Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBattle of the Bluebloods

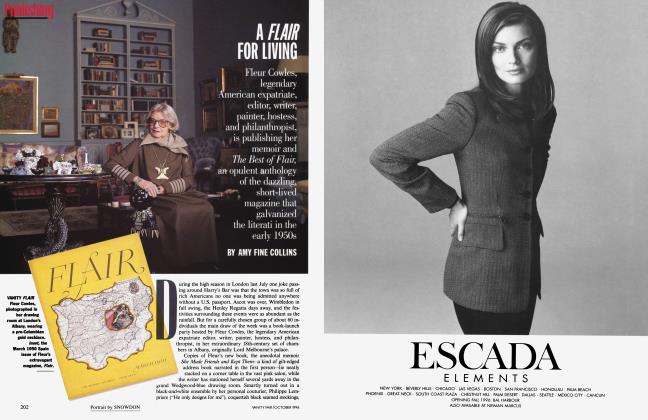

Massachusetts's tall, handsome, wealthy, patrician Democratic senator, John Kerry, is being challenged by the state's tall, handsome, wealthy, patrician Republican governor, William Weld. ALEX SHOUMATOFF, who attended St. Paul's with Kerry and Harvard with Weld, handicaps what will be one of November's most closely watched elections

ALEX SHOUMATOFF

The venue of the first of the seven debates that Governor William Floyd Weld and Senator John Forbes Kerry have agreed to couldn't be more momentous: Boston's 18thcentury Faneuil Hall, the scene of much of the fiery oratory that sparked the Revolution. Politics is the real spectator sport in Massachusetts, and this "clash of the titans," as the local press is hyping it, promises to be high theater. Weld, the Republican, wants to go to Washington, he had told me a few days before, "to apply the same thing I've been doing here"—his maverick brand of fiscal conservatism and social libertarianism—"on a different canvas," so he is making a move on Kerry's seat. But Kerry, the Democrat, isn't about to give it up. He wants six more years to advocate for the disadvantaged, safeguard the environment, fight crime and the Republican congressional agenda—to demonstrate that government has a higher purpose than simply to reduce itself, a role to play in bettering people's lives. The cream of their generation and their parties, both candidates are highly articulate, Ivy League-educated, and of New England blueblood stock. Weld is 51, Kerry almost two years older. Both stand an imposing six feet four, both got their starts fighting corruption, both have terrific wives. This is the year's hottest Senate race. Whoever wins could have a shot at the presidency in 2000.

Sitting in the press gallery, I am basking in reflected glory. Those are my old schoolmates down there, waiting to tear into each other at their respective lecterns. I was at prep school with Kerry, and at Harvard with Weld. Red-haired, pink-complected Weld is known affectionately as Big Red in this overwhelmingly Democratic state, which re-elected him as governor two years ago by an astounding 71 percent. He is wearing his characteristic mask—a laid-back look, vaguely crocodilian—but with a mischievous twinkle in his eyes, which surf the audience, classifying friend and foe. I've finally realized whom the public Weld reminds me of: Bill Murray. He has downsized himself to 215 pounds, the adrenaline of the campaign causing him to shed 10 pounds in a month, he explained to me. Kerry is the same lanky 180something he was in college. The differences between him and Weld are not only ideological but also metabolic. Kerry is a driven, hyperkinetic type A; Weld describes himself as type Z. Weld wears rumpled off-the-rack suits; Kerry is elegantly tailored and coiffed—craggy-faced, lantern-jawed, bushy-browed, he looks so classically senatorial you could put him in a toga or on a coin. Some find him too pretty, a cross between Hugh Grant and the late Fred Gwynne. His nickname over at The Boston Globe is Blow-Dry Kerry because of his Kennedy-esque salt-and-pepper hair. At this year's St. Patrick's Day breakfast hosted by legendary South Boston political boss Billy Bulger, where the candidates poked fun at each other with doggerel, Weld said Kerry "uses so much Aqua Net, he has his own personal hole in the ozone layer." Kerry is trying to shuck the perception that he's too formal and aloof, which may be why tonight he has loosened his tie ever so slightly, while Weld is hoping to demonstrate that he is not a phlegmatic dilettante and really cares.

The moderator of the debate is Charles Nesson, who turns out to be the Weld Professor of Law at Harvard. His chair was endowed in 1882 by the governor's ancestor William Fletcher Weld, who had a fleet of clipper ships; its first holder was Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Why are people poor? asks the respected newscaster Janet Wu. Kerry's answer ("Because the deck is really stacked against them") is more convincing than Weld's ("It's . .. partly the welfare culture we've had the last 40 years in this country"). As if poverty hasn't always existed. But this enables Weld to expand his spiel on why he has pared state assistance to the bone.

Kerry is asked about his muchballyhooed tour in Vietnam. And what about you, Governor? (Weld beat the draft with a bad back.) "We should all be grateful, and I am grateful, to Senator Kerry for his notable service in Vietnam," Weld says coolly.

Kerry wins hearty applause with a touche over Weld's favoring an eamedincome tax credit in place of increasing the minimum wage: "Governor, it is absolutely astonishing to me to hear you, the great purveyor of getting the government out of everything," advocate giving working men and women a federal handout for the rest of their lives instead of having their employers pay them a decent living wage.

Weld accuses Kerry of voting against mandatory sentencing for people who sell drugs to minors. "Governor, I don't know who does your research," snaps Kerry. "Maybe it's Oliver Stone." Kerry accuses Weld of squandering federal funds on yoga and meditation programs for prisoners instead of hiring more police.

The most emotional exchange and the deftest parry come over Kerry's opposing the death penalty, even for copkillers. Weld was expecting to set him up for a big fall. Conveniently, the mother of a slain cop, Michael Schiavina, is in the audience. Tell this woman why the life of the man who murdered her son is worth more than the life of her son, he says. Kerry says, "It's not worth more. .. . It's scum that ought to be thrown into jail for the rest of its life." Then he adds, "I know something about killing ['Nam again], I don't like killing, and I don't think the state honors life" by taking it.

