Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

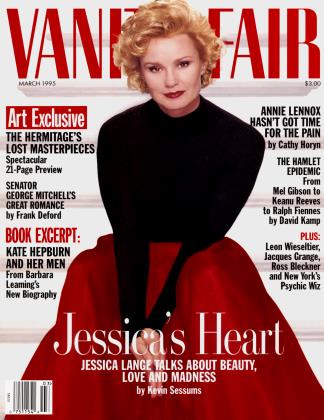

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowVANITY FAIR MARCH 1995

Fifty years ago some of the world's great art treasures disappeared behind the Iron Curtain. Confiscated from German collections by Joseph Stalins so-called trophy brigades at the end of World War II, this vast trove included paintings by Manet, Renoir, Gauguin, Cezanne, Picasso, and Matisse—along with countless rare books, manuscripts, and priceless archaeological finds. This month, after being locked away in Soviet vaults for half a century, the first of these long-believed-lost masterpieces go on display at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg—the former czarist palace that is truly as monumental as any of the paintings themselves. In this special 21-page preview, Vanity Fair presents a first-time look at the collection, while ROD MACLEISH tells the epic tale of how the cache was snatched from Nazi Germany and the historic maneuvering that resulted in one of the most remarkable art exhibitions of the 20th century.

THE ART AND THE GLORY

The Lost Masterpieces of the Hermitage

Art historians may rank the Hermitage exhibition as the

cold day in St. Petersburg; outside the Hermitage the sky is low, and sporadic gusts of wind send splatters of rain across the Neva River as it flows through the city between stone embankments. The vanquished past is everywhere here in this city, which, reckoned Peter the Great, claimed the lives of more than 100,000 serfs and indentured craftsmen during its construction.

Inside, the glow of imperial splendor radiates through the Winter Palace, the oldest of the great museum's five buildings. The home of Russia's czars until 1917, when the last of them— amiable, hapless Nicholas II—was overthrown, the palace is a monument to the art inside and to the self-indulgence of its former occupants.

The Winter Palace's 1,050 rooms, many lit by huge crystal chandeliers, are connected by grand, tapestry-lined hallways to 117 ornate staircases, and to reception chambers where malachite vases taller than a man stand among superb pictures and masterpieces of the furniture-maker's craft.

This month the palace's immense (12,716 square feet) Nikolayevsky Hall is the site of an extraordinary exhibition of 74 French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist pictures which have been unseen by the world for a halfcentury. The paintings are only part of a vast trove of canvases, archaeological finds, books, and rare manuscripts—two million objects in alltaken from museums, galleries, and German collections by Soviet-army trophy brigades, which raided the blasted ruins of Hitler's Germany after World War II. The booty was transported back to the U.S.S.R., where Stalin ordered it all locked away in museum vaults and libraries.

The exhibition will include paintings and pastels by Manet, Renoir, Pissarro, Gauguin, Cezanne, Picasso, and Matisse, as well as the works of other grand masters from the 19th and early 20th centuries. It is the most important show of French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in decades. Because of the fresh impact of these works, which were once presumed lost or destroyed in the war, art historians may ultimately rank the Hermitage exhibition as the most important of its genre since the New York Armory Show of 1913, where modern European painting was introduced to a somewhat hostile American public.

All paintings reproduced through arrangement with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., which will publish Hidden Treasures Revealed on March 30 in conjunction with the opening of the Hermitage exhibition.

most important of its genre since the Armory Show of 1913.

Mikhail Piotrovski, director of the Hermitage for the past two years, feels— as most Russians seem to feel—that the Soviet Union was justified in taking what was called Trophy Art from Germany in 1945. "I do not consider it a sin that art was taken away from Germany," Piotrovski says. "The sin was to conceal it from people for so long."

The Hermitage and the Russian Ministry of Culture first planned the Trophy Art exhibition in 1993. "This exhibition plan was made ... to show that—after all these years of secrets and isolation—we are now an open society, and want to be seen as part of the world community," Piotrovski told The Washington Post during a visit to the United States last fall.

