Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

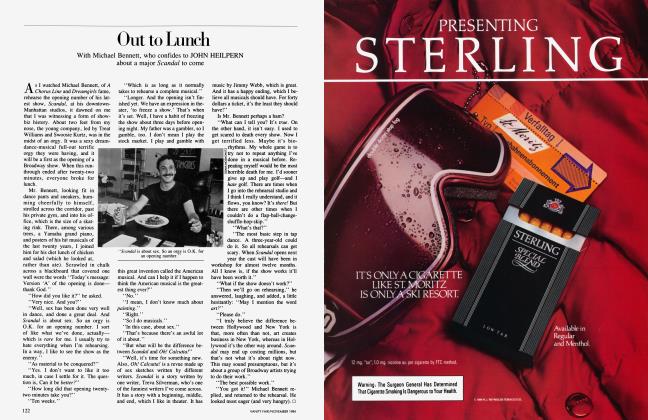

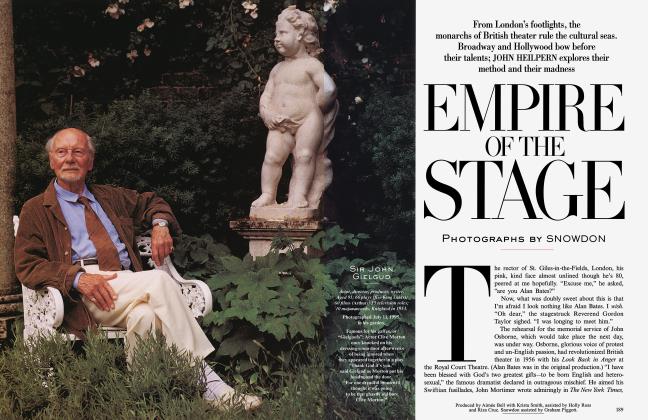

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDirector Roman Polanski, master of twisted psychodramas, has taken Ariel Dorfman's political thriller Death and the Maiden from stage to screen—and, JOHN HEILPERN reports to a new level of suspense—with Sigourney Weaver, Ben Kingsley, and Stuart Wilson as his stars

January 1995 John HeilpernDirector Roman Polanski, master of twisted psychodramas, has taken Ariel Dorfman's political thriller Death and the Maiden from stage to screen—and, JOHN HEILPERN reports to a new level of suspense—with Sigourney Weaver, Ben Kingsley, and Stuart Wilson as his stars

January 1995 John HeilpernOne night—a dark and stormy night, as with any traditional gothic thriller—in a remote part of a country that might be present-day Chile, a terrifying psychodrama shatters three lives.

A human-rights lawyer, Gerardo Escobar, newly appointed to investigate the unspeakable crimes of the previous regime, befriends a doctor, Roberto Miranda, and invites him into his home. Paulina, the lawyer's wife, tortured and raped 15 years earlier during the dictatorship, believes the doctor was her torturer. While her houseguest sleeps, she smashes him to the floor at gunpoint, stuffs her underwear into his mouth, binds him to a chair, and puts him on trial for his life.

"What if he's innocent?" pleads her husband.

"If he's innocent, then he's fucked," replies the wife, a psychotic or avenger in search of justice.

That's only the starting point of Ariel Dorfman's Death and the Maiden, and who better to direct the film version of the famous play than Roman Polanski? The controversial Polanski, who describes the public's perception of him as that of "an evil, profligate dwarf," is a master of twisted psychodramas whose best movies—Rosemary's Baby, Repulsion, Chinatown—relish a subversive menace, as if studying humanity as piranhas in a fishtank. Dorfman's political thriller seems made for him, with its potboiler-whodunit form and erotic suggestiveness, a neat subterfuge lulling us into the deeper, moral center. How does the victim of a monstrous crime forgive? How can a family man and lover of Schubert (whose "Death and the Maiden" provides the title) also be a sadist? And ultimately— in the fuel driving the tension that has us swaying as judge and jury—what if the accused is utterly innocent?

Roman Polanski's chilling sense of melodrama and fierce, jagged claustrophobia doesn't miss a trick.

The liquid dark eyes of the tremendous Ben Kingsley as the trapped doctor plead with us in terrified protest. Kingsley is so riveting, an epitome also of the banality of evil, that he could be the god of lies, whose deception is to confess: "I speak the truth." Sigourney Weaver as the fractured, damaged Paulina seizes a post-Alien challenge at last and rises to it with an emotional heat and freedom we haven't seen from this intelligent actress before—the victim now as exorcising victimizes taunting the bound Kingsley with an abuser's appetite. And semi-unknown British actor Stuart Wilson completes the trio wonderfully as the reasonable, spineless lawyer forced to defend the human rights of his wife's alleged torturer.

Polanski's chilling sense of melodrama and fierce, jagged claustrophobia doesn't miss a trick, but it's a relief that he transcends that downer movie credit "Adapted from the original stage play ..." This Death and the Maiden isn't merely and flatly a filmed play, and screenwriter and novelist Rafael Yglesias (who made his movie debut with Peter Weir's recent Fearless) has rid the original drama of its creakier moments. It's a tighter version, a no-exit morality thriller, which rescues it from the bad impression left by Mike Nichols's bland 1992 Broadway production, starring Glenn Close, Gene Hackman, and Richard Dreyfuss, that political torture, or an agonizing search for truth and grace, needs to be Hollywoodized.

Polanski's film material, Dorfman points out, belongs on the border of art and commerce, as does his own play. (Others also observe that Polanski's recent Bitter Moon, a sadomasochistic pseudo-comedy, belongs in outer space.) But violence and exile—the meat of Death and the Maiden—have always been a part of Polanski's troubled life. He is no stranger to the worst that life can come to, as Dorfman's drama in its turn is based on the dramatist's harrowing knowledge of General Pinochet's Chile. Polanski's pregnant wife, Sharon Tate, was killed in the Manson murders; his mother died in Auschwitz.

"As a child in Poland, of course I knew about arrest and torture," Polanski says from his home in Paris. "It was the reality. Torture was a fear greater than death. And if you've been tortured like Paulina, what does it make you? How do you go on? The piece is about the intense struggle for justice or revenge or reconciliation. "

The accused of Death and the Maiden, if guilty, is a fugitive from justice; Polanski fled justice, too. In 1978 he left America in the wake of the now notorious charge of unlawful sexual intercourse with a 13-year-old. "I consider myself a fugitive from injustice, if I may say so," he says, and reminds us that he was imprisoned in Los Angeles. "Everyone forgets what actually happened."

Perhaps. And who is innocent or guilty is at the disturbing heart of Death and the Maiden. Dorfman's original play tilted the evidence heavily against the doctor; Polanski's version is more ambiguous, and the better for it. "My deal with Ben Kingsley is that he's not guilty," Polanski explains. "He plays every moment so truthfully that even a confession seems true and false at the same time."

But does he think the doctor is guilty? "I don't know," Roman Polanski replies.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now