Surprisingly, it is Kerry who connects and comes off as the sweet yet statesmanly candidate. Maybe this is the humanizing effect of his new wife, Teresa Heinz. John "has a lot of shells around him. ... He's had a lot of aloneness.... I think he was afraid love wouldn't happen again," she told the Globe. Weld, on the other hand, is uncharacteristically strident. Bill coming out fighting, launching into a shrill litany of Kerry's transgressions, is a side of him I haven't seen before. This is obviously a strategy cooked up by his handlers; he sleepwalked through his first debate, two years ago, against his gubernatorial challenger (and his wife's cousin), Mark Roosevelt. But Weld makes his points about how the state was more like Taxachusetts when he came in, and how he has cut taxes 11 times. The people who came in liking Weld still like him. Everyone agrees that it was a rousing debate, that these two political thoroughbreds in their prime did the Bay State proud. The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Boston Globe decline to declare a winner; but one columnist from the Boston Herald gives it to Kerry hands down.

The Welds got here in 1630 with "the shirt on their back and 2,000 pounds of gold."

The Weld clan and the Oyster Bay, Long Island, Roosevelts (descended from Teddy), of whom Bill's wife, Susan, is one, are the closest thing to aristocracy America can lay claim to. The Welds got here in the 1630s "with nothing but the shirt on their back and 2,000 pounds of gold," Bill said, joking. We were sitting in the governor's office in the majestic, gold-domed Massachusetts State House. "Now that you have your reporter's hat on, I'm going to keep you at arm's length," Bill had told me. I wouldn't be able to stay at the Welds' home in Cambridge, as I usually did when in town, because if the local press or the Kerry camp got wind of any special access or treatment, they would howl.

Welds were among the original benefactors of Harvard College. In gratitude for crushing the Pequot Indians, Welds were deeded by the Crown farmland in what is now West Roxbury. But Bill belongs to a Long Island branch of the family. His ancestor William Floyd, for whom he is named, had a farm in Mastic and was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. His great-grandfather Francis Minot Weld married the boss's daughter in the prestigious investment-banking firm of White Weld, which has since been subsumed by Merrill Lynch. Bill's father, David, was in the firm. He also bought 600 acres in Smithtown, on the eastern island, and was one of Suffolk County's backroom Republican bosses until he collapsed on the golf course from a heart attack in 1972. He was only 61. "My father went down swinging," Bill told me with grim humor.

David Weld was a passionate hunter and fisherman, and the property included the 130-acre Stump Pond, which was loaded with fish and, being right on the Atlantic flyway, with ducks in transit. Bill and his two older brothers spent their boyhoods on the pond, as did their first cousin John Nichols, the Taosbased novelist. Nichols recalls that it was "just a stupendous place to live, a halcyon universe, sort of like Nirvana. Uncle David transmitted a code of being in the outdoors, from gun safety to the wonders of conservation. The house was unostentatious. It had a room where you hung up the game. I remember meals of duck, with Uncle David carving at the table, after which the men repaired to one room for cigars, and the women to another. They were an incredibly generous family. Aunt Molly put me through the Loomis school." Weld remembered, "I wasn't conscious of our having money until I turned 21 and received a check from White Weld for $350,000."

"How much are you worth, anyway?" I felt rather awkward asking this, but every time Kerry's wife is mentioned in the papers, she is invariably identified as the heiress to a "fabulous ketchup fortune" of $760 million.

"Our family's net worth is four to five million," Bill replied. Peanuts.

Bill's brother Tim is a prominent heart specialist in New York. "Neither of you had to work, so where did the work ethic come from?" I asked.

"I enjoy working and earning money," Bill replied simply.

Having mutual friends who were completely paralyzed as a result of inherited money, I asked whether the realization that parental handouts were not necessarily doing the recipient a favor had influenced Bill's policy toward welfare. "No," he said.

"Not even subconsciously?" I pressed.

"I couldn't say." A slightly contemptuous look communicated that he found this a dumb question.

At Harvard, Weld seemed just a solid, regular guy. By 1965, LSD had made its way into the student body from Timothy Leary's Center for Personality Research.

It was readily available at Adams House, where Bill roomed, but he had nothing to do with it, or with the marijuana that was beginning to be smoked. "He was not at all disapproving, but he made it real clear that this was not his thing," his college friend Peter Brooks, now an art-history teacher in the Bay Area, recalls. Bill spent a lot of time at the Fly Club, one of the three undergraduate final clubs with social status. He could have joined the Porcellian, which is really stuffy upper-Brahmin, but he chose the Fly, which is more mainstream preppy. F.D.R. belonged. The upstairs is bristling with trophy heads.

At the Fly, Bill played lots of chess. People were puzzled how he could spend so much time there yet get all A's and be Phi Beta Kappa. Not to mention being active at the Hasty Pudding, where he is remembered for playing the female lead in a spoof of West Side Story.

Two days before it was due, Bill knocked off his senior thesis, which interpreted two lines of the Roman elegiac poet Sextus Propertius, and graduated summa cum laude, delivering the Latin speech at commencement. After a year at Oxford, he returned to Harvard for law school, from which he graduated in 1970.

"In the spring of 1969," Weld went on, "I was working in the statehouse in a three-piece suit while an anti-war rally was going down on the Common-music, beads, sandals—and I asked myself, What the hell am I doing here? But it paid off because the guy I was working for was offered a job on the Watergate case." In 1973, Weld was hired as associate minority counsel to the House Judiciary Committee, which was investigating Watergate. He worked with Hillary Clinton, who was a member of the impeachment inquiry staff, and has offered to be a character witness for her in the Whitewater investigation. (Some see this as an effort on Weld's part to make himself more attractive to women voters.)

In the early 1970s he dated Sandra Auchincloss, a willowy, classy blonde who had been one of the most attractive Radcliffe girls of our day and who recently died of cancer. He threw great parties in his loft on the Boston wharf and an annual bash at the aquarium. A woman who went to these parties recalled that, in keeping with the times, there were plenty of drugs, but Bill never partook. Often he would get the party started, then retire early. "He was like the center," she told me. "All these things happened around him, but there was something remote, larger-than-life about him. He was a Gatsbyan figure. I remember at my sister's wedding pushing him into the pool in his tails, and he pulled in me and all the other bridesmaids. There was a very boyish part of him, a real sense of mischievous fun."

Weld says Kerry "uses so much Aqua Net, he has his own hole in the ozone layer."

