Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Fame of the Rose

In the staid corridors of PBS, a bright, dashing southerner named Charlie Rose has created a talk show that gets talked about almost as much as Rose himself. But his meteoric rise left critics claiming that his celebrity had gone to his head. When his very public breakup with socialite-activist Amanda Burden stirred a wicked backlash, the sharks gathered. The current question: Has Has his his frenzied life life off-camera off-camera started to eclipse eclipse his his on-air on-air tr triumphs? ELISE ELISE O'SHAUG O'SHAUGHNESSY considers considers the man who who fell fell to earth

ELISE O'SHAUGHNESSY

Charlie Rose was not happy about the idea of being profiled in Vanity Fair. In fact, his response was surprisingly violent: "No, ughhhh, no, yecch, all this stuff about me, there's been all this stuff.

... It's boring, I'm overexposed, there's nothing to say... . The answer is no...," etc. Perhaps, for all his self-professed naivete, Rose sensed a whiff of blood in the air: his own. It would take a month of phoning and cajoling, of skittish, guarded, and sometimes off-therecord exchanges, before he consented to an interview. He was reeling from some tough punches, both personal and professional.

Once he decided to talk, the phone calls started coming my way. His P.R. company, the Susan Magrino Agency, dispatched helpful faxes with the names and numbers of people he thought I should speak to. Included was legendary talk-show host Jack Paar. "I don't know him that well,'' said Paar, echoing many of the people on Rose's list. "But he's one of the best things on TV. I keep writing him and telling him to comb his hair. It can't be that windy in that studio."

Paar, who never thought of himself as doing a talk show— "It was conversation"—sees Rose as having picked up the conversation "after an interim of 15 years when nothing happened." Charlie Rose has filled that void with his PBS show, making things happen in the difficult hour between 11 and midnight. On-air, all the windblown Rose has to work with is a round table, his guests, and his energy, which is tangible. Except for a taped show on Fridays, this highwire act is live, without a net, and it is frequently dazzling.

Bill Moyers recalls talking to scholar Leonard Levy some years back, when Rose was hosting CBS's Nightwatch: "Levy spent his life studying the Constitution—he has no interest in TV. He told me, 'The only television I watch is Charlie Rose. He brings the world to me so enthusiastically that I can't help but listen.' " Words like "enthusiasm," "intensity," and "drive" often figure in discussions of

Charlie Rose, even discussions with those who think that Rose's passion is primarily for his own voice and his position as one of the names that appear in boldfaced type.

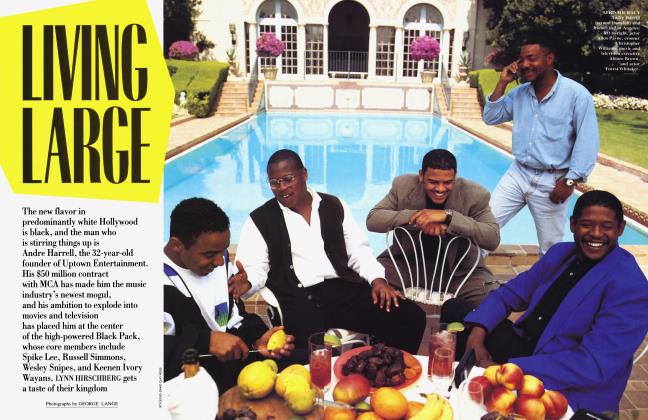

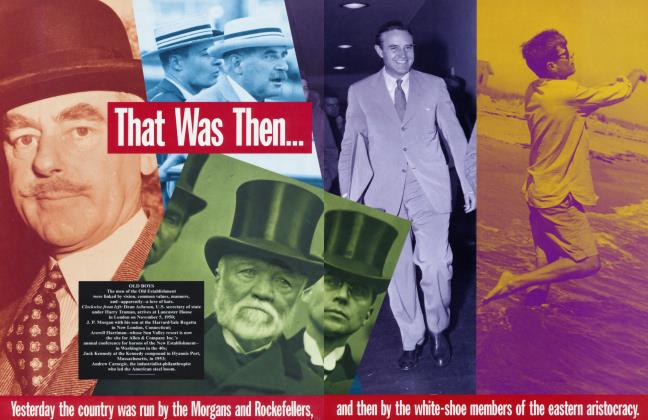

When Charlie Rose began broadcasting to the heartland of the media industry in September of 1991, it brought New York's cultural elite to its feet. "My New York friends all race home from dinner parties to watch it," says Tim Russert, host of NBC's Meet the Press, and after the show went national in January of this year, plugged-in viewers in other cities could tune in to catch the rhythm of New York's intellectual tides. Colleagues applauded the show as "the last refuge of intelligent conversation on television," as Morley Safer puts it. They were equally approving of its tall, southern 51-year-old host, who was suddenly white-hot at A-list parties and benefits.

