Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEND OF EXILE

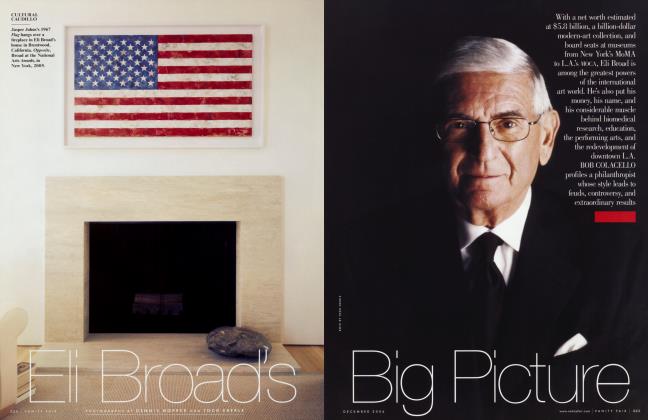

Robert Wilson, the recherché American creator-director of minimalist masterpieces such as Einstein on the Beach, is celebrated in Paris and Berlin, with devoted patrons including Pierre Bergé and São Schlumberger. BOB COLACELLO profiles the exile from Waco, Texas, as Wilson returns home with a new production: a Hamlet in which he takes on all the roles

BOB COLACELLO

"We had the Persian army to help us 5,000 troops building scenery and 2,000 performing with us."

One afternoon last spring, at Harry's Bar in Florence, I listened as two international writers pondered a curious conundrum: Why is Robert Wilson, the most celebrated creator and director of theater and opera in Europe today, so uncelebrated in his own country?

"I think his Madame Butterfly at the Opera Bastille was the best one ever done," said Edmund White, the American novelist and Jean Genet biographer, who lives in Paris.

"A woman who is hard as nails told me she cried," said Gregor von Rezzori, the Romanian-born, Tuscany-based writer probably best known for his novel Memoirs of an Anti-Semite.

"The problem with Bob is that he is a playwright who doesn't really write," White said. Wilson's early original works, such as his 1973, 12-hour The Life and Times of Joseph Stalin, had no dialogue and no plot, and even his newer productions with texts are uncompromisingly antinarrative.

Perhaps, I suggested, Wilson's works are too unclassifiable for Americans, who like to pigeonhole everything. Are they plays?

Modern-dance works? Performance-art operas? Among the "crucial, Zeitgeist-deflning artistic creations of the Western world," as The Washington Post's Alan Kriegsman suggested in a review of Wilson's most famous work, Einstein on the Beach? Or are they, as Wilson's detractors maintain, just too long, too pretentious, too expensive, too perverse—elaborate private jokes that only he gets? ("Smile at the wrong times" is a typical Wilson direction to actors.)

"Bob's work is Gesamtkunst-

wer/c—an idea of Wagner's— the total abstraction of theater," von Rezzori said.

"He starts with the decor, like Meyerhold did in Russia in the 20s," White said. "He's also related to Artaud and the Theater of Cruelty."

"Very much so," said von Rezzori.

We were on our way to the Teatro della Pergola to watch Wilson rehearse a pair of one-act operas based on Japanese Noh plays—Hanjo, "a little lesbian love story," as one Wilson follower put it, by Yukio Mishima, with music and libretto by Marcello Panni, and Hagoromo, a more traditional piece, with music by Jo Kondo—which were being presented at the 57th May Music Festival in Florence, and which would go on to be honored by Italian critics for best direction and set design of 1994. Since 1984, when the Los Angeles Olympic Arts Festival canceled his $2.6 million dusk-to-dawn epic, the CIVIL warS: a tree is best measured when it is down, sections of which had been staged previously in Rotterdam, Cologne, Paris, and Rome, Wilson has worked primarily in Europe, mainly transforming other people's operas and plays into his own, unmistakably minimalist yet grandiose visions. These have ranged from Richard Strauss's Salome, starring Montserrat Caballe, with costumes by Gianni Versace, at La Scala in Milan in 1987, to Virginia Woolf's Orlando, starring Isabelle Huppert, which was extended by popular demand from 30 to 60 performances at the Odeon theater in Paris last summer. His 1991 production of Mozart's The Magic Flute has been revived four times at the Opera Bastille.