Bill's roommate at the time was his old Fly clubmate Mitchell Adams, one of the Adamses, as in John, John Quincy, Samuel, and Henry. (In front of Faneuil Hall there is a statue of Samuel Adams with the legend "He organized the Revolution." Last year, Weld compared Newt Gingrich to Samuel Adams and called "Newtie" his "ideological soul mate"—bouquets tossed to the House speaker, who is deeply unpopular in Massachusetts, that are now coming back to haunt Weld.) Mitchell Adams had been going through years of therapy, "the objective of which was to be straight. I was beginning to have boyfriends, but being very secretive about it. Bill didn't have a clue, and when my persuasion became apparent, his attitude was puzzlement that anyone would have a problem with it." Today, Adams is Weld's revenue commissioner. "We have the reputation of being the most advanced tax agency in the country," he told me. "We pioneered telephone filing. It takes eight minutes by Touch-Tone. You get your refund in three days." Adams has been living for 16 years with Kevin Smith, Weld's chief of staff. "In most cities of the world I would not be a happy camper," Adams reflected. He praises Weld's instinctive Yankee tolerance and decency. "Bill has a real strain of generosity that is very inconspicuous because he doesn't flaunt anything. He'll do something for me and I'll only learn about it by chance."

In 1975, Bill married Susan Roosevelt, the youngest of the three remarkable Roosevelt sisters of Oyster Bay, Long Island. Their father, Quentin, posted to Shanghai by the C.I.A., had died in a mysterious plane crash in 1948. Susu, as she is known to her family and friends, was a brilliant if not surprising choice. Susu is a Chinese legal historian who specializes in pre-Han and Han-dynasty graveyard texts from the sixth to the second century B.C. Bill is the first to admit that she is even smarter than he is. But you wouldn't know it, because she is completely unassuming, almost ascetic. An embodiment of what a friend calls "sparse Yankee stuff," Susu, her sister Sandy observes, "would never think of giving herself a luxury." To have your own jet and public-relations man and to talk publicly about your suffering, as Teresa Heinz does, are probably rather tacky in her book, although she would never say so. She is one of those rare individuals in whom graciousness and equipoise seem innate. With her quiet radiance and impish glee, she has been an unswerving moral rudder for Bill as he navigates his political career. Susu's smile seems to have grown of late, expanded to classic Rooseveltian proportions. She uses it, I've noticed, to fend off wellwishers on the campaign trail.

While slaving at her Ph.D., Susu managed to raise five children, rushing home between classes on her bike to nurse them. David, the oldest, got perfect scores on both parts of his S.S.A.T. and is a junior at Harvard; like his dad, he's in the Fly. Fiercely principled, Ethel has emerged from a period of green hair and nose rings and is now a pre-med at N.Y.U. Mary, a stunning young Grace Kelly look-alike, and little Quentin are at boarding school, and Frances is still at home—a large, rambling house in Cambridge.

The Weld children always had their heads buried in books, partly because Susu banned television from the house, partly because their parents were voracious readers. A typical evening chez Weld finds Bill and Susu in the living room—he immersed in Ford Madox Ford, his favorite novelist, she on the carpet, poring over an ancient Mandarin text.

The morning I met Susu at the house to interview her, she took me with a friend to the food bank, where we loaded cans and boxes donated by supermarkets into the Welds' green Suburban, battered by one of the kids' learning to drive. We delivered the food to Susu's Episcopal church and stacked it on shelves. This took several hours. I wondered whether there was a message in what we were doing—that private volunteer relief agencies can take care of the down-and-out as well as, if not better than, the government ones— but this just happened to be Susu's morning to get food.

I didn't realize until we spoke on the phone some time later that Susu is something of a closet Democrat. She voted for Dukakis in '88. "As someone who cares about girls impregnated by older men who float off into the sunset and leave them ruined and desperately poor," she has problems with her husband's proposal to deny welfare checks to unwed teenage mothers who cannot or will not identify the fathers. There should be an international effort to buy back the arms we have distributed to teenagers in Africa, she feels, in exchange for college scholarships. She has, she told the Globe, "serious doubts about the impact of the death penalty on minorities and lower economic classes," and is in favor of raising taxes for the wealthy back to 70 percent in the highest bracket.

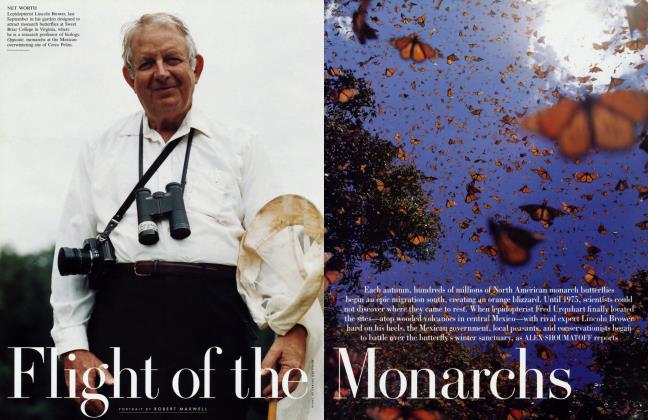

William Augustus White, Bill's greatgrandfather, was a founder of the Ausable Club in the Adirondacks, one of the last bastions of old Wasp privilege whose rituals are still intact. There in 1884 he built a rustic camp perched on a boulder and called it Taki-Tesi. The Welds have little to do with the summer social whirl when they come uptennis in whites, parties of golfers knocking balls around an exquisite, undulating nine-hole course, jacket-and-tie dinners. After a few days in Taki-Tesi they make for their fishing camp on a remote, practically inaccessible lake deep within the club's 7,000-acre property. They are rowed in a varnished Adirondack guide boat by a gruff, bearded fourth-generation guide named Brett Lawrence, whose great-grandfather sold some of the land to William White and his partners more than a hundred years ago. Once at the lake they are in Brett's hands. Brett is a Vietnam veteran, and he told me recently, "I'd be proud to take a bullet for that son of a bitch any time because he's going to do something for this country."

Continued on page 298

Continued from page 253

The lake is the scene of some very dedicated lake-trout fishing—the most arcane and sedentary form of trout fishing in existence. Hours, or even days, can go by without a nibble. You are rained on, eaten alive by blackflies, but the serenity, broken only by an occasional ululating loon, is unsurpassed.