From the outset, there was only the thinnest of membranes separating Charlie Rose from Charlie Rose. The man was seen in Southampton with society doyenne Brooke Astor; the show received funding from the Vincent Astor Foundation. The man dined at Mortimer's with Wendy Wasserstein, Mike Wallace, and Mort Zuckerman; the show received them as guests. And although his girlfriend, Amanda Burden, never crossed the line between man and show, the beautiful, wellconnected daughter of Babe Paley was certainly a lustrous addition to the Charlie Rose image—as he was to hers.

"He's attractive, he's single, he's straight," says Liz Smith. "So how could he fail?" Well, in the media kingdom there is a price attached to such rapid, glittering ascents. The chorus had sung hosannas to Rose; now it was time for a little Charlie-bashing. One of the reigning pundits describes Charlie Rose's current dilemma this way: "It's like that scene in Mary Poppins where the wind suddenly changes."

The first hit came in January, from Walter Goodman of The New York Times, whose cutting review—"No ego is so bloated that Mr. Rose cannot puff it up further"—appeared the very day P.R. guru John Scanlon threw a party at the venerable Century Club to celebrate the national launch of Charlie Rose. Rose's ingratiating manner had been slammed before, but never with such force. A few months later The New Yorker took Rose to task for "beaming out of the bubble of his celebrity status," and described him as "the literati's latest lovesicle." Viewers and critics groused that he interrupted his guests, that his questions were conversations unto themselves—in short, that the talk-show host talked too much. ("He has to learn to listen!" Paar said.) Yet another New York Times piece quoted Mike Wallace as saying there were moments when "I want to shout at the screen, 'Shut up, Charlie!' " According to several people close to Rose, the arrows went straight through his very thin skin.

Media commentator Ken Auletta characterizes the prevailing attitude as " 'Let's chew on Charlie Rose's leg today—he looks like a success.' His success is getting reviewed. Then your lifestyle gets reviewed." When it came time to review'Rose's lifestyle, he was an easy target. Like any country boy who has waited a long time for the homage of the big city, he seemed to enjoy the hoopla so much. One friend (Continued on page 243) (Continued from page 174) describes him as getting "swept up" in his newfound prominence; a less indulgent observer notes that "the way he has handled his time as a known entity is disgusting." His glamorous socializing was dangerously akin to social climbing. His constant name-dropping, both on and off the air, began to grate. His frantic pace and unswerving fixation on his show looked at times like egomania.

"You need to learn how to act, be nice, return favors," says Liz S,ith. "Charlie hasn't learned any of that."

Liz Smith, who did a great deal to launch Rose into the dangerous media waters, has nothing but praise for his work. "He seems to have a personal integrity about what he does on the air." But, she adds, "he doesn't have a handle on how to cope with public exposure, with his new status. He seems ragged, frazzled, frayed. Every celebrity needs to solve the public-private persona. You need to learn how to act, entertain, be nice, return favors. He hasn't learned any of that." Mike Wallace, who wrote Rose a note reaffirming his admiration in the wake of the New York Times review, also thought Rose had been looking "a little distraught" lately.

Rose has always had a somewhat frayed and frazzled manner; the on-screen energy has its cost. His patron and friend Brooke Astor wishes he could slow down, but says "he seems to be a glutton for punishment." Even the message on his answering machine sounds as if it had been taped

in a burning building. But what seems to have pushed him close to frenzy was the painfully public end of his relationship with Amanda Burden.

