Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

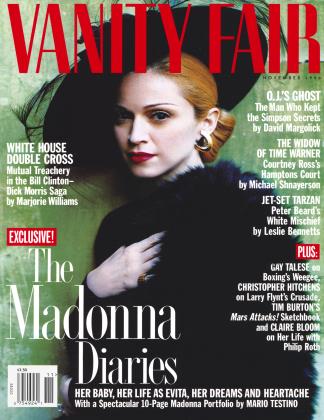

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFor an acclaimed actress, falling in love with novelist Philip Roth was first a joy and then a torment; after she made the bitter choice between him and her daughter, she writes, he disintegrated psychologically, making her the target of a vicious, irrational rage

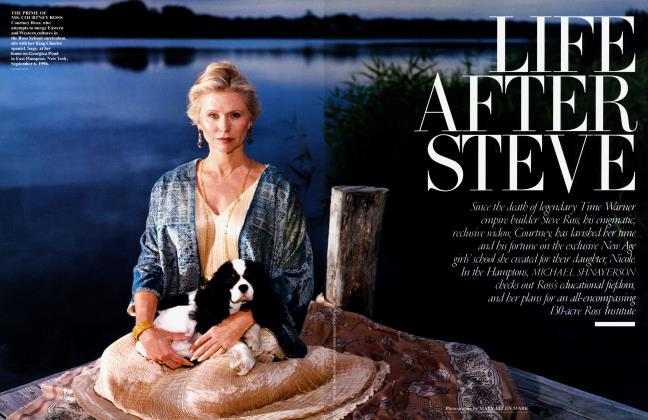

November 1996 Claire BloomFor an acclaimed actress, falling in love with novelist Philip Roth was first a joy and then a torment; after she made the bitter choice between him and her daughter, she writes, he disintegrated psychologically, making her the target of a vicious, irrational rage

November 1996 Claire BloomOur meeting was typical us and ridiculously simple. I was walking up Madison Avenue in New York City to have tea with my yoga, teacher; Philip Roth was walking down on his way to a session with his psychoanalyst. Philip was looking very professorial behind his glasses, and bent over to kiss me on the cheek. I told him I was on my way to Hawaii to make the Hemingway film Islands in the Stream, with George C. Scott, who I predicted would be a monster, like most of the testosterone-driven leading men I had recently had the pleasure of coming across. (He turned out to be a complete professional.) Philip silently pondered this for a moment, then said, quietly but firmly, "Not all men are."

Excerpted from Leaving a Doll's House, by Claire Bloom, to be published this month by Little, Brown & Company; © 1996 by the author.

We had first met in East Hampton, Long Island, in 1966. My husband, Rod Steiger, the actor, and I had taken a house for the summer months, and we had a good time there with our daughter, Anna, bicycle riding, swimming, performing a host of healthy summer activities. Neighbors invited us over for a drink; one of their houseguests was Philip. Roth was already a highly acclaimed young writer—the author of Goodbye, Columbus, a fine volume of short stories. I recognized his tense, intellectually alert face immediately from photographs. Tanned, tall, and lean, he was unusually handsome; he also seemed to be well aware of his startling effect on women. I was immediately attracted to him and he would tell me years later that he had also felt the same toward me. We were both attached—Philip to a beautiful young socialite, Anne Mudge, I to Rod—but neither of us forgot that meeting.

A few days after our Madison Avenue encounter, I went to Philip's apartment for coffee; we sat checking each other out. I had dressed as attractively as possible, and was determined to be at my most charming and witty. Philip was very seriously considering me from behind his glasses, sizing me up in a manner particular to him, taking every detail in, with intense concentration on each intellectual, psychological, and sexual aspect of the woman in front of him. To have such a mind as Philip Roth's fixed on your every word and gesture is both daunting and extremely flattering; but it was difficult to read his intentions from the emotionally neutral and sober expression that followed every comment I made. Though he had it to an immense degree when the mood took him, his brand of seductiveness wasn't charm; it was intelligence, the sort that passes as acute sensitivity by dint of an astonishing facility for understanding. He made no effort to conceal the caustic and judgmental sides of his character; as a result, I felt that I would never be able to measure up to the high standards he demanded both of himself and of his friends—and especially of the women with whom he became involved. But, confoundingly, he also appeared capable of great kindness and depth of feeling.

I gave Philip my address and took his. We agreed to write. I had to leave for Hawaii the following day.