One day Bill initiated me into the mysteries of the sport. After three or four hours all of a sudden my line slowly moved three inches away from the side of the boat. The important thing to do at this point, Bill explained, was nothing, except to carefully pay out line. A trout was chewing on the six-inch chub with a hook in its spine I had lowered 50 feet down, to within 6 feet of the lake bottom. The fish gradually took the line out about 15 feet, then stopped. Bill said to count slowly to five, then to set the hook hard, and suddenly I had Moby Dick—a 31incher that took half an hour to land, my bamboo fly rod bent in two. Bill was completely focused on my catching a fish, and the patience and skill with which he talked me through each crucial step revealed a generous side to him that I had never fully appreciated. As one of his inlaws puts it, Bill Weld is "moral."

Spending most of the 70s comfortably ensconced in the Boston firm of Hill & Barlow, Bill ran for state attorney general in 1978 and suffered one of the most crushing defeats in Massachusetts history, carrying only 2 of the state's 351 communities. The defeat didn't seem to bother him. During this campaign he introduced one of his mantras, which anticipated the current Republican platform by 10 years: there is no such thing as government money, only taxpayers' money. Other mantras would follow. "I want the government out of your pocketbook and out of your bedroom." "Crime, welfare, taxes."

Not all his ideas are so simplistic, though. At a breakfast for the New England Broadcasting Association, he was brimming with creative legislation: maybe college tuition should be made a federal tax deduction, he suggested. He was concerned about "pension portability," because "today the average person has four to six careers," and he felt that people who had been laid off should be allowed to dip into their I.R.A.'s and 401(k)'s without punishment. But on these points he wasn't much different from Kerry.

In 1981, President Reagan named Weld U.S. attorney for Massachusetts. Weld proceeded to lock up Boston Mafia bosses for lengthy terms, and placed then Boston mayor Kevin White on the hot seat for corruption in his administration. In 1986, Reagan brought him to Washington as assistant attorney general in charge of the Justice Department's Criminal Division. His boss, Edwin Meese, was involved with two figures who had become targets of a grand-jury investigation of Wedtech Corp., a military contractor. Meese himself became the subject of independent-counsel probes into both Wedtech and an aborted billion-dollar Iraqi oil pipeline project. "Our continued presence there was a silent testimonial that everything was fine, and we didn't think that it was," Weld told me. So after two years he did the honorable thing: he resigned. Perhaps to discredit Weld in case he ever testified against Meese, Weld says, an anonymous letter accusing him of having smoked marijuana at a friend's wedding in Virginia several years earlier had been sent to the Justice Department's inspector general. Weld was completely cleared of the allegation.

Weld was already thinking of taking on Kerry in 1990, but, according to Peter Brooks, Susu said to her husband, We have a great house, the children love their school—if you have to run for something, why not governor? So he ran against Boston University's John Silber and won with 51 percent of the vote.

Weld had promised to balance the state budget without raising taxes, but Dukakis had brought the state to the brink of insolvency and left Weld with a $2.5 billion deficit—"a fiscal Beirut," as Weld called it. He fell to the task like a management consultant hired to prune the deadwood from a floundering company, dismantling what Reader's Digest called "the nation's most entrenched welfare state, with 32 optional Medicaid benefits, from eyeglasses to Christian Science nursing. A mother could even get benefits for her unborn child in its first trimester." Typical of his good Karma was the windfall the state received when a clerk discovered in Weld's second year in office that Massachusetts had neglected to collect $400 million in federal Medicaid reimbursements; the regulations were so byzantine that this oversight hadn't been apparent before, and the state legislature voted the woman a $10,000 bonus.

The biggest flap was over a joke that backfired when Weld mailed to the media a snapshot of himself standing next to a wild boar he had just shot in a private hunting preserve in New Hampshire, with the caption "It was him or me—honest!" This rubbed animal-lovers, hunters, and anti-elitists alike the wrong way. But Weld has an engaging way of instantly and sheepishly admitting his mistakes. "It's easier to tell the truth," he explained once, "because then you don't have to remember what you said."

The Globe's assessment of his first six months was that his gubernatorial style was "notably short on angst, micromanagement, and midnight oil." The article quoted Democratic political consultant Michael Goldman as saying, "Nothing in his career has put him in the position of dealing with people who are not empowered by virtue of who they are. What he has is the comfort level of never having to be afraid."

Weld is in many ways a species of Republican that isn't in vogue at the moment, a throwback to an era when men unwound from their day at the office with a cocktail or two. Repealing Dukakis's ban on liquor in the statehouse, he instituted off-the-record "Board of Education" meetings once or twice a month, at which drinks were served to the press corps and people got pleasantly sloshed. There is footage of him slurring the word "Gingrich" at his last inauguration party. But Weld's drinking has actually been a political asset. "It was a major way he bonded with the urban Democrats and shattered the stuffed-shirt image and overcame their instinctive suspicion of guys like him, who had made their sainted grandmother scrub their floors on their hands and knees," Jon Keller, who aired the party live on Channel 56, told me.

At 1:45 on the morning of March 31, 1993, the police pulled over a weaving car. The driver turned out to be Ronald Kaufman, formerly George Bush's White House political director and now the Republican National Committee's strategist for Massachusetts. Kaufman failed to walk a straight line heel to toe and to balance on one foot, and he blew a .10 into a breath-analysis machine, an alcohol blood level at which a driver was considered legally drunk in Massachusetts at the time. He confessed that he was returning from a poker game at Governor Weld's. (Weld liked to play well-lubricated, highstakes poker games with his friends.) Practiced at saying no more than he had to, Weld admitted to the police that he had seen Kaufman with "one glass of an amber-colored liquid in front of him."

Since the incident the press has been merciless about Weld and his amber-colored liquid. The "Board of Education" meetings have, of course, stopped.

Weld's pro-choice and gay-rights stances do not endear him to the conservatives who control his party, but his presidential viability for 2000 could bloom if Dole loses and the three W's—Whitman, Weld, and Wilson—make a move to bring the G.O.P. back to the center. The only problem is that the star of his species is not Bill but Christie Whitman. If Bill is miffed that Christie has stolen his thunder, he hasn't let on. "Christie and I are joined at the hip," he told me.

Whitman is lavish with praise for Weld, who, she said, was "a wonderful role model. One of the reasons I got elected when I proposed to cut taxes and the budget and the world would not come crashing down was that I could point to what he did in Massachusetts. I think he has a big future."