Since the long-divorced Rose arrived in New York, there has been constant interest in his romantic life. Was he going out with editor turned literary agent Joni Evans? Was he seeing playwright Wendy Wasserstein? (Both women describe themselves as friends.) In January, New York Newsday devoted a lengthy article to his powerful effect on women. Even Jack Paar was curious about Rose's life and said his wife wanted to know whether Rose was married or not—"He has an enormous appeal to women, a real matinee-idol type."

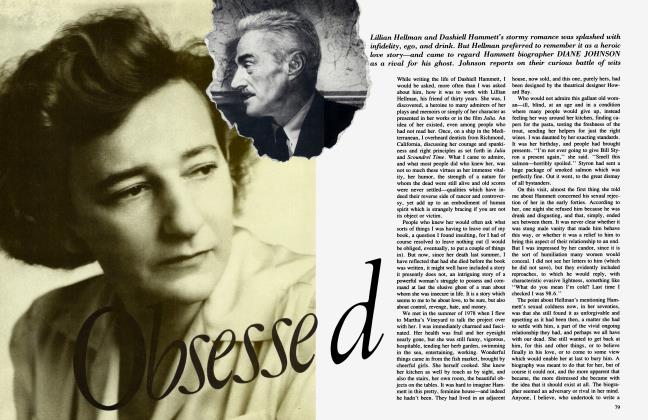

It caused a stir when he started seeing Burden, in early 1992. Amanda Burden is a true princess of the city, and in the late 60s and early 70s, she and her first husband, Carter Burden, reigned as New York's golden couple. Her divorce from Carter was followed by the briefest of marriages to Time Warner mogul Steve Ross, and her name has also been linked with Senators Ted Kennedy and Christopher Dodd.

Burden, who lives on the Upper East Side in a Mark Hamptonesque apartment with two pugs and a freezer full of Lean Cuisine, inherited an estimated $18 million from her stepfather, CBS chairman William Paley. But she works hard, both

as a member of the City Planning Commission and on the coordinating staff for the Midtown Community Court. Recently, she earned her master's degree in urban planning from Columbia University, winning a prize for her thesis on the classic New York topic of garbage.

The relationship between Burden and Rose deepened after a late-spring weekend at his farm in North Carolina in 1992, and he became extremely possessive, to the point where he objected to her dining out with a male friend. Mike Wallace, on the phone from his house on Martha's Vineyard, recalls that a year earlier the couple had been in that very spot, for Wallace's stepson's wedding, and that "Amanda was obviously nuts about him—and he about her." In the months that followed, they appeared together at charity events and dinner parties, though Rose would generally have to slip away after the first course. Last fall, there was a temporary cooling off: "Charlie wasn't being attentive enough," says a source, but on the whole they seemed "like a young couple in love," as one socialite describes it. Sometimes, Rose would pick Burden up after the broadcast and they'd head down to SoHo for a late dinner at Felix. Early May found them dining en famille at the restaurant 44, with Amanda's son, Carter (she also has a daughter, Flobelle), and Carter's girlfriend. After they decided to rent a summer house together in Bellport, Long Island, there was speculation that the next step would be marriage.

All this culminated in what may have been the most high-profile romantic breakup in New York since that of Donald and Ivana. First, there was just a simple announcement of the split, made most tastefully in Liz Smith's column (though not, says Smith, by either of the principals). But over the following days additional gory details—including the revelation of a "Madame X"—were sprinkled throughout the gossip pages. Rose had always had a reputation as a flirt; now he was seen as a cad, and certain New York hostesses were no longer quite as eager to seat him at their tables. "They see him as an operator," says one social insider. At book parties, on the phone, lunching at the Royalton, the chattering media elite were no longer discussing his show. They were asking each other, "Do you know who Madame X is?"

As one of her close friends tells it, on June 10 Burden was accosted outside her office by a tall, striking woman in her early 20s with a mass of platinum hair, who asked to speak with Burden in private. Burden took her to a conference room, where the woman produced a card bearing

the name Carolyn S-, and said, "I

don't think you know about me, but I'm Charlie's girlfriend, we're in love with each other, and I'm going to have Charlie's children."

Burden was stunned and incredulous. Carolyn offered proof, dialing her own voice mail and having Burden listen to an intimate message from Rose, and showing her photographs. Carolyn said that although she saw Rose frequently, they rarely went out in public together because he preferred home cooking to eating in restaurants.