Piotrovski is a slight, dark-haired man of 50 whose father was director of the Hermitage for 26 years before him. Piotrovski began his education in the museum when he was 10 years old. His precise manner turns passionate when he speaks of the Russo-German dispute over the $6.3 billion (German estimate) worth of art looted from the Soviet zone of Germany. "World War II was a very special war which had the goal of annihilation," Piotrovski says. "We are not on the same level as the Germans. They wanted to destroy our culture and our nation. We went to Germany only after the victory. . . . We had a lot of things destroyed, and it is for this that we must be morally compensated."

A lot of things destroyed.

That is one man's understatement of the extraordinary losses suffered by the Soviet Union between the Nazi invasion of June 1941 and the Germans' final retreat in 1944. The Trophy Art is a controversy left over from those terrible years, but its impact is increased by the complications of contemporary Russian politics. The presence of the art reminds Russians of the glories of the past, and inflames the country's despair over its reduced role in the world.

For decades, the Trophy Art hidden away in the U.S.S.R. was a state secret. Mikhail Piotrovski saw the German loot stored in his museum only when he became deputy director of the Hermitage in 1991. Although he is the current co-chairman of a negotiating commission composed of five German and five Russian museum directors, he is reluctant to discuss the status of the talks between the two countries. Russian museums are simply custodians of the German art, he says. "Whether some of it will eventually go back to Germany is not for us to decide," he says. "It is for the law to decide, the governments."

To make war is to take booty. Alexander the Great's armies plundered cities from Persia to the Indus River. Napoleon made off with German and Italian masterpieces for his family and the museums of France. But never has the looting of art been carried out on such an epic scale as that of the Nazis and, later, the retaliating armies of the Soviet Union.

It all began in the first, dark hours of June 22, 1941. Heavy bombers of the German Luftwaffe roared across the black sky over the western borders of the Soviet Union and began dumping their loads on every village, town, and city within their fuel range.

On the ground below, legions of German tanks rumbled their way into the U.S.S.R., blasting cannon fire at everything that got in their way.

Less than two years before, Germany and the Soviet Union had signed a nonaggression pact; the Soviet Union was unprepared for the German onslaught. While it scrambled to mobilize, the Nazi blitzkrieg hurtled deeper into Soviet territory. Within weeks the Germans had overrun most of Lithuania and Latvia, pushed to within 100 miles of Leningrad, captured Minsk, and begun penetrating the Ukraine.

Hitler's attack on the U.S.S.R. was driven by several motives. First and foremost, the Ftihrer wanted Lebensraum—living space—for the German nation. He ordered that all Russian Jews and Communists be shot the moment their ethnic or political identities were established. Slavs would be starved to death with the exception of the Russian-hating Ukrainians, who, some Nazi leaders believed, would be useful in helping to overthrow Stalin and kill Jews. Moscow and Leningrad were to be flattened so that any surviving Slavs, Jews, Communists, or other undesirables would be forced to move east to Siberia. After the Soviet Union had been conquered, German settlers would move into its drastically depopulated cities, towns, and countryside, making it all a part of the expanded fatherland.

A secondary, if less apocalyptic, Nazi objective was to strip the Soviet Union's museums, palaces, and galleries of art. Hitler appointed Dr. Hans Posse, a former director of Dresden's principal gallery, to gather art for a great museum that the Fuhrer planned to build in Linz, Austria, where he had spent part of his childhood. Other groups of art plunderers followed the German armies, some searching out masterpieces for Hitler's personal collection. (In The Rape of Europa, Lynn H. Nicholas describes the activities of the German art plunderers in full detail.)

Of all the Soviet Union's museums, the Hermitage was the prize most eagerly anticipated by Germany's official art thieves.

It had been emptied twice before—during Napoleon's invasion of imperial Russia in 1812 and at the onset of World War I. As the Wehrmacht fought its way toward Leningrad in the summer of 1941, the Hermitage's staff and a corps of volunteers packed and crated the most valuable of the museum's two and a half million objects—priceless paintings, porcelain, medals, glass, coins, imperial jewelry, and furniture. As the Luftwaffe strafed and bombed, two trainloads of Hermitage treasures were taken from the city. Their destinations were so secret that even the engineers weren't told where they were going until they were well en route. Before a third train could leave, the Germans completely surrounded Leningrad and a siege of nearly 900 days began. During those 30 terrible months the Hermitage was hit by bombs and artillery shells 32 times.