We exchanged several letters, and when I arrived back in New York on February 16, 1976, there were flowers at the hotel to greet my arrival. "Welcome, Philip." Very careful and correct.

A week after, we admitted we were in love with each other. Philip spoke first, and his voice was suffused with pain and a kind of suffering; it was as though it hurt him to declare his love for me. I stayed in his apartment that night and for the nights afterward. By now I had only 10 days left of my stay in New York.

To my surprise, I overheard Philip talking on the telephone; from his end of the conversation I gathered that it was with a close male friend; they arranged to leave together in a few days' time for a vacation in the Caribbean.

This arrangement was a great surprise to me after the eager tone of his letters and affection he had shown since my arrival. I had expected to spend the time I had left in New York with him. This was my first glimpse of Philip's rigidity: he had arranged to go, and he was going. I suspected at the time that this trip might have been worked out before my arrival, perhaps as a safety valve to avoid becoming too emotionally involved; I thought it was even possible he now regretted it. But whether he did or not, he was going through with his original plan.

Soon after, I arrived back in London, where Harold Pinter invited me to appear on Broadway, under his direction, in a stage adaptation of Henry James's great novella The Turn of the Screw; the title of the play was The Innocents. The chance to return soon to New York and be once again with Philip seemed to be nothing less than providential. I had always admired Pinter, both as playwright and director, and been fascinated, since my teenage years, by the James story of psychological terror and erotic possession.

He knew I would make any compromise to support our relationship. If I was willing to jettison my own daughter... what could I ever deny him?

But there was even more to delight me. The rehearsal period was to be held in London, and Philip suggested that he join me there, and then we could return together to New York.

Although it was a joy to have Philip so unexpectedly with me in London, some of the problems we would subsequently have to face must have been almost immediately apparent to us both.

My daughter, Anna, was now a young woman of 16. Emotionally fragile as a result of my second marriage, to the theatrical producer Hillard Elkins, she was deeply distrustful of the strange new man in my life and full of anxiety. Those four weeks in London were both tense and happy. Philip and Anna viewed each other with civilized caginess and without much instant rapport. Knowing Philip better now, I can look back and honestly say that during this early attempt at family life he tried to treat Anna with understanding.

Philip and I returned to New York at the close of rehearsals for the opening of the play; Anna and my mother were to follow. I rented an apartment on New York's Upper East Side. Anna and my mother would live there; I ostensibly would live with them; it was, however, understood that I would spend my Sundays, when I would be free from performances, with Philip in Connecticut. Just how I would carry out this juggling act without a hitch, I wasn't entirely sure; somehow I hoped I could please everyone.

The Innocents, so well received in Boston and Philadelphia, opened to lukewarm reviews in New York. This near-perfect production, which would undoubtedly have run in London for 10 months, closed on Broadway after a run of only 10 days.

I had allowed myself to be lulled into a false sense of security, and security has no place in the life of an actress. I had expected the play to succeed, and made my plans accordingly: I'd let my house in London and rented an expensive apartment in New York. My mother thought it best to return with Anna to London, where my daughter could live with her for the moment; she suggested I try to sort my life out with Philip and join them later.

The chasm that was to come between my family obligations and my desire to be with the man I loved was beginning to show itself.

The evening preceding their departure was wretched beyond words. Anna, furious and justifiably hurt, said that I had once again chosen a man over her, which made me feel compromised and guilty; I feared Anna was right—perhaps I was unconsciously sacrificing her in favor of Philip. I wanted desperately to keep what I knew could be the first complete relationship of my life; I understood that my true chance of happiness was with Philip, and that I couldn't give him up.

To my great relief, a few months after we had begun our life together, Philip suggested that we try spending six months of the year in London, and the other six in the United States. I knew what a difficult decision this must have been for a man of Philip's temperament, that for a writer to change the place where he creates his work takes enormous courage. Philip was chained to his writing habits; he had never neglected to sit down at his typewriter, even in the first days of our relationship. I was deeply appreciative of this gesture. There was, however, one provision: he made it clear that he had no intention of living together in the same house as my daughter.

This mixture of kindness and cruelty, this coupling of generosity and selfishness, made me frantic with confusion. I told Philip that what he demanded of me was an impossibility; there was plenty of room in my London house for the three of us to live quite comfortably together. Eventually Philip agreed to see if some form of family life would be possible for him.

We moved to London and at first all was peaceful. Philip found a studio to work in; Anna had her own space upstairs, and we occupied the lower half of the house. I have no doubt whatsoever that this new existence must have been strange for Philip, who was used to living alone; now he was forced to share his life with a mother and daughter whom he viewed as too needily interdependent.