Rose did take Carolyn out publicly on at least one occasion, however: for a tennis game with Joan Cullman and her husband, Joseph, chairman emeritus of Philip Morris. Joan Cullman says she subsequently lunched twice with the young woman, who works in advertising. She was quite cool and self-assured, and the growing public relationship between Rose and Burden "didn't seem to faze her," Cullman recalls. In fact, Carolyn's attitude was that "Charlie has to do what he has to do."

Clearly, at some point, that attitude changed. I asked Rose about the story that his relationship with Burden had been broken up by another woman. "Have you been told that by Amanda?" he asked. No, I said. "Then I would be very careful about that." Was he saying it was untrue? "I'm just saying be careful."

Very slowly, with an unwavering gaze and lengthy pauses, he launched into a veritable catalogue of Burden's virtues, including her social commitment and skills as a tennis player. He closed with the following declaration: "I love her very much. And I always will. For a while, for a brief, all too brief time, we had a magical relationship. She occupies a special place in my heart and she always will. Nothing that she says or does, or anyone else, will ever change that. My experience with her changed my life. She taught me wonderful things. . .. And I shouldn't say even that much about her. ' '

A source close to Rose says that though Rose had been seeing Carolyn when he met Burden, "in his mind it was off and in her [Carolyn's] mind it wasn't off." Burden's friend says that when Burden confronted Rose he told her that it was a one-night stand. But from Joan Cullman and from an old friend of Rose's named Bill Wright, Burden learned that Carolyn had been in Rose's life since at least 1990, and had been sharing his apartment until last year.

Burden has been unyielding on the subject of Charlie Rose. "He is not the man I thought he was," she told me, as she has told others. Many New York arbiters felt the same way, and the story fed the growing backlash that afflicts those whose profile has become too high, who are, as Rose himself sensed, overexposed.

Joni Evans, herself no stranger to public setbacks and well-documented domestic drama, points out, "We tend to tear down what we just built up. We discover someone, fall in love with them, then tear them down. Charlie can't compete with the person we made him out to be."

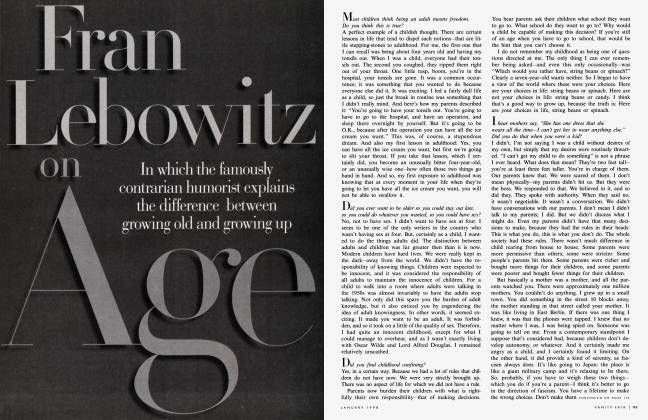

/^\n one of the hottest days of the sumv^/mer, Rose rushed into the lobby of the WNET building on West 58th Street, a bit damp after a mad dash from his high-rise building two blocks north. The apartment, which is packed with what he has described as an "embarrassing amount of electronic equipment," gives Rose a stunning view of the city. One visitor describes the decor as tastefully unmemorable yuppie. The same description could have been applied to his suit, which was dark and well cut, enlivened only by one of the funky ties that have become his trademark.

We made the Charlie Rose progress to his lOth-floor office, his staccato energy in full evidence as he chatted with the guard in front of the elevator, called out greetings to staff in various offices along the hall, checked his mailbox, hugged his assistant, Yvette, riffled through papers, and muttered some quick decisions on a few urgent matters. He was obviously not looking forward to sitting still as yet another writer squinted at his flaws. Eventually the flurry of activity died down and we were finally settled in, my tape recorder on, his tape recorder on.

"I reread the clips," he said, "thinking that if everybody's reading the clips as the basis of an interview, maybe I should read the clips and see what's in them." (He was referring to the fact that I'd told him I'd read everything printed about him, and to his fear that this would produce a regurgitation of what he calls "the great misperceptions about me.") "I generally read them once and forget about it, don't reread them, don't agonize over them."