Barney Frank, eighth-term Democratic congressman from Massachusetts, has his own take: "Weld has a set of characteristics that are either charming or quirky depending on who you talk to. I don't think he's presidential material, because people need a higher comfort level in the gravitas of their candidate; they don't vote for wise guys. Bill is one of the most secure individuals, which is why I was surprised by his debate performance, where he overdid showing that he is not lackadaisical. More of his ego appears to be tied up in this race than I would have thought, and this is a problem for him."

While Weld was a late bloomer who didn't run for office until his mid30s, John Kerry already seemed to be running for president at the cloistered, prestigious St. Paul's School, in the woods outside Concord, New Hampshire. The Kerrys were a politically active family. John's older sister had him out soliciting donations for Adlai Stevenson door-to-door on the streets of Georgetown when he was eight. One afternoon in 1960, he went into Boston to hear Senator John Kennedy campaign for the presidency. Kerry was hooked. It seemed almost prophetic to him that he possessed the same initials, and he took to signing his papers at school "J.F.K." "If Kennedy had been a Republican, John would have been Republican," his sixth-form roommate, Lewis Rutherfurd, now a Hong Kong-based venture capitalist, told me. Later, Kerry would date one of Jackie's half-sisters. "Kennedy touched my idealism with his Peace Corps, his vigor, and his huge, jingoistic, simplistic concepts that were as exciting as they were wrong," Kerry recalled as we were having lunch in the Senate restaurant. "Now, in many ways it is Bobby who is much more intellectually intriguing, who was tapping into currents that are very much alive."

Young John Kerry was multitalented-fluent in French, a three-letter man (soccer, hockey, lacrosse). But he did not possess natural charisma. Weld has it. Kerry has it now, but he had to work hard at it. Kerry was good-looking, smart, promising, and obviously ambitious, but there was something even then that rubbed people the wrong way. A St. Paul's classmate of mine recalled that "Kerry was frequently read and painted early as having an unctuous insincerity, as being cold and calculating and false at heart, as a prig, like a TV newscaster who can't turn off the on-camera delivery." Many of Kerry's peers don't like him. "The big problem with Kerry is himself," a Harvard classmate told me. "I met him at a Christmas party a few years ago, and he couldn't stop talking about himself. He wasn't listening to anything I was trying to say, and it was highly annoying. When I see him I go 'Yuck.' " One Globe columnist endorsed Kerry before the 1984 senatorial election with the tepid direction to "just hold your nose and vote."

As Kerry looked back on his youth, he once admitted to The Washington Post there was an "element of brashness." He grew up in Washington and in Europe, he explained to me, where his father was first an air-force pilot, then a diplomat. The family kept moving—Oslo, Paris, Berlin. By the time he hit St. Paul's after boarding school in Switzerland, he had been to seven schools; moreover, he was Catholic, so, unlike Weld, he found it hard fitting in with Episcopalian, East Coast preppies, and developed a cocky shell to disguise the fact that, as he told me, he was ill at ease.

Despite his name, there is nothing noticeably Irish about Kerry; it is Weld who has the blarney and the twinkle. By John's grandfather's generation, the Kerrys were living in Austria. On his mother's side John is a Forbes, not the Forbes of the magazine but of the clipper-ship dynasty that owns the majority of the Elizabeth Islands southwest of Woods Hole. Most summers John goes to Naushon, the largest of the Forbeses' private islands, where he sails and rides and windsurfs. According to a former aide of President Clinton's who visited him there a few years ago, "Kerry is beautiful on a horse." Sometimes he goes to a smaller island, Nashawena, which has a "ton of sheep," Bruce Droste, who is married to Kerry's cousin Diana, told me. The clan traditionally had a boisterous house party to gather the sheep in the spring, and another to separate the rams in the fall. "We enjoy the outdoors, and we're both go-getters," Droste went on. "There is a side that John guards, but he has extraordinary empathy. When the Rodney King verdict set off the riots in Los Angeles, he called and said, 'Let's go to church.' He took me to the Twelfth Baptist Church in Roxbury. We were the only whites except for one guy in the choir. The minister invited him to say a few words, and he extemporized a sermonette that captured the pain of the moment and had tears streaming down everyone's face."

From St. Paul's, Kerry went on to Yale, where as a freshman he debated and won office in the Political Union. He joined Fence, a social club for the St. Grottlesex crowd, much like the Fly, and was inducted into Skull and Bones, the famous secret society to which some 15 Yale seniors are admitted each year. (George Bush was one.)

When he graduated in 1966, the Vietnam War was going full blast, and, not sure what he wanted to do—maybe politics or journalism—he enlisted in the navy. He was of course aware that some Kennedy-esque combat citations would look good on his resume, and thoughtfully took along a movie camera; an ad containing footage of him walking on a dike would run in a senatorial campaign in 1990, and is running now. He requested transfer from a safe post behind the lines to—there being no PT boats—a swift boat patrolling the Mekong delta. February 28, 1969, found 25-year-old Lieutenant J.G. John Kerry at the helm of one of three "swifties," similar to the ones in Apocalypse Now, cruising the Bay Hap River, firing on huts and sampans suspected of harboring Vietcong. He beached his boat and led an attack into blazing enemy fire, mowing down with his M16 a man who had jumped up with a loaded rocket launcher—for which he was awarded a Silver Star. Two weeks later, he ran into an ambush, was wounded in the arm, and withdrew. But, discovering that one of his men had fallen overboard, he returned. "From an exposed position on the bow, his arm bleeding and in pain, with disregard for his personal safety, he pulled the man aboard," read the citation that accompanied his Bronze Star with combat "V" and the first of the three Purple Hearts he would eventually win.

War changed him. He lost close friends, and he still suffers from a recurring nightmare of being attacked by venomous snakes as he swims up the Mekong River. His kid brother, Cameron, a Boston lawyer who converted to Judaism, has said the war made John more willing "to take risks, to be on the outside, on the edge." Lew Rutherfurd said, "Vietnam solidified everything he wanted to do. He went into public service to have a voice so that sort of thing never happens again." Kerry had felt betrayed. "You come home and discover that people who are running the war are just interested in covering their ass," Jack Blum, a former aide, told The Boston Globe. "Meanwhile, real people are dying real deaths."