His lower jaw thrust forward, his mouth contorted, his dark eyes narrowed. This expression of out-and-out hatred went far beyond anything I could possibly have done to provoke it.

One evening, while we were living in London, I returned home after the theater to find Philip in a paroxysm of silent anger.

Anna and a college friend were in Anna's room on the top floor of the house, laughing and talking. He protested that their noisiness interfered with his concentration. I asked him why he hadn't gone upstairs to complain; he replied that it was my job. I obediently walked into Anna's room and asked them to be quiet; the girls apologized and complied. When I came downstairs, Philip refused to talk to me.

In the morning, after a strained breakfast, just as he was about to leave for his studio, he thrust a letter into my hand.

This missive, one of many I was to receive during the course of our years together, contained the following conditions: he wanted to continue his relationship with me, but under no circumstances would he again live in the same house with both me and my daughter; unless Anna agreed to move elsewhere, he would return to New York; we would spend the agreed six months of the year in Connecticut, but in London I would be alone.

He closed by repeating his intention not to end our relationship.

Although Philip's dislike of my daughter was transparent, as was his fierce competitiveness for my affections, I hadn't recognized how deep his prejudice ran where she was concerned. I was caught in the middle, with emotions and responsibilities tugging away on both sides; it was a no-win situation. Placing Philip's needs over Anna's meant hanging on to an important relationship at the price of my daughter's trust in her mother's protection; putting Anna's first meant keeping faith but surrendering a bond I felt with all my heart I couldn't live without.

It was a choice between the security of a companion and the welfare of a daughter. Anna was asked to move out. She was 18.

The circumstances were terrible: Anna witnessed someone she viewed as an outsider calling the shots in her own home and her mother unable to set any boundaries; understandably, she felt angry and betrayed. In addition, Henry Wood House, the student hostel to which she would move, was located across the Thames in one of the least salubrious neighborhoods of London.

But Philip had his way, and it has taken me a long time to accept the repercussions of his calculated move barely two years into our relationship. It wasn't about hatred for my daughter, though animosity may have been the catalyst—it was about control. Philip made character assessments the way surgeons make incisions. He knew I would make any compromise to support our relationship. If I was willing to jettison my own daughter in this manner, what could I ever deny him? I know I was diminishing my own character with each successive act of capitulation. These confrontations left me debilitated and unsure, and were to shape many of my future decisions.

He also understood that part of me that was afraid of him.

I had once seen a facet of his character that shocked me deeply. Angry over something I frankly no longer remember, he turned toward me with the face of an uncontrollable and malevolent child in a temper tantrum; his lower jaw thrust forward, his mouth contorted, his dark eyes narrowed. This expression of out-and-out hatred went far beyond anything I could possibly have done to provoke it. I remember thinking, with total clarity, Who is that?

That feral, unflinching, hostile, accusative, but strangely childlike face would appear increasingly in our years together, sometimes without warning, frequently without provocation, always out of proportion to the events that had given rise to it.

The power Philip held over me wouldn't have existed without his ability also to be a tender, thoughtful, and understanding man. Just as I feared the appearance of this "other" Philip Roth to such a degree that, in order to avoid him, there was almost nothing I wouldn't have done to make him disappear, I also feared to lose the Philip who was my dearly loved companion.

When Philip and I were alone in Connecticut, our time together was often sweet and gentle. There were good and there were bad times, as in every relationship. When he left the house in the morning for his studio, I would occasionally feel lonely and isolated in the depths of the country, but I found ways to make life more interesting. There were projects to work on, walks to be taken, meals to be discussed and prepared, and yoga lessons to be learned and practiced.

Late in the afternoon, Philip would leave his studio, take a long walk, and come into the house to light a log fire.

Reading books, exchanging books, discussing books: this was an essential method of communication between us in all the years we were together. My reading was mainly for my own pleasure, for historical research, or as a distraction from everyday life. But for Philip it was his most vital and consequential activity.

The widely held view was that Philip's gifts shone most brightly in the realm of the savagely amusing, but his work also contained a tenderness that wasn't often remarked upon. The first book he dedicated to me, The Professor of Desire, in which he described life in the country with a former companion, was far more lyrical than many of his later works. The Ghost Writer, the first of three novels tracing the life of Philip's alter ego, Nathan Zuckerman, was also set in a fictionalized version of the Connecticut house, and was a beautiful chronicle of the reclusive life of an author.