The Germans never captured Moscow or Leningrad. What remained in the Hermitage and the Soviet capital's Pushkin and other museums was thus spared plundering by the Nazis. But in other cities—Kiev, Minsk, Kharkov, Smolensk, Novgorod—as well as in many czarist-era palaces converted by the Communists into museums, thousands upon thousands of paintings, items of furniture, icons, tapestries, sets of silver, china, sculptures, books, and archives were ripped off walls, out of libraries and showcases, and sent to Germany by train and truck. What the Nazis didn't want was often burned, drenched with water, or simply trampled underfoot into splinters, rags, and muddy clots.

Grand estates around Leningrad were looted, then burned or blown up. The chapel of Catherine the Great's summer palace in the village of Pushkin was used by the Germans as a motorcycle garage.

Hitler had expected the Soviet Union to capitulate before the end of 1941, but in 1943 the tide of the war turned. When one Nazi army, the Sixth, surrendered at Stalingrad, the German troops were driven west and wreaked havoc as they went.

By January 1945, Soviet armies were swarming across eastern Germany while the Western Allies fought their way into the western two-thirds of the country. The final attack on Berlin began. In retaliation for what the Russians had suffered at Leningrad and Stalingrad, Soviet troops bombed and blasted the old German capital with special relish. As Stalin's armies entered Berlin, Hitler committed suicide on April 30. The war ended on May 8, 1945.

In the Soviet zone of Germany, the plundering process went into reverse.

After the Allies gained air superiority in 1944, the Germans built climatecontrolled mine shafts and dug bunkers and tunnels, which were used to hide and protect objects from their museums as well as the art they had looted from other countries. In 1945 the Soviet army's trophy brigades found the underground hiding places and a cache of art hidden beneath a tower at the Berlin zoo.

Soviet general Vasily Chuikov took over the estate of a wealthy German industrialist named Otto Krebs as a regional command headquarters. Ninety-eight French Impressionist and PostImpressionist paintings were discovered in a safe room. A large number of pictures in the current Hermitage exhibition come from the Krebs collection. But little has been discovered about Krebs himself.

Through the rest of 1945 and 1946, Stalin's trophy brigades plundered museums and private collections in Berlin, Dresden, Gotha, Weimar, and other cities in the Soviet zone of Germany. Paintings, sculptures, books, rare manuscripts, architectural pieces, figurines in terracotta, drawings, prints, and gems were packed onto trains, transported back to the Soviet Union, and hidden away in museums, libraries, and vaults.

"I do not consider it a sin that art was taken away from Germany, the sin was to conceal it from people for so long."

With a great whoop of propaganda in the mid-1950s, Moscow announced that it was returning more than a million objects—including the contents of the Dresden museum—to East Germany. The motive was political; East Germany was being rewarded for supporting Soviet policy.

Aside from that charade, the rest of the German Trophy Art was kept hidden away in Soviet museums and libraries. The few museum directors and librarians who knew about the German loot stored in their vaults kept their mouths shut.

No one can pretend to understand the workings of Stalin's mind, and the reasons for the secrecy surrounding the Trophy Art have long been the subject of political speculation. One fascinating theory has its origins in the late 1920s and early 1930s; during those years Stalin ordered art sold to raise hard currency. A former secretary of the U.S. Treasury, Andrew Mellon, bought 21 old masters, including Raphael's stunning Alba Madonna, for only $7 million. They later became part of the founding collection of Washington's National Gallery of Art.

Those sales were—and are—considered a national disgrace in Russia, even though such sentiments couldn't be publicly voiced during or even after Stalin's time. These controversial sales may help explain why the Trophy Art completely disappeared from public view, its very existence denied by the Soviet Union. Had museum records been produced for restitution talks with the Germans or any other reason, they might have revealed the full extent of Stalin's plundering of his own country's museums.

At any rate, most scholars and art historians in the West accepted that masterpieces which could no longer be accounted for had perished in Allied bombing raids on Germany during the last, fiery weeks of the war.