And yet only a handful of Wilson works have been seen in New York in the last decade, the most recent being The Black Rider: The Casting of the Magic Bullets, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) in 1993. This relatively short musicaltheater pastiche, with hummable music by Tom Waits and an amusing text by William Burroughs, was created, however, at the Thalia Theater in Hamburg, where it ran for two seasons, and went on to Vienna, Paris, Amsterdam, Berlin, Genoa, and Seville before traveling to BAM for a limited engagement of 10 sold-out performances.

New York Times critic John Rockwell, a longtime Wilson loyalist, had also trekked to Florence to see the Noh operas. He later recalled a con-

versation he had with Wilson there: "Bob said he was feeling a bit burned out in terms of reinterpreting classical works. He was tired of wandering around the European cultural diaspora. He said he was actively pursuing different kinds of work. And he also said he wanted to act."

This month America's most misunderstood genius is coming home to the state of his birth, Texas, and making sure that everybody knows it, by taking on the greatest and most difficult role of all, Hamlet. What's more, Wilson being Wilson, he's portraying not only the Prince of Denmark but also King Claudius, Queen Gertrude, Ophelia, Laertes, Polonius, and Horatio—and designing the sets as well. "It's done as a series of flashbacks, which start seconds before Hamlet dies," Wilson told me. "All the speeches of the various characters are included. It's Shakespeare's text, but I've rearranged it."

HAMLET a monologue, which will run between 90 minutes and two hours without an intermission, opens on May 24 at the Alley Theatre in Houston. It will also be in Lincoln Center's Serious Fun! festival in July. In November the Martha Graham Dance Company is scheduled to premiere Wilson's evocation of its legendary founder at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. In January the Houston Grand Opera will mount his production of Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thomson's 1934 work, Four Saints in Three Acts, which will also be included next summer in a new international arts festival at Lincoln Center, organized by John Rockwell.

If a Wilson revival in America is at hand, it seems auspicious that it should involve two of his idols: Martha Graham, whose dictum "All theater is dance" Wilson cites constantly, and Gertrude Stein, whose way with words was as original and maddening as his.

In a sense Graham, the sui generis American artist, and Stein, the quintessential American expatriate avant-gardist, are Wilson's spiritual and aesthetic godmothers, the two sides of his persona and oeuvre. For all of his highbrow Continental airs, Wilson's story is pure Americana, and the unnerving silences, wide-open spaces, and slow, straightened movements of his stagecraft can be read as pictures of where he came from.

'I was born in Waco, Texas, in 1941. It's very conservative. It has the largest Baptist institution in the world, Baylor University. When I was growing up, it was a sin to go to the theater. It was a sin if a woman wore pants. There was a prayer box in school, and if you saw someone sinning, you could put their name in the prayer box, and on Fridays everyone would pray for those people whose names were in the prayer box. Smoking a cigarette was sinning, too." He lit another Parliament before ordering lunch in Florence's Hotel Excelsior. "I couldn't wait to get out."

At 17, Wilson was cured of a severe stammer with the help of a local dance instructor named Bird Hoffman, who encouraged his interest in the performance arts. But to please his father, a lawyer who later became the Waco city manager, he spent the next three years studying business administration at the University of Texas in Austin. In 1962, just a few credits short of graduation, he dropped out, moved to New York, and plunged into the overlapping worlds of art, theater, dance, film, poetry, and happenings. He soaked up the classical ballets of George Balanchine and the avant-garde works of Merce Cunningham and John Cage. He studied interior design at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and worked with choreographers Alwin Nikolais, Meredith Monk, and Kenneth King as a handyman, set designer, and performer. He had a nervous breakdown, tried to kill himself, and was put into a mental institution for several months. In 1968 he founded his own experimental theater company, the Byrd Hoffman School of Byrds, named after his Waco teacher, and installed it in his SoHo loft building, which evolved into an intellectual version of the Warhol Factory. "I had open houses every Thursday that went on all night," Wilson told me. "There were three floors: one for dancing, one for eating, and one for discussions."