In April 1971, Kerry mobilized 5,500 vets to march on the Washington Mall to protest the war. Many were in wheelchairs, including Long Islander Ron Kovic, who would be immortalized by Tom Cruise in Oliver Stone's movie Born on the Fourth of July. Kerry supplied "the power and restrained dignity . . . [and accomplished] one of the most astonishing feats of public leadership I have ever witnessed," Globe columnist Thomas Oliphant wrote this spring on the protest's 25th anniversary. Appearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Kerry, dressed in fatigues and wearing his ribbons, gave a moving speech. "How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?" he asked. Senator Claiborne Pell expressed the hope that "before his life ends, [the witness Kerry] will be a colleague of ours in this body." A bill in Congress to lower the minimum age for senator to 27 was immediately dubbed the Kerry Amendment.

On the following day, April 23, a group of Vietnam Veterans Against the War including Kerry gathered on the Capitol steps and dramatically flung their medals over a six-foot fence. Twenty-five years later, I watched Kerry hold forth on the same steps to a field of Massachusetts six-graders and their parents. "I hope you appreciate the beauty you're paying for," he told them, "and I hope you leave here with a sense that the government is struggling with some very tough issues." He was a total pro. It was like watching Scottie Pippen shoot free throws. One kid asked whether children born to illegal aliens in the States automatically became U.S. citizens. "At the moment, yes, but I think we may have to do some rethinking about that," Kerry answered, then he turned to me and said, "Kids always ask the purer questions."

Some time after the war protest it came out that the medals Kerry had repudiated were not his own; he kept his and chucked someone else's. John Brock, who went to St. Paul's for two years, fought in Vietnam, and worked with Kerry on trying to get an accounting of the last missing-in-action soldiers, told me, "There was a lot of emotion over the medals, swinging one way or other, and he was a young guy caught in the hysteria of the moment. And I don't think there's a lot of mileage in what he did with his medals a long time ago. People don't care. We learned this from Clinton's [draft deferment]." It wasn't till 1984 that Kerry admitted the medals weren't his. "It's such a personal thing," he told The Washington Post. "They're my medals. I'll do what I want with them. . . . People say, 'You didn't throw your medals away.' Who said I had to? . . . It's my business. I did not want to throw my medals away." In the end, perhaps, Kerry was astute enough to realize that his most lasting political asset was having been a Vietnam veteran, not a Vietnam Veteran Against the War.

According to Tom Vallely, Kerry's longtime friend, who is now the director and Vietnam specialist of the Harvard Indochina-Burma Program, "John wanted to end the war, and he embraced running for Congress for that end." In 1972, after some highly publicized "district shopping," he ran for congressman from Lowell, claiming his parents' residence as his own. It was a bitter campaign in which a local newspaper owner, Clem Costello, attacked him viciously, challenging his patriotism, and despite appearances by George McGovern and Ted and Caroline Kennedy, Kerry lost.

He enrolled in Boston College Law School, then joined the Middlesex County district attorney's office. There he successfully prosecuted a major organizedcrime figure, instituted rape counseling, and whittled down the backlog of cases from 11,000 to about 250. In 1980 he ran for Congress again but pulled out in favor of Barney Frank. Finally, in 1982, he won his first elective office, as Michael Dukakis's lieutenant governor.

That year he separated from Julia Thorne, the daughter of a moneyed blueblood family, whom he had married in 1969. They had two children, Alexandra and Vanessa, who are now at Brown and Yale, respectively. "Julia's a fascinating woman, but she needs a lot of care and attention, and John just wasn't there," a close friend explained. The reason for this, according to Tom Vallely, was that John is also "high-maintenance. You don't get much attention yourself." "Julia was going her way, and John was going his," the friend continued. She is now living in Wyoming and writing.

In 1984, Senator Paul Tsongas was battling cancer and decided not to run for re-election, giving Kerry the chance to face off against millionaire high-tech entrepreneur Ray Shamie. The race was shaping up into a battle of ideologies until Shamie's past connections to the John Birch Society came to light. The South Boston Irish found Kerry too slick, pretty, and ambitious, and at the Eire Pub, where Weld would one day buy a round for the house, a Washington Post reporter was told "they don't think he's one of them. He's half WASP, you know." In spite of a TV ad that showed him standing in front of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, making it seem as if all 58,000 names were endorsing him, and angering vets who didn't agree with his anti-war politicking, Kerry won. He became one of the few freshmen to win a seat on the Foreign Relations Committee, where he had testified 14 years earlier. Senator Pell welcomed him. Most of Kerry's senatorial accomplishments have been in the area of foreign affairs.

In 1987, Kerry became the chair of a new subcommittee on terrorism, narcotics, and international operations. Well before the Iran-contra scandal hit the front pages, he was investigating Oliver North, and his subcommittee was looking into Manuel Noriega long before Noriega was indicted by the Justice Department. The year before, when Weld had joined Meese's Justice Department, Kerry was already going after Meese for shunting aside allegations of illegal transactions with the rebels in Nicaragua. "It's like having the fox guard the chicken coop," Kerry complained—a sentiment with which Weld by 1988 would have heartily agreed.

Kerry also uncovered money-laundering by the Luxembourg-based Bank of Credit and Commerce International; B.C.C.I.'s lawyer Clark Clifford, a Democratic icon for decades, had some explaining to do. Kerry became one of the most visible figures in the war on drugs in the late 80s, calling for such measures as withholding aid to international trafficking centers like Mexico, Panama, and the Bahamas. The focus of the war then was on producers. Kerry feels there should be more commitment on the demand side—drug education, treatment for the apprehended, etc. Weld agrees. "I'm not a supply-sider when it comes to the drug war," he told me. Neither candidate is in favor of legalization.

In 1990, Kerry was re-elected, defeating wealthy businessman Jim Rappaport despite a spot on TV that showed an unflattering portrait of Dukakis morphing into Kerry. The following year he became chairman of a special panel to investigate whether any P.O.W.'s or M.I.A.'s were still alive in Vietnam. By mid-1992 he had accounted for all but 80 or so of the 2,266 missing servicemen, and two years later he inspired bipartisan praise for pushing a bill to put 100,000 more policemen on the streets. "There wouldn't have been a Clinton crime bill without Kerry getting him to buy into the notion of putting up some serious money," Adam Wal insky, a former speechwriter for Bobby Kennedy, told me. "To this day it wouldn't have gotten anywhere if John hadn't been jumping up and down. In the Senate right now there isn't an enormous amount of energy. There are a lot of nice people with good intentions, but not many with drive. It's very rare that you see a guy like Kerry who sends his staff to talk to senators on other subcommittees."