As candor goes, it wasn't a promising start. We went on to spend an inordinate portion of the next two hours in heated wrangling about how often Charlie Rose goes out. It is clear that of all the things that have been written and said about Rose, the one that drives him truly crazy is the suggestion that he has become a fixture on the social circuit. He argued long and hard that he doesn't go out as often as people think he does. "There's nothing wrong with it [going out]," he said, irritably and repeatedly. "It's just that I don't do it as much as you imagine."

The discussion deteriorated to the point where he blurted in exasperation "I'm guilty! I'll never go out again!" before we pulled ourselves together. I was persuaded that he'd gotten more attention for his social life than a strict log of parties attended might warrant, and felt a little bad that he was having to make his case to someone who he knew would be seeing him at a book party in a matter of hours.

The other thing that bothered him was the idea that his protracted hunt for an executive producer had become a running inside joke in Manhattan circles. The wags had it that Rose had found the ideal excuse for engaging in endless discussions of his show and his vision. He had sought advice from so many media opinion-makers that his search—what he preferred to call an "exploration"—was chronicled in The New York Observer (one of the many clips he read once and then forgot about).

Though everyone agreed that Rose was in dire need of an executive producer, the job had been vacant since Arden Ostrander left in July of 1992. One television veteran claimed the job had been turned down by 20 people. Others believed that Rose didn't really want to fill it. "He likes being a one-man band," says a colleague from Nightwatch days. "He would grab a preparation packet and walk away while you were trying to make a point. He thinks he knows better, but he takes the packet. It was as if he resented the fact that he needed you."

Rose denied that he wants to do it all himself. "I've just been so busy doing the show that I haven't focused on it," he explained. "I will have an executive producer and a managing editor before this article hits the newsstands." This didn't mean that "I couldn't have managed both," he continued. "Clearly I could have.

... Yes, I have been doing the work of three people, sure." (But finally in late July, Rose gave up the one-man fight, offering Peter Kaplan, an editor at Conde Nast Traveler, the executive-producer job.)

r 11he Charlie Rose of today is defensive X and tense, sadder and perhaps wiser than the man whom I first met at Arcadia for lunch in June of 1992. Rose began our meal by playing the North Carolinabumpkin-loose-in-the-big-city, but he was relaxed and good-natured when the act was greeted with skepticism. In that first interview, all his charm was apparent. Despite the difficulties of promoting a show whose budget was so low the staff occasionally resorted to stealing the daily newspapers from Bill Moyers' office, the mood was upbeat: At first, Rose had relied mostly on guests who had gotten to know him from Nightwatch, but the momentum was building. He would shortly get the future president of the United States to sing an Elvis tune ("Don't Be Cruel") on the air, an event hailed as one of the highlights of a show-biz election.

Rose talked at length about the show, but he was almost as voluble on the subject of his 500-plus-acre soybean farm in Oxford, North Carolina, near his hometown of Henderson. He purchased the farm to be near his mother and father just before the latter died in January 1990. There's not usually a lot of talk about foaling and birdsong at Arcadia, but Rose's country-boy act seemed most genuine when he talked about his roots and family. Businessman Bill Wright, who met Rose during law school at Duke and has remained a close friend, admires him for, among other things, "his wonderful relationship with his mother. He goes down there a lot," says Wright, pointing out that it's a long haul from New York.

Growing up as an only child in the rural South, Rose displayed the classic symptoms of proto-ambition: an awareness of and a yearning for the world beyond Henderson. He loved the information programs on radio and TV, and, as he remembered, "you'd wait for Wednesday 'cause you got Time on Wednesday and it told you what was going on." Sometimes he'd watch the trains which ran by his father's general store, dreaming about the day he would ride one to wherever it went.

When a local business held a contest, for which the prize was a shot at playing disc jockey on the local radio station, he entered several times and eventually won. "I wanted just to be on the radio," he said. "It sounded like a wonderful thing to me. To talk. It was mainly to talk on the radio. I wasn't all that interested in playing records." In a self-mocking tone, he added, "Even then, he wanted to hear the sound of his own voice."

Rose loved that first taste of live broadcasting, but "I didn't think of it as a career, because I didn't know any broadcasters. If I was looking for role models, it was doctor, lawyer, businessman."