Riding a train through the pale autumn sunlight of the Rhine Valley from Frankfurt to Bonn last October, I remembered a question that a German diplomat friend had posed during my years as a foreign correspondent: "How long does a nation have to repent?"

If there is an answer at all it has to do with how long the nation feels the consequences of its sin—how long, in other words, it knows that somewhere, in some way, it is not yet forgiven. Russia has not yet forgiven Germany for the invasion of 1941. Dreadful memories still linger in the former Soviet Union—of the sieges of Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) and Stalingrad (now Volgograd). For Germany the return of its looted art would symbolize a final act of forgiveness by the Russians, a closing of the last chapter of World War II.

At the German Foreign Ministry, diplomats say that they consider relations with Russia excellent. Germany has donated more than 90 billion marks for Russian reform—for the salaries of the Russian troops stationed on the soil of what used to be East Germany and for other aspects of the process of building a new Russia.

"We consider the art question a part of overall German-Russian relations," said Markus Ederer, a Foreign Ministry specialist on the issue. "The Russians want to separate it out, treat it as an unrelated question."

The question of restitution of the Trophy Art first came up in 1989, during negotiations for a General Relations Treaty between the Soviet Union and Germany. Diplomatic negotiations have continued sporadically. Piotrovski's commission of German and Russian museum directors meets regularly to discuss the condition of the Trophy Art objects and to arrange for German specialists to see them periodically. The museum directors don't negotiate the return of anything to Germany. "For both governments the art itself is unimportant," said a German art historian who is an adviser to his government and wishes to remain anonymous. "It is a symbol of two national psychologies."

The Germans insist that the law is on their side; a treaty with the Russians signed in 1900 calls for the return of all looted art. Article 46 of the rules of land warfare drawn up at the Hague Convention of 1907 states that "private property will not be confiscated." Both Germany and Russia are signatories to the 1907 rules. The Germans regard them as binding law, the Russians as antique international statutes.

Germany doesn't want to lean too heavily on the Russians over the art issue. The fear in Bonn is that if severely pressured the Russians will break off negotiations forever. The legal discussions are conducted delicately. "We do not present claims to each other," one German diplomat said. "Rather, we submit lists of each side's losses." Using this elaborately polite formula, the Germans claim they are missing 200,000 art and archaeological objects, two million books, including two Gutenberg Bibles worth nearly $20 million each, and "three kilometers" of archives.

The Russians have removed blownup palaces, museums, and residences from their catalogue of losses at the hands of the Germans. They have submitted a list of nearly 40,000 items that disappeared between the Nazis' first assault on the Soviet Union and the final German retreat.

German analysts are aware of the impassioned controversy in Russia over the Trophy Art issue. "They feel chagrined by their loss of empire," a Foreign Ministry official said. "Their self-esteem is so low that they question whether they should give back the art, which is the last token of their victory in 1945." One German art historian I spoke to applied the same logic of psychological determinism to his own nation's position on the art issue; he noted that the paintings and other objects aren't as important as the war of 50 years ago in which they changed hands.

The intergovernmental negotiations are intermittent, and there has been very little give on either side. On the day I was conducting interviews in Bonn last October, German scholars visiting Moscow were, for the first time since 1945, being shown the so-called Trojan Gold, a collection of gold armor and artifacts excavated from ancient cities by the 19th-century amateur archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann. A businessman with a passion for Homer, Schliemann discovered the ruins of Troy in 1871. Soviet troops found Schliemann's treasure in the ruins of Berlin. It was taken back to Moscow and secreted in the vaults of the Pushkin museum.

For a half-century the Soviets and then the Russians denied they had Schliemann's gold artifacts. Last fall they finally admitted the gold was in Moscow.

Thirty-six hours later I was sitting in the office of Dr. Piotrovski. During our first meeting in St. Petersburg, the director of the Hermitage had not been disposed to talk about negotiations with Germany. He had been irritated by an article in an American newsmagazine which implied that the Hermitage was staging the show of French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists to finance repair work on its disintegrating buildings.

"We are charging nothing for this special exhibition," Piotrovski said. "Anybody who pays the entrance fee to the museum can go see the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists at no extra cost."