In his two terms with the Senate, Kerry has cast more than 4,000 votes and quietly amassed a good deal of influence. I watched him in action for two days, struggled to keep up with him as he briskly strode from one meeting to the next down the endless Kafka-esque corridors of power in the belly of the Capitol and its annexes. "Weld would never find his way around here," he observed humorously.

The brash young Kerry has clearly grown into a statesman. Deeper, wiser, he has made peace with himself and come into his own. One can't help feeling that it would be very sad if this brilliant career were to come to an end, particularly with so many senior Democratic senators hitting the road.

We reached the spot where in 1988 Kerry successfully performed the Heimlich maneuver on Senator Chic Hecht, who was choking on a piece of food. Hecht was one of the Republican incumbents Kerry, as chairman of the Senate Democratic Campaign Committee, had targeted for defeat. "Now can I go back to being partisan?" Kerry had asked with a grin after Hecht thanked him profusely for saving his life. At one point Kerry and Ted Kennedy passed right in front of each other, but not a word or even a nod of recognition passed between them, which seemed odd because two hours earlier they had put on an impressive dog-and-pony show urging that the Boston Harbor Islands be turned into a national park. I wondered how close they are personally. Kennedy was reportedly miffed last winter when Kerry didn't choose the brother of Kennedy's wife, Vicki Reggie, as his media consultant for his re-election campaign. Kerry would be much better known if he had not spent his senatorial career in the shadow of one of the greatest legislative giants in history. But when I spoke with Kennedy a few weeks later, he had nothing but praise for his junior colleague: "John is one of the most fluent, eloquent voices that we have in the Democratic Party," he told me. "He's one of the leaders people really look forward to working with, because he knows how to get things done; he's a workhorse, not a show horse, and that has won him respect on both sides of the aisle. The president listens to him. When there's a bit of injustice, he responds in a natural, emotional, and visceral way. He has taken on some very tough issues. That whole work on the M.I.A.'s was a no-winner, yet it was something that burned on the conscience of the nation. Maybe it wasn't something that had a resonance in North Adams or Webster, but John helped put a piece of our history more behind us. We've worked very closely, and I have great affection for him. Teresa has been enormously warm and attentive at Sun Valley to my son Teddy junior [who lost a leg to cancer but is an avid skier]. You can always tell the character of a person through a child's eyes."

For 10 years Kerry was one of Washington's most eligible bachelors and went out with assorted starlets and socialites. Spotted with the likes of Morgan Fairchild and Catherine Oxenberg (each of whom he claims to have only dated briefly), bombing around in a Chrysler convertible, performing weekend aerobatics in a rented stunt plane, he was dubbed the Senate's Romeo. In 1992 at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro he was smitten by the vibrant and very rich Teresa Heinz. A pert brunette, Teresa was born in Mozambique, the daughter of a highly cultivated Portuguese oncologist. Teresa is soft-spoken and cozy, yet passionately concerned about the world's problems.

Her first husband was also a U.S. senator. John Heinz III was sweet, handsome, and a thorough gentleman, and he and Teresa were devoted to each other. "They had a happy marriage, which is rare in politics," Wren Wirth, wife of then senator Timothy Wirth and one of Teresa's closest friends, told me, "and now she's having another one." But in April 1991, Heinz's plane collided with a helicopter near Philadelphia International Airport. Teresa, of course, was devastated to lose the love of her life, after 25 years of marriage. She still refers to Jack as "my husband" and has kept his name. When I visited her in Washington, I saw photographs of him prominently displayed. "If Jack Heinz were alive today, Bill Clinton would not be president," she told me firmly. Teresa was left with three children, three-quarters of a billion dollars, and the responsibility for several Heinz foundations, through which she has given away some $170 million in grants. In foundation circles she is known as Saint Teresa. Her life has been like a mini-series, or the hugely successful Latin American primetime television soap opera of several years back, The Rich Cry Too. She has lost, besides Jack, four close family members in accidents, not to mention her country, a tropical paradise that self-destructed in a savage civil war. Her money, Wren Wirth told me, is small consolation for what she has been through. Like Susan Weld, Teresa has tremendous character and is completely down-to-earth; either one of them would make a great First Lady. "I am still the same person I always was," she told me as we had tea at her and Kerry's $2 million town house, which until recently was a convent on Boston's Louisburg Square.

I had dinner with Senator Kerry and Teresa at their brick mansion in Georgetown, which during the 19th century was the home of a Russian ambassador. Teresa and Jack Heinz had decorated it with an exquisite collection of German, Flemish, and Dutch old-master still fifes. She also has lavish residences in Pittsburgh, Nantucket, and Sun Valley. There is a grand piano in the Georgetown living room; in her youth Teresa had contemplated becoming a concert pianist, she says, but gave it up because her fingers "were too small."

She is still devoted to classical music; the acoustics of Heinz Hall, in Pittsburgh, whose renovation she was involved in, are now said to rank among the world's best. Teresa is a perfectionist; she has been known to be short-tempered with the help, but Wren Wirth told me that "she is no more demanding on anyone than herself." Her schedule is, if anything, even fuller than John's.

As their romance kindled, John took Teresa to—guess where—the Vietnam Memorial. They were married in May 1995 on Nantucket. "Teresa is just the right person for him," a friend says. "They both want the same thing—to do good and help the world. Teresa's just a great, fun girl, but she's very astute and driven in her own way. John has finally conquered his demons and is enjoying his success."

Contrary to popular perception, Kerry claims to have no interest in the presidency for now. He pointed out that he was one of the few members of his Senate class of 1984 who haven't run for president, and said he was completely fulfilled doing the nittygritty of a senator. Weld, he felt, has blown it because he should have been running for president already. At 11:30,

John excused himself from our dinner because he had a hundred pages to read before he went to bed. At a press breakfast at nine the next morning he was his usual eloquent, senatorial self. Kerry's energy is incredible. He wolfs down huge platefuls of food and has one of those rare, enviable metabolisms that bum it right off. His friend Bruce Droste ascribes his "mind-boggling, endless energy level" and "increased passion for life and people" to his Vietnam experience. "John is just go-go-go. He has a mind that is always there. When the gauze comes over your eyes, he snaps to and is absolutely there." Teresa explains that he "has the creed of the vets. Every day is extra."