When I came to prepare, a few years later, dramatic readings of Charlotte Bronte, Henry James, and Virginia Woolf, our immersion in works by those authors came to life in a remarkable way. With Philip's advice, I prepared each performance with great care, and he proved to be a brilliant interpreter of character for theatrical presentation. To this day, I approach reading in the same scrupulous manner to which he spurred me.

In 1987, Philip began to suffer from insomnia, lack of appetite, difficulty in concentrating on his work—even to a layman, textbook symptoms of anxiety and depression. He became more and more exhausted and, in the end, completely collapsed.

He went to his psychoanalyst, who prescribed two drugs, Halcion and Xanax. Initially, Philip felt some relief, and was able to sleep without the dreams that had recently haunted him for long hours. At this point he began a harrowing, regressive slide back into his early childhood. Philip's mother had died in August 1981, and now, suddenly, he became her little boy again. He clung to me in a way he never had before, his entire body trembling with the desperate need for maternal comfort and reassurance. It was a beautiful summer, and the house was filled with brilliant sunlight. "Why don't we walk in the fields?" I asked. "Why don't we go for a swim?" He had become terrified of the water, and made slapping movements with the back of his hands like a child's first awkward paddle. "No, don't make me stay in the pool," he cried. There was nothing I could do to help. Philip disintegrated before my eyes into a disoriented, terrified infant.

To my knowledge Philip had never experienced a depression of such intensity. Had the doctors diagnosed his condition during this first episode and treated him with the appropriate medication, I believe he might have been able to control this devastating illness.

Then I reached the depictions [in Roth's novel Deception] of all the girls who come over to have sex with him-in the most convoluted positions, preferably on the floor.

We had little help and no advice; alone in Connecticut, we spent the better part of three months hoping against hope that his despondency would somehow come to an end by itself. From my point of view, Philip's mental coming apart is almost impossible to describe; but from his, there is a grueling and sobering account in his 1993 novel, Operation Shylock, which is neither inaccurate nor overblown. It was just as he recorded it, with the added factor, unmentioned in the book, that I was dangerously close to going down with him.

My strength—no, my endurance— was fading fast. Philip suggested asking his old friend Bernard Avishai, a fellow writer, to come from Boston and stay with us for the next few weeks, and I agreed.

I am convinced that Bernie saved Philip's life.

Less than a year before this episode, Bernie had suffered a similar breakdown. He also had been prescribed Halcion, and become suicidally depressed. Philip, who had feared he was losing his mind, was relieved to hear that his terrible situation could possibly have been drug-induced. For, in that case, he could see some end to the labyrinth in which he had become lost. Bernie put him in touch with his own doctor in Boston, who agreed with the hypothesis. With the encouragement of our longtime friend and doctor, C. H. Huvelle, Philip agreed with Bernie that the only way out of the inferno he was experiencing was to go "cold turkey" that very night. Bernie offered to stay with Philip during the next 72 hours, which he warned would be agonizing for Philip to endure—and, he stressed, for me to witness.

My first reaction was distrust: I didn't know Bernie well at the time, and was extremely protective of Philip. But the situation was desperate. I moved out of the bedroom and let Bernie take over his care.

Philip spent the next three nights alone with Bernie; in the morning they both emerged from their sleepless ordeal drained and shaken. I don't know what Philip experienced during those nights; he never spoke of it. By the time Bernie left us a week later, Philip, although still weak and frightened of a relapse, was already on the path to recovery. We spent some time on Martha's Vineyard with William Styron and his wife, Rose. For Philip to be with such an old friend helped him restore his spirits.

Sometime thereafter, he began sporadically to write again. He started on a new book; it was to be called Deception. Although his custom had always been, when he was enthusiastic about his work, to discuss it openly, this time the book was barely mentioned. I had no idea what he was writing about, nor any suspicion that he might have a reason to be less than informative about the contents of the new book.

I rarely visited his studio, which was only blocks from our apartment in New York City. I always respected it as his private territory. On one occasion I received unexpected good news in the mail and ran excitedly, letter in hand, to visit him. His reaction was cold, alarmed, and unwelcoming. I told him I would never interrupt him there again, and left.

When he completed Deception, he didn't invite me to read the material, as he had previously done with other books at this stage. The manuscript sat on his desk for three weeks; then, early one morning, he brought it to me before he left for the studio.