He tried all three—taking pre-med courses at Duke, going to law school there, and then heading to New York for a short career as a less-than-halfhearted banker— before he found his way back into broadcasting. His then wife, Mary, whom he had met at Duke, got a job in television; through her he landed one day in the office of Bill Moyers.

"I said to him, I don't know much about television. And he said, Neither do I. And that's the way we started. It was fun, and it made all the difference. And we learned a lot. I mean, I wasn't very good, but what the hell. I learned. I got better.

"And he pushed me out front. I had no great overwhelming desire to be out front. ' ' But he liked it? "I loved it."

Moyers talks about his protege with admiration, and with the understanding of a fellow southerner. He sees Rose's constant on-air interruptions and interpolations as "inner energy. He engages almost physically in the conversation. . . . In the South, to talk is to be. That's Charlie. That's as natural to him as control is to Koppel or hype is to Donahue.

"He was the same way 20 years ago," Moyers continues, "almost needing to physically touch people. I think he'd be a natural for southern politics. He cares about the things politicians should care about. I told him I thought he should go home and get into politics. But the camera was like a magnet drawing him."

The camera drew him to Washington, D.C., to Chicago, to Dallas-Fort Worth, and back to Washington, mostly as host of one talk show or another. He cites the fact that he was a "selfish workaholic" as the reason his marriage ended along the way. Then followed the six long, muffled years at CBS News's Nightwatch, where Rose played host to an impressive array of guests and won an Emmy for his interview with Charles Manson. Jessica Matthews, a friend who saw the uncut three-hour tape of the Manson conversation, describes it with awe: "At the beginning, Manson was really crazy. Slowly, somehow, Charlie found a plane on which he could talk to Manson—a sort of crazy plane, but he could talk to him. . . . The first halfhour, anyone would have said this is a waste of time. . . . But Charlie found a level on which to engage Manson and then finally brought him down to a more sane plane."

Such achievements didn't alter the fact that Nightwatch was definitely the farm team, airing between two and six A.M. to a small, if fiercely loyal, audience of insomniacs—including network chairman Larry Tisch. And despite that powerful fan, the show's budget was gradually whittled to the bone. "It was agony," Rose recalled over our lunch. "It didn't have a constituency within CBS.... It was in Washington, not in New York— out of sight, out of mind. It was on at a time when nobody saw it."

His decades in the outer darkness of regional and late-late-night television made it even sweeter that he was now the budding toast of New York, receiving the rapt attention of his peers, being able to call up places and have people know his name. "I feel like I'm at the center of whatever," he said, but followed that happy statement almost immediately with a verbal fidget: "I'm worried about tonight, we're missing a segment for tonight."

When Rose left Nightwatch in 1990, it was after some frustrating conversations with the CBS brass. They wouldn't give him the 11:30 slot or a chance on the morning show. "I pushed him as hard as I could," says Frank Stanton, who was the network's vice-chairman. "But I couldn't budge the people on the programming side." Why the resistance? "Ironically, [Bill] Paley had sounded off about not liking Rose."

Van Gordon Sauter, former CBS News president and now head of Fox News, recalled that "Charlie was not the most popular person at CBS. His resume was not clubbable. People thought he'd appeared from nowhere, that he hadn't paid his dues. He hadn't been in the L.A. bureau covering floods."

Rose's next stop would be Los Angeles, not to cover floods, but to create and host a half-hour show for Fox called Personalities. He hoped—perhaps naively, perhaps out of blind, romantic ambition— to interview the likes of Dianne Feinstein, Isiah Thomas, or Jonas Salk. But, as one staff member later recalled, Fox looked ''at every 10th of a rating point. And we could do the most urbane, witty show and executives—nice guys—would say, 'You know, Inside Edition is doing the Kennedys, they're killing us.' Or 'Inside Edition is doing Nazis.' "

The camel's back broke the night Rose found himself reporting on an alleged curse afflicting Monaco's royal family. He concluded that Fox ''misled me—and I think they misled themselves. . . . They said to me, in print, 'This is not a tabloid show.' And it was. And it offended me. . . . I could have said, 'Just hang in there, you're making a ton of money.' I'm constitutionally incapable of doing that."

He walked away after only six weeks, and headed for his newly acquired farm. For a year, he waited, mourning his father's death, learning how to manage his property, looking for his dream show.

