "I just adore her. Literally, she's been a big part in saving my life."

we have very preconceived ideas about."

"Her choice of roles doesn't surprise me," says her younger sister, Mina Badie, who is also an actress. "I would always hear about them before I saw them. I would also hear about her perceptions of each character. The first thing out of her mouth was not that this girl was a prostitute. The first thing out of her mouth was that this girl is naive and thinks that life is wonderful and everything in life is beautiful. So I saw the reasoning behind the character before I saw the character."

Though Leigh is extremely close to her mother and sisters, she has still not created a family of her own, and is surprisingly unapologetic about it, considering the neo-nesting atmosphere so prevalent in the Hollywood of the 1990s. "I just don't feel at all ready to have children right now. I don't. I would want to want to have children. Hopefully in the next 10 years I will." Having dated actors David Dukes and Eric Stoltz in the past, Leigh turns coy when pressed to describe her current private life. "I'm in a relationship that I've been in for a number of years now. He is not an actor. He is not an actor. . . . It's just so important to me to keep my private life private. I personally don't like reading about people's private lives. It makes me cringe."

Leigh's next two roles are great leaps forward for her—if not on a performance level, at least on a sociological one. In addition to playing Dorothy Parker, she will be seen as the female lead in the Coen brothers' next film, The Hudsucker Proxy, which co-stars Tim Robbins and Paul Newman. In it she must rattle off her part with the feistiness of a Jack Russell terrier and the timing of a Rosalind Russell heroine. A 1950s Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter on an investigative assignment, she exposes the corporate shenanigans behind Paul Newman's machinations while at the same time falling in love with Newman's dupe in the film, Tim Robbins. The Hudsucker Proxy has the atmosphere of a 1930s screwball comedy, and some would say that Leigh, because of her past work, is a curious choice to play the reporter. "She's a chameleon,'' Joel Coen says by way of explanation. "And she can talk real fast,'' offers his brother, Ethan.

"I still wake up some mornings not believing I got the part in The Hudsucker Proxy—that I actually made the movie,'' Leigh admits. "When I first got the part, I thought, Oh, I will die before I make this movie. I even investigated getting a new car with air bags, because I thought there is no way that my life can be this good.''

After the very public tragedy of her father, Vic Morrow, being killed in a freak helicopter accident on the set of Twilight Zone: The Movie, it is understandable why Leigh is skittish about her good fortune. Never close to Morrow when he was alive (she was born Jennifer Leigh Morrow, discarded her last name, and borrowed "Jason'' from family friend Jason Robards), the 31-year-old actress seems to have grown closer to him in death. The night after the accident, she, her mother, and her older sister got a print of Blackboard Jungle, in which Morrow starred as a young punk, and watched it while sharing memories of him—a touchingly Hollywood way to mourn a father's death. That was 11 years ago, yet it is still a subject she steadfastly refuses to discuss. "Something like that is not something you get over,'' she states, telling me that she has been in therapy ever since the accident happened. "It's not like being sick and then suddenly you're well and you can't remember the pain of it. I think the death of a parent is something that you work through. It changes you forever. It's something you're constantly working on and finding out about. It's nothing I talk about, really. I talk about it in therapy, but I don't really even talk about it in my friendships very much.''

One of Leigh's best friends is actress Phoebe Cates, who co-starred with her in Fast Times at Ridgemont High. "She does not have a mean bone in her body— not one," says Cates. "The funny thing is that the director Paul Morrissey once gave me a copy of Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell Is This?, and when I read it—this is way before Jennifer was going to do Miss Parker—I thought, Who could play this part? And there was nobody other than Jennifer that I could imagine doing it."

Neither could Robert Altman, who is producing the film, in which Leigh must age into her 60s. At his Fourth of July party last summer, Altman escorted Leigh over to meet the film's director, Alan Rudolph. "Alan, this is Jennifer," he said. "I really think she would be great as Dorothy Parker." The next day Leigh received a script, and soon met with Rudolph in a local coffee shop to discuss the role. Other cast members include Lili Taylor as Edna Ferber, Campbell Scott as Robert Benchley, and Matthew Broderick as Charles MacArthur. In the February 1919 issue of Vanity Fair, Dorothy Parker, in her role as drama critic, wrote of MacArthur's future wife, Helen Hayes, in a production of Dear Brutus: "Hers is one of those roles that could be overdone without a struggle, yet she never once skips over into the kittenish, never once grows too exuberantly sweet—and when you think how easily she could have ruined the whole thing, her work seems little short of marvelous. I could sit down right now and fill reams of paper with a single-spaced list of names of actresses who could have completely spoiled the part."

Parker could have been writing about the actress who, more than 70 years later, would be portraying her. In fact, Leigh is something of a critics' darling. The New York Times especially heralds her performances. Janet Maslin, writing about Miami Blues, in which Leigh co-starred with Alec Baldwin, noted that "Miss Leigh . . .steals every scene with Susie's impossible ingenuousness," and Maslin's fellow critic Vincent Canby went even further in his review of Single White Female. "Ms. Leigh continues to astonish," he wrote. "It's difficult to recognize in the lunatic Hedy the same woman who played the innocent hooker in Miami Blues and the frail, lost Tralala in Last Exit to Brooklyn. She's become one of our most stunning character actresses before looking old enough to vote."

Leigh is a bom child of Hollywood. "I grew up two blocks above Hollywood Boulevard," she reminisces. "When I was growing up, Hollywood Boulevard was so safe. I mean, at six years old my friends would come over to play, and we would walk down Hollywood Boulevard, go play in the Wax Museum, play at Grauman's Chinese Theatre. It was really safe and wonderful and fun. We'd walk backwards and read the stars in the sidewalk. When I was around 14, I remember, Lee Strasberg had a summer studio session for kids, so I'd walk down there. ... I was always the good girl, and being the good girl requires a lot of suppression—suppressing the animal parts. When I was a child and I would playact, all those parts would come out. They are both true parts of me—one is the part that I live, and the other is the part that I act and can live with at a safe distance. Acting has been a real lifesaver for me—-from childhood. It's partially a genetic thing and partly environmental."

"Is it a way of loving your father?"

"Well, I don't know about that, because I always did it from such an early age. Not professionally, of course, but as a means of being with people. It was as simple as that: just being among people. On a deep level, it has more to do with who I am than who my father was. In nursery school it was: Let's play house. In kindergarten it was a production of The Wizard of Oz. I put the whole production together. My best friend played Toto. On a leash."

"And what part did you play?"

"Why, Dorothy, of course," Leigh says, her voice suddenly filled with a haughty and haunting dismissiveness. It is as if the Kansas Dorothy of her past—the yearning, youthful basis of all her characterizations, it would seem—had parked herself here at our table only to acquiesce to the cantankerous Algonquin queen already in our midst.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now