I eagerly opened the folder. Almost immediately I came upon a passage about the self-hating, Anglo-Jewish family with whom he lives in England. Oh well, I thought, he doesn't like my family. There was the description of his working studio in London, letter-perfect and precise. Then I reached the depictions of all the girls who come over to have sex with him—in the most convoluted positions, preferably on the floor. As Philip always insisted that the critics were unable to distinguish his self-invention from his true self, I mindfully accepted these Eastern European seductresses as part of his "performance" as a writer; but I was not so certain. Finally, I arrived at the chapter about his remarkably uninteresting, middle-aged wife, who, as described, is nothing better than an ever spouting fountain of tears constantly bemoaning the fact that his other women are so young. She is an actress by profession, and—as if hazarding a guess would spoil the surprise lying in store—her name is Claire.

I no longer gave a damn whether these girlfriends were erotic fantasies. What left me speechless—though not for long—was that he would paint a picture of me as a jealous wife who is betrayed over and over again. I found the portrait nasty and insulting, and his use of my name completely unacceptable.

Far earlier than usual, Philip returned home, carrying in his pocket an exquisite gold snake ring with an emerald head from Bulgari on Fifth Avenue. I was waiting for him, shaking with rage. I told him he had used me most shabbily. I told him I wanted my name out of the book. I told him that was the end of that; there would be no discussion. He tried to explain that he had called his protagonist Philip, therefore to name the wife Claire would add to the richness of the texture. I replied I didn't care whether it did or not. I reminded him that, like him, I was a public figure and would seek any means at my disposal—even legal means—to have my name removed. For once confronted by my opposition, Philip agreed to remove it from the novel. Then I accepted his guilt offering. I wear it to this day.

I found the portrait nasty and insulting and his use of my name completely unacceptable.... I was shaking with rage.

In early January 1990, I asked him to marry me. After 15 years together, after all we had been through in the course of our relationship, I thought that it was time he made me his wife, that marriage would be of immense significance to me. I made it clear to him that, whatever he decided, I would remain with him. He said he needed some time to consider the idea. From any other man this would have been an outright rejection; but after living with Philip, I knew him well enough to understand that he never made a commitment of any kind without giving every aspect a profound consideration.

I left for London to appear at the Almeida Theatre in a revival of Ibsen's rarely performed play When We Dead Awaken. Three weeks later, I received a typewritten letter that read: "Dearest Actress, I love you. Will you marry me?" It was signed, "An Admirer." It was typical of Philip to answer in this fashion: a humorous—and, in this instance, charming-twist on the most serious decision a man and woman can make together; a nameless, impersonal reply to that most personal of requests. Although the time in Connecticut was three A.M., I telephoned to say, "Yes. Yes. I will."

That early morning will remain with me always as one of absolute and radiant happiness.

We were married on April 19, 1990, in the apartment of our longtime friend Barbara Epstein, an editor of The New York Review of Books. Barbara and I filled the apartment with white flowers. Bemie made a beautiful toast hailing the union of "best friends," which was silently followed by the raising of glasses and sipping of champagne. Philip added a wry addendum of his own, in which he noted that our assembled friends, having waited expectantly so many years for this day, could finally get some sleep; it was received with cheers and applause. It was a wonderful beginning to our married life.

But something ominous had taken place during the interval between the time of my proposal and Philip's reply which I had chosen to disregard. Had I done otherwise, it would have given me the clearest message that the marriage was no more than Philip paying lip service to my desire to be married.

He had consulted his lawyer Helene Kaplan, and with her counsel a prenuptial agreement was drawn up, a document glaring in its absence of any provision for me should Philip decide, for any reason whatsoever, to seek a divorce. Under its conditions, he could terminate our marriage at will, with no further responsibility toward his wife; the apartment, possessions, everything reverted to him. I signed these papers two days prior to our wedding. So committed was I at this point to becoming Philip's wife, I accepted the insult offered, and chose to ignore it. I know that, had I objected, there would have been no marriage. We had been together 15 years, surely time enough for him to be certain I was scarcely out to get his money. I wanted to be his wife more than I had ever wanted anything: enough to turn my face away from this blow to my pride and my integrity.

After so many years of living together, I was Philip's wife at last. Often he would remark that, even to his own surprise, our marriage was giving him the greatest happiness; his only regret, he said, was that we hadn't married earlier, when we might have had a child.

All the strain that had grown between us seemed to vanish. The solitary months we began to enjoy again in Connecticut were balanced by the invigorating time we spent in New York. It was not to last long, however.