All through this period, Wilson also taught brain-damaged and disturbed children in Harlem and New Jersey. One day in 1968, in Summit, New Jersey, Wilson remembered, "I saw a policeman about to hit a child over the head with a club. I recognized that the sounds the child was making were those of a deaf person. He was a 13-yearold black deaf-mute child, and he was going to be locked up in a delinquent home. They said he was uneducable. Eventually I went to court and became a legal guardian, and he lived with me. It became apparent after a short while that he thought in terms of visual signs and signals. He made drawings of things I couldn't see because I was preoccupied with words. My first major works in theater were written in collaboration with this young man: Raymond Andrews."

"Bob s this incredible person who has annexed the most interesting rich people in the world."

Wilson's first complete play, The King of Spain, ran for two nights in 1969 and consisted of one scene, about two hours long, of various people—including Wilson and Andrews—coming and going in a Victorian drawing room, the back wall of which was slit open to reveal a sandy landscape. The highlight came near the end when 30-foot-high white cat's legs walked across the stage slowly. "It was very different from anything happening in theater at that time in New York," Wilson told me. "Living Theatre, La Mama— that was all too expressive for me. The King of Spain was very formal, very carefully lit. There were no words. There was a tea cart, and sometimes it would shake, and you'd get little sounds like that."

Then came The Life and Times of Sigmund Freud and Deaf man Glance, both of which were also stylized and lengthy. In 1971, Wilson was invited to the Festival Mondial in Nancy, France, by its director, Jack Lang, the future minister of culture. Wilson helped cover his troupe's trip by selling five drawings Andy Warhol had given him to Dominique de Menil, the Houston art collector. In Nancy, he combined Freud and Deafman into a single seven-hour work, which caused such a sensation that the couturier Pierre Cardin moved it to Paris for a six-week run at the Theatre de la Musique. "The miracle was produced, the one we were waiting for," wrote Louis Aragon in an open letter published in a Communist journal, to his fellow Surrealist Andre Breton, who had died five years earlier. "You would have loved it as I did, to the point of madness." Eugene Ionesco compared Wilson to Samuel Beckett, and other reviewers invoked the names of the Douanier Rousseau, Rene Magritte, Paul Delvaux, Salvador Dali, and Marcel Duchamp to describe Wilson's unexpected imagery and otherworldly lighting. Charlie Chaplin went back a second time, and Empress Farah Diba was entranced.

"She asked me to go to Iran and do something," Wilson told me. "I did a seven-day play." KA MOUNTAIN AND GUARDenia TERRACE: "a story about a family and some people changing" was presented as one continuous performance lasting 168 hours at the 1972 Shiraz-Persepolis Festival of the Arts. "It was structured a little bit like television," Wilson explained. "There were seven hills, and by the seventh day we had activities happening on all of them. We had the Persian army to help us, 5,000 troops building the scenery and 2,000 troops performing with us. There were 500 actors. We painted one hill white and we had a big dinosaur at the top, and we had groups of actors and troops stationed on the other hills, chanting the word 'dinosaur.' At the final hour, we blew up the top of the white hill with dynamite—like this snowcapped mountain erupting."

In 1973, as Wilson prepared to go onstage—he acted in all his early works—for the premiere of The Life and Times of Joseph Stalin at BAM, there was a knock on his dressing-room door. It was a friend of a friend with her 14-year-old autistic son, Christopher Knowles. Wilson recalled that a professor at Pratt had given him a tape made by the boy, and he asked Knowles if he'd like to be in the play that night. Wilson led Knowles onstage by the hand, and together they recited the words on the tape from memory: "Em Em Em Emily likes the TV. Because Emily watches the TV. Because Emily likes the TV. Because she likes Bugs Bunny. Because she likes the Flintstones. Because she watches it. Em Em Em Emily likes the TV."

Continued on page 165

Continued from page 135

And so text blossomed in Wilson's work—and the repressed emotion at the core of his cold minimalism became a little more touching. His next important pieces, A Letter for Queen Victoria, The $ Value of Man, and Einstein on the Beach, all included texts by Christopher Knowles. Einstein, a four-and-a-half-hour opera in four acts without an intermission, with music and lyrics by Philip Glass, is considered the Don Giovanni of minimalism. It is one of only five Wilson works which have been commercially recorded, and by far the most often revived. Commissioned in 1976 by the then French cultural minister, Michel Guy, who gave Wilson and Glass a $250,000 grant to stage it at the Avignon Festival and the Festival d'Automne in Paris, it was also presented at the Venice Biennale of that year and in Belgrade, Brussels, Hamburg, Rotterdam, and Amsterdam. Wilson and Glass were so determined that it be seen in New York that they produced it themselves for two nights at the Metropolitan Opera, which were sold out, but they still ended up $150,000 in debt.