Between 600,000 and 700,000 people visit the Hermitage each year. "Depending on the weather, conditions in the country, and other factors, we expect up to one-third more than usual in 1995," Piotrovski said.

I asked him about the real, versus the rumored, condition of the museum.

He laughed. "It's about as bad as the Metropolitan in New York. They need $300 million also. There's nothing catastrophic, but if we don't begin repairs now, there will be a catastrophe in 10 years."

The Winter Palace was built in the 1750s for Czarina Elizabeth, Peter the Great's daughter. As Catherine the Great—who ruled from 1762 to 1796—began to buy pictures and the collection overflowed the wall space in the Winter Palace, she had new galleries added on.

In the 18th century, many great European estates included ornate little buildings where servants couldn't overhear gossip at small, intimate gatherings and dinner parties. They were known as "hermitages." Catherine gave the name to her first new galleries.

These and the buildings added by her successors—most notably the tyrannical Nicholas I (who ruled from 1825 to 1855)—are awesomely grand. Some were explicitly designed for particular displays: there are walls of rose and green marble for galleries exhibiting white Roman statuary; there are immense, high-ceilinged galleries for the huge canvases of the 17thand 18th-century Italian painters.

Some of the additions to the Winter Palace were erected on the foundations of older structures, which, in the marshy terrain of the Neva estuary, have shifted during nearly two and a half centuries. There are cracks in the walls of some galleries; water damage is evident in others. Sunlight falls on many paintings; some exhibition rooms are too dry and need airconditioning.

There is a desperate shortage of storage space. A new building for the Hermitage was being constructed across the river by the Ministry of Culture, but money ran out. The building stands unfinished—and badly needed.

Money is in desperately short supply. Mikhail Piotrovski says he spends at least a third of his time raising funds for the museum—a good deal of it in complex negotiations with the Russian Ministry of Culture, which approves the Hermitage's budget, and the Ministry of Finance, which is supposed to provide the approved cash but often can't.

UNESCO is helping to organize "Friends of the Hermitage" associations in several countries, including the United States. Western European and American corporations give cash, donate equipment, and provide services on a partially pro bono basis. But it is never enough.

The negotiations between Russia and Germany are a tea dance compared with the political uproar in Russia itself over the issue. "It is almost impossible to have a political discussion about the Trophy Art," said Andrei Yurkov, deputy editor of the St. Petersburg News, the paper which broke the story of the French Impressionist and PostImpressionist exhibition. (Artnews broke the story of the existence of the Trophy Art in 1991.)

Echoing the German foreign office's view of his country, Yurkov said that Russia feels humiliated, sneered at. Japan is pressing its claims to the Kuril Islands off Russia's Pacific coast; Estonia wants vast stretches of western Russia. "Our principal exports are raw materials," Yurkov added, "which is our main national treasure. Russian know-how is degraded."

In such an emotional climate, Russian nationalism, which anesthetizes humiliation, runs rampant. Last June the minister of culture, Evgeny Sidorov, was burned in effigy during two days of demonstrations by right-wing mobs in Moscow. He was suspected of not being tough enough on the art question.

"Restitution" is becoming a dirty word in discussions about the German-art issue. "It implies we did something wrong," said Eugenia Makarova, a senior librarian at the Hermitage, "something we should make amends for. We didn't."

The Russian government's Institute of State and Law—a division of the Academy of Sciences—has issued a document declaring that the seizure of German treasures in 1945 was legal because everybody else was doing it. Besides, the institute added, the four-power Allied Control Council recognized the issue of compensation.

If the Germans want their art given back as a symbol of World War II's final end—and an end to penance—millions of Russians want their government to keep the Trophy Art so that the war will never be forgotten. Possessed by the greatest identity crisis of its history, Russia needs national reassurance. As long as it keeps the Trophy Art, the triumphant ghost of the war in which it suffered, persevered, and finally emerged victorious will linger, a specter of Russian greatness.

On the afternoon I went to the Hermitage to say good-bye to Dr. Piotrovski, he turned, at last, to the tangled, emotional, and seemingly intractable standoff between Russia and Germany. "It's not easy," he said. "If we do a lot of talking and discussion, I think we will find a solution which will be good for all sides and many generations. I think it is possible, but it will take a long time."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now