His friend Bob Costas believes Rose found that show in September of 1991, after Frank Stanton set up a meeting between Rose and the top people at WNET. "It is very, very difficult in broadcasting, no matter how good you are, to find circumstances that are perfect for you," Costas says. "Even very successful people don't have circumstances that are perfectly matched to them."

I,1 ven with a show that is perfectly -Limatched to him, what Charlie Rose does is not as easy as it looks. Take the choice of guests. In part because New York is a media town, Rose books a healthy number of print and broadcast journalists. Some may ask, Do we really need an hour with Howard Stringer? But many dote on the opportunity to "watch Mort Zuckerman free-associate for 30 minutes without a net." And, from the beginning, those media guests fed the buzz about Charlie Rose, and gave it an inside feel. Since the show went national at the beginning of the year, it has pulled in some bigger and more elusive names, and that's where Rose's overhyped partygoing has reaped its reward. He has collared Barry Diller, Pat Riley, and Ralph

Lauren. "Connie Chung's people want to know, how did we get Ralph Lauren?' ' says producer Emily Lazar. "Charlie booked him at a dinner party."

On Charlie Rose, Roseanne and Tom Arnold rub airwaves with architect Frank Gehry; a health-care panel gives way to Carly Simon and Wolfgang Puck. Henry Kissinger is followed by Henry Winkler, who is followed by Calvin Trillin. Despite this diversity, Rose is at heart a political junkie, broadcasting every Wednesday from Washington, D.C. And he often changes the guest lineup to respond to the news, for instance pulling in Middle East experts Judy Miller and Fouad Ajami for questioning on the heels of the arrest of New York's would-be bombers.

Amazingly, given the breadth and depth of the interviews, all the guests I called gave Rose high marks for his knowledge and preparation. Writer and jazz critic Stanley Crouch, a frequent guest, cites Rose's intelligence, his interest in the material he's addressing, and his ability to sustain "high-level engagement." And, he adds, Rose is willing to go with the flow. "If he brings you on for 10 minutes, and he likes what you do, you'll be on for half an hour." An interview with John le Carre was the perfect illustration of what Bob Costas, host of Later, describes as the show's strength. "People know they're not going to be sound-bitten. They are willing to venture into areas that require subtlety and shading."

If Rose gushes a bit, that's because "you have to make your guests feel comfortable," argues Bill McGowan, who worked with Rose at Nightwatch. The seemingly genuine interest and admiration he brings to almost any subject make his guests open up. Talk-show hosts are in the business of straddling a line, says Arden Ostrander: "Charlie does this better than most." Nick Dolin, a Charlie Rose producer, points out that "the proof is in the answers. And Charlie gets the best answers."

But what about the people who spend that hour outside the magic circle of light that bathes Charlie's simple round-table set—the people who work with him? Are they as enthusiastic as his guests? Former colleagues use words like "dysfunctional" and "megalomaniac," and describe Rose as having a complete lack of respect for the contributions of his co-workers as well as an unattractive compulsion to grab for the spotlight. Off the record, of course. McGowan, who is now at A Current Affair, says he's surprised that "a lot of people have become chicken about talking about what Charlie's really like." But when McGowan was recently quoted in The Washington Post as saying that guests "will go on and be pretty confident that what they do for a living will be called 'a craft' and the way they do it will be called 'genius,' " it didn't matter that he went on to point out that "it's to any talk show host's advantage to do that." Rose called McGowan and made his unhappiness very clear. It was not an isolated incident. Despite his claims to the contrary, Rose cares almost to obsession about what people say.

But the current wave of negative press is ultimately irrelevant to Rose's professional future. "For better or for worse, print has very little effect on television," says Bill Moyers. With David Letterman and Chevy Chase joining the late-evening lineup this fall, Rose's long-term problem lies outside New York, in establishing himself with PBS stations across the country. Ultimately, those stations are where the support for his show must come from, and they are as ratings-driven as any network affiliate. According to the latest Nielsens, Rose's national rating is still a tiny 0.4 (550,000 viewers). "All this adds up to something that is still very tentative," says one industry source.

"r I ''elevision occurs only against enor-

X mous inertia," says Bill Moyers. "You don't survive in this business unless you fight to control what you do, to keep it from other people's aspirations.... In this business, people will take it away from you if they can."