The Boston press made much of an incident in which Teresa parked her Cherokee in front of a hydrant on Louisburg Square; this "spoke volumes," a Globe reporter told me, about how Teresa feels she is above the laws the rest of us live by. But the nuns had reportedly parked in front of the hydrant for years and the press had never gotten on their case. I

think this spoke more about the Fourth Estate's culture of resentment of anyone who is rich or beautiful or successful or looks as if they're having a good time. Teresa has been taking a beating in the local press. You can have that kind of money in Boston, but you can't spend it that way. Teresa defused some of the resentment by bringing a plastic hydrant to Billy Bulger's St. Patty's Day breakfast. "I was out finding a parking [space] and couldn't find one, so I made one," she told the crowd, which roared.

But I noticed one thing at dinner with the Kerrys. The Portuguese cook went around the table with a delicious pasta with morels, and before I could get to them, Kerry had fished out all the best morels for himself. This was in stark contrast to the Welds, who when they have you over to dinner do their own cooking and wait on you themselves, and when they come over to your place they insist on doing the dishes. Altruism is not something that seems to come naturally to Kerry. But this does not mean he is any less effective a warrior for the good in the Senate. In fact, politically he is more altruistic than Weld.

Weld did a lull Greg Lougams because the flu shots he received were rumored to have been about three fingers deep."

The outcome of the race, Rob Gray, Weld's flack, told me, will depend on the debates and the TV ads; 70 percent will be issues, and the rest will boil down to character and ethics. Weld, presumably concerned that he could be blown out of the water by Teresa's "fabulous ketchup fortune," got Kerry to agree to a campaign-spending cap of $6.9 million apiece—believed to be the first such voluntary agreement of its kind between senatorial candidates in modern American political history. But there is still no agreement on negative campaigning, which Kerry has defined as: If we're goingto trash each other on television, let's do it ourselves and not get some third party to do it. That means the campaign could get down-and-dirty in the months to come. Kerry's personal resources are limited; his income taxes for 1995 were $34,891 on a salary of $126,179. Teresa filed separately and has refused to release her taxes, or to say whether she and John have a pre-nuptial agreement.

But he told me last spring, "Neither Teresa nor I believe in the notion of spending huge amounts of personal money to buy elections. But we reserve the right to borrow not to be outspent and to defend our family, including me." Teresa told me she believed that Weld had had her investigated (which he flatly denies), and said, "If I have to defend my name and my husband's, I will spend $50 million if necessary."

The hitherto high tone of the race is already beginning to degenerate. The Kerry people could make hay with Weld for going to a Pete Wilson fund-raiser instead of consoling the victims of a tornado in western Massachusetts in May 1995, and for being nearly beside himself over the death of Jerry Garcia and wanting to fly the flag on the statehouse at half-mast. The Weld people could focus on Kerry's votes to increase taxes and against balancing the budget, or on minor irregularities with some of his campaign contributions and bank loans.

Kerry had opened a sizable, 13-point lead by last spring, according to one poll. A column in May by the Globe's Scot Lehigh about how "Weld's pursuit of Kerry seems to be losing traction" pointed out that it is usually the incumbent's record that is under scrutiny, but in this race it seems to be Weld's. It looked as though the governor was forsaking the commonwealth for campaigning. The Boston Globe noted that Mitchell Adams's revenue department failed to cash $146 million in tax checks, costing the state $20,000 a day in lost interest, and that 700 sex offenders had been let out early through work-release programs and paroled. And where were all the new prisons Weld promised to build? The Department of Social Services had let convicted criminals, including child abusers, kidnappers, wife beaters, and drug dealers, become foster parents, and the governor did not display impressive leadership qualities when he allowed anti-abortion activists nearly to hijack the state's delegation to the Republican convention.

To make matters worse, on May 18 the governor turned ghastly pale and fainted as he was stepping up to receive an honorary degree from Bentley College, outside Boston. His doctors said that it was flu. "You can all gather close so I can breathe on you," he told the press as he left the hospital. But some media jackals were merciless. The Globe's Mike Barnicle said Weld did "a full Greg Louganis" because the flu shots he received were rumored to have been "about three fingers deep" and to have "been administered by a Dr. J. Daniels of Tennessee."

Weld seemed fully recovered when I saw him up at the Ausable Club over Memorial Day. He had just caught the biggest lake trout that had ever come out of the lake: 15 pounds, 35 inches. The press made fun of this too ("What was the water, amber-colored?" asked the Herald's Joe Sciacca), but I knew the importance of that catch: Weld had gone to the lake in his hour of need, and it had given him a clear sign, a wonderful re-empowerment, like Arthur getting the sword from the Lady of the Lake. Weld came back from a 25-point deficit in his 1990 primary. It is an old saw that the only poll that matters is the one taken on Election Day. The latest poll has Weld just a little ahead and gaining momentum. He had hoped to endear himself to Massachusetts liberals with a strong and courageous pro-choice stand at the Republican convention, but was silenced by organizers of the event, who accused him of trying to boost his standing at home at the expense of party unity. Kerry loves being senator but seems a bit bored with campaigning, and during some of the debates he has looked a little worn. Weld, on the other hand, seems bored with governing but has plunged into campaigning with zest. Each is hoping that the other will make some terrible gaffe or that something terrible will be dredged up from the other's past—but my guess is neither will happen.

Meanwhile, Susan Gallagher, a 37year-old mother of four, has jumped into the race as the candidate of the newly formed Massachusetts conservative party. She could siphon off up to 4 percent of Weld's votes, which might prove fatal in a close race. But neither Kerry nor Weld has in fact captured his party's traditional constituency. By midsummer the campaign still had "a topsyturvy, unsettled feel," The Wall Street Journal reported.

When I was in Washington, I rode up in the elevator of the Watergate with Howard Baker. "I know them both, and they're both fine men," he told me when I asked his opinion. My sentiments exactly. It's a shame for American politics that one of them has to lose. But, as a number of people have pointed out, if you like them both, a vote for Kerry will keep both of them in office.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now