By the end of the second year, Philip's confidence in our relationship seemed to falter; he began to withdraw from me emotionally. Perhaps too much domestic harmony had become an obstacle to his creativity. Something unspoken was causing a rift, which came soon after in the form of another unexpected and totally unwarranted attack on my daughter.

Anna had been to visit us in Connecticut twice since our marriage—only for a few days at a time. I was happy to have her, and was under the impression that Philip and Anna had reached a kind of truce.

Without warning that something in her last visit had upset him, Philip handed me another letter—there had been a gap of many years since the last of these written injunctions—this time demanding that Anna was to limit her visits to Connecticut to only one week per year. He also made it clear that when Anna and I visited New York together, he would prefer that she not stay in our apartment.

I decided the only way to deal with his petty belligerence was to humor him and take no notice. I kept my relationship with Anna secret from Philip, and kept the contents of Philip's letter secret from Anna

In the winter of 1992, Philip completed Operation Shylock. He was more optimistic about this book than about any of his previous works. He talked about it incessantly, reading passages to me that were dazzlingly incisive and entertaining. I was sure he would once again confound his critics with his superimposition of one identity upon another upon another, while delighting his admirers, who, under the spell of his masterful game, understood and appreciated his multicolored weave of fantasy and fact. The sections recounting his Halcion-induced breakdown, recording the trial of John Demjanjuk in Israel, and a scene devising a meeting between a "real" Philip Roth and a "fake" Philip Roth were some of the best things he had ever achieved, navigating the difficult course between investigation and invention with a kind of genius. His publishers, Simon & Schuster, his friends, and his agent, Andrew Wylie, agreed that the book was, without a doubt, his masterpiece.

As with the first book that came at. the beginning of our relationship, The Professor of Desire, he dedicated Operation Shylock to me.

On the occasion of Philip's 60th birthday he was feted and honored both in New York and in his hometown of Newark for his achievements as an American writer; a documentary was also completed for British television. He was invited to go on tour, giving readings from his last book, Patrimony. Though he had developed a deep-seated fear of public readings and asked me to come with him to give him confidence, his performances were outstanding and often even inspired. It was one of the few occasions in our life that we traveled together.

During that month, I accompanied him to San Francisco, when an unexpectedly early review of Operation Shylock appeared in Time magazine. I read it first; it called the book superb. I ran back to our hotel and showed the article to Philip. As further notices appeared, however, it gradually became obvious he wasn't going to have the critical triumph he had confidently expected.

It appeared that this great novel was not to be a favorite with the critics. Although both Alfred Kazin in The New York Observer and Harold Bloom in The New York Review of Books praised it generously, John Updike's grudging estimation in The New Yorker came as a great blow to Philip's morale.

In bookstores, sales, which had started promisingly, began to fizzle out. Time suddenly withdrew its offer of a cover story.

Despite the intensity of his disappointment, Philip remained externally selfpossessed. We returned to Connecticut and tried to come to terms with our unmet expectations. The crest of the emotional wave he had been riding before the publication of the book transmuted into its polar opposite.

Philip began to suffer from a recurrence of his previous severe depression. By the summer it had become obvious that he was extremely ill, and quickly plunging headlong into the dark territory he had inhabited five years earlier—a bleak terrain with ramifications he and I both feared, though my fears were rooted in concerns for my own welfare as well as his.

When the trajectory of Philip's emotional swings became so extreme that I was unable to follow them in a rational manner, I began writing a journal. He became increasingly withdrawn and angry at me. In early August, Philip signed himself into Silver Hill Hospital in New Canaan, Connecticut. Here are a few pages from my account of the events that followed.

Monday, August 9 New York Apartment

I will never be able to forget what happened yesterday. In some very fundamental way I shall always be scarred by what was said in that room at the hospital.

Philip came into the room. When I tried to put my arms around him, he turned to stone. We sat down with the doctor between us, like adversaries. He looked pale and drawn. I asked why he was trembling.

Philip stared at me with complete hatred, his jaw thrust forward, and snarled, "Because I am so angry with you."

"Why are you so angry with me?" I tried to be calm.

Philip went on to tell me, hardly pausing for breath for two hours. ... He spewed out every mistake I had ever made. Everything that had made him angry over our 17 years together. Nothing was omitted. Some were ridiculous; some were petty; some, unfortunately, were true.

"Philip, you're demonizing me. You're turning me into Maggie [Margaret Martinson, Philip Roth's deceased first wife]." He disregarded this.