Vowing never to produce his own work again, Wilson fell back into the generous embrace of Europe's state-supported theaters, opera houses, and cultural festivals. His next two large works, Death Destruction and Detroit, inspired by a news photograph of Rudolf Hess in Spandau prison on his 82nd birthday, and Edison, about the inventor of one of Wilson's favorite stage images, the lightbulb, were produced by Berlin's Schaubiihne and Lyons's Theatre National Populaire, respectively. In both pieces, Wilson used texts researched by Maita di Niscemi from historical and literary sources, beginning an ongoing collaboration with the halfItalian, half-American writer-principessa. "I'm doing Prometheus in Greece with Bob in the summer of '96," di Niscemi told me. "We're going to use Aeschylus as the center act. The first act will be almost silent, and the third act will be a balletic interpretation of Aristophanes. It's going to be long."

'Bob's the closest thing to Diaghilev we have," says the New York art collector Barbara Jakobson. "This incredible person who has annexed the most interesting rich people in the world." Among the annexed: Parisian hostess Sao Schlumberger, whose late husband, oilequipment magnate Pierre Schlumberger, partly financed Einstein; their daughter, Victoire Schlumberger, who helped make the sets for Wilson's production of Dostoyevsky's The Meek Girl in Paris last year; Christophe de Menil, a New York cousin of the Schlumbergers' and one of Dominique de Menil's daughters, who designed many of the costumes for the CIVIL warS; Gabriele Henkel, of the German chemicals fortune; Park Avenue's Frederick and Isabel Eberstadt, who appeared in Edison; Ethel de Croisset, an American grande dame living in Paris; and Pierre Berge, the chairman of Yves Saint Laurent and until recently the president of the Paris Opera.

Many of Wilson's devotees collect his sculpture and drawings, which have been shown in galleries since the mid-70s and which currently fetch from $4,500 to $80,000 at the Paula Cooper Gallery in New York. The sculptures are mostly limited editions of the furniture from his theater pieces: the lead Stalin Chairs, the Einstein Chairs of galvanized pipe, the chrome Rudolf Hess Beach Chairs. Wilson was given major exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Pompidou Center in Paris in 1991, and at the 1993 Venice Biennale he was awarded the Golden Lion for sculpture for his installation Memory/Loss. "There was controversy over giving the prize to me as a sculptor," Wilson complained. "Michael Kimmelman in The New York Times called it a room full of mud."

Continued on page 168

Continued from page 165

The critics notwithstanding, Wilson is no longer creatively homeless in America. Since 1991 he has been an associate artist, along with Edward Albee, at Houston's Alley Theatre. His First production, in cooperation with Robert Brustein's American Repertory Theatre at Harvard, was Ibsen's When We Dead Awaken. Then came Buchner's Danton's Death, and now le tout Houston awaits his Hamlet. He also has a niche at the Houston Grand Opera, which co-produced Wilson's resoundingly successful staging of Parsifal in 1991, and is now preparing Four Saints in Three Acts. And this will be Wilson's fourth summer in residence at his Watermill Center on Long Island, a 30,000square-foot former Western Union research laboratory which he is converting to rehearsal spaces and dormitories for visiting students to take part in workshops for his future productions.

That doesn't mean that his exile is over, however. In August he will fly to Salzburg to stage Bluebeard's Castle and Erwartung, the latter starring his pet diva, Jessye Norman. When I called him in Munich in February, he rattled off an overwhelming itinerary: "I just came from Marseilles, where I was making glass sculptures and vases. Tomorrow I'm going to Hamburg to see Lou Reed about a piece tentatively called Time Rocker. It opens in June '96. And I just came from China, where I was doing a workshop with students at the Shanghai Theatre Academy. Oh, and I've designed a pen for Montblanc, so I'm meeting with them in Hamburg, too. It's black, and it has a silver cap—almost an organic form, like a flame—which makes it nice to hold in your hand."

Only Robert Wilson would see Fire as tactile.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now