Rose would say that some of his most annoying habits are part of the fight to survive, to maintain control and quality. His penchant for dashing down the hall at the last screeching minute before airtime must cause ulcers among his staff (reportedly they have a pre-taped show stashed away against the night he cuts it too close). But this bit of drama, like his practice of not chatting with his guests beforehand, is a way of pumping himself up on a nightly basis. Without a band, or an audience, without "all these external elements that can add to the excitement, you have to create it and you have to create a chemistry," he explained. "And it's harder to do that if you're sort of sitting around and energy's going here and going there,

rather than sitting down and boom"—he struck the desk—"going, like that."

He believes the frequent interruptions can serve him in the same way. "I do it for a reason and sometimes I do it too much," he said. Often "it is in the interest of pacing. And secondly, I'm passionate and I care about the conversation.... After I read that somewhere and realized that I should take a look, I did, and I'm more conscious of it now than I was in the past. But I don't think you should ever lose your spontaneity, you should never lose what it is that defines you.... Because all of a sudden you'll become homogeneous and bland and without distinction."

"He does everything instinctively, and he believes that's the road to salvation," says one man who knows Rose. But instinct isn't always enough on the air (for instance, Rose has never mastered the art of reading a TelePrompTer). And off the air, there's a lot it can't compensate for.

I told Rose that his interpersonal skills had been called into question. "I'm sure that at times I can be difficult, demanding," he responded. Then he stopped, to change the tape in his recorder. "I should have therapy—see, this is good for me," he remarked breezily, then went on: "I just think I genuinely care about people. . .and that's across the board."

As for the way he's handled his celebrity, "Well, I haven't paid much attention to it, that's correct," he said with a touch of annoyance. "I haven't managed my own persona. I have been very caught up." He also blamed his own naivete. "I'm just not very savvy about things like

that_I don't know. I didn't get any of

that when they passed it out."

I asked Frank Stanton, who has known Rose for 25 years, whether he thought Rose was naive. "I think that's a carryover from when he first came to New York," he answered. As for now, "he's too bright not to know what he is doing."

If Rose knows just what he's doing, why is he currently under siege? Is he just experiencing the kind of momentary media blip that comes with success? Or is he his own worst enemy? The naked quality of his desire to shine leaves even his supporters frustrated. "You can't be so palpably obvious," says an ambivalent friend. "What's

sad is that he doesn't realize his worth," says one admirer, who believes that this insecurity accounts for his relentless drive to impress the world with what he has accomplished and the company he keeps.

It's as if Charlie Rose the man keeps interrupting Charlie Rose the show. By the time I sat down with him, I had a folder stuffed with praise for his work. (Clive James: "As a talk-show host myself I enjoyed being his guest because I couldn't hear the wheels turning; usually I can." Philip Johnson: "the best interviewer in the world.") But Rose still felt compelled to read out to me bits and pieces from various reviews and profiles. "There are three people who refer to me as Gary Cooperish," he remarked, leafing through the clips. "Judy Miller said that I like women, that I treated women seriously. I do.

"I mean, if you look at the pieces about me. . .The [New Yorker] piece said, Look, this is one of the good guys. I mean, he's better than everybody else, that's the problem. I don't know if any of that's true."

It is true, but whether Rose is constitutionally capable of ceding some control and accepting his achievement gracefully is another matter. And if he did, would he lose what defines him: the frazzle, the passion, and the undercurrent of vulnerability? Trying to get at the heart of the Charlie Rose dilemma, Wendy Wasserstein reaches for a line from her play The Heidi Chronicles. Sometimes, she says, "what makes you a person is what keeps you from being a person."

And sometimes what keeps you from being a person is what makes you a star. Charlie Rose has a genius for shooting himself in the foot; he has an equal genius for creating excitement and interest in what he does. When I raised the subject of his romantic difficulties, he solemnly told me that "I have made it a practice, as you can discover from reading the clips, to never reflect on my personal life when asked about any particular relationship.

... Lives should not be made into soap operas. Because they are real lives, and real people, and real pain. None of this is fair to her or to me." And that was when, both tape recorders whirring, he declared his undying love for Amanda Burden. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now