I told him I had taken good care of him through his knee operation, heart operation, and been at his side through two major breakdowns. Philip looked at me coldly; he replied, "I am sorry to disillusion you on that point. You were no help to me whatever."

Although the expression on his face was poisonous and hateful, his voice never rose beyond its usual level.

Tuesday, August 10

These three days have been the most brutal of my life. In these sessions I've remained mostly silent. I am paralyzed in the face of this hatred. I also believe that Philip is seriously ill. Finally, I asked him the reason why, if he has hated me for so long, he married me three years ago. His snarled reply—"Who knows"— said it all.

Thursday, August 19

Dr. Bloch [not his real name] telephoned from Silver Hill to say Philip has asked if I'll let him have the apartment for six months. Apparently he can't face living alone in the country. Now he wants to be in the city, near his friends, near his psychotherapist, and will give me $5,000 a month to cover my expenses and accommodations in a hotel or furnished apartment. Translation: I must find somewhere else to live while he recovers alone. I asked for time to consider.

The request for me to move out made Anna suspect that Philip wants a divorce, and she told me to call a lawyer. He's trying to get me out of the apartment by making me feel guilty, she said. Maybe she's right.

On November 1 I received a strange message from the hotel operator. Someone called "Frederick" wanted to speak to me. Would I accept the call? I didn't know who "Frederick" was. When I accepted, I heard the receiver quickly replaced. I told Rachael, a good friend of Anna's—Anna was asleep in the next room—that I didn't like this: it was either a reporter angling for a story or someone delivering legal papers. The phone rang yet again; this time it was the front desk. A man was waiting downstairs, the concierge said, with a message he could deliver only in person.

He left me for Erda: a beautiful woman who had been a close friend to both of us.... As the saying goes, the wife is the last to know.

I was paralyzed. Rachael said we might as well get it over with; I allowed him to come up. He rang the bell, and handed me a folder from a satchel. Then, unbelievably, he asked me for my autograph, which I declined.

I opened the folder and found divorce papers, summoning me to appear in court within 20 days, and accusing me of "the cruel and inhuman treatment" of my husband, Philip Roth.

My own position was precarious. Assuming I had been disposed to bring a case against Philip in Connecticut to overturn the prenuptial agreement, one of the few alternatives available to me, it would have been a colossal gamble. Philip, who had more funds at his disposal and was hardly profligate in his financial affairs, warned me he would sooner lose $200,000 in legal fees than be forced to hand over a penny to me. My resources were inadequate; but, more to the point, I lacked the courage to take him on.

After a relatively brief period of negotiation and much against my lawyer's strong advice, I settled with Philip for the sum of $100,000. This sum could not buy even a one-bedroom apartment in New York. But it came down to this: anything was preferable to continuing a war of nerves between us; better to get the whole ugly business over with. My lawyer's parting words were: "You negotiated a settlement because you could not afford, emotionally or financially, a long, costly, and uncertain litigation."

On my lawyer's advice, I wrote out a list of furniture, china, and linens from my former home, items I considered to be my personal property. I was scrupulously careful not to include anything I hadn't paid for myself.

One evening a few weeks later when I returned from the theater, Anna wordlessly handed me a fistful of faxes that had come through, one after another.

In rapid, staccato succession, Philip demanded the return of everything he had given me during our years together. His list included the gold snake ring with the emerald head from Bulgari; $28,500 per annum he had given me over 12 years; $100,000 of his money used to buy bonds in my name; $10,000 for a "special travel fund"; $150 per hour for the "five or six hundred hours" he had spent going over scripts with me; a mirror he had bought to sit over the fireplace in my London house; a portable heater for the kitchen there; numerous books and records he had purchased; 40 percent of the sale money from my car, to which he had contributed 40 percent of the original cost; the stereo equipment from the house in London; half of the costs incurred on our holiday to Marrakech in 1978, for which I could expect the original receipts in due course; and "a little something" for adapting The Cherry Orchard and writing a play about the writer Jean Rhys; and last, for refusing to honor my prenuptial agreement, he levied a fine of $62 billion—a billion dollars for every year of my life.

At first the element of mockery I was doubtless intended to read into these messages was entirely lost on me. Anna and I sat there, both stunned into silence, as another fax began to grind its way out. Could it have been the ninth or the tenth that evening? The ludicrousness of this scenario started to dawn on us and we began to laugh like children.

It took four months before he saw fit to release some, though not all, of the items on my list. The machine-gun fusillade of that night had concluded with a final blast ordering me never to disturb him again—either by fax, telephone, or in person. By now I was only too happy to oblige, but Philip appeared to have overlooked the fact that he was the one initiating contact. Then, suddenly, communication between us ceased.

I learned the truth sometime after I had ceased to be a factor in Philip's life. He left me for a person I'll call Erda: a beautiful woman who had been a close friend to both of us for years. As the saying goes, the wife is the last to know.

Trusting and somewhat naive, Erda also found herself reluctantly playing a role in removing me from Philip's life. Her ambiguous position as friend to me and lover to him must have confused and disturbed her greatly. But once started, there was no easy way to halt the sequence of events: I moved out and Erda moved in.

For refusiig to honor my prenuptial agreement, he levied a fine of $62 billion-a billion for every year of my life.

Totally committed to this new relationship, Erda asked her husband of 25 years to give her a divorce. Confused, bitter, and distraught, he couldn't understand what had happened between them. It was only after the end of the relationship with Philip that she was able to confront him with the truth.

So far as I can gather, Philip and Erda's life together was, in the beginning, fulfilling to both. But soon some familiar patterns began to reassert themselves. With their increasing intimacy Philip's anxieties over being emotionally engulfed by a woman were galvanized, and he began to withdraw from her. Erda learned that he had been involved with a young woman when Philip and the young woman were both patients of Silver Hill Hospital. Shattered by his manipulation of her and his ultimate betrayal, Erda suffered a collapse. During this time, on the advice of her doctors, she found the strength to break off the relationship. She has embarked upon a new life with new surroundings—but the anger, hurt, and humiliation remain.

I spoke to Erda about her affair with Philip, setting aside my own ambivalent feelings toward a friend who had been so cruelly treated by my husband. Our meeting took place after the dust had settled on our misfortunes. She seems to echo my own experience: throughout the relationship, his pitilessly furious face terrified her; she was paralyzed by his invective; and there wasn't anything she wouldn't do to avoid a confrontation with him. Everything that had passed between my former husband and myself during the 18 years we lived together seemed to recur in the space of a few months between them. The process had simply accelerated.

As I listened to Erda tell her terrible story, the feelings of need and disappointment she expressed could easily have been my own.

I received an unexpected letter one day. It was from Philip, and contained the following message: "Dear Claire, can we be friends?"

I had awaited these words since our separation; regardless of the past, I knew I needed only to be patient and eventually the illness that had been the true cause of our parting would pass.

Replying to his letter, I wrote that there was nothing I desired more than to resume our friendship—it was up to him to state the terms and name the place where we should meet. Philip suggested a restaurant not far from my new home in New York, in one week's time. I spent the next seven days counting each hour, in a state of anxious anticipation.

The day before we met, I treated myself to a facial, a manicure; I picked a pretty outfit I had been saving for a special occasion. And now, here it was.

I caught sight of Philip before he saw me. His expression was grave and serious; he was wearing the same raincoat we had bought together in London many years before. He looked, I thought, somewhat apprehensive—but then, so was I. After a careful greeting, we sat down at our table.

Philip was considering me from behind glasses, sizing me up. After our coffees were ordered, there was a long silence. After they were delivered, I tried to conceal the tremor in my hand as I lifted the cup toward my mouth. He also appeared tense.

I was determined to be at my most charming and witty. I began the conversation by saying that it was good to see him—and so it was, despite all that had passed between us. Speaking calmly, Philip replied that he had expected me to be full of resentment. I assured him that a meeting would have been pointless if resentment was all I could feel. Goodnaturedly, we shook hands in agreement.

I noticed he was a trifle grayer than before, but otherwise looked much healthier than when I had last seen him. I wondered if there was a new woman in his life. There was another long pause. "You begin," I said.

For the next 20 minutes, nonstop, he performed for me a string of wisecracks and anecdotes, sharply funny as ever, completely impersonal, and unrelated to the friendship we were supposedly there to address and re-establish. Immobilized once again by another surprise tactic, I sat and listened, wondering how long this coffeehour tour de force could endure without something warm—or, actually, something relevant—being said.

I interrupted the flow and looked at him directly.

"Philip, why do you want to be friends with me?"

He looked back, and the suspicion of a smile crept across his lips.

"Oh, perversion ..."

Let down and deeply disappointed, I left the restaurant; I swore I would never again go through such an ordeal. Now begins the rest of my life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now